Home | Category: Aboriginals

WIK MUNGKAN

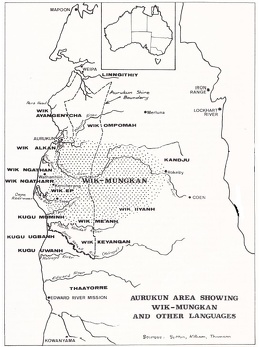

The are an Aboriginal Australian group of peoples who traditionally ranged over an extensive area of the western Cape York Peninsula in northern Queensland and speak the Wik Mungkan language. Also known as Munggan, Wik and Wikmunkan, they were the largest branch of the Wik people. In early ethnographic accounts of the region, the term "Wik Mungkan" was used to refer both to a specific language and to the "tribe" believed to speak it. Across the area, dialect names typically follow a common pattern: they are formed by adding a prefix meWik-Mungkan people aning "language" (i.e., "Wik-") to a distinctive word characteristic of that dialect. Accordingly, "Wik Mungkan" translates to "those who use mungkan to mean 'eating.'[Source: David F. Martin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

Traditionally, the various Wik-speaking peoples inhabited a broad region of western Cape York Peninsula in northern Queensland, spanning approximately between 13° and 14° south latitude. Their territory included the river systems of the area, the sclerophyll forests between them, and the coastal floodplains along the Gulf of Carpentaria to the west. The coastal zones, in particular, were characterized by significant ecological diversity and pronounced seasonal changes, with a short but intense monsoon season lasting two to three months, followed by a long dry season. |~|

A wide range of dialects were traditionally spoken by groups who identified their language as "Wik Mungkan." Due to the practice of dialect exogamy—marrying outside one's own clan or village—multilingualism was common, especially in the coastal regions. However, over time, and due to complex social and political changes, many of these original dialects are no longer spoken. In contemporary communities, Wik Mungkan and Aboriginal English have emerged as the primary lingua francas.

RELATED ARTICLES:

ABORIGINALS (FIRST NATION PEOPLE) OF AUSTRALIA: NAMES, DEMOGRAPHICS, LANGUAGES ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS IN QUEENSLAND: SOME GROUPS, CUSTOMS, LIFESTYLES ioa.factsanddetails.com

TORRES STRAIT ISLANDERS: HISTORY, TRADITIONAL LIFE, CULTURE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIANS IN NORTH NORTHERN TERRITORY: SOME GROUPS, CUSTOMS, LIFESTYLE ioa.factsanddetails.com

YOLNGU OF ARNHEM LAND: HISTORY, MUSIC, TRADITIONAL LIFE, CUSTOMS ioa.factsanddetails.com

TIWI PEOPLE OF NORTHERN AUSTRALIA: HISTORY, CUSTOMS, TRADITIONAL LIFE ioa.factsanddetails.com

EARLY MODERN HUMANS IN AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

LIFE OF EARLIEST HUMANS IN AUSTRALIA: TOOLS, WEAPONS, ART, SETTLEMENTS ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINALS AT THE TIME EUROPEAN COLONIZATION BEGAN ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIA ABORIGINALS FROM 1900 TO PRESENT: DISCRIMINATION, ASSIMILATION, SOME RESTITUTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIA’S STOLEN GENERATIONS: VICTIMS, LAWS, RATIONALE, OUTRAGE ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL RELIGION: TRADITIONAL BELIEFS, DEMOGRAPHY AND DEATH ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL CUSTOMS, SOCIETY AND RITUALS ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL LIFE: WHERE THEY LIVE, WORK, DIET, HEALTH, ALCOHOL ioa.factsanddetails.com

TRADITIONAL ABORIGINAL LIFE: FOOD, HOMES, HUNTING ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL MEN AND WOMEN: GENDER, MARRIAGE, SEX ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIAN SEX: PRACTICES, ATTITUDES, ADOLESCENCE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIAN ART ioa.factsanddetails.com

Wik Mungkan Population

The Wik-Mungkan language is spoken by an estimated 1,000 to 1,300 people, most of whom reside in the community of Aurukun in Queensland, Australia. According to the 2021 Australian Census, there were 947 recorded speakers of Wik-Mungkan—an increase of 115 percent compared to 2016. Smaller numbers of speakers are also found in communities such as Weipa, Edward River, Kowanyama, and Coen. [Source: Wikipedia |~|]

