Home | Category: Aboriginals

ABORIGINALS OF AUSTRALIA

Aboriginal people have lived in Australia for over 50,000 years, making them the world’s longest-lasting, continuously surviving culture, according to the Australian government. They are not a single group but comprise hundreds of distinct nations, clans, and language groups with unique cultures and traditions. When Europeans began settling in Australia in 1788, it is estimated there were around 300,000 to one million of them. After this, Aboriginals struggled through a prolonged period of significant violence, disease, and dispossession that led to severe population declines and cultural disruption. Today, Aboriginal peoples continue to face significant health, social, and economic disparities compared to the non-Indigenous population.

Aboriginals have a very different background and culture than European Australians. Dreaming, a spiritual realm that connects people to their land, ancestors, and the creation of the world, is a central concept in their beliefs and religion. Traditionally, their stories, and knowledge have been passed down through generations via song, dance, art, and oral storytelling. They have traditionally lived in close contact with nature.

Aboriginal peoples have faced discrimination and marginalization under European Australians, including being excluded from the national population census until 1967. Tasmanian Aboriginals were essentially exterminated in the early 19th century. Many living Aboriginals resent the the way their ancestors were treated by European colonists in the past and continue to struggle for rights to their traditional lands and financial compensation for lost lands and resources. In February 2008, Prime Minister Kevin Rudd formally apologized to Aboriginal peoples for mistreatment by the Australian government in the past, singling out the "Stolen Generations" — Aboriginal children forcibly removed from their families to attend boarding schools where they were punished for speaking their native languages and following their native traditions. [Source: J. Williams, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life”, 2009, Encyclopedia.com]

Books: “The Australian Aborigines” by Kenneth Maddock; “Triumph of the Nomads” by Geoffrey Blainey; “Songlines” by Bruce Chatwin; “Loving Country” by Bruce Pascoe and Vicky Shukuroglou, is a travel guide to sacred Australia

RELATED ARTICLES:

EARLY MODERN HUMANS IN AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

LIFE OF EARLIEST HUMANS IN AUSTRALIA: TOOLS, WEAPONS, ART, SETTLEMENTS ioa.factsanddetails.com

PEOPLE WHO LIVED AUSTRALIA 20,000 TO 10,000 YEARS AGO ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

RITUAL LIFE AND MYTHS OF ANCIENT AUSTRALIANS ioa.factsanddetails.com

EARLY ABORIGINALS ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

VERY, VERY OLD AUSTRALIAN AND ABORIGINAL ROCK ART ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINALS AT THE TIME EUROPEAN COLONIZATION BEGAN ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL TASMANIANS: HISTORY, ABUSE, LIFESTYLE AND NEAR EXTINCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIA ABORIGINALS FROM 1900 TO PRESENT: DISCRIMINATION, ASSIMILATION, SOME RESTITUTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIA’S STOLEN GENERATIONS: VICTIMS, LAWS, RATIONALE, OUTRAGE ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL RELIGION: TRADITIONAL BELIEFS, DEMOGRAPHY AND DEATH ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL CUSTOMS, SOCIETY AND RITUALS ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL LIFE: WHERE THEY LIVE, WORK, DIET, HEALTH, ALCOHOL ioa.factsanddetails.com

TRADITIONAL ABORIGINAL LIFE: FOOD, HOMES, HUNTING ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL MEN AND WOMEN: GENDER, MARRIAGE, SEX ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIAN SEX: PRACTICES, ATTITUDES, ADOLESCENCE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIAN ART ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL PAINTINGS ioa.factsanddetails.com

MODERN AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL ART: PAPUNYA, MANGKAJA, REDISCOVERY, REVIVAL, AND A NEW AUDIENCE ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL ART FROM DIFFERENT REGIONS ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL ART OF NORTHERN AUSTRALIA: ANCIENT ROCK ART AND BARK PAINTINGS ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL ART FROM QUEENSLAND AND THE TORRES STRAIT ioa.factsanddetails.com

WELL-KNOWN ABORIGINAL ARTISTS: THEIR LIVES, WORKS AND IMPACTS ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS IN QUEENSLAND: SOME GROUPS, CUSTOMS, LIFESTYLES ioa.factsanddetails.com

