Home | Category: Aboriginals / Arts, Culture, Media

AUSTRALIA ABORIGINAL PAINTINGS

Aboriginal paintings are more than just paintings. Representations of the world's oldest continuous living culture, they are a form of visual storytelling and knowledge transmission that uses a system of symbols and patterns to convey deep cultural, spiritual, and environmental meanings, They have their own visual language, with common motifs like concentric circles, foot prints and wavy lines representing spiritual beliefs, ancestral journeys, and elements of the natural world, varying by region and context.

Painting forms include ancient rock art, bark paintings, and modern acrylics on canvas, all manifestations of a tradition passed down for millenniums that with survival knowledge, ceremonies, and creation stories. Among the most well known styles are dot-mosaics and ‘X-ray’ animals complete with their skeletal structure and internal organs visible. Paintings often depict Dreaming stories, which are ancestral creation stories and journeys of the land, passed down through generations.

Art reflects a profound spiritual and cultural connection to the land, with symbols representing ancestral knowledge, native animals, and the creation of landscapes. Artwork is deeply connected to the spiritual beliefs of the people and represents their understanding of the Dreaming, the ancestral beings, and the universe. Modern paintings are a contemporary expression of long-standing traditions that include oral storytelling, songs, and ceremonies. The ability of Indigenous people to adapt to change has been crucial to the survival of their culture, which is reflected in their diverse art forms.

Aboriginal painting serves as a vital medium for transmitting stories, cultural knowledge, and spiritual beliefs across generations. The artistic process has traditionally been guided by Elders, who preserve the cultural integrity of the art and ensure that sacred knowledge is transmitted appropriately. While traditional art often used earthy ochers, the contemporary movement saw artists embrace acrylics and new mediums on canvas, which helped amplify their voice and share their culture globally.

RELATED ARTICLES:

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIAN ART ioa.factsanddetails.com

VERY, VERY OLD AUSTRALIAN AND ABORIGINAL ROCK ART ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

MODERN AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL ART: PAPUNYA, MANGKAJA, REDISCOVERY, REVIVAL, AND A NEW AUDIENCE ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL ART FROM DIFFERENT REGIONS ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL ART OF NORTHERN AUSTRALIA: ANCIENT ROCK ART AND BARK PAINTINGS ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL ART FROM QUEENSLAND AND THE TORRES STRAIT ioa.factsanddetails.com

WELL-KNOWN ABORIGINAL ARTISTS: THEIR LIVES, WORKS AND IMPACTS ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS (FIRST NATION PEOPLE) OF AUSTRALIA: NAMES, DEMOGRAPHICS, LANGUAGES ioa.factsanddetails.com

EARLY MODERN HUMANS IN AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

LIFE OF EARLIEST HUMANS IN AUSTRALIA: TOOLS, WEAPONS, ART, SETTLEMENTS ioa.factsanddetails.com

PEOPLE WHO LIVED AUSTRALIA 20,000 TO 10,000 YEARS AGO ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

RITUAL LIFE AND MYTHS OF ANCIENT AUSTRALIANS ioa.factsanddetails.com

EARLY ABORIGINALS ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINALS AT THE TIME EUROPEAN COLONIZATION BEGAN ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIA ABORIGINALS FROM 1900 TO PRESENT: DISCRIMINATION, ASSIMILATION, SOME RESTITUTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIA’S STOLEN GENERATIONS: VICTIMS, LAWS, RATIONALE, OUTRAGE ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL RELIGION: TRADITIONAL BELIEFS, DEMOGRAPHY AND DEATH ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL CUSTOMS, SOCIETY AND RITUALS ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL LIFE: WHERE THEY LIVE, WORK, DIET, HEALTH, ALCOHOL ioa.factsanddetails.com

TRADITIONAL ABORIGINAL LIFE: FOOD, HOMES, HUNTING ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL MEN AND WOMEN: GENDER, MARRIAGE, SEX ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIAN SEX: PRACTICES, ATTITUDES, ADOLESCENCE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS IN QUEENSLAND: SOME GROUPS, CUSTOMS, LIFESTYLES ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIANS IN NORTH NORTHERN TERRITORY: SOME GROUPS, CUSTOMS, LIFESTYLE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS OF CENTRAL AUSTRALIA: SOME GROUPS, CUSTOMS, ART, LIFESTYLE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS IN WESTERN AUSTRALIA: SOME GROUPS, HISTORY, CUSTOMS, TRADITIONAL LIFE ioa.factsanddetails.com

Aboriginal Australian Rock Paintings

Aboriginal art represents the world's longest continuous living culture, with ancient rock art dating back at least 18,000 years. Paintings of specific gods are often put in Dream Places where it is believed those gods dwell. Many of the painting are not paintings at all, the Aboriginal believe, but are images that have been placed where they are by the gods. Some rock paintings are tapped with sticks so their spirits can be released into nearby billabongs. [Source: "The First Australians" by Stephen Breeden and Belinda Wright, National Geographic February 1988]

Arnhem Land in north Australia is famous for its rock paintings. The paintings contain hand prints, dots and circles and images of animals, people, ancestral beings and even ancient Indonesian fishermen and European ships.