Based on the number of clans and their members, anthropologist Ursula McConnel inferred that the traditional Wik-Mungkan population likely numbered between 1,500 and 2,000 people. However, by 1930, McConnel estimated that only 50 to 100 remained around the Archer River and around 200 on the Kendall and Edward Rivers—a decline of approximately 60 to 75 percent. This significant demographic collapse was caused by a combination of factors, including coastal labor recruitment by traders, the spread of introduced diseases, displacement from traditional lands due to cattle grazing, and violent punitive expeditions aimed at destroying entire camps. In response to this upheaval, a coastal reserve was established for the Wik-Mungkan near the Gulf of Carpentaria around the turn of the 20th century.

Accurately estimating the pre-European population of the region is challenging. However, it is possible that around 2,000 Wik people lived in the less ecologically diverse inland sclerophyll forest areas, with at least as many residing in the more resource-rich coastal zones. Beginning in the late 19th century, the region experienced rapid depopulation due to a combination of factors, including outbreaks of measles and influenza, violent punitive raids by cattlemen, and the forced recruitment of men into labor on pearling and fishing vessels. In recent decades, however, the Wik population has seen growth again, supported by a high birth rate. |~|

Wik People History

Although the Cape York region may have once served as a significant migration route into the Australian continent, relatively little detailed archaeological or prehistoric research has been carried out in the areas traditionally inhabited by the Wik peoples. Linguistic and other forms of evidence indicate longstanding connections between various Wik groups and their coastal and inland neighbors. However, direct contact with Torres Strait Islanders or Makassan fishermen from Sulawesi in present-day Indonesia appears to have been limited along the west coast of Cape York.[Source: David F. Martin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

The first recorded European contact with the Wik people came from Dutch explorers in the early seventeenth century. However, significant external pressures began much later, particularly for inland Wik groups, with the arrival of cattlemen in the late nineteenth century. This period marked the beginning of widespread dispossession of traditional lands and a series of violent punitive expeditions—events that continued well into the twentieth century and remain within the living memory of some older Wik community members.

Along the coastal areas, the Wik people had sporadic contact with itinerant timber cutters over many years. However, the most severe disruptions came from bêche-de-mer fishermen operating in the Torres Strait, who actively sought Indigenous labor, often with exploitative consequences. In part due to growing public concern over these conditions, Christian missions were established in the remote regions of Cape York from the early 1900s. These missions operated within the Queensland government’s assimilationist policies and legal framework, promoting the gradual sedentarization of the Wik. Through systematic efforts, they aimed to replace traditional semi-nomadic lifeways with a settled village-based social, political, and economic structure.

A major turning point came in 1978 with the introduction of secular local governance under the state’s local government model. This shift was accompanied by a dramatic increase in funding, infrastructure development, and bureaucratic oversight. While these changes brought new resources, they also placed considerable strain on traditional Wik social systems and internal governance.

In response to a claim brought by Wik and Thayoree Aboriginals, an Australian High Court ruled 4 to 3 in 1996 that Aboriginals who prove a traditional connection to their land could claim property rights and coexist on land leased by sheep and cattle ranchers (known as pastorialists in Australia) and mining companies. The ruling is known as the Wik Decision. The Wik claim pitted 188 traditional Aboriginal claimants against 19 defendants in battle over 10,000 square miles in the Cape York Peninsula, which includes one of the world's richest bauxite deposits.

Pastoral leases account for 40 percent of Australia's total land area and gold and base metal mining companies also use pastoral claims to obtain land. The intent of the Wik ruling, the court said, was to allow Aboriginals to hunt and conduct religious ceremonies on pastoral leased land but miners and ranchers worried the decision made pastoral lease vulnerable to Aboriginal claims for compensation on development. They lobbied the government to pass legislation limiting Aboriginal rights. Many of the rancher defendants in the Wik claim had nothing against the Aboriginals who brought the claim but did resent the lawyers and anthropologists who earned large sums of money off of it. The ranchers wanted an agreement that gave them title to the land in exchange for giving the Aboriginals access to it.

