Home | Category: Aboriginals / Arts, Culture, Media

ABORIGINAL ART FROM NORTHERN AUSTRALIA

Northern Australia is most famous for its rock paintings and bark paintings. Some of the rock art there may be 40,000 years old. The art from North Australia is more literal than art from Central Australia. It often contain images of people and animals whose meanings ar widely understood.

For tens of thousands of years, Aboriginal peoples have used art to record and share their stories of creation, culture, and ceremony. Across the north of the Northern Territory, ocher paintings, rock carvings, weaving, wood sculptures, screen-printed textiles, bark paintings, and decorated ceremonial objects remain central forms of expression, showcased today in art centres, galleries, and national parks.

From the vivid palettes of Utopia artists, to the luminous watercolours of Albert Namatjira depicting the landscapes of Hermannsburg, to the distinctive X-ray animal paintings of the Top End, Aboriginal art embodies both purity and cultural depth. Without words or sound, it transcends language and dialect to communicate story and meaning, offering profound insight into Aboriginal culture and heritage.

Hollowed-out logs used in reburial ceremonials among the Aboriginals of Arnhem Land were often elaborately decorated. The Marramunga people of the Murchinson Range of Northern Territory make ground painting of the great snake Wollonqua, who the Marramunga say was so enormous he could travel far and wide while his tail remained in the waterhole from which it originated.

RELATED ARTICLES:

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIAN ART ioa.factsanddetails.com

VERY, VERY OLD AUSTRALIAN AND ABORIGINAL ROCK ART ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL PAINTINGS ioa.factsanddetails.com

MODERN AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL ART: PAPUNYA, MANGKAJA, REDISCOVERY, REVIVAL, AND A NEW AUDIENCE ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL ART FROM DIFFERENT REGIONS ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL ART FROM QUEENSLAND AND THE TORRES STRAIT ioa.factsanddetails.com

WELL-KNOWN ABORIGINAL ARTISTS: THEIR LIVES, WORKS AND IMPACTS ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS (FIRST NATION PEOPLE) OF AUSTRALIA: NAMES, DEMOGRAPHICS, LANGUAGES ioa.factsanddetails.com

EARLY MODERN HUMANS IN AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

LIFE OF EARLIEST HUMANS IN AUSTRALIA: TOOLS, WEAPONS, ART, SETTLEMENTS ioa.factsanddetails.com

PEOPLE WHO LIVED AUSTRALIA 20,000 TO 10,000 YEARS AGO ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

RITUAL LIFE AND MYTHS OF ANCIENT AUSTRALIANS ioa.factsanddetails.com

EARLY ABORIGINALS ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINALS AT THE TIME EUROPEAN COLONIZATION BEGAN ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIA ABORIGINALS FROM 1900 TO PRESENT: DISCRIMINATION, ASSIMILATION, SOME RESTITUTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIA’S STOLEN GENERATIONS: VICTIMS, LAWS, RATIONALE, OUTRAGE ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL RELIGION: TRADITIONAL BELIEFS, DEMOGRAPHY AND DEATH ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL CUSTOMS, SOCIETY AND RITUALS ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL LIFE: WHERE THEY LIVE, WORK, DIET, HEALTH, ALCOHOL ioa.factsanddetails.com

TRADITIONAL ABORIGINAL LIFE: FOOD, HOMES, HUNTING ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL MEN AND WOMEN: GENDER, MARRIAGE, SEX ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIAN SEX: PRACTICES, ATTITUDES, ADOLESCENCE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS IN QUEENSLAND: SOME GROUPS, CUSTOMS, LIFESTYLES ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIANS IN NORTH NORTHERN TERRITORY: SOME GROUPS, CUSTOMS, LIFESTYLE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS OF CENTRAL AUSTRALIA: SOME GROUPS, CUSTOMS, ART, LIFESTYLE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS IN WESTERN AUSTRALIA: SOME GROUPS, HISTORY, CUSTOMS, TRADITIONAL LIFE ioa.factsanddetails.com