WIK MUNGKAN PEOPLE OF NORTHERN QUEENSLAND: HISTORY, CUSTOMS, LIFE ioa.factsanddetails.com

TORRES STRAIT ISLANDERS: HISTORY, TRADITIONAL LIFE, CULTURE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIANS IN NORTH NORTHERN TERRITORY: SOME GROUPS, CUSTOMS, LIFESTYLE ioa.factsanddetails.com

YOLNGU OF ARNHEM LAND: HISTORY, MUSIC, TRADITIONAL LIFE, CUSTOMS ioa.factsanddetails.com

TIWI PEOPLE OF NORTHERN AUSTRALIA: HISTORY, CUSTOMS, TRADITIONAL LIFE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS OF CENTRAL AUSTRALIA: SOME GROUPS, CUSTOMS, ART, LIFESTYLE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ARRERNTE (ARANDA) PEOPLE: HISTORY, LANGUAGE, TRADITIONAL LIFE, CUSTOMS ioa.factsanddetails.com

WARLPIRI OF THE CENTRAL AUSTRALIAN DESERT: HISTORY, TRADITIONAL LIFE, CUSTOMS ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS IN WESTERN AUSTRALIA: SOME GROUPS, HISTORY, CUSTOMS, TRADITIONAL LIFE ioa.factsanddetails.com

MARTU OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA: HISTORY, CUSTOMS, TRADITIONAL LIFE ioa.factsanddetails.com

NGAATJATJARRA PEOPLE OF WEST-CENTRAL AUSTRALIA: HISTORY, CUSTOMS, TRADITIONAL LIFE ioa.factsanddetails.com

PINTUPI OF AUSTRALIA’S WESTERN DESERT: HISTORY, CUSTOMS, TRADITIONAL LIFE ioa.factsanddetails.com

Aboriginal Names and Identity

Indigenous people in Australia are technically referred to as Aboriginal people and Torres Strait Islanders. Aboriginal people are related to those who already inhabited mainland Australia when Britain began colonizing the island in 1788. The Torres Strait Islander communities come from people who lived on the Torres Strait Islands. These islands are part of Queensland, Australia, which took control of them in 1879. However, within these two broad identities, there are many other specific groups. Legally, “Aboriginal Australian” is recognized as “a person of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander descent who identifies as an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander and is accepted as such by the community in which he [or she] lives.” [Source: Erin Blakemore, National Geographic, January 31, 2019]

Aboriginal means "indigenous." Aboriginal people prefer to be called by their specific nation or community name, such as Koori or Nunga, rather than the generic terms 'Aboriginal'. The term “Aborigines” was used in the past but today it is sort of the equivalent a calling a black American a negro. Aborigines is not necessarily a derogatory term. Like negro and colored with African-Americans, it is more that it was used at a time when discrimination against indigenous Australians was more common place and accepted. While the term 'Aboriginal' can be used as an adjective (e.g., 'Aboriginal woman'), it is not appropriate as a noun. To refer to both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, use 'Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples' or 'First Nations people'. Always prioritize the individual's or group's preference.

The names Aboriginals call themselves are often names from their own languages, such as Koori in the east and south (meaning ‘Our People’), Nyunga or Noongar in Western Australia, Yolngu in the Northern Territory, Anangu in central Australia and Nungga in South Australia. Aboriginal identity is complex, and often defined by notions of family, extended ‘skin’ (clan groups), language groups, and by the ‘Nation’ and ‘Country’ — territory or area of land — where an individual hail from or is living at the time. The names Aboriginal use for themselves are not used so much by white Australians, and even less outside of Australia. [Source: Ilsa Sharp, “CultureShock! A Survival Guide to Customs and Etiquette: Australia”, Marshall Cavendish, 2009]

