Home | Category: Aboriginals / Arts, Culture, Media

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIAN ART

"The Sea and the Sky," 1948 bark painting by Yolngu artist Munggerawuy Yunupingu (1905-1979), at the Art Gallery of South Australia; It relates to the start of the annual wet season in northeast Arnhem Land, when Macassans used to visit the northern shores of Australia to fish for trepang and other sea products; According to the gallery notes, "the upper section depicts the monsoonal thunderstorms", while "the depicted stingrays, which breed each wet season, represent the artist's totemic ancestors and the surrounding linear patterns evoke the movement of the seas"

Australian Aboriginal art is the world’s longest uninterrupted art tradition. It embraces works in a variety of mediums, such as painting on leaves, bark painting, wood carving, rock carving, watercolor painting, sculpture, ceremonial dress, sand painting, and crafts and objects such as shields, masks, boomerangs, bags and baskets. Indigenous Australians have been making art for tens of thousands of years and continue to make it today. There are a number of styles and processes, including rock painting, dot painting, rock engravings, bark painting, carvings, sculptures, weaving, and string art.

Aboriginal Australia art is inextricably interrelated with Aboriginal religion, culture, community, everyday life, laws and concepts of being and time. One member of the the Muthimuthi group told Rick Gore of National Geographic, "All Aboriginals are born artists. You would be too, but your culture has driven it out of you.” Aboriginal art comes in a number of different forms: dot paintings and batik printing from the central Australian desert; bark paintings from Arnhem Land; wood carvings and silk screens from the Tiwi Islands. In the past, Australia's Aboriginal peoples had almost no permanent architecture. They primarily painted representations of their diverse ancestral beings directly on the landscape, as rock art, and also created more ephemeral types of images during ceremonies.

Geraldine Brooks wrote in The New Yorker: Native Australians began painting rock walls fifty thousand years ago; early Europeans would not decorate the caves of Lascaux for another thirty-five thousand years. Traditional Aboriginal art was immensely varied. In the far north, groups made elaborate “X-ray” paintings of animal skeletons on bark and rock. In the northwest, they adorned cave walls with images of Wanjina, spiritual beings with huge eyes and no mouths. (These powerful creatures, it was believed, observed all things but passed no judgments.) When a white explorer, George Grey, first saw depictions of Wanjina, in 1837, he pronounced them “far superior to what a savage race might be supposed capable of,” and speculated that they might have been painted by wandering medieval knights. Few whites ever saw the more ephemeral art forms of desert Aborigines, such as ground paintings, which were communal works fashioned directly on the sand. [Source: Geraldine Brooks, The New Yorker, July 20, 2003]

In recent decades, Aboriginal art has become quite popular among art lovers, collectors and tourists. It has also found its way into white society and culture. Aboriginal art has decorated, Quantas planes, T-shirts and a wide variety of souvenirs and everyday items. There is a debate in the Aboriginal community as to whether this helps spreads Aboriginal culture in a positive way or demeans sacred images by commercializing them.

Book: “Dreamings: The Art of Aboriginal Australia”, edited by Peter Sutton (Asia Society Galleries/ George Braziller, 1989); “Journey in Time: The World's Longest Continuing Art Tradition: The 50,000 Year Story of the Australian Aboriginal Rock Art of Arnhem Land” by George Chaloupka (Chatswood, N.S.W.: Reed, 1993; “Australian Rock Art: A New Synthesis” by Robert Layton (Cambridge University Press, 1992)

RELATED ARTICLES:

VERY, VERY OLD AUSTRALIAN AND ABORIGINAL ROCK ART ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL PAINTINGS ioa.factsanddetails.com

MODERN AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL ART: PAPUNYA, MANGKAJA, REDISCOVERY, REVIVAL, AND A NEW AUDIENCE ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL ART FROM DIFFERENT REGIONS ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL ART OF NORTHERN AUSTRALIA: ANCIENT ROCK ART AND BARK PAINTINGS ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL ART FROM QUEENSLAND AND THE TORRES STRAIT ioa.factsanddetails.com