Rock Art from Northern Australia

The oldest reliably dated rock art scenes in Australia are found in Arnhem Land in northern Australia and consist of animals sketched in charcoal that has been radiocarbon dated to about 30,000 B.C. Matt Stirn wrote in Archaeology Magazine: Beginning with those very first depictions, rock art in Arnhem Land has provided insight into aspects of past ways of life that are not obvious through archaeological excavations. These include techniques for hunting with boomerangs and the process by which fish were caught and cleaned. Beyond offering a vibrant view of Arnhem Land’s deep past, the continuous evolution of rock art in the region has also allowed researchers to develop a chronology based on style and content. Such an investigation has required meticulous identification of the tens of thousands of figures and scenes that, in many instances, were drawn on top of one another. [Source: Matt Stirn, Archaeology Magazine, May/June 2021]

rock art areas in Northern Territory, Australia, Archaeology magazine

Margaret Grove wrote in Archaeology magazine: Across the warm, weathered sandstone of the northern Australian coast, extinct Tasmanian tigers prowl and hippopotamus-like marsupials graze, bright blue dingoes playfully wrestle, giant cranes gather at sacred breeding grounds, and ceremonial figures — humans with attributes of animal and insect bodies — engage in exotic rituals. These are among the region's thousands of paintings, some created over 50,000 years ago, others as recently as the 1950s. Archaeological science finds them difficult to date with confidence or precision. [Source: Margaret Grove, Archaeology magazine Volume 55 Number 5, September/October 2002' Margaret Grove has done rock-art research in Australia for many years. She is an associate professor of women's spirituality at New College of California in San Francisco, where she teaches Archaeomythology, a combination of archaeology and oral traditions.

The north Australian terrain, created by Ancestor Beings eons ago during what the Aboriginal people know as the Dreamtime, is so rugged that many sites remain unknown to outsiders. Nonetheless, new discoveries, Aboriginal landowners accompany researchers on explorations by foot, four-wheel drive, or helicopter. The research season in 2001 yielded 24 new sites in less than a week.

Jowallabina, in the Laura sandstone area, contains one of the largest collect of rock art in the world, some of it over 32,000 years old. It is located on the Cape York Peninsula, one of the world's last great untamed wildernesses. Covering 54,000 square miles (about the same size as Michigan) and described by many Australian simply as the Tip, it is the northernmost extension of the of the Australian mainland, jutting northward within a 100 miles of New Guinea. The major exploration of this art was undertaken over past thirty years by Percy Tresize, a well-known north Queenslander and author.

The Marra Wonga rock shelter in central Queenslandsite contains 15,000 petroglyphs created over thousands of years. Researchers learned that one of the main scenes, which includes starlike designs, snake figures, and human feet, tells the Aboriginal Dreaming story of the Seven Sisters. According to the tale, an Ancestral Being known as Wattanuri pursued the sisters across the Australian landscape, and their altercations led to the creation of many prominent features existing today.[Source: Archaeology magazine, January 2023]

Related Articles:

VERY, VERY OLD AUSTRALIAN AND ABORIGINAL ROCK ART ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

RITUAL LIFE AND MYTHS OF ANCIENT AUSTRALIANS ioa.factsanddetails.com

LIFE OF EARLIEST HUMANS IN AUSTRALIA: TOOLS, WEAPONS, ART, SETTLEMENTS ioa.factsanddetails.com

PEOPLE WHO LIVED AUSTRALIA 20,000 TO 10,000 YEARS AGO ioa.factsanddetails.com

Arnhem Land Rock Art

The rocky landscape of West Arnhem Land is home to thousands of years of rock art and thousands of painting created by Aboriginal people. Ancient paintings revealed in 2020 depict close relationships between humans and animals The Smithsonian reported: Kangaroos and wallabies mingle with humans, or sit facing forward as if playing the piano. Humans wear headdresses in a variety of styles and are frequently seen holding snakes.“We came across some curious paintings that are unlike anything we’d seen before,” Paul S.C. Taçon, lead author of a study published in the journal Australian Archaeology, told the BBC.[Source: Livia Gershon, Smithsonian magazine, October 5, 2020]