Wik Mungkan Religion

According to Wik belief, culture in its broadest sense—including land and its sacred sites, languages, totems, rituals, body-paint designs, technologies, and the foundations of social relations—is not seen as the product of human creativity. Rather, it is understood to have been "left behind" by ancestral culture heroes. [Source: David F. Martin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

In the coastal regions, these heroes are typically represented by two brothers whose mythic journeys form the basis of ritual cults. These cults transcend individual clan totemism and serve to unite clans through broader regional affiliations. Among inland Wik groups, the founding ancestral figures of clans are usually identified with their major totemic species. This "Creation Time"—a period of heroic activity and transformation—is considered just beyond the living memory of the oldest community members. However, its spiritual power is continually renewed and made present through ritual performance.

The Wik cosmology is also inhabited by a range of spiritual beings, including the spirits of the dead and various nonhuman entities—some of which are malevolent. Like humans, these beings are considered to have language and territorial associations. While many Wik today are nominally Christian, traditional beliefs remain deeply influential, and religious practices often reflect a syncretic blend of Christian and ancestral elements.

By the 1990s, there were still ritual specialists among the Wik, although their numbers were limited and knowledge of many ceremonial and initiatory traditions had become fragmented. Importantly, ritual authority does not necessarily translate into secular leadership, especially within contemporary settlement life.

Death and Afterlife: Among coastal Wik communities, it is believed that a person possesses at least two spiritual elements. Upon death, what may be thought of as the "life essence" departs westward over the sea. Meanwhile, the "earthly shadow" lingers, inhabiting the places and objects the person used in life. Over time, purification rites are performed to resocialize these belongings and spaces. Additionally, the individual's totemic spirit is ritually sent to the clan's spirit-sending center a few days after death—though this specific rite is not observed among inland Wik groups. Since the introduction of mission influence, cremation has largely been replaced by burial, and Christian services are now typically incorporated into mortuary ceremonies.

Wik Mungkan Marriage and Family

Among the Wik Mungkan, the preferred form of marriage traditionally involved classificatory cross-cousins—that is, cousins who are the children of a brother and sister. However, at least one group of Wik Mungkan speakers exhibited a marked preference for actual (biological) cross-cousin marriages and relationships. There were also numerous marriages that occurred before significant European influence which did not follow either pattern; these were referred to as "wrong-head" marriages. In the coastal areas, dialect exogamy—marrying outside one’s own clan or village—was common. At the same time, marriages tended to cluster within relatively endogamous regional groupings, often shaped by the ecological divide between coastal and sclerophyll forest zones, as well as by shared affiliation with specific totemic ritual cults.[Source: David F. Martin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

Traditionally, local groups typically consisted of several "households," usually centered around a senior male, his wife or wives, their children, and sometimes in-laws or elderly parents. These residential groups often also included a separate camp for unmarried men. In contemporary settlements, household composition is even more fluid, with frequent changes in who lives where and with whom. The household remains a fundamental unit for activities such as resource use, food distribution, caregiving, and child-rearing—but it is not necessarily tied to a single dwelling or fixed physical space. |~|

In Wik society, while the day-to-day responsibilities of child-rearing typically fall to women, men—including fathers, uncles, and older siblings—also actively engage in caring for and playing with young children. Children are generally indulged, and after weaning, they spend much of their time playing with siblings and peers from related kin groups. Learning traditionally occurred through observation and participation rather than in formal settings, with the notable exception of male initiation ceremonies. This pattern of socialization was significantly disrupted by the missions, which placed children in dormitories, separating them from their families until the dormitory system was abolished in 1966. Today, many older Wik express deep concern over what they see as a breakdown in social control over children and youth—an issue that leaves them feeling powerless and disconnected from their traditional roles in guiding the next generation.

