Home | Category: Aboriginals

WESTERN AUSTRALIA

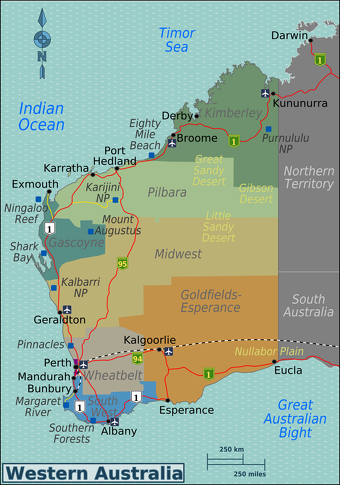

Western Australia is the largest state in Australia. It is about as large as the entire western United States west of the Rockies. Most of it lies on a harsh, barren, broad plateau. The northern and western coasts border the Indian Ocean. The southern coast borders the Southern Ocean. West Australians are so isolated from other Australians they are referred to as sandgropers — a grasshopper-like insect that swims through the sand — by people in the rest of the country.

The northwestern part of Western Australia, a chunk of land in larger than Alaska, is home to only 100,000 or so people, many of them Aboriginals or miners who commute hundred of miles very month to see their families in Perth. In much the northern part of Western Australia, the Outback runs right to the sea. Large chunks of land here are owned by Aboriginals. The most interesting areas here are the Kimberly in the extreme north, a region with a rugged coastline and deep gorges, and the Pilbara region, further south, in the in the central Western Australia Outback, with magnificent rock scenery, vast mineral wealth (mostly natural gas and iron) and blistering hot temperatures. Pilbara ironically means "fish" in the local Aboriginal language. Most of the towns in the regions are connected somehow to the mining industry. If you drive here, be prepared with lots of water and fuel.

Some of the world's oldest known paintings were found in Western Australia. The Yirra site in the eastern Pilbara region is one of the oldest known archaeological sites in Australia, with evidence of human presence dating back over 50,000 years — a date determined by analysis of stone tools, charcoal, and bone at the sacred Yinhawangka site. Because Western Australia is closest part of Australia to Europe it was the first part of the continent first reached by Europeans. The Dutch were the first to arrive, followed by the British and the French. It was first settled in the 1820s, mainly to keep out of the hands of the French.

Today, about 85 percent of Western Australia's population live in and around Perth in the southwestern corner of Western Australia. This part of the state has a Mediterranean climate with dry, warm summers and rainy winters, forests and major agricultural areas with wheat, cattle and sheep, and even a wine growing region. A range of small mountains separates this livable region from the inhospitable outback and the Nullubar Plain. Kriol, major Aboriginal contact language, is spoken in regions like Katherine and across the Kimberley. It is considered a new Indigenous language that emerged after European settlement.

RELATED ARTICLES:

ABORIGINALS (FIRST NATION PEOPLE) OF AUSTRALIA: NAMES, DEMOGRAPHICS, LANGUAGES ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS OF CENTRAL AUSTRALIA: SOME GROUPS, CUSTOMS, ART, LIFESTYLE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIANS IN NORTH NORTHERN TERRITORY: SOME GROUPS, CUSTOMS, LIFESTYLE ioa.factsanddetails.com

EARLY MODERN HUMANS IN AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

LIFE OF EARLIEST HUMANS IN AUSTRALIA: TOOLS, WEAPONS, ART, SETTLEMENTS ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINALS AT THE TIME EUROPEAN COLONIZATION BEGAN ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIA ABORIGINALS FROM 1900 TO PRESENT: DISCRIMINATION, ASSIMILATION, SOME RESTITUTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIA’S STOLEN GENERATIONS: VICTIMS, LAWS, RATIONALE, OUTRAGE ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL RELIGION: TRADITIONAL BELIEFS, DEMOGRAPHY AND DEATH ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL CUSTOMS, SOCIETY AND RITUALS ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL LIFE: WHERE THEY LIVE, WORK, DIET, HEALTH, ALCOHOL ioa.factsanddetails.com

TRADITIONAL ABORIGINAL LIFE: FOOD, HOMES, HUNTING ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL MEN AND WOMEN: GENDER, MARRIAGE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIAN SEX: PRACTICES, ATTITUDES, ADOLESCENCE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIAN ART ioa.factsanddetails.com