Matt Stirn wrote in Archaeology Magazine: Along the northern coast of Australia’s Arnhem Land, the Alligator Rivers wind among towering sandstone outcrops, forming a maze of estuaries that eventually empty into the Timor Sea. Kangaroos hop alongside fish-filled rivers, through tropical savannas, and into thick forests of eucalyptus where dingoes, lizards, wallabies, pythons, and more than 100 species of birds make their home. Entwined with the natural landscape, evocative images of both animals and people painted on rocky crags and inside shallow caves appear as evidence of the region’s human past. West Arnhem Land is home to one of the world’s largest collections of rock art, a testament to the relationship between humans and nature that has thrived here since the Paleolithic era, more than 30,000 years ago. The region remains one of the most pristine and protected wilderness areas on the continent. Today, Arnhem Land is owned and managed by the nearly 12,000 Aboriginal people who call it their home, and whose vital contemporary culture is interwoven with the continent’s richest and longest archaeological record. This landscape is one of the only places in the world where modern Indigenous communities have maintained a millennia-old rock art tradition, preserving a storytelling practice that speaks of their history and culture, and of changes to the earth. [Source: Matt Stirn, Archaeology Magazine, May/June 2021]

Collaborating closely with the area’s Aboriginal communities over more than a decade, the researchers recorded 572 paintings at 87 sites across an 80-mile area in the far north of Australia, write Taçon and co-author Sally K. May in the Conversation. The area is home to many styles of Aboriginal art from different time periods. Most of the red-hued, naturalistic drawings are more than 2.5 feet tall; some are actually life-size. Dated to between 6,000 and 9,400 years ago, many depict relationships between humans and animals — particularly kangaroos and wallabies. In some, the animals appear to be participating in or watching human activities. One painting shows two humans — a man with a cone-and-feather headdress and another holding a large snake by the tail — holding hands.

Taçon told Australian Archaeology: “Such scenes are rare in early rock art, not just in Australia but worldwide,” explain Taçon and May in the Conversation. “They provide a remarkable glimpse into past Aboriginal life and cultural beliefs.” Taçon told the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) that the art appears to be a “missing link” between two styles of Aboriginal art found in the area: dynamic figures and X-ray paintings.The newly detailed works also share some features with X-ray paintings, which first appeared around 4,000 years ago. This artistic style used fine lines and multiple colors to show details, particularly of internal organs and bone structures, according to the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

In addition to offering insights on the region’s cultural and artistic development, the figures also hold clues to changes in the area’s landscape and ecosystems. The archaeologists were particularly interested in pictures that appear to depict bilbies, or small, burrowing marsupials. “Bilbies are not known from Arnhem Land in historic times but we think these paintings are between 6,000 and 9,400 years of age,” Taçon tells the ABC. “At that time the coast was much further north, the climate was more arid and ... like what it is now in the south where bilbies still exist.” This shift in climate occurred around the time the Maliwala Figures were made, the researcher tells BBC News. He adds, “There was global warming, sea levels rising, so it was a period of change for these people. And rock art may be associated with telling some of the stories of change and also trying to come to grip with it.”

The art also includes the earliest known image of a dugong, or manatee-like marine mammal. “It indicates a Maliwawa artist visited the coast, but the lack of other saltwater fauna may suggest this was not a frequent occurrence,” May tells Cosmos magazine’s Amelia Nichele. Per Cosmos, animals feature heavily in much of the art. Whereas 89 percent of known dynamic figures are human, only 42 percent of the Maliwawa Figures depict people.