Aboriginal Population and Where They Live

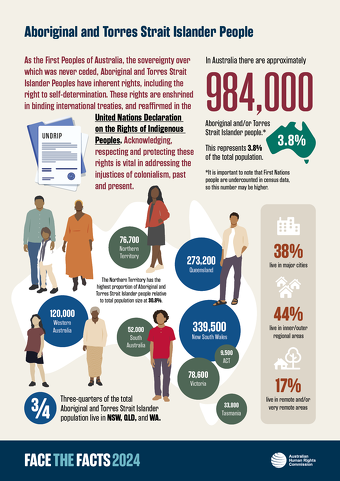

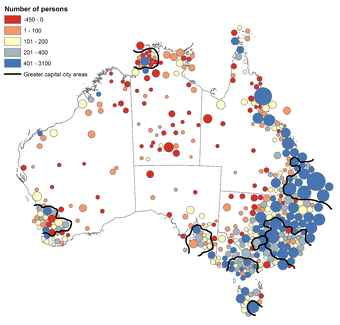

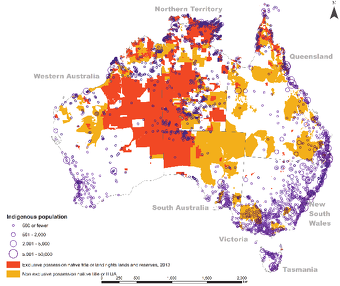

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people make up 3.2 to 3.8 percent of Australia's population of 26 million. Estimates by the Australian Bureau of Statistics indicate their population had surpassed 1 million people as of 2025. A significant proportion of the population lives in New South Wales, Queensland, and Western Australia, with the Northern Territory having the highest proportion of Indigenous people in relation to its total population. Approximately a quarter of the total population of the Northern Territory is Aboriginal according to the 2021 Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Census. This is the highest percentage of any Australian state or territory. They made up about a third according to the 2006 Australian Census of Population and Housing. Only about 260,000 people live in the Northern Territory. [Source: The Australian, Google AI].

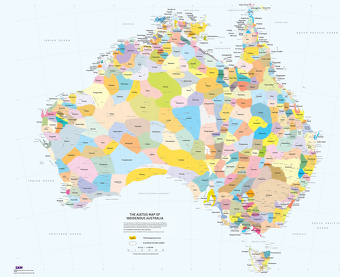

Distribution of Indigenous population in Australia, and exclusive native title and land rights, or non-exclusive native title or Indigenous Land Use Agreements, 2013, from Researchgate

Changes in the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) counts between censuses are not solely due to demographics. Increased participation and greater response rates to the Census question on Indigenous status have also contributed to higher counts. The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population is projected to grow, reaching between 1,171,700 and 1,193,600 by 2031. The Aboriginal population has a younger age structure than the non-Indigenous population, with 33.1 percent under the age of 15.

Australian Aborigines traditionally lived throughout Australia and Tasmania, with each cultural group adapting to the regioon where they lived. In the central and western desert regions, Aboriginal groups traditionally were nomadic hunters and gatherers. They had no permanent place of residence, although they did have territories, and ate whatever they could catch, kill, or dig out of the ground. The Australian desert is an extremely harsh environment with hot days and cool nights and few permanent water sources. In the southern parts of Australia, the climate is cooler and can be cold in the winter and thus the Aboriginal groups that lived there traditionally were more likely to live in permanent dwellings. Those living in northeast Queensland adapted the rainforests and marine environment there.

The majority of Aboriginals are scattered across the continent in small towns and settlements, with large concentrations in the urban areas of Alice Springs, Darwin, Broome and the Redfern suburb of Sydney. Although Aboriginals are a minority is Australia as a whole they are a majority in man interior regions. They are concentrated in central and northern Aboriginal. They make up about a quarter of the inhabitants of the Northern Territory. In suburban areas, and among young people, there has been some mixing of Aboriginals and whites and other ethnic groups.

Fall and Rise of the Aboriginal Population

Soon after the European conquest of the Australia continent in the 18th century, the Aboriginal population began declining rapidly as a result of violence and disease. Aboriginals are thought to have numbered one million when the Europeans arrived in 1788, maybe more as no one really knows what their numbers were. By 1888 the population had fallen to as low as 60,000 while that of Europeans had risen to over one million. Imported diseases such as smallpox were particularly devastating to Aboriginals, but violence also took its toll. [Source: Ilsa Sharp, “CultureShock! A Survival Guide to Customs and Etiquette: Australia”, Marshall Cavendish, 2009 ^^]

For the most part population numbers for Aboriginals during much of their history are sketchy because they were considered non-persons and not counted in censuses until 1967. In his book “Secret Country, the Aboriginals” John Pilger wrote that Aboriginal were considered “part of the fauna” rather than humans.

