Home | Category: Aboriginals / Arts, Culture, Media

REGIONAL AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL ART FROM DIFFERENT REGIONS

Different Aboriginal groups had and have their own means of artistic expression. They often have their own forms of art, their own images and subjects and styles. In urban areas, a large number of Aboriginal artists, influenced by both Western and Aboriginal art, are active. One of the most-well known members of this group is David Mpetyane.

Aboriginal art from the Kimberley region of western Australia is known best for its images of Wandjina, ancestral beings who came from the sky and usually depicted with a hallo. large eyes and nose but no mouth. The beings were often found in rock paintings in the area and are believed to have created many of the Dream Place natural features. Aboriginals around Broome create unique pearl shell pendants with various kinds of engravings.

So called dot-paintings are the most well-known forms of Aboriginal art to come out of central Australia. They are believed to have developed out of the "ground paintings" — paintings made on the ground during traditional ceremonies from pulped plant material in different colors dropped on the ground to make outline objects on rock paintings and highlight geographical features.

North Queensland features extraordinary rock art. Many feature the Quinkan spirits, which come in two forms: the crocodile-like Imjim with knobbed club-like tails; and 2) the stick-like Timara. Clubs, shields, boomerangs and woven baskets have been made with a wide variety of designs.

RELATED ARTICLES:

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIAN ART ioa.factsanddetails.com

VERY, VERY OLD AUSTRALIAN AND ABORIGINAL ROCK ART ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL PAINTINGS ioa.factsanddetails.com

MODERN AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL ART: PAPUNYA, MANGKAJA, REDISCOVERY, REVIVAL, AND A NEW AUDIENCE ioa.factsanddetails.com

WELL-KNOWN ABORIGINAL ARTISTS: THEIR LIVES, WORKS AND IMPACTS ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS (FIRST NATION PEOPLE) OF AUSTRALIA: NAMES, DEMOGRAPHICS, LANGUAGES ioa.factsanddetails.com

EARLY MODERN HUMANS IN AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

LIFE OF EARLIEST HUMANS IN AUSTRALIA: TOOLS, WEAPONS, ART, SETTLEMENTS ioa.factsanddetails.com

PEOPLE WHO LIVED AUSTRALIA 20,000 TO 10,000 YEARS AGO ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

RITUAL LIFE AND MYTHS OF ANCIENT AUSTRALIANS ioa.factsanddetails.com

EARLY ABORIGINALS ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINALS AT THE TIME EUROPEAN COLONIZATION BEGAN ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIA ABORIGINALS FROM 1900 TO PRESENT: DISCRIMINATION, ASSIMILATION, SOME RESTITUTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIA’S STOLEN GENERATIONS: VICTIMS, LAWS, RATIONALE, OUTRAGE ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL RELIGION: TRADITIONAL BELIEFS, DEMOGRAPHY AND DEATH ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL CUSTOMS, SOCIETY AND RITUALS ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL LIFE: WHERE THEY LIVE, WORK, DIET, HEALTH, ALCOHOL ioa.factsanddetails.com

TRADITIONAL ABORIGINAL LIFE: FOOD, HOMES, HUNTING ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL MEN AND WOMEN: GENDER, MARRIAGE, SEX ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIAN SEX: PRACTICES, ATTITUDES, ADOLESCENCE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS IN QUEENSLAND: SOME GROUPS, CUSTOMS, LIFESTYLES ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIANS IN NORTH NORTHERN TERRITORY: SOME GROUPS, CUSTOMS, LIFESTYLE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS OF CENTRAL AUSTRALIA: SOME GROUPS, CUSTOMS, ART, LIFESTYLE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS IN WESTERN AUSTRALIA: SOME GROUPS, HISTORY, CUSTOMS, TRADITIONAL LIFE ioa.factsanddetails.com

Art from Central Australia

The Arrernte Aboriginals of Central Australia carve sacred emblems called “tjurungas”. In the dreamtime each “tjurngas” was associated with a particular totemic ancestor and its spirit lived within it. When the spirit entered a women it was reincarnated as a child. Each person has his or her own “tjurngas”. Traditional Artistic expression, largely though not exclusively tied to ritual contexts, encompasses body decoration, ground paintings and carved sacred boards. Common materials include feathers and down and, pigments in red, yellow, black, and white. In the 1930s, many Western Arrernte artists successfully adopted watercolor painting, a tradition that continues today.