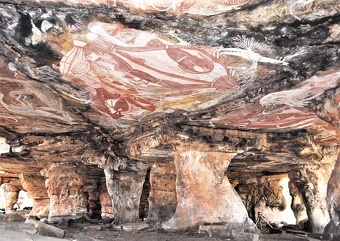

Kakadu Aboriginal Art

Kakadu National Park (200 kilometers, 125 miles, east of Darwin) is a great place for viewing Aboriginal rock art. Declared a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1981 it is a 1,200 square mile park encompassing all of northern Australia's major habitats-coastal fringe, woodlands, plateaus, rain forests, hills, wetlands and waterways. Kakadu abuts against the Aboriginal homeland of Arnhem Land, which occupies a large chunk of land along north Australia coast. In the 1.6 billion year old sandstone escarpments that run through the park are 7,000 rock-art sites, some of which contain paintings that are believed to be 35,000 years old. Some are paintings. Some are engravings. Others designs in wax.

The rock paintings are sacred to Aboriginals. Many of the ocher and white clay images in the paintings depict "dreamtime" figures, specific gods are usually put in places they believe that god dwells. Most of these sites are natural landmarks, like sandstone rock formation with a feature that recalls something about a dreamtime spirit. These sites are visited over and over through time by generations of Aboriginal who renew themselves spiritually and maintain their bond with their gods and nature with each visit. Many of the painting are not paintings at all, the Aboriginal believe, but are images that have been placed where they are by the gods.

Marley Brown wrote in Archaeology magazine: Kakadu “is one of the greatest rock-art landscapes in the world. Recent archaeological excavations have pushed back the earliest dates of human presence in the region to around 65,000 years ago. More than 5,000 sites with petroglyphs have been recorded within the park’s 8,000 square miles. Pinning down the precise date of some of Kakadu’s rock art is challenging, as many of the mineral pigments used in the area are not datable using radiocarbon methods. Therefore, says Samantha McLean of Kakadu’s research and permits office, archaeologists and art historians have constructed timelines for the art using a combination of thermoluminescence dating, which can determine when mineral elements of paint or ceramics were first heated or fired, and representations of flora and fauna, which have changed over time along with the climate. [Source: Marley Brown, Archaeology magazine, May-June 2019]

Some of the most stunning images in Kakadu are found on or near Nourlangie Rock, a massive sandstone formation about a half-hour drive south from Jabiru, the park’s largest hub, which has facilities such as hotels and welcome centers. Another of the rock art sites, called Nanguluwur, was used as a campsite by ancestors of the Bininj/Mungguy people for millennia, and features an array of paintings and hand stencils ranging from several thousand to fewer than 100 years old. “Here you can see powerful depictions of ancestral spirits, animals, as well as fascinating early illustrations of contact between Aboriginal people and Europeans,” says McLean.

Three main areas are open to the public. The most well known are Ubirr and Nourlangie, which are more than 2,000 years old. The guides and rangers that escort visitors to the paintings are Aborigines, who can tell you about their meaning and significance. Unfortunately most of the older sites are closed to visitors. Many of those that are open have painting made in the last fifty years and recently touched up. Ubirr is 42 kilometers (28 miles) from the Arhem Highway. There is a one mile path at Ubirr with painting on several rocks along the route. The main attraction is the main gallery, which has excellent paintings of goannas, wallabies, fish, kangaroos and even white men. There is a famous painting of the Rainbow serpent and the Namakan Sisters.

Dampier Rock Art Complex

Dampier Rock Art Complex is situated on the northwestern coast of Australia, and contains over 500,000 rock carvings. Laura Helmuth wrote in Smithsonian magazine: The Dampier Islands weren't always islands. When people first occupied this part of western Australia some 30,000 years ago, they were the tops of volcanic mountains 60 miles inland. It must have been an impressive mountain range back then — offering tree-shaded areas and pools of water that probably drew Aborigine visitors from the surrounding plains.

rock art from Murujuga in Western Australia that includes art from the Burrup Peninsula and Dampier Archipelago