In the 1980s, Aboriginals made up about 1.6 percent of the Australia population, numbering around 386,000 individuals. According to the 1996 census, there were 352,970 Aboriginals in Australia, a 33 percent increase from 1991. At that time doing an accurate count of Aboriginals was difficult because many of them lived in remote areas and some did not cooperate with census takers. In the 2000s there were between 400,000 and 500,000 Aboriginals (between two and three percent of the population) living in Australia. According to a 2020 study published in the journal Population, Space and Place, their population rose from 517,000 to 798,000 between 2006 and 2016.

The rising trend over recent years is in part due to improvement in the treatment and lifestyles of Aboriginal Australians, and to a higher than average birth rate, but partly also to the increasing acceptability of declaring publicly one’s aboriginality, even in the case of mixed-bloods. In the old days, mixed-bloods — ‘half-castes’ as they were called then — were barred by law from claiming Aboriginal ancestry. ^^

Aboriginals, Race and Physical Differences

Most anthropologists no longer regard race as a valid concept. Old anthropology textbooks defined five major races: "whites," "African blacks," "Mongoloids," "aboriginal Australians," and "Khoisans." These in turn were divided into various number of sub-races. Indigenous Americans (American Indians) fell into the Mongoloid category.

The curly hair, blue-black skins, spread noses and thick lips of Australia Aboriginals are reminiscent of the peoples of southern India, New Guinea and Melanesia (Solomon Islands, Vanuatu and islands in the western Pacific). Hair color varies strikingly among Europeans and native aborigines. Groups with a predominance of "loops" in the fingerprint patterns include most Europeans, black Africans and east Asians, while groups with mostly "whorls" include Mongolian and Australians aborigines. Groups with "arches" include Khoisians and some central Europeans."

Almost all aboriginals are lactase deficient. This means they traditionally had problems digesting milk products. Lactase positive races, groups of people that can easily digest milk in adulthood because of the presence of the enzyme lactase, include northern and central Europeans, Arabians and some West African groups such as the Fulani.Lactase negative races include east Asians, other African blacks, American Indians, southern Europeans and Australian aborigines. .

Around 8000 years ago most people were lactase negative, because they stopped drinking when their were weaned form their mothers. Beginning around 4000 B.C. some groups of people began drinking milk from domesticated animals and later milk became an important food source an for people in northern and central Europe, Arabia and parts of West Africa. Natural selection enabled these people to retain the lactase enzyme into adulthood while groups that drink milk lost the enzyme in childhood. Today, even many Lactase negative individuals can consume milk products.

Despite these differences, the important thing to realize, according to population geneticist Luca Cavalili-Sforza, author of “The History and Geography of Human Genes”, is once surface traits such as skin color and body shape are discounted, human races are remarkable alike. The differences between individuals within a race are much greater than the difference between races. Cavalli-Sforza argues the diversity among individuals is "so enormous that the whole concept of race becomes meaningless at a genetic level.” [Source: Sribala Subramanian, Time magazine, January 16, 1995]

One interesting finding in Cavalli-Sforza's book is the difference between Australian Aboriginals and black Africans. Based on superficial traits such as skin color and facial features you would think that the two groups are closely related. But according to Cavalli-Sforza, of all the racial groups in the world, Aborigines and Africans, on a genetic level, are perhaps the most different. Africans are more closely related to Europeans and Aborigines are more closely related to South Asians, than Africans and Aboriginals are related to each other.