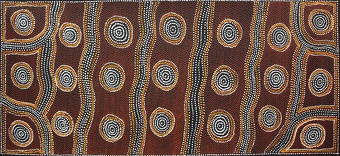

dot painting Japingka Gallery

Women from Utopia, 140 miles northeast of Alice Springs, are famous for producing batiks with designs based on images traditionally painted on women’s bodies. The same images are also painted on canvases with acrylic paints. The Dieri people living on the Killalpaninnna Luther Mission near Lake Eyre in South Australia produce distinctive wooden carvings. Many feature figures of possums, goannas and snakes that come in variety of sizes and have designs burned on them with hot fencing wire. The Pitjantjatjara women in southeast Western Australia and northwest South Australia produce woolen item such as scarves, rugs, belts and traditional dilly bags (carry bags) with designs associated with women's law.

See Separate Article: MODERN AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL ART ioa.factsanddetails.com

Dot-Paintings From Central Australia

So called dot-paintings are the most well-known forms of Aboriginal art to come out of central Australia. They are believed to have developed out of the "ground paintings," paintings made on the ground during traditional ceremonies from pulped plant material in different colors dropped on the ground to male outline objects on rock painting and highlight geographical features.

Many of the dot paintings look abstract but to experienced observers they contain images that can be easily identified: the tracks of animals, people or birds; boomerangs; spears; digging sticks and coolamans (wooden carrying dish). The boomerangs and spears are often symbols of men and the digging sticks and coolamans are often symbols of women because these were tools associated with each sex.

The dot paintings are often representations of Dream Place landscapes with concentric circles representing the Dream Places. Although the symbols can often be identified their context and association with other symbols is often known only to the artist.

See Separate Articles: MODERN AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL ART ioa.factsanddetails.com ; : AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL PAINTINGS ioa.factsanddetails.com

Aboriginal Art from Northern Australia

Northern Australia is most famous for its rock paintings and bark paintings. Some of the rock art there may be 40,000 years old. The art from North Australia is more literal than art from Central Australia. It often contain images of people and animals whose meanings ar widely understood.

making a dot painting Japingka Gallery

For tens of thousands of years, Aboriginal peoples have used art to record and share their stories of creation, culture, and ceremony. Across the north of the Northern Territory, ocher paintings, rock carvings, weaving, wood sculptures, screen-printed textiles, bark paintings, and decorated ceremonial objects remain central forms of expression, showcased today in art centres, galleries, and national parks.

From the vivid palettes of Utopia artists, to the luminous watercolours of Albert Namatjira depicting the landscapes of Hermannsburg, to the distinctive X-ray animal paintings of the Top End, Aboriginal art embodies both purity and cultural depth. Without words or sound, it transcends language and dialect to communicate story and meaning, offering profound insight into Aboriginal culture and heritage.

Hollowed-out logs used in reburial ceremonials among the Aboriginals of Arnhem Land were often elaborately decorated. The Marramunga people of the Murchinson Range of Northern Territory make ground painting of the great snake Wollonqua, who the Marramunga say was so enormous he could travel far and wide while his tail remained in the waterhole from which it originated.

Aboriginal Art from Western Australia

Aboriginal art from Western Australia is very diverse, ranging from ancient rock engravings in the Pilbara region to modern ocher-based artworks and acrylic paintings from the Kimberley and desert areas. Key artistic traditions include cave and rock paintings with hand stencils and depictions of ancestral beings, as well as ocher art from the Kimberley, which uses thick, natural pigments to create a distinct texture.

Kimberley is known for its unique Ocher Art, where artworks are created using natural ocher pigments from the land, resulting in a thick, crusty, and rough finish. Key sites include rock art near Kununurra and the petroglyphs of the Murujuga (Burrup Peninsula). The Golden Outback: is to ancient rock art sites like Walga Rock and Mulka's Cave, featuring ancient hand stencils, depictions of ships, and illustrations of Dreamtime stories and ancestral spirits.