No one knows when people first started scraping and carving designs into the black rocks here, but archaeologists estimate that some of the symbols were etched 20,000 years ago. As far as the scientists can tell, the site has been visited and ornamented ever since, even as sea levels rose and turned the mountains into a 42-island archipelago. Today 500,000 to one million petroglyphs can be seen here — depicting kangaroos, emus and hunters carrying boomerangs — constituting one of the greatest collections of rock art in the world. [Source: Laura Helmuth, Smithsonian magazine, March 2009]

The oldest petroglyphs are disembodied heads — reminiscent of modern smiley faces but with owl-like eyes. The meaning of these and other older engravings depicting geometric patterns remains a mystery. But the slightly younger petroglyphs, depicting land animals from about 10,000 years ago, lend themselves to easier speculation. As with most art created by ancient hunting cultures, many of the featured species tend to be delicious. Some of the more haunting petroglyphs show Tasmanian tigers, which went extinct there more than 3,000 years ago. When the sea levels stopped rising, about 6,000 years ago, the petroglyphs began to reflect the new environment: crabs, fish and dugongs (a cousin of the manatee).

Interspersed among the petroglyphs are the remains of campsites, quarries and piles of discarded shells from 4,000-year-old feasts. As mountains and then as islands, this area was clearly used for ceremonial purposes, and modern Aborigines still sing songs and tell stories about the Dampier images.

Archaeologists started documenting the petroglyphs in the 1960s and by the 1970s were recommending limits on nearby industrial development. Some rock art areas gained protection under the Aboriginal Heritage Act in the 1980s, but it wasn't until 2007 that the entire site was added to Australia's National Heritage List of "natural and cultural places of outstanding heritage value to the nation."

"The art and archaeology of the Dampier Archipelago potentially enable us to look at the characteristics of our own species as it spread for the first time into a new continent," says archaeologist Sylvia Hallam, and to study how people adapted to new landscapes as sea levels rose. But there's also meaning in the sheer artistry of the place. The petroglyphs, Hallam adds, allow us "to appreciate our capacity for symbolic activity — ritual, drama, myth, dance, art — as part of what it means to be human." Tourists are still welcome to explore the rock art freely, and talks are in progress to build a visitor center.

Maliwawa Style Rock Art of West Arnhem Land

The Maliwawa style is a fairly recently discovered and named art-style found on rock walls in Australia’s West Arnhem Land. The images depict floating human forms in a time known as the Dreaming, an era in Aboriginal beliefs associated with creation. Much of this art has been dated to between 8000 and 4000 B.C. For a long time archaeologists had difficulty finding art from this period although they could find a fair amount before and after that time. Ronald Lamilami, and archaeologist and senior traditional landowner and Namunidjbuk elder, named the artworks the “Maliwawa Figures” in reference to a part of the clan estate where many were found. Maliwawa is a word in the Aboriginal Mawng language. [Source: Matt Stirn, Archaeology Magazine, May/June 2021]

Matt Stirn wrote in Archaeology Magazine: During an eight-year survey of rock art near West Arnhem Land’s Wellington Range, Tacon’s team made a startling discovery: rock art panels depicting large humans and animals in poses and in relationship to each other that were unlike anything they had seen before, despite decades of fieldwork in the region and nearly 80 years of other research efforts preceding theirs. As the team continued surveying sites spread over 80 miles, they identified 572 Maliwawa Style figures. “It was really exciting to find previously undocumented shelters with lots of Maliwawa figures on walls and ceilings, sometimes in scenes,” Tacon says. “When we saw these paintings for the first time, there was a rush of adrenaline, much excitement, cheering, and lots of shouts to each other.” [Source: Matt Stirn, Archaeology Magazine, May/June 2021]