Poor State of Affairs for Australia’s Aboriginals

Sarah Newey wrote in The Telegraph: Since 1788, when Captain Cook “first stepped foot on the continent, Indigenous people have been massacred, seen their children taken in a “stolen generation”, and resettled in tightly-controlled ‘missions’ and reserves where their culture and language was suppressed. These assimilation policies only ended in the late 1960s – it was not until 1971 that Aboriginal Australians were even counted in the census. This legacy, said Mr Si is seen today in the inequalities still facing many Indigenous communities. [Source: Sarah Newey, The Telegraph, October 12, 2023]

On average, Aboriginal people live eight years less than their non-Indigenous counterparts and are nine times more likely to be homeless. Incarceration rates remain 14 times greater. In remote communities in the dusty Northern Territory, roads are unpaved, many houses are crumbling, and “third world” illnesses like rheumatic heart disease remain common. In inner city Sydney, gentrification is pricing some Indigenous people out of their neighbourhoods, while overcrowding and unemployment remain significant challenges.

Some previous attempts to reverse negative trends have been heavy-handed – with events in Alice Springs, a dusty, remote town in the heart of Northern Territory where around 20 per cent of people are Aboriginal, perhaps the most infamous example. In 2007, in a policy known as “the intervention”, the local army was deployed, limits on alcohol purchases introduced, and racial discrimination laws and property rights suspended.This “emergency response” aimed to tackle disproportionately high rates of domestic violence, crime, and allegations of child abuse, mostly in camps dotted around the desert town which were set up by Aboriginal people displaced from their traditional lands.

The approach, which also saw welfare budgets squeezed, was criticised by the UN in 2017, which urged that “policies be made with communities – rather than to communities”. “The intervention tore down all the progress we’d made building leadership in that community,” says Tom Slockee, chair of the Searms Community Housing Aboriginal Corporation. “There’s always been this view that other people know what’s best, how to fix our situation and improve our lives… Aboriginal people have been kept out of the decision-making process.”

Aboriginal Languages

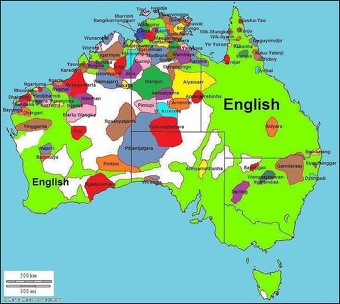

There were over 250 distinct Indigenous Australian languages and 800 dialects spoken in 1788 when Captain James Cook initiated the European colonization of Australia. At that time neighboring tribes usually spoke different dialects but sometimes they spoke completely different languages. Due to assimilation policies and dispossession, only about 120 to 150 are still spoken today, and most are considered endangered. Only about 18 Aboriginal languages, such as Walpiri, spoken in the Alice Springs area, are still widely spoken. Walpiri is taught in schools and a there is a fair amount of literature and media produced in the language. [Source: Google AI; J. Williams, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life”, 2009, Encyclopedia.com]

Aboriginal Australian languages are very different in structure from Indo-European languages such as English. Many have complex grammatical structures. Some have five future tenses. The Karajaara Aboriginal language has been described as having "a soft musical" quality that "sounds almost like Italian." The only use of clicks outside Africa is in Australian aboriginal initiation languages. According to The New Yorker, The Guugu Yimithirr language does not have words for individual-focused directions like “right, “left, “behind” and “in front of”. Instead they use the cardinal directions. They don’t kick a ball with their right or left legs but rather with their north and south legs. If they turn 90 degrees they use their east and west legs.

J. Williams Wrote in THE “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life”: Some Aboriginal languages encode gender grammatically through a system of noun classes. While somewhat similar to the use of gender in many Indo-European languages, the Aboriginal systems are more complex and have provided some interesting semantic relationships. For instance, in Dyirbal, which was once spoken in far northern Queensland, there were four noun classes. The first class included men and animate objects. The second class included women, water, fire, and violence; all of which were considered dangerous by the Dyirbal. The third class was composed of edible fruits and vegetables, while the fourth class included everything that was not in the first three classes. [Source: J. Williams, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life”, 2009, Encyclopedia.com]

Origin and History of Aboriginal Languages

Ten portraits of Aboriginal Australians: 1st row (right to left): 1) Windradyne, an Aboriginal warrior from the Wiradjurijpg, 2) David Gulpilil, 3) Albert Namatjira, 4) David Unaipon, 5) Mandawuy Yunupingu

2nd row (right to left): 1) Truganini, 2) Yagan, 3) Geoffrey Gurrumul Yunupingu, 4) Bennelong, 5) Robert Tudawali

