Home | Category: Aboriginals

MARTU

Martu women from Parrnngurr, Punmu and Wiluna rest on a 'linyji' or pavement termitaria - as their forebears did generations before them; These women from Birriliburru and Kanyirninpa Jukurrpa Rangers had travelled to Kiwirrkura IPA to learn and share better ways to manage their desert country

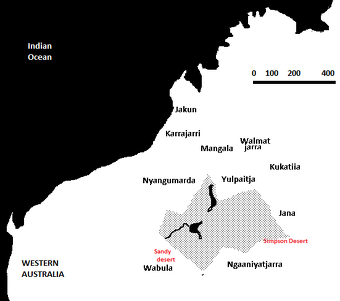

The Martu are a grouping of several Aboriginal Australian peoples in the Western Desert cultural bloc, which encompasses one-sixth of the continent of Australia. Also known as Mardu, Mardudjara, Jigalong, Martujarra and other names, they are notable for their social, cultural and linguistic homogeneity. "Martu" means "man" or "person,". It was coined as a collective label because there was no such traditional term. Constituent dialect-name groupings include the Gardujarra, Manyjilyjarra, Gurajarra, Giyajarra, and Budijarra. All Martu groups speak mutually intelligible dialects of the Western Desert language, the single-biggest Aboriginal language in Australia. There are currently several thousand speakers of this language. [Source: Robert Tonkinson, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

The traditional lands of the Martu are a large tract in the Great Sandy Desert, within the Pilbara region of Western Australia, including Jigalong, Telfer (Irramindi), the Warla (Percival Lakes), Karlamilyi (Rudall River) and Kumpupintil Lake areas. The Martu were granted native title to much of their country in 2002, after almost two decades of struggle It was geographically the largest claim in Australia to that time. However, Karlamilyi National Park was not included Martu land straddle the Tropic of Capricorn between 122° and 125° E in one of the world's harshest environments. Rainfall is very low and highly unpredictable. Permanent waters are rare, and both daily and seasonal temperature ranges are high (-4° C to over 54° C). Major landforms include: Parallel, red-colored sand ridges with flat interdunal corridors; stony and sandy plains (covered in spinifex); rugged hilly areas with narrow gorges; and acacia scrub thickets and creek beds lined with large eucalyptus trees.

The Martu population is estimated to be between 800 and 1,000 people, with some sources indicating a total population of around 2,500. Figures fluctuate due to the difficulties counting these remote people and who is and is not considered Martu. Today, most Martu reside in remote communities such as Jigalong, Parnngurr, Punmu, Kunawarritji although they still maintain access to their traditional lands. Many Martu live in the towns of Newman and Wiluna and areas nearby. It is impossible accurately to estimate the precontact populations of Martu. They were scattered in small bands (fifteen to twenty-five people) most of the time, and population densities were very low — about 1 person per 91 square kilometers. In the 1990s there were about 1,000 Martu, most of whom live either in the settlement of Jigalong or in a number of small outstation communities that have been established in the desert homelands within the past decade. Both the general population size and the ratio of Children to adults have grown greatly since migration from the desert.

RELATED ARTICLES:

ABORIGINALS (FIRST NATION PEOPLE) OF AUSTRALIA: NAMES, DEMOGRAPHICS, LANGUAGES ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS IN WESTERN AUSTRALIA: SOME GROUPS, HISTORY, CUSTOMS, TRADITIONAL LIFE ioa.factsanddetails.com

NGAATJATJARRA PEOPLE OF WEST-CENTRAL AUSTRALIA: HISTORY, CUSTOMS, TRADITIONAL LIFE ioa.factsanddetails.com

PINTUPI OF AUSTRALIA’S WESTERN DESERT: HISTORY, CUSTOMS, TRADITIONAL LIFE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS OF CENTRAL AUSTRALIA: SOME GROUPS, CUSTOMS, ART, LIFESTYLE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIANS IN NORTH NORTHERN TERRITORY: SOME GROUPS, CUSTOMS, LIFESTYLE ioa.factsanddetails.com