Painted in red and mulberry ocher with stroke-line infill, a technique in which artists fill in the interior of figures with parallel lines, the oversize Maliwawa Style figures showcase people in dreamlike floating poses, human figures with kangaroo heads, and an extraordinary variety of animals, including snakes, kangaroos, birds, desert-dwelling marsupials called bilbies or bandicoots, marine mammals related to manatees called dugongs, and thylacines, or Tasmanian tigers, which went extinct on the Australian mainland around 2,000 years ago. In many scenes that emphasize the relationship between people and animals, the animals seem to be the focus and appear as if they are watching the human figures. In one particular scene, a man wearing a headdress reaches out to an emu-like bird on his left and a half-human, half-kangaroo creature on his right. “This arrangement suggests transformation from kangaroo to human, a feature of many works of art documented in West Arnhem Land,” says Tacon. “Human-animal connectedness is represented here in a very strong way.” In addition to offering a distinctive perspective on human relationships with nature, some of the newly identified Maliwawa Style scenes appear on top of Dynamic Style figures and under Simple Figures Style drawings, perfectly filling in the 4,000-year gap in West Arnhem Land’s artistic history. At long last, archaeologists could learn more about life in this part of Australia between 8000 and 4000 B.C.

In addition to documenting people’s observations of animals encountered in the natural world, Maliwawa Style rock art depicts scenes related to the spiritual realm. Bininj Aboriginal elder Thompson Yulidjirri shared with the team that, in Arnhem Land, “art is not an end, but a gateway.” In this sense, it offers a venue to connect with spiritual beliefs, and in the case of the Maliwawa Style, to take viewers to the very beginning of time. During field surveys on which they accompanied Tacon and his team, several Aboriginal collaborators recognized that many of the Maliwawa Style scenes composed of floating people and human-animal hybrids represent depictions of the Dreaming, a period in Aboriginal belief systems when the world was created and spirits passed on information and values through art. “Some Maliwawa Style scenes seem to depict important Dreaming creation stories that are still important today,” says Tacon, “and aspects of the style, such as the back-to-back figures, are still painted in the context of important spirit beings. So the Maliwawa Style figures highlight long-term connections not only to the land, but also to the origin of key creation stories in a time of great change.” Some supernatural aspects of the scenes may relate to the dramatic shifts in the landscape and reflect a spiritual interpretation of a new physical world that was coming into being in Arnhem Land as a result of climatic events.

Maliwawa Style Rock Art and Climate Change

Matt Stirn wrote in Archaeology Magazine: When the earliest Maliwawa Style scenes were painted around 10,000 years ago, northern Australia was in the midst of a period when its climate and weather patterns were shifting. “The time of the Maliwawa Style scenes was one of transformation, with landscapes responding to climate change at the tail end of the last Ice Age and developing warmer and wetter conditions,” says Cassandra Rowe, a paleoclimatologist from James Cook University who has worked extensively in West Arnhem Land. From about 12,000 until 6000 B.C., the sea level increased rapidly and the coastline retreated up to 150 feet each year. As salt water encroached on the land, newly formed mangrove forests grew inland, and increased rainfall fed already swollen rivers. [Source: Matt Stirn, Archaeology Magazine, May/June 2021]

During this time, Maliwawa Style painters likely experienced unexpected interactions with animals that were venturing out of their typical ranges due to the changing conditions. A depiction of a dugong—the earliest known image of the species—possibly dates to a time when high sea levels would have allowed the animals to venture much farther upriver than would be possible today. Similarly, the prevalence of snakes in Maliwawa Style scenes might be explained by greatly increased rainfall and encroaching salt water pushing the reptiles out of their holes and into more frequent encounters with people. Unlike many styles of rock art that portray events through a human-centric view, the Maliwawa Style depictions of interactions between animals and people from the animals’ perspective reveal a subtle yet powerful message, as if suggesting that every living thing in West Arnhem Land was equally impacted by the transforming world.

As the sea level began to stabilize around 5000 B.C. and increasingly frequent monsoons unleashed even more precipitation on Arnhem Land, the mangroves retreated and a mixed landscape of freshwater and saltwater environments formed near the coast. At the same time, a combination of savanna and forest developed farther inland. Beginning around 4300 B.C., the region experienced an arid period of decreased precipitation before settling into the subtropical climate it has today around 2000 B.C. The portrayal of several bilbies in Maliwawa Style scenes—the earliest known appearance of these mammals in the art of Arnhem Land—may correspond to the end of the style, when the landscape briefly became drier and allowed new animals to venture into the region.