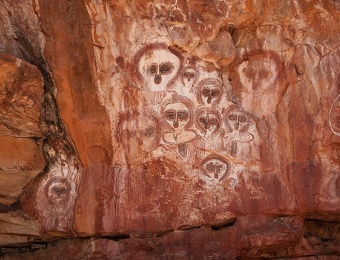

Ancient Aboriginal rock art with what appears to be early Wandjina on the Barnett River, Mount Elizabeth Station in Western Australia's Kimberley region

Central and Western Desert: Features vibrant acrylic paintings, often incorporating the well-known "dot painting" style. Many feature: 1) Dreamtime Stories about the creation of natural wonders, and the spiritual connection to the land; 2) Wandjina Ancestral Beings, with their large, haloed heads, represent ancestral spirits and rain-makers; 3) Native Fauna and Flora, some now extinct, and significant plants; and 4) Hand Stencils, a common technique where a hand is pressed to a rock and pigment is blown over it, creating a negative impression.

Aboriginal art from the Kimberley region of western Australia is known best for its images of Wandjina, ancestral beings who came from the sky and usually depicted with a hallo. large eyes and nose but no mouth. The beings were often found in rock paintings in the area and are believed to have created many of the Dream Place natural features.

The stories, motifs, and styles of Aboriginal art are often unique to specific language and community groups who hold cultural ownership. The Art also serves as a visual representation of Country and the ancestral stories embedded within it. Contemporary artists often use their work as a form of truth-telling, sharing cultural stories and highlighting the ongoing significance of their communities and traditions.

Western Australia is also well-known for it Aboriginal crafts, art objects and ancient Aboriginal artifacts. The Metropolitan Museum of Art collection contain several spear throwers from Western Australia. One dates to early to mid-20th century and is from the Kalumburu Mission. It is made of wood, paint, cockatoo feathers and human hair and is 74 centimeters (29 inches) long. Another spear thrower, from the Western Desert, dates to mid-19th–early 20th century. It is made of wood, spinifex resin, sinew, ocher and measures 13.3 x 67.3 centimeters (5.25 inches high, with a width of 26.5 inches). [Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art]

Engraved Pearl Shell Pendants from Northwest Australia

Aboriginals around Broome and in the Western Kimberley create unique pearl shell pendants with various kinds of engravings. The Metropolitan Museum of Art collection contains an engraved pearl shell and hair-string belt (riji, or jakoli, longkalongka) made pearl shell, human hair, ocher from the Western Kimberley. Dating to the late 19th–early 20th century measures 50.8 × 12.5 × 3.5 centimeters (20 x 4.9 x1.4 inches) [Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art]

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: Pearl shell was the highly prized focus of ritual and exchange networks in Australia. Its glistening iridescent qualities embody the shimmer of water, rain, and lightning, evoking ideas of spiritual well-being and ancestral connection. Engraved pearl shell pendants were given to boys during rites that marked their transition to adulthood and were predominantly used and worn by men during ceremonies, attached by belts or necklaces of hair string, with the power to bring rain or heal the sick. Known by a variety of local names (including riji, jakuli, longkalongka) they were, and in many areas still are, exchanged along a vast network of overland trade routes that extends along the western coast and across the vast desert interior as far as Australia’s southern shore, more than a thousand miles away.

Carved from the shell of the gold-lipped pearl oyster (Pinctada maxima), each is engraved with a series of angular geometric motifs which are filled with red ocher and fat, or powdered charcoal to highlight dynamic designs. These linear elements meander across the surface of the lustrous inner lip of the shell and are typically composed of three parallel lines which flow and interlock to create animated designs. The geometry of these interlocking zig-zags and meandering lines indicate the movement of water, so vital to life, in its many manifestations: the rain of storm clouds, the ebb and flow of tides, and the tracks of ancestral beings such as the Lightning Snake across the landscape.