WELL-KNOWN ABORIGINAL ARTISTS: THEIR LIVES, WORKS AND IMPACTS ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS (FIRST NATION PEOPLE) OF AUSTRALIA: NAMES, DEMOGRAPHICS, LANGUAGES ioa.factsanddetails.com

EARLY MODERN HUMANS IN AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

LIFE OF EARLIEST HUMANS IN AUSTRALIA: TOOLS, WEAPONS, ART, SETTLEMENTS ioa.factsanddetails.com

PEOPLE WHO LIVED AUSTRALIA 20,000 TO 10,000 YEARS AGO ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

RITUAL LIFE AND MYTHS OF ANCIENT AUSTRALIANS ioa.factsanddetails.com

EARLY ABORIGINALS ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINALS AT THE TIME EUROPEAN COLONIZATION BEGAN ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIA ABORIGINALS FROM 1900 TO PRESENT: DISCRIMINATION, ASSIMILATION, SOME RESTITUTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIA’S STOLEN GENERATIONS: VICTIMS, LAWS, RATIONALE, OUTRAGE ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL RELIGION: TRADITIONAL BELIEFS, DEMOGRAPHY AND DEATH ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL CUSTOMS, SOCIETY AND RITUALS ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL LIFE: WHERE THEY LIVE, WORK, DIET, HEALTH, ALCOHOL ioa.factsanddetails.com

TRADITIONAL ABORIGINAL LIFE: FOOD, HOMES, HUNTING ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL MEN AND WOMEN: GENDER, MARRIAGE, SEX ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIAN SEX: PRACTICES, ATTITUDES, ADOLESCENCE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS IN QUEENSLAND: SOME GROUPS, CUSTOMS, LIFESTYLES ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIANS IN NORTH NORTHERN TERRITORY: SOME GROUPS, CUSTOMS, LIFESTYLE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS OF CENTRAL AUSTRALIA: SOME GROUPS, CUSTOMS, ART, LIFESTYLE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS IN WESTERN AUSTRALIA: SOME GROUPS, HISTORY, CUSTOMS, TRADITIONAL LIFE ioa.factsanddetails.com

History of Aboriginal Australian Art

The earliest art in Oceania was created by Australian Aborigines and consists of rock art and petroglyphs that depict myths about religion and nature. They also painted highly decorated geometric patterns on panels and boomerangs, a style still carried on by indigenous cultures today.[Source: barnebys.com]

Eric Kjellgren wrote: Australian Aboriginal art arose in a landscape fundamentally different from that of other regions. On this immense continent, crisscrossed by a network of trade routes, it is great expanses of land, rather than sea, that both separate and link Australia's Aboriginal peoples. When the first British settlers landed in Australia in 1788, its Aboriginal peoples spoke more than two hundred separate languages. Descendants of nearly all these different peoples survive today, but fewer than one hundred Aboriginal languages are still spoken. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

The ancestors of present-day Aboriginals first arrived on Australia's shores some forty thousand to sixty thousand years ago and went on to colonize even the most remote reaches of the continent. Although largely arid, Australia supports a diversity of environments, including savanna-like grasslands, temperate woodlands, and tropical rain forests. The Aboriginal peoples of all these areas developed distinctive artistic traditions.

Much of Australia's greatest art was, and is, executed on the landscape. The earliest Aboriginal peoples possessed, or rapidly developed, diverse and highly sophisticated traditions of rock art-paintings and engravings made on the walls of rock-shelters (shallow cavelike overhangs of rock) and other large outcrops of stone. By far the most ancient of all Oceanic art traditions, Aboriginal rock art has been produced for tens of thousands of years.