Aboriginals and Aboriginal Groups in Western Australia

In 2021, 88,693 people in Western Australia identified themselves as Aboriginal, making them 3.3 percent of the state's total population. This population grew by 17 percent between the 2016 and 2021 censuses. The Aboriginal population in Western Australia is younger than the non-Indigenous population, with fewer people in older age groups. In 1981 the Aboriginal population of Western Australia was estimated at 31,351. [Source: Google AI]

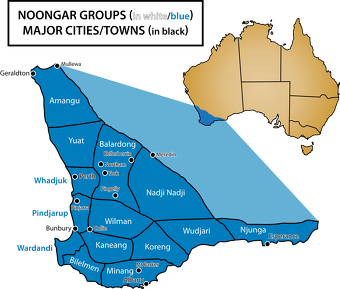

Major Western Australian Aboriginal cultural groups include the Noongar in the southwest, the Yamatji in the Mid-West and Gascoyne-Murchison, the Western Desert cultural bloc (including groups like the Martu and and the Wongi people of the Goldfields), and the Kimberley peoples. These groups are diverse, with the Noongar consisting of 14 language groups.

The Yamatji includes localized language groups such as Amangu, Naaguja, Wadjarri, Nanda, and Badimia people. The name given to a number of closely related and affiliated Aboriginal groups who lived in the deserts of western Australia. Known groups included the Koreng, Minang, Pibelman, Pindjarup, Wardardi, and Wheelman. All of the Yungar groups are either totally or nearly extinct.

The Karajarri (also spelled Garadjara, Karadjeri, Garadjui, Guaradjara, Karadjari) are an Aboriginal Australian people of Western Australia. They live south-west of the Kimberleys in the northern Pilbara region, predominantly between the coastal area and the Great Sandy Desert. They now mostly reside at Bidyadanga, south of Broome. To their north live the Yawuru people, to the east the Mangala, to the northeast the Nyigina, and to their south the Nyangumarta. Further down the coast are the Kariera. In the 1990s they were located in the area of Roebuck Bay and inland to Broome. In 1984 there were only 35 individuals. Karadjeri is classified in the Pama-Nyungan Family of Australian languages. The Karadjeri were hunters and gatherers with their subsistence territory defined with reference to various religious and sacred sites. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

The Kukatja people live in the Tanami and Great Sandy Deserts of Western Australia, with communities around Balgo and Lake Gregory. Kukatja also refers their language, an endangered indigenous language that belongs to the Pama-Nyungan language family and is a dialect of the Western Desert language. It is known for its free word order and continuous phrase structure. The Kukatja language also includes a complex system of hand talk, which allows for non-verbal communication over long distances and expresses nuance. The Kukatja language was spoken by about 580 people in the 1996 census. According to “Growing Up Sexually: Father Peile did some observations on the Kukatja who allegedly “did not frown upon occasional sexual liaisons between a father and his adolescent daughter, a practice they regarded as contributing to her physical development"; here the term "taltja" is in place. When somebody once commented to a mother about her daughter's behaviour, the lady replied, "She got to get big". [Source: “Growing Up Sexually, Volume” I by D. F. Janssen, World Reference Atlas, 2004]

Kimberley Region and Aboriginal Groups There

The Kimberley Region is vast, remote 106,700-square- kilometers (410,00-square) mile region in northwest Western Australia with less than 50,000 people, 15 percent of whom are Aboriginals. Bounded by the Timor Sea and Indian Ocean to the north and the Great Sandy Desert to the south and the Northern Territory border to the east, it boasts some of the wildest desert scenery in the world, including beehive-shaped rock domes with thin red, orange and black stripes, boab trees, rough sandstone cliffs and deep gorges.

The 19th explorer Sir George Grey wrote, "The country in which I had landed was of a more rocky and precipitous nature than any I had ever before seen. Indeed, I could not more accurately describe the hills by saying that they appeared to be a ruins of hills, comprised as they were of huge blocks of red sandstone, confusedly piled together in loose disorder."