Boomerangs

Boomerangs were not only useful tools and hunting weapons they could also be works of art. Eric Kjellgren wrote: An iconic symbol of Aboriginal culture and, more broadly of Australia as a whole, the boomerang is the most familiar and widely known of all Aboriginal art forms. Although not used in all areas, boomerangs of various types were created by Aboriginal peoples on most of the continent and served a variety of purposes. The most famous type are the "returning" boomerangs, which were made in parts of southeastern and western Australia. Used primarily for entertainment, returning boomerangs, when thrown outward, circle back to land near or to be caught by the thrower. In certain areas returning boomerangs were reportedly used in hunting wildfowl although some authors state this was not the case. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

The vast majority of boomerangs, however, were non-returning. Effective at a range of more than one hundred meters, boomerangs were essential, highly specialized throwing sticks, intended to strike the target and fall to the ground. In former times, boomerangs were employed primarily in hunting and warfare. Hurled from a distance with great force, boomerangs typically served to stun or otherwise incapacitate prey such as kangaroos or emus, allowing the hunter to catch up to the animal, which was killed with spears or other weapons.

In some areas boomerangs were used both as projectiles and as general purpose implements, serving, as needed, as knives, hammers, digging sticks, or fire-making implements. Some forms were, and continue to be, used as musical instruments, clapped together to provide rhythmical accompaniment to song and dance performances. In some places large boomerangs up to four feet long, never intended to be thrown, were employed as hand held weapons when fighting at close quarters.

One work in the Metropolitan Museum of Art collection is 55.6 centimeters (21 inches) long and is dated to the mid- to late 19th century. It has broad body and sharp pointed tips. It shows the classic form of fighting boomerangs from the western Kimberley region. As in most boomerangs, its subtle curve follows the natural grain of the wood — a design feature that imparted added strength to the implement.

Among the most ornate of Aboriginal boomerangs, western Kimberley examples are frequently adorned, with incised geometric patterns and occasionally with human or animal figures. Accented with red ocher, the delicate herringbone pattern on the present work may have been purely decorative. Some er, geometric patterns in Aboriginal art often carry deeper meanings; designs and motifs may allude to ritual art forms or to aspects and activities of the ancestral beings who formed the features of the landscape during the Dreaming. Another boomerang from the Metropolitan Museum of Art collection, from Western Kimberley, dates to the mid to late 19th century, is made from Wood, ocher and measures 55.2 × 11.4 × 1 centimeters (21.75 inches long , with a width of 4.5 inches and a depth of 0.4 inches).

Lower Murray Aboriginal Art

The Murray River is north of Melbourne and east of Adelaide in New South Wales and Victoria. Aboriginal Art from the Lower Murray River area, particularly shields and weapons, is well known. A Parrying Shield in the Metropolitan Museum of Art collection from the Lower Murray River region that dates to the 19th century. It is made of Wood and is 85.4 centimeters (33.6 inches) tall.

Other parrying shields from the same area and time period were made of wood, pigment and measured 81.3 x 5.1 x 14 centimeters (32 inches high, with a width of two inches and a depth of 5.5 inches) and 79.1 × 5.1 × 10.8 centimeters (31.1 inches high with a width of 2 inches and a depth of 4.25 inches. [Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art]

Eric Kjellgren wrote: Artists in the southeastern region of Australia formerly created two distinct varieties of fighting shields, each of which was designed for a specific purpose. The first were relatively broad, pointed oval forms, which were used to protect the bearer from projectile weapons, such as spears, throwing clubs, and boomerangs, thrown by the enemy from a distance. The second type were narrow compact parrying shields, used to ward off blows from fighting clubs and other handheld weapons during close combat. Made from dense hardwood, southeastern Australian parrying shields were typically wedgeshaped in cross section; the widest side formed the front. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

The shields were of thick wood and thus able to withstand the heavy impact of an opponent's weapons. The form and ornamentation of this work are characteristic of parrying shields from the lower Murray River region, in South Australia, where they were known among the Yaraldi people as mulgani. Tthe incised designs were likely created using specialized engraving tools made from opossum teeth. The decoration of lower Murray River shields is frequently divided, as here, into panels separated by transverse bars or meandering diagonal lines.