The earliest Aboriginal rock paintings may have been created some fifty thousand years ago, predating the Paleolithic-era painted caves of Europe by many millennia. Still practiced in some areas today, Aboriginal rock art is arguably the longest continuous artistic tradition in the world. In historical times, rock art was created for a variety of purposes. Some images were sacred: they were produced, or renewed, at supernaturally powerful sites within the landscape in order to honor ancestral beings or increase the abundance of game; some types were also made in conjunction with potent forms of malevolent magic.

Other images, such as those that adorned the walls of the rock-shelters in which the community camped, were secular; these were painted to commemorate a successful hunt or to instruct young children about aspects of the surrounding environment and sometimes simply for pleasure.3 In addition to painting on rock, artists in the Arnhem Land region formerly created identical paintings on the interior walls and ceilings of the bark-covered shelters that they constructed to prated themselves from the torrential rains of the annual wet season. The painted panels from such shelters were first seen and collected by Westerners in the nineteenth century. In the early decades of the twentieth century, outsiders increasingly began to encourage artists to create independent bark paintings for the art market, a practice that gave rise to Arnhem Land 's thriving contemporary traditions of Aboriginal bark painting.

Early Aboriginal Art

Up until fairly recently Aboriginal art was found only on rock paintings, ground paintings, toas (sculptured sticks) and body painting. Much of it was temporary. For obvious few examples of ancient body painting remain. Ground paintings were often destroyed after ritual rituals use. Toas often rotted away within a few months. Even though the art works didn't last the images did in the oral traditions passed on from one generation to the next.

The earliest examples of Aboriginal art are rock engraving of geometric shapes, bird and animal tracks, maze-like linear designs. Later came engravings of humans and animals followed stencil of hands and weapons, the simple one-color drawing and finally large multi-colored figures made with red and yellow ochers and white or cream pipe clay. Aboriginal art produced after the arrival of whites is often brutal and tragic.

Archaeologists have found centuries-old carvings on 12 boab trees in northern Australia. The exact age of the carvings is not yet known, but an archaeological team working with First Nations Australians believe the imagery is connected to Indigenous oral traditions. [Source: Isaac Schultz, GizmodoDecember 21, 2022]

Images and Meaning of Australia Aboriginal Art

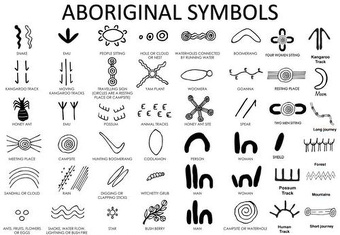

Aboriginal art images include ancestral beings such as the Rainbow Serpent, the Lightning Men and the Mandjina. Symbols are usually associated with a particular totemic ancestor and the spirit that lived within it in Dreaming (Dreamtime). The Aboriginal art most popular with Westerners often features crosshatched or pointillist abstractions. Many Aboriginal paintings are stylized maps of geographical features associated with Dreaming dots and circles representing paths and campsites, where important rituals were held.

Geraldine Brooks wrote in The New Yorker: Traditionally, Aboriginal artworks “were made during secret rites that celebrated the “creation ancestors”—supernatural beings who were thought to have formed every detail of the landscape, from sandhill to riverbank. The entire Australian continent, Aborigines believe, was shaped by the prehistoric travels of the creation ancestors; details about these epic journeys were passed down in narratives known as Dreamings. Each Aborigine inherited responsibility for a particular Dreaming story and the parcel of land on which it took place. In the desert, a ground painting depicting a Dreaming myth traditionally employed dots of colored ocher or tufts of plant fibre, carefully placed by the individual who had inherited the right to tell it. Soon after a ground-painting ceremony ended, the image was obliterated. As a result, much Aboriginal imagery remained unknown to outsiders. [Source: Geraldine Brooks, The New Yorker, July 20, 2003]

Mark Hudson wrote in the Japan Times: “An Australian archaeologist once told me that he had listened to an Aboriginal man talk for three hours about the meaning of a bark painting he had made. What to the uninitiated may have appeared to be no more than an attractive but random series of dots and lines was, the awed archaeologist admitted, in fact part of a complex web of stories and ideas. [Source: Mark Hudson, Japan Times, August 17, 2003]