Indigenous communities in Western Australia based on Australian Bureau of Statistics data from 2006l 1) Large red dot: 500 people or more; 2) Medium red dot: 200 to 499; 3) Small red dot: 50 to 199; 4) Small back dot: less than 50 people

In the Kimberley Region there are a number of Aboriginal tours, many of them sponsored by local Aboriginals. The Kimberley region has a Wet and Dry climate like the Northern Territory. The wet season last a few months and falls sometime between November to March, when torrential rain storms can transform plains into lakes, cliffs into water falls and deserts into fields with cane grass that grow ten feet in less than a month.

The Kimberley region is home to many diverse Aboriginal groups, including the Bunuba, Gooniyandi, Kija, Mangala, Marra Worra Worra, Miriwoong, Nyikina, Walmajarri, Wangkajungka, and Worrorra people, among others. These groups have unique languages and cultural practices, with some having established organizations like the Marra Worra Worra Aboriginal Corporation and the Wilinggin Aboriginal Corporation to support their communities and manage land rights. Fitzroy Valley Groups include peoples like the Bunuba, Gooniyandi, Nyikina, and Walmajarri peoples. Among the West Kimberley Groups are the Warrwa, Bardi, and Worrorra. The Shire of Wyndham East Kimberley recognizes groups such as the Doolboong, Kija, and Miriwoong people.

History of Western Australian Aboriginals

The oldest archeological sites in Western Australia include sites on Barrow Island and in the Western Desert, with evidence of human occupation dating back at least 50,000 years. Boodie Cave on Barrow Island shows use between 50,000 and 30,000 years ago. Karnatukul (Serpent's Glen) — located in the Carnarvon Ranges of the Western Desert — is also around 50,000 years old. it is the oldest known site in the Western Desert and provides insights into how the first people in Australia used wattle for food, medicine, firewood, and tools. Archaeological evidence from around 10,000 years shows local people in southwest Australia were using quartz for spear and knife edges after rising sea levels submerged earlier chert sources.

Most of the first Europeans to explorers Australia were Dutch and the first places they reached were in western Australia. Dirk Hartog was blown into the west coast of Australia and scoped it out a bit. Frederick de Houtman did the same in 1619.The first real contact between Western Australian Australia with Europeans was when the first settlers began arriving in the 1820s. Many Aboriginal peoples saw the arrival of Europeans as the return of deceased relatives and imagined them as such. As the newcomers approached from the west, they were called djaanga (or djanak), which means "white spirits." However, it wasn't long before relations deteriorated. See History of the Noongar Below. [Source: Wikipedia]

Bryte and acclaimed Indigenous actor/director Curtis Taylor at the Noongar Pop Culture launch at Leedaville HQ, Perth, 2014

In June 1832, the Whadjuk Noongar leader Yagan — once respected by settler authorities for his bearing and stature — was declared an outlaw along with his father Midgegooroo and brother Monday, following food raids and a retaliatory killing. Captured and imprisoned, Yagan escaped, and for a time was left unmolested, his reputation elevated into a kind of Aboriginal William Wallace figure. His father, however, was executed without trial by a firing squad. Soon after, Yagan was ambushed and killed by an 18-year-old settler youth while asking settlers for flour. His head was severed and sent to England for public display. Today, Yagan is remembered by all Aboriginals as a hero and is widely regarded as one of the first Aboriginal resistance leaders.

Beginning in 1838, Aboriginal prisoners began to be sent to Rottnest Island near Perth. Initially shared with settlers, the island was formally designated an Aboriginal prison in 1841. For more than six decades, until 1903, Rottnest functioned as a penal site to forcibly remove Aboriginal men and boys from their homelands. Prisoners were often rounded up and chained for acts such as spearing livestock, setting fire to bushland, or digging up native foods on lands they had always inhabited. Conditions were harsh, and Rottnest became known as a place of torment, deprivation, and death. It is estimated that as many as 369 Aboriginal prisoners lie buried on the island, including five men who were hanged. In total, around 3,700 Aboriginal men and boys from across Western Australia were imprisoned there, making Rottnest one of the most significant sites of colonial injustice in Aboriginal history.

Aboriginal Art from Western Australia

Aboriginal art from Western Australia is very diverse, ranging from ancient rock engravings in the Pilbara region to modern ochre-based artworks and acrylic paintings from the Kimberley and desert areas. Key artistic traditions include cave and rock paintings with hand stencils and depictions of ancestral beings, as well as ochre art from the Kimberley, which uses thick, natural pigments to create a distinct texture.

