Home | Category: Aboriginals

PINTUPI

The Pintupi are an Australian Aboriginal group who are part of the Western Desert cultural group and speak a Pama-Nyungan language in the Western Desert Language Family. Their traditional land is in the area west of Lake Macdonald and Lake Mackay in Western Australia. They were hunters and gathers until relatively recently. Pintupi is not an indigenous term for a particular dialect nor for an autonomous community. The shared identity of these people derives not so much from linguistic or cultural practice but from a common experience and settlement during successive waves of eastward migrations out of their traditional homelands to the outskirts of White settlements.[Source: Nancy E. Gratton, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

The Pintupi population has not been precisely counted, but Joshua Project estimates a total of 1,400 Pintupi people in Australia, with a smaller group of 271 native Pintupi speakers reported in the 2021 census. Population figures for the Western Desert peoples as a whole are difficult to obtain. The sparsely populated Pintupi region, it has been estimated, can only support one person per 520 square kilometers, but given the highly mobile, flexible, and circumstance-dependent nature of the designation "Pintupi," absolute numbers are difficult to access.

The traditional territory of the Pintupi is located in the Gibson Desert in the Northern Territory of Australia. It is bordered by the Ehrenberg and Walter James ranges to the east and south, respectively; the plains west of Jupiter Wells to the west; and Lake Mackay to the north. The area is predominantly sandy desert interspersed with gravel plains and a few hills. The climate is arid; rainfall averages only 20 centimeters (8 inches) per year, and some years see no rainfall at all. Summer daytime temperatures reach about 50°C (122̊F), while nights are warm. Winter days are milder, but nights may be cold enough for frost to form. Water is scarce, and vegetation is limited. Desert dunes support spinifex and a few mulga trees. On the gravel plains, there are occasional stands of desert oaks. Faunal resources are also limited. Large game animals include kangaroos, emus, and wallabies, while smaller animals include feral cats and rabbits. Water only periodically appears on the ground after it rains. People rely on rock and claypan caches in the hills, as well as underground soakages and wells in the gravel pan and sandy dunes. ~

RELATED ARTICLES:

ABORIGINALS (FIRST NATION PEOPLE) OF AUSTRALIA: NAMES, DEMOGRAPHICS, LANGUAGES ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS IN WESTERN AUSTRALIA: SOME GROUPS, HISTORY, CUSTOMS, TRADITIONAL LIFE ioa.factsanddetails.com

MARTU OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA: HISTORY, CUSTOMS, TRADITIONAL LIFE ioa.factsanddetails.com

NGAATJATJARRA PEOPLE OF WEST-CENTRAL AUSTRALIA: HISTORY, CUSTOMS, TRADITIONAL LIFE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS OF CENTRAL AUSTRALIA: SOME GROUPS, CUSTOMS, ART, LIFESTYLE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIANS IN NORTH NORTHERN TERRITORY: SOME GROUPS, CUSTOMS, LIFESTYLE ioa.factsanddetails.com

EARLY MODERN HUMANS IN AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

LIFE OF EARLIEST HUMANS IN AUSTRALIA: TOOLS, WEAPONS, ART, SETTLEMENTS ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINALS AT THE TIME EUROPEAN COLONIZATION BEGAN ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIA ABORIGINALS FROM 1900 TO PRESENT: DISCRIMINATION, ASSIMILATION, SOME RESTITUTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIA’S STOLEN GENERATIONS: VICTIMS, LAWS, RATIONALE, OUTRAGE ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL RELIGION: TRADITIONAL BELIEFS, DEMOGRAPHY AND DEATH ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL CUSTOMS, SOCIETY AND RITUALS ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL LIFE: WHERE THEY LIVE, WORK, DIET, HEALTH, ALCOHOL ioa.factsanddetails.com

TRADITIONAL ABORIGINAL LIFE: FOOD, HOMES, HUNTING ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL MEN AND WOMEN: GENDER, MARRIAGE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIAN SEX: PRACTICES, ATTITUDES, ADOLESCENCE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIAN ART ioa.factsanddetails.com

Pintupi History

The Warratyi rock shelter near Pintupi traditional lands in the Western Desert region of Australia has been dated to 49,000 to 46,000 years ago. The Pintupi were among the last Western Desert peoples to come into sustained contact with Europeans. Until the early 1900s, their primary interactions were with neighboring Aboriginal groups of similar culture who lived in adjacent desert territories. As white settlements expanded around Pintupi country, the Pintupi began to migrate to their fringes, drawn by access to food and water during droughts. Initially, they camped separately from other migrants such as the Arrernte and Warlpiri, but as desert conditions worsened and populations increased, the government began establishing permanent camps. The Pintupi resisted integration into these larger settlements, seeking to maintain their own separate communities and minimizing participation in broader settlement affairs. [Source: Wikipedia; Nancy E. Gratton, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