Australia Aboriginal Art, Religion, Dreaming and Ceremony

Art is sacred to Aboriginals. Many of the images in the paintings depict Dreaming figures, mythical heroes, totemic ancestors, spirits, hunts, sorcery and love magic. Eric Kjellgren wrote: Despite the vast distances that separate the Aboriginal peoples of Australia, almost all of Aboriginal art and religion is united by the concept of the Dreaming (often previously called the Dreamtime). In a narrow sense, the Dreaming refers to the primordial creation period during which ancestral beings emerged from the featureless earth and traveled across its surface, creating both the physical features of the landscape, such as mountains and waterholes, and also the humans, plants, and animals that inhabit it. At first, these Dreaming beings were all in human form, and some, the ancestors of human beings, remained so. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

Most, however, subsequently transformed into animals, plants, or other natural phenomena, the ancestors of those that continue to sustain Aboriginal peoples today. Although most of its events took place in the distant past, the Dreaming is an ongoing phenomenon, and the creative (or destructive) power of Dreaming beings still lies within the landscape, where it can be accessed through ritual activities performed at specific sites. The concept of the Dreaming occurs throughout the continent, but religious life among each Aboriginal group revolves around the specific Dreaming beings who created their homeland. The great majority of human, animal, and plant images and geometric motifs that appear in Aboriginal art depict the beings, events, and sacred sites of the Dreaming, although some images are secular in nature.

Aboriginal art forms were, and are, directly associated with ceremonial life. Among most Aboriginal peoples, religious life is divided by gender; men and women each have their own sacred art forms, ceremonies, and Dreaming sites. These ceremonies often involve elaborate forms of personal adornment and the creation or reuse of sacred images and objects, whose forms were first prescribed during the Dreaming. Many of these art forms are ephemeral, created only for the brief duration of the rites, after which they are ritually destroyed. Others, made from more durable materials, are carefully concealed after use. The forms, imagery, and nature of many of these ceremonial artworks remain secret and highly sensitive subjects, which may not be revealed, even today.

Adornment of Objects in Aboriginal Art

Eric Kjellgren wrote: Aboriginal artists in the past devoted much of their energy to the creation and adornment of functional items, such as shields, boomerangs, spear throwers, and carrying trays, that were formerly used as part of daily life. This emphasis on practical objects resulted in part from necessity. Whereas other regions of Oceania are characterized by agricultural societies, Australian Aboriginal peoples in the past were hunter gatherers. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

Possessing a profound and intimate knowledge of the landscape, each group lived and moved about within a well-defined homeland according to the local or seasonal abundance of the water, game, and wild plants on which they depended for food. This highly mobile way of life, which required each person to carry all or most of his or her possessions to each new camp, resulted in the development of a spare and highly efficient ensemble of implements that, though eminently practical, were often exquisitely decorated. The designs on these objects are typically geometric, although figurative images occur in some areas. Some of these patterns may have been purely decorative, but many likely had important Dreaming associations.

Blue Pigments in Australian Aboriginal Art

Eric A. Powell wrote in Archaeology Magazine: For generations, Aboriginal artists of Australia’s West Arnhem Land region have used naturally occurring red, yellow, and white pigments to create their distinctive rock art. The area has no natural source of blue pigment. Scholars had believed that it wasn’t until the late 1920s that artists there first began using laundry blue, a dye introduced by Europeans, to create rock art featuring vibrant blue hues. In powder form, laundry blue was used to brighten white textiles. [Source: Eric A. Powell, Archaeology Magazine, September/October 2022

Now Griffith University archaeologist Emily Miller and her team have determined that Aboriginal artists were using laundry blue in West Arnhem Land at least a generation earlier than previously thought. The team found that fiber baskets and bark belts with blue accents were collected at a mission that existed for just a few years around 1900 in what is now Arnhem Land’s Kakadu National Park. Aboriginal artists in the area evidently already had access to the exotic blue dye. Miller points out that blue has a strong association with the life force of the Rainbow Serpent, an important creator being in many Aboriginal belief systems. “By incorporating this new vivid pigment in objects and rock art,” she says, “the artists were tapping into this life force.”