Kimberley is known for its unique Ochre Art, where artworks are created using natural ochre pigments from the land, resulting in a thick, crusty, and rough finish. Key sites include rock art near Kununurra and the petroglyphs of the Murujuga (Burrup Peninsula). The Golden Outback: is to ancient rock art sites like Walga Rock and Mulka's Cave, featuring ancient hand stencils, depictions of ships, and illustrations of Dreamtime stories and ancestral spirits.

Central and Western Desert: Features vibrant acrylic paintings, often incorporating the well-known "dot painting" style. Many feature: 1) Dreamtime Stories about the creation of natural wonders, and the spiritual connection to the land; 2) Wandjina Ancestral Beings, with their large, haloed heads, represent ancestral spirits and rain-makers; 3) Native Fauna and Flora, some now extinct, and significant plants; and 4) Hand Stencils, a common technique where a hand is pressed to a rock and pigment is blown over it, creating a negative impression.

Aboriginal art from the Kimberley region of western Australia is known best for its images of Wandjina, ancestral beings who came from the sky and usually depicted with a hallo. large eyes and nose but no mouth. The beings were often found in rock paintings in the area and are believed to have created many of the Dream Place natural features.

See Separate Articles:

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL ART FROM DIFFERENT REGIONS ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

VERY, VERY OLD AUSTRALIAN AND ABORIGINAL ROCK ART ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

RITUAL LIFE AND MYTHS OF ANCIENT AUSTRALIANS ioa.factsanddetails.com

LIFE OF EARLIEST HUMANS IN AUSTRALIA: TOOLS, WEAPONS, ART, SETTLEMENTS ioa.factsanddetails.com

PEOPLE WHO LIVED AUSTRALIA 20,000 TO 10,000 YEARS AGO ioa.factsanddetails.com

Sexual Practices in Western Australia Children in the Old Days

Cawte (1964) wrote on a Northwestern tribe: “The children, accustomed to their parents’ sexual intercourse, play sexual games at the age of four with the realism that would horrify a Western mother. The schoolteacher tries to teach them alternatives such as hide-and-seek but “they never get it off their minds”. [Source: “Growing Up Sexually, Volume” I by D. F. Janssen, World Reference Atlas, 2004]

Abbie (1969) wrote: “The children, like children everywhere, play “grown-ups” and “mothers and fathers”, and being better informed than most white children they carry the game further and attempt to bring it to its logical conclusion. No doubt the more physically precocious succeed...Aboriginal parents tend to view it with amused indulgence provided the proper kinship relations are observed- in the north at least”.

Róheim (1962) on Central Australian Aboriginals wrote: “We may confidently affirm that there is no latency period in the life of these people, no period in which they do not make more or less successful attempts at coitus”. Róheim relates that “their only, and certainly their supreme, game was coitus”. Róheim(1974) made an extensive study of children’s play sessions both in camp and in the bush using animal puppets. The play reveals much “orificial” material, and a large amount of coital enactments. Native dolls may also provide outlets of sexual material; in at least some tribes, the genital organs are said to be the “most prominent part” of the dolls (Hernández, 1941).

Noongar

The Noongar are an Aboriginal Australian people that live in the south-west corner of Western Australia from Geraldton on the west coast to Esperance on the south coast, with a large concentration in the Perth metropolitan area. Also known and spelled as Noongah, Nyungar, Nyoongar, Nyoongah, Nyungah, Nyugah, and Yunga, the Noongar cultural bloc comprise 14 different groups; Amangu, Ballardong, Yued, Kaneang, Koreng, Mineng, Njakinjaki, Njunga, Pibelmen, Pindjarup, Wadandi, Whadjuk, Wiilman and Wudjari. The Noongar people refer to their land as Noongar boodja. The word Noongar comes from a word originally meaning "man" or "person". [Source: Wikipedia]

Members of the Noongar cultural group are descended from people who spoke several languages and dialects that were often mutually intelligible. What is now classified as the Noongar language belongs to the large Pama–Nyungan language family. At the time of European settlement, the peoples of what became the Noongar community are believed to have spoken thirteen dialects, five of which still have speakers with some knowledge of their respective languages. Most contemporary Noongar trace their ancestry to one or more of these groups. No speakers use the languages in all everyday situations, and only a few individuals have access to all the languages' resources. Contemporary Noongar speakers use Australian Aboriginal English, a dialect of English, laced with Noongar words and occasionally inflected by Noongar grammar.