With respect to inheritance, land, its sites, their associated rituals and mythologies, the totems, the rights to the pool of clan names (which serve as indirect references to the totems), and membership in totemic ritual cults are all passed down patrilineally (through the male line). However, certain rights of access to land and specific sites may also be obtained through factors such as marriage or residence within the landowning group.|~|

Wik Mungkan Kin Groups and Land Tenure

Among the Wik Mungkan, it is important to distinguish between actual social groups formed for specific purposes—such as residence or warfare—and clan membership. While clan affiliation provides the framework against which such groups are understood, residential groups in the bush may include members of several clans. These groups can comprise not only the core clan but also spouses, visitors from neighboring estates, and individuals whose kinship ties grant them legitimate rights of residence. Kinship Terminology is essentially of the simple Dravidian type, in which grandparents are classified into parallel and cross categories.[Source: David F. Martin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

Clans are patrilineal (traced through the male line), exogamous, and landholding units, though genealogical depth is shallow and seldom extends beyond two or three generations. Membership is not static: schisms are common, often arising from conflict and, in the past, possibly environmental or demographic pressures. In daily life, however, bilateral kinship ties carry greater significance than clan solidarity, which tends to be expressed primarily in major conflicts and mortuary rituals.

Early ethnographers presented the Wik as organized into patrilineal, landholding clans that aggregated into dialectal tribes, each clan estate containing sites associated with its distinctive totems. Along the Archer River and in the sclerophyll-forest region, there is evidence of a close correspondence between clan estates and their totemic sites, as well as relatively low linguistic diversity compared with the coast. In coastal and inland areas alike, the ideological model emphasizes patrilineal totemic clans with bounded estates—best understood as custodianship rather than outright ownership.

In practice, the situation is far more complex. Land tenure, totemic affiliations, ritual cults, and linguistic ties often crosscut one another. This complexity is compounded by the extinction of certain landholding groups, leaving estates vacant. Claims to land and sacred sites may also be made through the maternal line, extending as far as the grandparental generation. Moreover, it is essential to distinguish between rights of tenure (the formal custodianship of land) and rights of access (the ability to use or occupy land under particular circumstances).

Traditional Wik Mungkan Life and Economic Activity

Traditionally, the Wik Mungkan had a more limited range of movement during the wet season, when communities were largely confined to camps located on higher ground, usually centered around a senior male within his clan estate. In the dry season, groups dispersed more widely, establishing base camps near lagoons and lakes. Travel during this period was motivated not only by subsistence but also by the need to gather for ritual activities and to enjoy broader social interaction after the relative isolation of the wet-season camps. Today, most Wik people reside in small townships and settlements situated on the fringes of their ancestral lands. [Source: David F. Martin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

The Wik were hunters and gatherers, their activities shaped by the flat terrain and seasonal variation in resources. The wet season brought scarcity, coinciding with restricted movement. In the dry season, lagoons and lakes provided abundant resources such as fish, swamp tortoises, birds, and water-lily roots. Yams were gathered in large quantities from sand-ridge country, while estuarine waters supplied fish and crustaceans. The subsistence base has been radically transformed in contemporary settlements, particularly since the large-scale introduction of a cash economy in the late 1960s. While some Wik continue to spend time on or near their traditional estates, supplementing incomes with hunting and fishing, the main source of livelihood today is government transfer payments. Most efforts to establish viable industries—such as cattle raising—have not succeeded.

Wik material culture was comparatively complex within Aboriginal Australia. Distinctive items included spears and spear-throwers, woven bags, and fishing nets—many of which now support a small handicraft trade catering primarily to urban markets. Archaeological and ethnographic evidence indicates long-distance trade: pearl shells from the Torres Strait were likely introduced by northern and eastern neighbors, while stone axes and stingray barbs were traded out. Regional exchange also included spear handles, ochres, and resins. Importantly, such trade was rarely purely economic, serving instead broader social, political, and ritual purposes—a pattern that continues in modified form today.

Although the general pattern positioned men as hunters and women and children as gatherers, the division of labor was more nuanced. Tasks varied with the life stage of individuals and the composition of foraging groups. Both men and women fished, though women seldom used spears, and they never hunted game with rifles or spears. Items associated with each gender’s activities were usually made by members of that sex, though exceptions existed—some women made spears, for instance. Food was typically prepared by the person who obtained it: men cooked game, while women prepared vegetable foods. Today, however, men are also commonly seen baking bread in ashes. Contemporary divisions of labor have been strongly influenced by cattle stations, missionaries, and European settlement staff. Only men work in cattle mustering, mechanics, or heavy equipment operation, while roles such as nurses’ aides and health workers are occupied exclusively by women. More recently, some men have begun working as teachers’ aides and clerical staff.