EARLY MODERN HUMANS IN AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

LIFE OF EARLIEST HUMANS IN AUSTRALIA: TOOLS, WEAPONS, ART, SETTLEMENTS ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINALS AT THE TIME EUROPEAN COLONIZATION BEGAN ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIA ABORIGINALS FROM 1900 TO PRESENT: DISCRIMINATION, ASSIMILATION, SOME RESTITUTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIA’S STOLEN GENERATIONS: VICTIMS, LAWS, RATIONALE, OUTRAGE ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL RELIGION: TRADITIONAL BELIEFS, DEMOGRAPHY AND DEATH ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL CUSTOMS, SOCIETY AND RITUALS ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL LIFE: WHERE THEY LIVE, WORK, DIET, HEALTH, ALCOHOL ioa.factsanddetails.com

TRADITIONAL ABORIGINAL LIFE: FOOD, HOMES, HUNTING ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL MEN AND WOMEN: GENDER, MARRIAGE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIAN SEX: PRACTICES, ATTITUDES, ADOLESCENCE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIAN ART ioa.factsanddetails.com

Martu History

The oldest known archaeological site on Martu land is Karnatukul (Serpent's Glen), located in Katjarra (Carnarvon Ranges). Charcoal from ancient campfires there has been dated to at least 50,000 years ago, meaning that humans have been there that long. Excavations have uncovered more than 25,000 stone tools and other artifacts, providing insights into the technologies and daily lives of these early inhabitants and the long-term, complex use of an arid landscape for tools, food, and medicine. The presence of wattle charcoal shows the plant's critical role as a source of firewood, food, and medicine for tens of thousands of years. Karnatukul is recognized as the earliest known occupation site in the Australian deserts, with research confirming early and repeated human occupation during various climatic shifts.

Protected by the harshness of their desert environment, the Martu remained relatively undisturbed by outsiders until the 20th century. Gradually, they were drawn from their homelands to the margins of white settlements — mining camps, pastoral stations, small towns, and missions. At first this occurred only for short stays, but growing demand for Aboriginal labor (and, in the case of women, sexual services), combined with a taste for European foods and goods, increasingly pulled the Martu into the orbit of the newcomers. Over time, they abandoned their nomadic hunting-and-gathering lifestyle in favor of a more sedentary existence near White settlements. This process began around 1900 and continued until as late as the 1960s. [Source: Robert Tonkinson, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

Despite these changes, the Martu remain among the more tradition-oriented Aboriginal peoples of Australia. Jigalong, originally founded as a maintenance camp on a rabbit-proof fence, became a ration depot in the 1930s for Aboriginal people gathering in the area. From 1946 to 1970 it operated as a Christian mission, though relations were often strained, and the Martu resisted attempts to suppress their traditions. Many Martu men and women also worked on surrounding pastoral leases as stockmen, laborers, or domestic workers. However, this employment declined dramatically after the 1960s introduction of laws requiring equal wages for Aboriginal and White workers in the pastoral industry.

In 1974, Jigalong was incorporated as an Aboriginal community, assisted by White advisers and supported largely through government funding. Since the early 1970s, government policy has officially promoted Aboriginal self-reliance and the preservation of cultural identity. Yet, for the Martu, increasing access to alcohol and wider pressures of Westernization have generated significant social problems that remain unresolved. One response to these pressures has been the establishment of outstations on or near traditional lands. These outstations not only aim to reduce the harms associated with alcohol but also represent a reassertion of ties to ancestral country. At the same time, the expansion of large-scale mining in the desert has provoked strong opposition from the Martu. Since the mid-1980s, through the formation of a regional land council, they have focused their efforts on protecting their lands from desecration and alienation.