Linguists believe that all of the languages of the Australian continent are related to each other; however, there is some disagreement about the their relationship with the language of the Tasmanians, which is now extinct. While most Aboriginal Australian languages evolved in isolation from outside influences, some cross-fertilization occurred in the Northern Territory and parts of northwestern Western Australia. Ancient trading links with Indonesian fishermen seeking Australia’s valuable sea slugs and trochus shells led to the adoption of Indonesian vocabulary in Aboriginal languages. In parts of the Northern Territory, the word for "foreigner" is balanda, which is Indonesian for "Dutchman" or "Hollander." [Source: Ilsa Sharp, “CultureShock! A Survival Guide to Customs and Etiquette: Australia”, Marshall Cavendish, 2009]

The largest language in terms of number of speakers is called the Western Desert language, spoken by several thousand Aboriginal people in the Western Desert region of the continent. Pitjantjatjara languages, which are Western Desert languages, are spoken in a wide area ranging from Kalgoorlie and Ceduna in Western Australia to the south and west, Ernabella and Musgrave Park in South Australia to the east, and Papunya and Areyonga in the Northern Territory to the north. Linguistic classifications currently accept Pitjantjatjara as part of the Wati subgroup of the Southwestern group of the Pama–Nyungan family, also called the Western Desert family. Most Pitjantjatjara language speakers are multilingual at the dialect level and often switch dialects when residing in new areas.

The Western Desert linguistic family shares many features with other Aboriginal Australian languages. With the exception of a group in northern Australia, linguists believe these languages are closely related and diverged from a single ancestral language within the last 10,000 years. However, the separation of these languages from their Asian antecedents occurred so long ago that no clear genetic connections have been detected with Asian languages today. [Source: Wikipedia, Richard A. Gould, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

The first full translation of the Christian Bible into an Aboriginal language — Kriol — was completed in 2007 after almost 30 years of work and was made available to about 30,000 Kriol speakers in the Northern Territories. [Source: ABC, May 5, 2007]

Aboriginal English and Words Derived from Aboriginal Languages

Most Aboriginal people speak English as their first or second language. In parts of Australia, distinctive kinds of English hav developed within Aboriginal communities. In the Northern Territory there is a kind of English spoken by Aboriginal people called Kriol. Kriol has developed since the arrival of Europeans. Originating in northern Australia and for a while described as the "native" language of young Aboriginals, it contains English words and Aboriginal words with Aboriginal grammar and pronunciation. Some Aboriginal English words and phrases include: 1) "Unna", a word meaning "true" or "ain't it?"; 2) "Sorry business", a reference to the cultural concept of expressing grief and respect for the deceased; and 3) "Welcome to country", a ceremony in which traditional owners give permission for others to be on their land.

Aboriginal words that have found their way into Australian English:

Billabong” — a waterhole

Boomerang — the curved Aboriginal hunting weapon that returns to its owner after hitting its target, using sophisticated aerodynamics

Corroboree — A festive gathering, a get-together, usually with music and dance

Humpy — an Aboriginal bark hut, originally a temporary dwelling erected by nomads, now used to describe any rough hut or shelter

Walkabout — the Aboriginal custom of taking a temporary migration from one’s home base, for an unplanned period of time and often without a specific goal in mind. The term is now used now of anyone who disappears mysteriously for a while to be alone or to escape something. ‘Can’t find Bill anywhere, musta gone walkabout.’”

Aboriginal languages have left their mark on white Australia, especially in place-names and in words for wildlife like kangaroo, wombat, dingo, kookaburra, budgerigar (budgie, the bird), barramundi (a fish). and koala. Among the Aboriginal-derived words for plants are mulga, coolibah, waratah and bangalow. Balanda is an Aboriginal word for whites.

Many of the Aboriginal words for animals were adopted early in Australia's history, especially from the Dharug language of the Sydney region. Non-Dharug words include jarrah, kylie, numbat, and quokka from the Perth area, and bunyip from the Geelong area. Many Australian place names of Aboriginal origin have suffixes like "-dah" or "-bah", which usually mean indicating "place of".