The estimated Noongar population is around 30,000 to 40,000 people with Noongar ancestry, representing a significant portion of the Aboriginal population in Western Australia. The 2021 Census showed 89,000 people identified as Aboriginal in Western Australia, with the Noongar people making up a large part of this group. Noongar numbers were historically impacted by the arrival of British colonists, but they have since recovered to levels near or possibly exceeding pre-colonial numbers. The 2011 Census recorded 10,549 Noongar people, with this number increasing to 14,355 by 2021, indicating significant growth in self-identified Noongar population. The South West Native Title Settlement, the largest native title settlement in Australian history, encompasses a vast area and affects many Noongar people.

History of the Noongar

Before European arrival, the Noongar population has been variously estimated at between 6,000 and several tens of thousands. British colonisation brought both violence and epidemic disease, causing a devastating decline. [Source: Wikipedia]

Early relations were often cordial. When Matthew Flinders visited for three weeks in 1801, he credited the success of his stay to Noongar diplomacy, and local rituals incorporated the newcomers in ceremonial form. But as permanent settlement expanded, tensions grew. Noongar systems of reciprocity clashed with settler notions of private property, particularly as the fertile Upper Swan lands were occupied. Fire-stick farming — the practice of setting controlled burns in summer — was misinterpreted as arson, while the Noongar, in turn, saw settlers’ livestock as legitimate prey, replacing native animals that had been hunted out or shot by colonists. Such misunderstandings escalated into violent confrontations (see Yagan above).

From 1890 to 1958, Noongar lives were heavily regulated under the Native Welfare Act. By 1915, around 15 percent of Perth’s Noongar population had been forced north and confined at the Moore River Native Settlement. Carrolup (later Marribank) also became home to as much as one-third of the Noongar community. During this period, between 10 and 25 percent of Noongar children were forcibly removed from their families and placed in missions, foster homes, or institutions. This policy formed part of what is now remembered as the Stolen Generations, leaving profound and lasting scars on Noongar society.

Noongar Life and Culture

The Noongar recognise six distinct seasons, each defined by observable changes in the natural world, with the dry period ranging from as few as three months to as many as eleven. The six seasons are: 1) Birak (December/January, the Dry and hot when Noongar burned sections of scrubland to force animals into the open for easier hunting; 2) Bunuru (February/March), the hottest part of the year with sparse rainfall; 3) Djeran (April/May), when cooler weather begins, fishing is good and bulbs and seeds are collected for food; 4) Makuru (June/July), cold fronts move further north, bringing rain and making this the wettest time of the year; 5) Djilba (August/September), often the coldest time of the year with clear, cold nights and days or warmer, rainy, and windy periods; and 6) Kambarang (October/November), when a warming trend is accompanied by longer dry and fewer cold fronts crossing the coast. It is when many wildflowers bloom. [Source: Wikipedia]

Noongar territory spans three broad geological systems — the coastal plains, the plateau, and the plateau margins — all generally characterised by infertile soils. Vegetation varies: casuarina, acacia, and melaleuca thickets dominate the north, while the south supports mulga scrublands and dense forests. Rivers, lakes, and wetlands provided vital food resources and shaped the Noongar way of life.

From Wunambal Gaambera

Traditionally, Noongar subsistence combined hunting, fishing, and plant gathering. Kangaroos, wallabies, and possums were hunted inland, while those near rivers or the coast relied on spear-fishing or trapping. Plant foods were extensive, from yams and wattle seeds to the toxic nuts of the zamia palm, which required elaborate processing during the Djeran season (April–May) to make them safe to eat. While some have speculated that zamia nuts were used as a contraceptive, there is no direct evidence for this.

Today, Noongar people are concentrated in Perth and other major towns across the southwest — including Mandurah, Bunbury, Albany, Geraldton, and Esperance — as well as in smaller country towns. Many families maintain long-standing relationships with local farmers and continue to hunt kangaroos, gather bush foods, and pass on stories of the land to younger generations. Local bush tucker includes kangaroo, emu, quandong jam, bush tomatoes, witchetty grub pâté, and bush honey.