While the many changes to the landscape following the Ice Age would have put pressure on the people of Arnhem Land, the transition also provided new opportunities. Rock art dating to a time just prior to the development of the Maliwawa Style depicts a noticeable shift from people using terrestrial to estuarine resources as they adapted to new environments. The identification of shell middens in the archaeological record further supports the idea that people relied on estuarine and floodplain resources throughout the period. Just as animals and ecosystems were pushed inland during the time when the Maliwawa Style paintings were made, so were people. Prior to 8000 B.C., rock art in Arnhem Land developed in a stylistically consistent way across the entire region. But after the climate changed and people moved farther inland and led less mobile lives, local styles began to develop. “Populations were becoming more regionally distinct, and this can be seen in the rock art across West Arnhem Land,” says Tacon. “The emergence of a few regionally distinct styles of rock art in northern Australia, including the Maliwawa Style, reflects this.” By the time the last Maliwawa Style figures were painted around 4000 B.C., people’s way of life in Arnhem Land had been dramatically altered. These changes were reflected in rock art, and also may have inspired some Aboriginal creation stories that are still told today, 6,000 years later.

Bark Painting from Northern Australia

Bark paintings are relatively new art forms. There is no evidence of bark paintings before the late 19th century (they may have existed before then but nothing remains because bark deteriorates easily). Tourism has created a large demand for bark paintings. In the old days wax, plant resins and yolks from the eggs of wild birds were used as bonding agents and brushes were made from feathers, hair and leaf fibers. These days synthetic agents or wood glues are mostly used and brushed are the same as those bought by artists at art supply stores.

The bark used in bark painting comes the stringybark tree, a kind of eucalyptus. The bark is removed from the tree during the wet season when it is moist. The rough outer later is taken off and the inner bark is dried over a fire and pressed under weighs. All this takes about two weeks. Most bark paintings have a stick across the top and bottom to keep the bark flat. Most of the pigments are white (kaolin), black (charcoal) and red and yellow (ochers) because they were the same pigments used in body and rock painting.

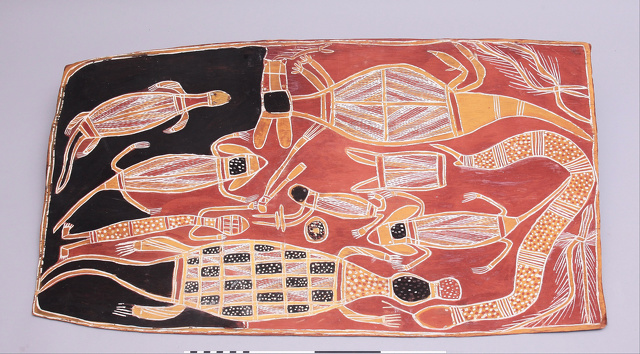

Eric Kjellgren wrote: The bark paintings of northern Australia are one of the continent's most distinguished art forms. Although bark paintings are created in other areas, the most prolific bark painters are the peoples of the vast region of Arnhem Land and the islands off its shores. Sharing techniques, pigments, and iconography with the region's ancient rock art traditions, Arnhem Land bark paintings are rendered in ocher and other natural pigments on canvases made from fibrous sheets of bark peeled from the trunks of "stringybark" trees.'

The stark black background of the present painting is characteristic of mid-twentieth-century works by the lngura people of Groote Eylandt, a large island that lies off Arnhem Land 's northeastern coast. As elsewhere in Arnhem Land, the contemporary barkpainting tradition on Groote Eylandt likely had its origin in the paintings made on the walls and ceilings of the barkcovered shelters formerly built by the lngura to protect themselves from the torrential downpours of the annual wet season. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

See Separate Article: AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL PAINTINGS ioa.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Australian Museum, National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2025