Endangered Aboriginal Languages

Aboriginal languages such as Dyirbal, Wanyi, Wakka Wakka and Kulilli are dying out at a rate of one every three years. By one estimate of the 145 language still spoken in the late 2000s, 110 were severely and critically endangered, meaning the languages were spoken by only small groups of people, mostly over 50 years old. [Source: Google AI; J. Williams, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life”, 2009, Encyclopedia.com]

About 90 percent of Aboriginal languages are near extinction. Many are spoken by less than a thousand speakers. Only about 20 are spoken regularly and are being passed to the next generation. By one count 138 of the 261 aboriginal languages spoken when Captain Cook arrived are extinct or nearly extinct.

As of 2010 there were less than 50 speakers of Banyjima and less than 10 still speaking Yinhawangka. Many disappeared or were diminished when Aboriginals were forbidden from using their own languages. AFP reported: The policy of removing Aboriginal children from their families to assimilate with white Australians, creating the “Stolen Generations,” devastated native languages and culture in the last century. In many cases, children were barred from speaking their mother tongue at school or in Christian missions.“Sometimes Aboriginal parents also thought that their language would hold their kids back, so they wouldn’t use it,” says Michael Walsh, an expert on indigenous languages. “Then there was a missing generation where the parents would still speak in their language with their own parents, but not with their kids,” he says.

Reviving Endangered Aboriginal Languages

Efforts are underway to revitalize and preserve these languages, with communities actively working to revive at least 31 of them. Studies have shown that learning native languages restores a sense of cultural identity to Aborigines, and improves their physical and mental health and academic performance. [Source: Marie Le Moel, AFP, October 28, 2010]

According to AFP: Sydney University’s Koori Centre is at the forefront of efforts to reverse the tide, along with initiatives like Waabiny Time, a national Aboriginal TV program with simple language lessons for children. In New South Wales, the most populous state, 5,000 children learn an Aboriginal language at school, while there are similar courses in Aboriginal language and culture in South Australia and Victoria.

There have even been examples where a language thought to have completely disappeared has been revived, like Kaurna, in South Australia. “The last time it was spoken daily was in the 1860s,” says Robert Amery, linguist at Adelaide University.

Working from a few old documents, the community, along with indigenous language experts, has found a renewed interest in its language. Now, it is used in ceremonies and political speeches, and the Kaurna people are -creating new expressions adapted to modern society. “There are workshops to develop new words, for instance expressions parents need with their kids,” Amery says. “‘Nappy’ [diaper] has been translated to wornubalta, from wornu which means ‘bum’ and balta for ‘covering,’Similarly, some words have been created for telephone, -television and computer,” he says.

However, Walsh says language is often not a priority for Aboriginal people, who have a relatively low life expectancy and are affected by widespread alcoholism and high unemployment, “A language can be revived. But it depends on the will of the community and the availability of linguists. Some communities are so divided they are only focused on survival: Language isn’t their priority,” Walsh says.

However, the recent recognition of indigenous languages has had a major impact. “Schools which offer -Aboriginal languages programs are recognizing and valuing those languages and cultures,” says Susan Poetsch, who trains Aboriginal teachers at Sydney University. “This increases the esteem and pride of Aboriginal students, and it has a positive impact on their attendance and participation in school. Some research indicates that it improves their physical and mental health. People who have lost their identity are quite conflicted. In regaining their language, they start to become more functional in the community. It turns their life around.”

However, other experts are less optimistic. In the Northern Territory, the only place where bilingual schools exist, a change has occurred recently. From now on, these schools will begin each day in English. In some remote Aboriginal schools, kids may not attend for much more than four hours, so making the first four hours only in English effectively prevents a bilingual program from operating,” Koori Centre linguist John Hobson says. “If they only hear and speak an Aboriginal language at home and only English at school, they are unlikely to acquire either successfully,” he says.

He says that while Aboriginal languages are still spoken fluently in some parts of northern and western Australia, that is far from the case in urban areas. “The initiatives we currently have in schools are good. But if the aim is to produce fluent speakers who speak an Aboriginal language in their daily lives, it is not enough,” Hobson says. “We need regional, state-wide and national plans. There are huge advantages to developing bilingualism in kids. But Australia is obsessively monolingual.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated September 2025