Highest Prices Paid for Aboriginal Artworks

The Australian economy gains $100 million annually from the sale of Aboriginal art. The highest prices ever paid for an Australian Aboriginal artwork was US$2.1 million for different paintings: 1) in 2017 for Emily Kame Kngwarreye's painting, “Earth's Creation I” (1994) and 2) in 2007 for Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri's painting “Warlugulong” (1977). There is some ambiguity over the valuations of these art works due to exchange rate difference between the Australia and U.S. dollars and inflation over time. [Source: Urban Splatter December 1, 2021]

Kngwarreye's painting “Earth's Creation I” was sold on Cooee Art Marketplace and Fine Art Bourse's online auction to Tim Olsen, an art dealer in New York, for a newly opened gallery. The Commonwealth Bank purchased Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri's Warlugulong for AU$1,200 in 1977. The bank sold the painting in 1996 for AU$36,000. The National Gallery of Australia paid AU$ 2.4 million (US$2.1 million) for it in a Sotheby's auction in July 2007.

“Water Dreaming” by Johnny Warangkula Tjupurrula reportedly sold for US$150 in 1973. The painting was sold for US$486,500 in 2000, a 3,243 percent increase in just 27 years.

Tommy Lowry Tjapaltjarri's most celebrated work, “Two Men Dreaming at Kuluntjarranya”, 1984, (lot 51) has an estimated value of US$225,000–US$338,000. Collectors regard it as one of Aboriginal’s art most aesthetically pleasing and exceptional paintings, and it has been shown in two of the field's most prestigious exhibitions: Dreamings.

High prices have also invited fraud. Paintings purportedly made by an Aborigine man named Eddie Burrup were actually made by an elderly white woman from Perth named Elizabeth Durack. The artist Edie Blitner Watts told the BBC, "It's just a big scam, as far as I'm concerned, because theirs that much fraud, there; that much people sitting there in sheds making false artifacts. Thousands and thousands of pieces of artwork that probably an Aboriginal hand doesn't touch it." Police have conducted raids of art galleries bringing along Aboriginal artists who identify art work attributed to them but not really produced by them.

Aboriginal Artists Gain Royalties for Resold Art

In 2008, it was decided that Australian Aboriginal artists, whose paintings sell for huge sums of money but often struggle to make ends meet, would get a royalty charge imposed on their resold works. Reuters reported: In a pointer to the problem, a distinctive work by late indigenous artist Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri was last year sold to the National Gallery of Australia for A$2.4 million after being originally purchased by a dealer for just A$2,500. [Source: Reuters, October 3, 2008]

Many outback painters receive only meager payments for works later sold on by galleries or middlemen for thousands of dollars, often to collectors overseas or in Australia’s major cities, the center-left government said. “By enshrining in law the right of artists and their heirs to receive a benefit from the secondary sale of their work, we are building an environment where the talent and creativity of visual artists receives greater reward,” Arts Minister Peter Garrett said.

Garrett, a former rock star, said a mandatory 5 percent royalty would apply to artworks sold for $1,000 or more. The resale royalty would apply to works by living artists and for a period of 70 years after an artist’s death. Garrett said the resale royalty for a visual artists brought struggling painters and photographers into line with other creators, such as authors and music composers. “This is an incredibly significant outcome for visual artists in Australia who in future will benefit financially when their works are sold on the secondary art market,” he said.

"Water Dreaming at Kalipinypa", by Johnny Warangkula Tjupurrula, 1973, Synthetic polymer powder paint on composition board, 61 x 40 centimeters

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Culture Shock! Australia, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated October 2025