The buka, a traditional kangaroo-skin cloak, remains an emblematic garment of the Noongar people. The kodj (or kodja, meaning “to be hit on the head”) is a distinctive hafted axe, once widely used across Noongar country. The town of Kojonup and its cultural centre, The Kodja Place, commemorate this important tool.

Wunambal

The Wunambal (also known as Unambal, Wunambal Gaambera, Uunguu and other names) are an Aboriginal Australian people of the northern Kimberley region of Western Australia. They were according to Norman Tindale, "perhaps among the most venturesome of Australian Aboriginals". They made rafts that could withstand the rip currents and high that varied as much as 12 meters (39 feet) in the seas where they lived. They learned by make the sailing crafts from from Makassan visitors from present-day Sulawesi in Indonesia and used these crafts to make sailing forays out to reefs (warar) and islets in the Cassini and Montalivet archipelagoes, and as far as the northerly Long Reef. The Wunambal bands who excelled in this were the Laiau and the Wardana.

The Wunambal, Worrorra, and Ngarinyin peoples form a cultural bloc known as Wanjina Wunggurr. The shared culture is based on the dreamtime mythology and law whose creators are the Wanjina and Wunggurr spirits, ancestors of these peoples. The Wunambal Gaambera Aboriginal Corporation represents the Wunambal Gaambera people; Uunguu refers to their "home", or country.

The Wunambal were organised into the following groups: 1) Laiau, 2) Wardana (now extinct), 3) Winjai (eastern), Kanaria (northeastern group near Port Warrender) and Peremanggurei The traditional lands of the Wunambal are around York Sound. Norman Tindale estimated their tribal domains encompass roughly 9,800 square kilometers (3,800 square miles), running north from Brunswick Bay, as far as the Admiralty Gulf and the Osborne Islands. Their inland extension reached about 40 kilometers (25 miles) inland.

As part of the same native title claim lodged in 1998 by Wanjina Wunggurr the Wunambal people were given the claim to over 25,909 square kilometers (10,004 square miles), most of which was determined as exclusive possession. The claim includes the waters of Admiralty Gulf and York Sound, down to Coronation Island and parts of the Mitchell River National Park and the Prince Regent National Park. In 2012, they were given native title rights to part of 44,768 square kilometers (17,285 squar miles) area in the Shire of Wyndham-East Kimberley.

On the sexual practices of the Wunambal in the 1940s, Lommel (1949) described “a rather clumsily executed defloration to make a girl “ready” for intercourse. After that, so it is said, a girl lived for some time until her marriage in promiscuity with all those men to whom she was according to her relationship an eligible wife. This custom still prevails, so I was told, in missions where it is officially prohibited and therefore practiced secretly at night only...The crude defloration is performed by an elder man of the same marriage-group as the girl. He, so I was told, wraps round his finger some thread spun from kangaroo-hair, and executes the defloration with it. After that the men of her intermarrying group who happen to be present have intercourse with her” [Source: “Growing Up Sexually, Volume” I by D. F. Janssen, World Reference Atlas, 2004]

Kariera

The Karieri people were an Aboriginal Australian people of the Pilbara, who once lived around the coastal and inland area around and east of Port Hedland. The term Kariera refers both to a specific Aboriginal people of Western Australia, with their own language and identity, and to a broader form of social organization and kinship reckoning shared by several neighboring groups, including the Nglera, Ngaluma, Indjibandi, Pandjima, Bailgu, and Nyamal. The Kariera system is associated with the drainage of the De Grey River and parts of the Fortescue River region. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

Like other Western Australian peoples, the Kariera were traditionally hunters and gatherers, organized into small local bands centered on nuclear families. Each band exploited a portion of the wider Kariera territory. The Kariera employ a classic “four-section” system of descent. Two patrilineal, exogamous moieties are crosscut by two matrilineal moieties, creating a system of reciprocal wife-giving and wife-taking. In this arrangement, a man is expected to marry his mother’s brother’s daughter or his father’s sister’s daughter, thus marrying a classificatory cross cousin. Because the system is reciprocal, it also implies sister exchange, at least in classificatory terms.

All relatives are grouped into three generations, with additional subdivisions along male and female lines. For men, one division is through the father’s line (including, for example, the husbands of the father’s mother’s sisters and the brothers of the mother’s mother), while the other is through the mother’s line (including the husbands of the mother’s mother’s sisters and the brothers of the father’s mother). Female divisions mirror this pattern. Grandparents and grandchildren are terminologically merged: each uses the same kinship term for the other, and members of the intervening generation likewise apply the same term to both.