Wik Mungkan Rituals, Medicine and Art

Minor Wik ceremonies included those held at totemic increase sites, while the major rituals surrounded birth, male initiation, and the elaborate cycle of mortuary practices. Totemic ritual cults featured prominently in both initiation and mortuary rites. Land, its sacred sites, and the relationships of individuals and groups to these places lay at the heart of ceremonial and social life. [Source: David F. Martin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

Many rituals were, and in some cases remain, relatively public, involving men and women in defined roles. Others were once restricted but are now rarely so. Women conducted particular rites within mortuary cycles and at some increase ceremonies at clan totemic sites, but they did not possess a fully autonomous ritual sphere, aside from ceremonies connected with childbirth. Today, mortuary rituals—though transformed from their precontact forms—continue to be central to settlement life, whereas initiation and birth ceremonies are no longer practiced.

Illness and misfortune were traditionally attributed either to sorcery (always performed by men) or to ritual transgressions, such as entering a dangerous sacred site without proper rights. Healers, known today as “murri doctors,” counteracted sorcery through their own ritual practices. Alongside this, practical remedies such as bark poultices and herbal infusions were employed for ailments like wounds or diarrhea, though their use was not limited to healers and often varied idiosyncratically.

Since the 1950s, the Wik have produced carved and painted ceremonial objects representing totemic figures of major ritual cults for use in public and semi-public ceremonies. Earlier, such objects were simpler, more abstract, and reserved for secret rituals. Distinctive clan-owned body-paint designs, once more widely used, now appear only in mortuary rites. In recent years, small-scale art workshops have emerged, producing items such as screen-printed cards and clothing, extending ceremonial aesthetics into new cultural and economic contexts.

Wik Mungkan Social and Political Organization

For the Wik Mungkan, kinship provided the central framework through which social relations and organization were interpreted. Alongside kinship, other forms of association included the inland/coastal division, regional marriage clusters, loose geographic groupings, short-term collectivities for seasonal economic activities or initiation ceremonies, and the overarching regional totemic ritual cults. [Source: David F. Martin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

Although clan and family structures in the settlements have undergone major changes—and many precontact regional and ritual associations have weakened or disappeared—kinship remains the primary idiom of everyday life. At the same time, new forms of association have emerged, organized around wage labor, alcohol consumption, and the administrative and governing bodies established in the settlements.

A distinctive feature of coastal Wik society, though less pronounced inland, is the concept of “bosses.” These were men recognized for their deep knowledge of country and ritual, political skill, fighting ability, oratory, and capacity to mobilize kin. Women, particularly in older age, could also assume leadership roles, though their influence was generally more circumscribed. Typically, each clan had a senior man or woman acknowledged as a “boss,” and regional leaders emerged from this pool of clan spokespersons.

Despite their authority in matters such as ceremonies, alliances, and camp locations, bosses operated within a cultural context that resisted hierarchical authority and strongly valued personal autonomy in daily life. Contemporary political organization in the settlements is dominated by elected councils modeled on European local-government systems. While framed as instruments of self-determination, they function largely according to European agendas. Almost all service and administrative positions are filled by White Australians or other non-Wik, leaving the ultimate control of Wik affairs in the hands of the state.

Conflict has long been a pervasive element of Wik society. Traditionally, one key mechanism for managing it was “resolution by fission,” in which individuals or groups could physically separate themselves from disputes. This strategy has been largely undermined in the settlements, which were designed as compact townships for administrative convenience, restricting people’s capacity to disperse.

Today, many conflicts stem from unsanctioned sexual relations, as parental and grandparental generations no longer exert control over young people’s sexuality. The absence of male initiation rituals—discontinued for over twenty years—has further weakened traditional avenues of social regulation. Widespread alcohol consumption has compounded these problems, contributing to high levels of interpersonal violence. Such circumstances increasingly draw bureaucratic intervention, further entrenching state control over Wik social life.

See Important Mabo and Wik Aboriginal Land Rights Decisions Under AUSTRALIA ABORIGINALS FROM 1900 TO PRESENT: DISCRIMINATION, ASSIMILATION, SOME RESTITUTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Culture Shock! Australia, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated September 2025