Martu Religion

Religion, like kinship, pervades all aspects of Martu life. It is founded on the creative era now widely referred to as the Dreaming, when ancestral beings brought the world into existence and established the rules for living. Religion is expressed in the landscape itself, as well as in myths, rituals, songlines, and sacred objects. Life was understood to be under spiritual authority, though not through prayer or worship in the Western sense. Men guarded the most powerful inner secrets, and ritual performance was believed essential for the continuation of society, under the distant but watchful eyes of the ancestral beings. These beings were thought to release life force into the world only if “the Law”—their blueprint for proper social conduct—was faithfully observed through ritual. Totemism provided each individual with a personal and unique connection to the Dreaming and played a central role in shaping and sustaining identity. Almost all Martu take part in aspects of religious life, and while different ritual complexes assign different roles and grades, there are no professional religious specialists. [Source: Robert Tonkinson, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

The once-flourishing ceremonial life of the Martu, which traditionally involved all community members, now competes with many other distractions. Ceremonies are more seasonal, with most “big meetings” held during the very hot summer months. Some forms of ceremony are no longer performed, but those connected with male initiation remain central, often drawing several hundred Aboriginal participants from widely scattered communities. Ceremonial activities are still generally given precedence over sociopolitical concerns with the wider society. Traditionally, artistic expression was largely religious, involving the creation of sacred objects, body decorations, and ground paintings. For several decades, the production of weapons and artifacts for sale to outsiders has formed a minor, informal part of the local economy. In the 1990s, around 10 percent of Martu men were magician-curers (mabarn), part-time specialists who use magical means both to heal and, allegedly, to harm. The Martu also rely on a variety of bush medicines, while frequently turning to Western medical treatments as well. Belief in the efficacy and powers of mabarn and magic, however, remains strong.

Despite intensive contact with Europeans and a decline in the frequency of ceremonies, belief in the truth of the traditional religion remains strong. All young men continue to undergo initiation and to be entrusted with ritual knowledge. Belief in both benevolent and dangerous spirits is widespread, and Martu continue to fear traveling into unfamiliar country, where unknown spirits may pose a threat. A small minority identify as Christians, but even they do not reject traditional beliefs, and Christianity exists only as a partial overlay rather than a replacement.

Death and Afterlife” Martu death ceremonies were never highly elaborate. Their purpose is to guide the released spirit of the deceased back to the place it first emerged as a spirit child before entering its mother’s womb. Mourning is still marked by loud wailing, self-inflicted injury, and ceremonial exchange. Today, only a single burial takes place; the older practice of later exhuming bones for inquest and reburial has ceased. Mabarn (healers and ritual experts) attend burials to speak directly to the spirit, urging it to depart peacefully and not trouble the living. In some cases, Christian prayers are also recited. The Martu hold no belief in reincarnation.

Martu Marriage and Family

The main social unit was, and largely remains, the nuclear or polygynous family. Most people live near close relatives, with frequent visiting and shared meals across households. Generosity and sharing remain core values, and many households provide food and shelter for a shifting circle of relatives. [Source: Robert Tonkinson, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

Classificatory bilateral cross-cousin marriage have traditionally been the norm. Such marriages are when an individual is expected to marry a person who is a cross-cousin on both the mother's and father's side simultaneously, and typically is a symmetrical exchange between two kinship groups. This system involves a broad, "classificatory" application of kinship terms, where many individuals are considered to be cross-cousins, making the potential pool of marriage partners larger. The practice functions as a cultural mechanism to foster alliances and maintain resources within a wider alliance system.

Polygyny was upheld as a social ideal, though not always realized, and while it continues today, it is no longer common. Infant betrothal was once common. All adults were expected to marry, widows remarried, and divorce was rare. In contrast, many widows now remain single, and young unmarried mothers are common. Although marriage rules are less strictly followed, they still retain considerable force, and transgressors may be physically punished. Traditionally, men were prohibited from marrying for at least a decade after their first initiatory rites, which occurred around ages 16–17. Today, marriages often take place in the early twenties, and fewer betrothals are carried through to marriage.

Infants and children are raised collectively by parents, siblings, and coresident kin, with grandparents playing a central role. Children are generally indulged by adults and can obtain food and money from a wide network of relatives. Exempt from observing kinship rules, they spend much of their time in large play groups. Traditionally, children—especially girls—spent considerable time with women, accompanying them on food-gathering trips. Today, most children attend school from age 5 or 6, though attendance is often irregular. From the teenage years onward, gender roles diverge sharply. Girls transition into wives and mothers without ritual, while boys undergo a protracted and ritually elaborate initiation sequence lasting about 15 years, from the first physical operations (such as nose piercing) to the final stages before first marriage. Marriage in the late twenties marks the young man’s social adulthood.