In one work the dividing lines are adorned in a rich red ocher, which forms a pleasing contrast with the white background pattern, carved in bas-relief. The overall design scheme is symmetrical in conception but not in the execution of the precise details, imparting a lively movement to the composition. The basic design elements-diamond-shaped motifs, herringbone patterns, and undulating parallel lines-that combine to form the overall composition on the present work appear on shields throughout southeastern Australia. Although there is virtually no historical information on the significance of the patterns, the images on southeastern shields may have been emblematic designs associated with the owner's group affiliation and Dreamings.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art collection also contains a club from the Lower Murray River region dated to mid-19th–early 20th century. It is made of wood and measures 76.8 x 4.5 centimeters (30.25 x 1.75 inches). There is also a spear thrower form Lower Murray River region dated to mid-19th–early 20th century in the collection. It is made of wood and measures 6.1 x 81.9 centimeters (2.4 x 32.25 inches). In 2020, Christie’s on Paris auctioned a Bouclier shield from the Murray River, 122 centimeters (48 inches) in height with an estimate value of €35,000-50,000.

Aboriginal Art from Queensland

North Queensland features extraordinary rock art. Many feature the Quinkan spirits, which come in two forms: the crocodile-like Imjim with knobbed club-like tails; and 2) the stick-like Timara. Clubs, shields, boomerangs and woven baskets have been made with a wide variety of designs.

There are also a number of Aboriginal art objects from Queensland in museums such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, including a mid to late 19th century spear thrower, made of wood, shell, resin and paint, from Aurukun on Cape York. It measures 89.2 x 8.9 x 2.2 centimeters (35.1 x 3.5 x D. 0.9 inches)

A shield, dating to the late 19th–early 20th century, form Central Queensland is made from wood, paint and is 9 3/4 inches high, with a width of 25 5/8 inches (24.8 x 65.1 centimeters). With its strongly convex surface, oval form, and brightly painted designs, this shield is likely from western Queensland. Carved from soft, light-weight wood, it served to ward off weapons, such as clubs, spears, or boomerangs, wielded or thrown by an opponent during fighting. Shields in western Queensland were decorated using a variety of techniques. Some examples were adorned with engraved designs, others were painted, and some were decorated using a combination of the two techniques. The present work is painted with a bold, hourglass-shaped motif in red, white, and black pigments. Although a number of motifs appear repeatedly on shields from this region, there is no historic information on the significance of the individual designs. [Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art]

The Metropolitan Museum of Art collection also contain a basket (Jawun) made by Northern Queensland people in the late 19th–early 20th century. According to the museum: The unique bicornual ("two-horned") baskets known as jawun produced by the rainforest peoples of northeastern Queensland in Australia are among the most elegant and versatile baskets in Oceania. Created only in the comparatively small region that lies between the modern settlements of Cooktown in the north and Cardwell in the south, jawun were used for collecting and processing food and, in the case of larger examples, at times for carrying young infants.

See Separate Article: AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL ART FROM QUEENSLAND AND THE TORRES STRAIT ioa.factsanddetails.com

Turtle Shell Masks of the Torres Strait

Eric Kjellgren wrote: The unique turtle-shell masks created by artists on the Torres Stra it Islands, which lie between the Cape York Peninsula of Australia and the southern coast of New Guinea, are among the most renowned of all Oceanic art forms. The masks were fashioned using a distinctive construction technique in which individual plates of turtle shell, heated by the mask maker and bent to the desired shape, were pierced with holes along the outer margins and then stitched together to create complex three-dimensional images. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

Once assembled, the masks were completed by the addition of hair, shell, feathers, nuts, and, occasionally, carved wood elements. The creation of masks and effigies from turtle shell was a centuries-old tradition; the earliest Western witness, in 1606, was the Spanish navigator Don Diego de Prado y Tovar, a member of the first European expedition to sail through the Torres Strait. Turtle-shell masks continued to be made until the end of the nineteenth century, when production and use largely ceased under the influence of Christian missionaries and colonial officials.

In recent years, however, some Torres Strait Islander artists have revived the tradition of mask making, including examples made from turtle shell. The forms and names of turtle-shell masks differed in the western and eastern islands of the region. In the west the masks were fantastic composite forms that combined the images or features of humans and animals. They were referred to generically as buk, krar, or kara, the latter two terms meaning "turtle shell." In the eastern islands the masks consisted almost exclusively of human images and were called le op, a term meaning "human face." Each individual mask also had a specific name, typically describing its purpose or the ceremony in which it featured. Although there is little precise information on the identity and function of individual examples, turtle-shell masks were used in similar contexts across the region.

See Separate Article: AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL ART FROM QUEENSLAND AND THE TORRES STRAIT ioa.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Culture Shock! Australia, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated October 2025