Beginning in the 1940s, and continuing into the 1980s, the Pintupi moved — and in some cases were forced to move — into Aboriginal communities such as Papunya and Haasts Bluff in the Northern Territory. The Blue Streak missile tests of the 1960s accelerated this resettlement. Government officials, concerned that the missile trajectories might endanger groups still living traditionally in the desert, organized expeditions to locate and relocate them to settlements on the eastern fringe of the desert, including Haasts Bluff, Hermannsburg, and Papunya. As Pintupi families left the desert at different times and along different routes, they were dispersed across a range of communities at the desert’s edge, including Warburton, Kaltukatjara (Docker River), Balgo, and Mulan. The largest concentrations came to be at Kintore, Kiwirrkura, and Papunya. The last Pintupi group to abandon their traditional nomadic lifestyle was the so-called Pintupi Nine in 1984, whose “first contact” with outsiders was widely publicized and sensationalized in Australia (See Below).

During the 1960s, under the Menzies Liberal government, Pintupi were forcibly removed from their desert homelands to settlements closer to Alice Springs. Officially justified as preparation for assimilation into “modern society,” this policy involved relocation, suppression of Pintupi language and culture, and participation in the broader assimilationist practices that included the removal of Aboriginal children into institutions and foster care (the Stolen Generations). At Papunya, Pintupi became the largest language group, living alongside Warlpiri, Arrernte, Anmatyerre, and Luritja peoples.

Life in the settlements was marked by overcrowding, cultural disruption, and violence, both with white settlers and between Aboriginal groups. At Papunya, mortality was devastating: between 1962 and 1966, 129 people—nearly one-sixth of the population—died of preventable diseases such as hepatitis, meningitis, and encephalitis.

From the late 1970s onward, the Pintupi initiated a return to their traditional homelands in the Gibson Desert, a movement facilitated by the drilling of boreholes at outstations to secure permanent water supplies. This outstation movement led to the founding of new communities at Kintore (Walungurru) in the Northern Territory, Kiwirrkura in Western Australia, and Puntutjarrpa (Jupiter Well). The movement has contributed to both a demographic resurgence of the Pintupi and a revival in the use of the Pintupi language.

Pintupi Nine

The Pintupi Nine were a group of nine Pintupi people who lived a fully traditional, nomadic lifestyle in the Gibson Desert until 1984, when they made contact with relatives near Kiwirrkura in Western Australia. Unaware of European colonization and the profound transformations occurring elsewhere in Australia, they were widely referred to in the press as a “lost tribe” and hailed as “the last nomads” when they left their desert life in October 1984. [Source: Wikipedia]

The group consisted of two co-wives, Nanyanu and Papalanyanu, and their seven teenage children: four boys—Warlimpirrnga, Walala, Tamlik, and Piyiti—and three girls—Yalti, Yikultji, and Takariya. After the death of the father (husband of the two women), the family roamed between waterholes around Lake Mackay, on the Western Australia–Northern Territory border. They wore traditional hairstring belts and carried long wooden spears, spear-throwers, and intricately carved boomerangs. Their diet centered on goanna, rabbits, and native plant foods.

In the early 1980s, they began moving south after sighting smoke, believing it might signal nearby kin. They first encountered two campers from Kiwirrkura but fled after a misunderstanding involving a shotgun. The campers alerted community members, who quickly recognized that the family were Pintupi relatives who had remained in the desert when others moved to missions near Alice Springs two decades earlier. Vehicles were sent out, and the family was eventually located and persuaded to settle at Kiwirrkura. According to relatives, they were astonished to learn of food “coming out of pipes” and other aspects of settlement life. Medical examinations found them to be in excellent physical condition—lean, strong, and healthy.

After relocation, the family reunited with extended kin at Kiwirrkura and nearby Kintore. In 1986, one member, Piyiti, returned to the desert. Several of the others became prominent in the contemporary Aboriginal art world. The brothers Warlimpirrnga, Walala, and Tamlik (now known as Thomas) Tjapaltjarri achieved international recognition as the “Tjapaltjarri Brothers,” while the sisters Yalti, Yikultji, and Takariya became highly regarded painters in their own right. One of the mothers later died, while the surviving mother settled permanently in Kiwirrkura with her daughters. Although initially celebrated as the last hunter-gatherer nomads in Australia, their story was soon followed by reports of another small uncontacted group—the so-called Richter family—discovered in 1986 in the Great Victoria Desert.