In regard to Inheritance, in the past, material possessions were few and typically buried with the deceased. Today, they are more often burned or distributed to distant relatives, while houses or camps associated with the deceased are abandoned for months or even years.

Martu Life and Economic Activity

Today, most Martu live in Jigalong or smaller outstations on the western side of the Gibson Desert. A few, mostly steady drinkers, live in or on the fringes of regional towns. Mobility remains high, especially between Jigalong, which has a population of around 300, and the outstations, which have populations ranging from 20 to 100 people. Jigalong has an airfield and graded dirt roads that connect it to the main highway to the west. The town also has telephone and radio contact, television, and many motor vehicles. The town has a large school, a medical clinic, a sewage system, an electricity and water supply, a well-stocked community store, and many European-style houses for white staff and Aboriginal people. However, many people still live in squalid and unhygienic conditions. The outstations are still being developed but have basic necessities, such as a water supply and radio transceivers. The larger outstations have an airfield, a school, electricity generators, and refrigeration. [Source: Robert Tonkinson, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

The traditional hunting and gathering economy, which was completely autonomous, and pastoral employment, which was partially self-sufficient, have been replaced by massive unemployment and a highly dependent, welfare-based existence. The Martu region is ecologically marginal, so developing profitable local land-based industries is unlikely. Jigalong operates a cattle enterprise, and various other economic initiatives have been attempted without success. Despite the continuation of hunting and gathering activities, all the settlements heavily rely on imported food. In Jigalong, the large settlement economy provides salaried work for Aboriginal office and store workers, teachers, health aides, maintenance workers, and pastoral employees. Besides kinship, card gambling is an important means of redistributing cash. Aboriginals have adopted many material items from whites, but they have strongly resisted changes in basic values relating to kinship and religion. |~|

Although formalized trading networks were absent in the Western Desert, scarce and highly valued items such as pearl shells and red ocher diffused widely throughout the region as a result of exchanges between individuals and groups, mostly in the context of ceremonial activities. Group exchanges centered on religious lore, both material and nonmaterial. The exchange of mundane material items, such as weapons or tools, clearly took a backseat to religious concerns. Most individual transactions were gift exchanges conducted within the framework of kinship and marital obligations. |~|

The traditional gender-based division of labor, with women as gatherers (and hunters of small game) and men as hunters, continues to be observed but is no longer central to subsistence. Traditionally, the diet was based on kangaroos, emus, lizards, birds, insects, and grubs, along with grass seeds, tubers, berries, fruits, and nectars. Today, women remain the primary cooks, housekeepers, and office workers, while men generally prefer outdoor work. Children usually remain in school through their mid-teens, limiting their economic contribution. However, girls still tend to marry earlier than boys and assume full parental responsibilities at a younger age.

Martu Kinship and Land Tenure

Although traditional local organization and dispersal have given way to aggregation in sedentary communities, kinship remains a fundamental building block of Martu society. Everyone relates to one another primarily in terms of kinship norms. Kinship and religious ties connect Aboriginal people across the vast Western Desert. The Martu are drawn from territorial divisions named after their dialects that unite territory, language, and kin groups. These larger units, sometimes incorrectly called "tribes," never existed as corporate entities. Though boundaries existed, they were highly permeable. [Source: Robert Tonkinson, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

The most visible group was the band, whose camping arrangements reflected the family groups that made up this flexible aggregation. Within every dialect-named area were a number of bands and at least one "estate," which was the highly valued heartland containing major sacred sites, important waterholes, and the locus of the estate group. The Martu kinship system is bilateral; however, there was traditionally a clear patrilocal tendency in residence rules and practices, as well as a strong preference for children to be born somewhere in or near their father's estate. Both the estate group and the band tended to have a core of people who were related patrilineally (based on descent through the male line). There were no lineages or clans, and genealogical depth was limited (aided by taboos on naming the dead).