Membership in a patrilineal moiety is lifelong and determines one’s ritual responsibilities and rights of access to particular territories. These rights are not ownership in the Western sense but involve obligations to participate in ceremonies, observe taboos, and care for ritually significant sites. Moiety membership also underpins hunting rights within a band’s territory, though outsiders may be granted temporary access.

Matrilineal moieties function mainly to define appropriate marriage partners. Since residence after marriage is patrilocal, a woman leaves her own section and lineage affiliation to join that of her husband.Male initiation traditionally involved a lengthy journey, often lasting several months, during which a young man traveled beyond his section’s territory and sometimes into contact with non-Kariera groups. This journey served multiple purposes: acquiring knowledge of surrounding lands, being gradually introduced into ritual lore, seeking a wife, and defining the “road”—the stretch of country in which he would live, travel, and hunt as an adult.

Martu

The Martu are a grouping of several Aboriginal Australian peoples in the Western Desert cultural bloc, which encompasses one-sixth of the continent of Australia. Also known as Mardu, Mardudjara, Jigalong, Martujarra and other names, they are notable for their social, cultural and linguistic homogeneity. "Martu" means "man" or "person,". It was coined as a collective label because there was no such traditional term. Constituent dialect-name groupings include the Gardujarra, Manyjilyjarra, Gurajarra, Giyajarra, and Budijarra. All Martu groups speak mutually intelligible dialects of the Western Desert language, the single-biggest Aboriginal language in Australia. There are currently several thousand speakers of this language. [Source: Robert Tonkinson, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

The traditional lands of the Martu are a large tract in the Great Sandy Desert, within the Pilbara region of Western Australia, including Jigalong, Telfer (Irramindi), the Warla (Percival Lakes), Karlamilyi (Rudall River) and Kumpupintil Lake areas. The Martu were granted native title to much of their country in 2002, after almost two decades of struggle It was geographically the largest claim in Australia to that time. However, Karlamilyi National Park was not included Martu land straddle the Tropic of Capricorn between 122° and 125° E in one of the world's harshest environments. Rainfall is very low and highly unpredictable. Permanent waters are rare, and both daily and seasonal temperature ranges are high (-4° C to over 54° C). Major landforms include: Parallel, red-colored sand ridges with flat interdunal corridors; stony and sandy plains (covered in spinifex); rugged hilly areas with narrow gorges; and acacia scrub thickets and creek beds lined with large eucalyptus trees.

The Martu population is estimated to be between 800 and 1,000 people, with some sources indicating a total population of around 2,500. Figures fluctuate due to the difficulties counting these remote people and who is and is not considered Martu. Today, most Martu reside in remote communities such as Jigalong, Parnngurr, Punmu, Kunawarritji although they still maintain access to their traditional lands. Many Martu live in the towns of Newman and Wiluna and areas nearby. It is impossible accurately to estimate the precontact populations of Martu. They were scattered in small bands (fifteen to twenty-five people) most of the time, and population densities were very low — about 1 person per 91 square kilometers. In the 1990s there were about 1,000 Martu, most of whom live either in the settlement of Jigalong or in a number of small outstation communities that have been established in the desert homelands within the past decade. Both the general population size and the ratio of Children to adults have grown greatly since migration from the desert.

See Separate Article: MARTU OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA: HISTORY, CUSTOMS, TRADITIONAL LIFE ioa.factsanddetails.com

Ngaatjatjarra

The Ngaatjatjarra are an Indigenous Australian people of Western Australia, with communities located in the north eastern part of the Goldfields-Esperance region. Also known as Ngatatjara Ngaayatjara, Ngadadjara, Pitjantjatjara and Western Desert Aboriginals, they speak the Warburton Ranges dialect of the Western Desert Language Group (Pitjantjatjara) in Western Australia and adjacent southwestern Northern Territory and northwestern South Australia. Their name for themselves, which means "those who have the word ngaata," which in turn means "middle distance," identifies the Warburton Ranges group in contrast with other, similarly identified dialect groups around them and does not imply any kind of tribal identity. [Source: Richard A. Gould, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