Pintupi Religion

There are no firm figures for the number of Pintupi Christians, but estimates suggest between 700 and 1,200 Pintupi people are Christian, with sources like Joshua Project indicating that Christianity is a predominant religion within the group. The Pintupi people group is often grouped with the Luritja, and Joshua Project indicates that 50-100 percent of them are Christian, with many Evangelical Christians. [Source: Google AI}

Central to the traditional beliefs of the Pintupi people is the Dreaming (Tjukurrpa), which is the belief that the world was created and continues to be ordered. The Dreaming encompasses both the past and the present. Through the activities of the ancestral heroes, not only were the physical features of the world created, but also the social order according to which Pintupi life is conducted. Specific geological features of the terrain are believed to be the direct result of the deeds of these heroes. However, the Dreaming is also ongoing. It provides the force that animates and maintains life, as well as the rituals required to renew or enrich that force.[Source: Nancy E. Gratton, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

Religious authority lies primarily with patrilineage elders, whose accumulated knowledge of sacred traditions and totems qualifies them to instruct younger initiates. Ritual knowledge is not acquired all at once but unfolds gradually, as individuals are progressively led into deeper layers of ritual secrets over the course of their lives. Elders serve as both teachers and custodians, responsible for transmitting this knowledge to the next generation and for maintaining the sacred sites and the ancestral spirits associated with them.

Both men and women possess ritual knowledge linked to the Dreaming, expressed through ceremonies connected with initiation and the maintenance of sacred places. As among other Western Desert groups, large ceremonial gatherings are usually held when environmental conditions allow—for example, at waterholes following heavy rains. These events involve singing, chanting, and dramatic reenactments of ancestral myths, performed according to the demands of the particular occasion.

Death and Afterlife: Death initiates a complex cycle of mourning practices centered on the grief of the deceased’s kin. The place of death is abandoned, while the personal belongings of the deceased are distributed to more distant relatives whose grief is presumed to be less intense. Immediate kin often engage in self-inflicted wounds as an expression of sorrow, and “sorry fights”—ritualized attacks by the bereaved on the deceased’s coresidents for failing to prevent the death—are not uncommon. Interment is typically carried out by more distant relatives, as close kin are considered too overwhelmed by grief to undertake the task. The spirit of the deceased is believed to linger near the place of first burial until a secondary ceremony, held months later, allows it to depart. Beyond this point, the spirit is thought to travel to an unspecified realm “up in the sky.”

Pintupi Marriage and Family

The basic Pintupi domestic unit consists of a man, his wife or wives, and their children, though it often includes additional dependents such as an elderly parent of either spouse or a widowed sibling. First marriages are usually arranged by parents rather than based on the preferences of the prospective spouses. A young man approaching marriageable age will typically begin traveling with the camp of his prospective in-laws, contributing his hunting to their subsistence. After marriage, the husband resides with the wife’s parents until the birth of their first child or children. During this period, the wife begins instruction in her domestic responsibilities as well as in women’s ritual knowledge. Once children are born, the couple generally establishes their own independent camp. Polygyny is a common feature of Pintupi marriage. [Source: Nancy E. Gratton, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

In early childhood, caregiving falls primarily to the mother but is shared with cowives and other female kin in the camp. Young children are treated with considerable indulgence, yet from an early age they are taught the central values of sharing and cooperation. Both boys and girls enjoy wide personal freedom during childhood. For boys, initiation marks the beginning of the transition to manhood: this involves circumcision, instruction in ritual knowledge, and a subsequent period of extensive travel. During this time, young men develop wider social connections and gain exposure to diverse ritual traditions. For girls, deeper instruction in women’s ritual knowledge—“women’s business”—commences only after marriage and does not involve a comparable period of travel.

Among the Pintupi, the primary form of inheritance is not material property but ritual association with Dreaming sites. These associations, which imply both spiritual responsibilities and rights to resource use within the related territory, are passed down patrilineally. Portable personal property is minimal, and its distribution after death follows no rigid prescriptions, except that such items are given to more distant kin. This practice reflects the belief that close kin should not retain personal belongings of the deceased, since these might evoke excessive grief.