Kinship Terminology is bifurcate-merging and occurs in association with a section system, with the division of society into four named categories. Bifurcate merging, also known as Iroquois kinship, is a system of kinship that distinguishes between same-sex and cross-sex parental siblings, as well as gender and generation. The brothers of an individual’s father and the sisters of an individual’s mother are referred to by the same parental kinship terms used for father and mother. The sisters of the individual’s father and the brothers of the individual’s mother, on the other hand, are referred to by non-parental kinship terms commonly translated as "aunt" and "uncle." The children of one's parents' same-sex siblings—i.e., parallel cousins (children of a father’s brother or a mother’s sister)—are referred to by sibling kinship terms. The children of aunts or uncles (cross cousins, or two cousins who are children of a brother and sister) are not considered siblings and are referred to by kinship terms commonly translated as "cousin." [Source: Wikipedia]

Of the seventeen different terms of address used by each sex, many are shared by male and female speakers. Martu also employ a large and complex set of dual-reference terms. There is a generational emphasis; for example, all people in one's grandparent and grandchild generations are merged under two nearly identical terms that differ only by the person's sex. Behavior patterns associated with each kin term range along a continuum from joking to avoidance.

Traditionally, bands were the basic land-occupying economic unit, while large, territorially anchored entities known as estate groups were associated with land ownership. Although these groups contained a core of patrilineal males related by descent through the male line, they had multiple membership criteria, and active adults could be significantly involved in more than one group. Since land was inalienable, property rights were more often conceptualized in terms of responsibility for sites and resources rather than control over them. Martu society strongly favored inclusivity and maximizing rights and obligations in both ethos and practice. Today, the Jigalong area is an officially recognized Aboriginal reserve, yet the Martu have yet to obtain firm tenure to their traditional homelands.

Martu Social and Political Organizations

Traditionally, families, bands, estate groups, and "big meetings" (periodic gatherings of people from neighboring territories who met to conduct rituals and other business) were the main elements of social organization. These groups were interconnected by various memberships, including totemic, kin-based, and ritual-grade, among others. These memberships, including moieties and sections, were integral to desert society. Today, families and "big meetings" remain important institutions, but they coexist with introduced forms, such as committees and councils. ~[Source: Robert Tonkinson, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

In the past, political action was the domain of small groups, and sex and age were the primary criteria for differentiation. Although women had a lower status than men, an egalitarian ethos prevailed, and leadership depended heavily on context and was changeable. Most of the time, the norms of kinship provided an adequate framework for social action and role allocation. The social and political autonomy of traditional bands and estates has been replaced by encapsulation and minority status within nation-states, as well as the introduction of Western-style institutions, such as elections and councils. High mobility and involvement in regional land councils reflect the Martu's continuing interest in the wider Western Desert Society as "one people." They spend much time and effort maintaining these contacts. Politically, the Martu depend on the government for survival and on white advisers for help navigating the bureaucracies of Australian society. In recent years, however, there has been a notable increase in Martu political awareness and confidence when interacting with outsiders. |~|

Traditional social controls relied heavily on self-regulation, though physical sanctions were occasionally invoked. Western influences have seriously undermined these controls in situations of contact. Spearing and other forms of physical punishment, for example, have led to police intervention and the arrest of those administering "lawful" punishments. Unprecedented numbers of children have resulted in vandalism problems, and there has been an increase in marriages between improperly related partners. Young women have also successfully resisted attempts to marry them off to their betrothed partners. Alcohol has greatly contributed to the loosening of traditional social controls, and uncontrolled violence (as well as drunk driving) has resulted in numerous fatalities.|~|

Traditionally, conflict was closely controlled, and ritualized dispute resolution was a vital preliminary to every "big meeting." Today, in addition to these more difficult-to-control internal conflicts, there are political struggles with mining companies and a neighboring Aboriginal group that has long unsuccessfully sought to control the Martu.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Kanyirninpa Jukurrpa

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Culture Shock! Australia, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated October 2025