The population of Ngaanyatjarra people is estimated to be around 1,600 to 2,700, including those who those who reside permanently on Ngaanyatjarra Lands and those who visit the area. In the Ngaanyatjarra area of eastern Western Australia, approximately 2,000 to 2,300 Aboriginal people live across multiple communities, including some non-Ngaanyatjarra. The Ngaatjatjarra have traditionally been very mobile, which has made counting them difficult. Before the government resettled them in the late 1950s and early 1960s, many of these people followed a traditional nomadic hunting and gathering way of life, which dispersed them widely across the landscape. By 1970, the population at the Warburton Ranges Mission was around 400, and many Warburton people had moved elsewhere. |~|

The Pitjantjatjara language — to which the Ngaatjatjarra language or dialect belongs — is spoken in a wide area ranging from Kalgoorlie and Ceduna in Western Australia to the south and west, Ernabella and Musgrave Park in South Australia to the east, and Papunya and Areyonga in the Northern Territory to the north. Linguistic classifications currently accept Pitjantjatjara as part of the Wati subgroup of the Southwestern group of the Pama–Nyungan family, also called the Western Desert family. Most Ngaatjatjarra people are multilingual at the dialect level and often switch dialects when residing in new areas. The Western Desert linguistic family shares many features with other Aboriginal Australian languages.

The Warburton Ranges region is located at approximately 26° S and 127° E and includes rocky hills rising to an elevation of 700 meters (2,300 feet) above sea level and 300 meters (1,000 feet) above the surrounding terrain. Most of the surrounding area consists of sandhills, sand plains, and low laterite knolls. There is no permanent surface water, though relatively dependable water can be found by digging into dry creek beds and other specific locations. Weather records indicate that drought or semidrought conditions prevail in this region about half of the time, making it unsuitable for sustained European agriculture or pastoralism. |~|

See Separate Article: NGAATJATJARRA PEOPLE OF WEST-CENTRAL AUSTRALIA: HISTORY, CUSTOMS, TRADITIONAL LIFE ioa.factsanddetails.com

Pintupi

The Pintupi are an Australian Aboriginal group who are part of the Western Desert cultural group and speak a Pama-Nyungan language in the Western Desert Language Family. Their traditional land is in the area west of Lake Macdonald and Lake Mackay in Western Australia. They were hunters and gathers until relatively recently. Pintupi is not an indigenous term for a particular dialect nor for an autonomous community. The shared identity of these people derives not so much from linguistic or cultural practice but from a common experience and settlement during successive waves of eastward migrations out of their traditional homelands to the outskirts of White settlements.[Source: Nancy E. Gratton, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

The Pintupi population has not been precisely counted, but Joshua Project estimates a total of 1,400 Pintupi people in Australia, with a smaller group of 271 native Pintupi speakers reported in the 2021 census. Population figures for the Western Desert peoples as a whole are difficult to obtain. The sparsely populated Pintupi region, it has been estimated, can only support one person per 520 square kilometers, but given the highly mobile, flexible, and circumstance-dependent nature of the designation "Pintupi," absolute numbers are difficult to access.

The traditional territory of the Pintupi is located in the Gibson Desert in the Northern Territory of Australia. It is bordered by the Ehrenberg and Walter James ranges to the east and south, respectively; the plains west of Jupiter Wells to the west; and Lake Mackay to the north. The area is predominantly sandy desert interspersed with gravel plains and a few hills. The climate is arid; rainfall averages only 20 centimeters (8 inches) per year, and some years see no rainfall at all. Summer daytime temperatures reach about 50°C (122̊F), while nights are warm. Winter days are milder, but nights may be cold enough for frost to form.

Water is scarce, and vegetation is limited. Desert dunes support spinifex and a few mulga trees. On the gravel plains, there are occasional stands of desert oaks. Faunal resources are also limited. Large game animals include kangaroos, emus, and wallabies, while smaller animals include feral cats and rabbits. Water only periodically appears on the ground after it rains. People rely on rock and claypan caches in the hills, as well as underground soakages and wells in the gravel pan and sandy dunes. ~

See Separate Article: PINTUPI OF AUSTRALIA’S WESTERN DESERT: HISTORY, CUSTOMS, TRADITIONAL LIFE ioa.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Culture Shock! Australia, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated October 2025