Pintupi Traditional Life, Culture and Economic Activity

Traditionally, the Pintupi were hunters and gatherers, subsisting on the diverse plant and animal resources of the desert environment. With the advent of government Aboriginal policies, many Pintupi who moved into settlements were employed as stockmen on cattle stations. Today, most Pintupi rely on government assistance payments, though some continue to supplement their income with hunting, gathering, and the production of art. [Source: Nancy E. Gratton, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

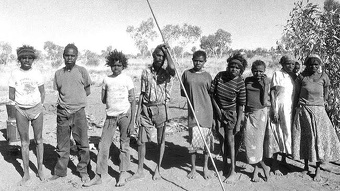

Pintupi elders in 1957

Traditional Pintupi life was highly mobile, with most encampments lasting only briefly, sometimes for a single night. Camps were typically organized by gender and marital status: unmarried men and youths lived together, single women formed a separate nearby camp, and each husband-wife pair with their young children maintained their own hearth. These camps were usually quite small, though larger gatherings took place at permanent waterholes following heavy rains. Shelter was simple, generally consisting of brush windbreaks, although in more recent times corrugated iron has been used. In contrast, the sedentary settlements established around boreholes may contain 300–350 residents, yet within these large settlements family and gender-based spatial arrangements still reflect traditional camp patterns.

Traditional tools and implements included digging sticks, stone-cutting tools, boomerangs, spears, and spear throwers. Shelters were formerly constructed from local materials but are now often made of canvas or corrugated iron. The majority of items produced in traditional life were utilitarian or ritual in nature, with ritual objects occupying a particularly important place. Traditional curing practices combined the use of herbal remedies with sorcery and ritual healing. Today, Pintupi communities also make use of Australian government health services, though traditional understandings of illness and healing persist.

Men primarily hunted large game—kangaroos, wallabies, and emus when available, and feral cats, rabbits, and small marsupials at other times. Women concentrated on gathering plant foods, grubs, honey ants, and lizards. Food was shared within the residential group according to kinship-based rules. Preparation of food was generally considered women’s work, though men were capable of it, just as men were primarily responsible for the manufacture and upkeep of hunting equipment, though women could also undertake such tasks when necessary.

Pintupi visual art, body adornment, song, and dance are integrally tied to the Dreaming. Each myth is associated with distinctive signs, chants, and ritual reenactments. In recent decades, Pintupi have also contributed to the Western Desert acrylic painting movement, producing artworks that have entered both national and international markets.

Pintupi Kin Groups and Land Tenure

The Pintupi recognize two endogamous patrilineal moieties — two divisions pertaining to marrying within a village or clan based on descent through the male line — which are crosscut by generational moieties, themselves consisting of eight paired (as wife-giving/wife-taking) patrilineal (based on descent through the male line) defined subsections. These distinctions of relatedness do not result in rigid groupings of individuals on the ground. Rather, they provide the terms according to which people may form connections with one another, request hospitality, or be initiated into Dreaming lore. [Source: Nancy E. Gratton, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

In regard to kinship terminology, the Pintupi initially differentiate according to subsection membership and further according to gender. Members of a single subsection are styled as siblings. However, within a subsection, the children of the "brothers" set are understood to belong to a different category than the children of the "sisters" set.

Rights to land refer to Dreamtime associations. That is, one has the right to live in and use the resources of areas to which one can trace family or friendship ties (the latter of which are most often treated in kinship terms). One's place of birth or the birthplaces of one's parents establish claims, but not to the land itself, only to rights of association with others who use that land.

Pintupi Social and Political Organization

The patrilineage (a social system where family membership, property, and status are traced exclusively through the male line of descent) is the largest unit of functional significance among the Pintupi. It plays a central role in ritual life, in legitimizing one’s presence at particular places through reference to the Dreaming, and in regulating marriage relationships between groups. [Source: Nancy E. Gratton, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

Pintupi society is strongly egalitarian and resists formal leadership structures. Authority rests with elders whose ritual knowledge and demonstrated ability to mediate and achieve consensus earn them respect. Because few decisions in traditional life required the involvement of large numbers, leaders primarily served as mediators in disputes rather than as figures of hierarchical authority. In mission-based settlements, elected councillors have taken on roles such as maintaining peace and distributing government resources, but hierarchical authority remains culturally unfamiliar and often uncomfortable for Pintupi.

Social control is usually maintained through the mediation of kin or friends. However, collective sanctions are applied in cases of serious transgressions, especially violations of sacred law, such as revealing ritual secrets.

Disputes can arise over many issues but are most frequent when large groups gather, often escalating into violent confrontations. Quarrels over women are especially common. In traditional practice, an aggrieved party might spear an opponent in the thigh and seek the backing of kin to avenge a wrong. Larger-scale hostilities are most likely to stem from acts of sacrilege. In sedentary settlements near mission stations, the frequency and severity of disputes have increased markedly, often aggravated by the introduction of alcohol.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Culture Shock! Australia, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated October 2025