Rock painting are often found in caves or rock shelters, where new paintings have been placed over old ones. Many sites are secret because so the paintings won't be damaged and the spirits that occupy them won't be disturbed and possibly unleash misfortune or disasters.

Rock art evolved over times. The earliest rock paintings are hand or grass prints. These were followed by the "naturalistic" style of animals and people with outlines filled with color. These were followed by "dynamic" painting in which motion was conveyed with dotted lines and other symbols and mythological beings with human and animals parts appeared. Later came simple human silhouettes and "yam figures" (with people and animals drawn like yams and yams drawn like people and animals).

X–Ray Style of Arnhem Land Rock Art

Jennifer Wagelie wrote for the Metropolitan Museum of Art: The "X-ray" tradition in Aboriginal art is thought to have developed around 2000 B.C. and continues to the present day. As its name implies, the X-ray style depicts animals or human figures in which the internal organs and bone structures are clearly visible. X-ray art includes sacred images of ancestral supernatural beings as well as secular works depicting fish and animals that were important food sources. In many instances, the paintings show fish and game species from the local area. Through the creation of X-ray art, Aboriginal painters express their ongoing relationships with the natural and supernatural worlds. [Source: Jennifer Wagelie, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2002]

To create an X-ray image, the artist begins by painting a silhouette of the figure, often in white, and then adding the internal details in red or yellow. For red, yellow, and white paints, the artist uses natural ocher pigments mined from mineral deposits, while black is derived from charcoal. Early X-ray images depict the backbone, ribs, and internal organs of humans and animals. Later examples also include features such as muscle masses, body fat, optic nerves, and breast milk in women. Some works created after European contact even show rifles with bullets visible inside them.

X-ray paintings occur primarily in the shallow caves and rock shelters in the western part of Arnhem Land in northern Australia. One of the best known galleries of X-ray painting is at Ubirr, which served as a camping place during the annual wet season. Similar X-ray paintings are found throughout the region, including the site of Injaluk near the community of Gunbalanya (also called Oenpelli), whose contemporary Aboriginal artists continue to create works in the X-ray tradition.

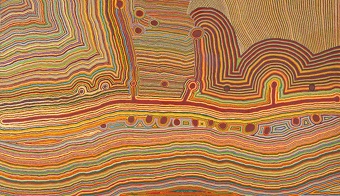

Dot-Paintings From Central Australia

Aboriginal dot-painting is perhaps the most well-known Aboriginal art form. Originating in central Australia, it is believed to have developed out of "ground paintings," paintings made on the ground during traditional ceremonies from pulped plant material in different colors dropped on the ground to make outline objects on rock painting and highlight geographical features.

Many of the dot paintings look abstract but to experienced observers they contain images that can be easily identified: the tracks of animals, people or birds; boomerangs; spears; digging sticks and coolamans (wooden carrying dish). The boomerangs and spears are often symbols of men and the digging sticks and coolamans are often symbols of women because these were tools associated with each sex. The dot paintings are often representations of Dream Place landscapes with concentric circles representing the Dream Places. Although the symbols can often be identified their context and association with other symbols is often known only to the artist.

Aboriginal dot painting is performed by applying paint in a series of dots using tools like sticks, skewers, or brush handles. Artists use a range of dot sizes to create intricate patterns and designs on canvas, wood, or other surfaces, with the technique originally developed to obscure secret iconography and depict stories, land, and cultural knowledge. The process can involve sketching outlines, layering dots of different colors to build up designs and create visual effects, and can range from traditional earth-toned ochers to vibrant acrylic paints.

Aboriginal dot painting are commonly made on canvas, wood, bark and cardstock. Historically, natural pigments like ocher and charcoal were used, but modern acrylic paints are now widely employed. Different tools create different dot effects: 1) Sticks and skewers are good for different-sized dots; 2) Brush handles or cotton buds can make perfectly round dots. 3) Squeeze bottles with fine nozzles are ideal for continuous dot application. 4) Fingers are used for specific effects or smudging.

Bark Painting from Northern Australia

Making a dot painting, from Kate Owen Studio

Bark paintings are relatively new art forms. There is no evidence of bark paintings before the late 19th century (they may have existed before then but nothing remains because bark deteriorates easily). Tourism has created a large demand for bark paintings. In the old days wax, plant resins and yolks from the eggs of wild birds were used as bonding agents and brushes were made from feathers, hair and leaf fibers. These days synthetic agents or wood glues are mostly used and brushed are the same as those bought by artists at art supply stores.

The bark used in bark painting comes the stringybark tree, a kind of eucalyptus. The bark is removed from the tree during the wet season when it is moist. The rough outer later is taken off and the inner bark is dried over a fire and pressed under weighs. All this takes about two weeks. Most bark paintings have a stick across the top and bottom to keep the bark flat. Most of the pigments are white (kaolin), black (charcoal) and red and yellow (ochers) because they were the same pigments used in body and rock painting.

Eric Kjellgren wrote: The bark paintings of northern Australia are one of the continent's most distinguished art forms. Although bark paintings are created in other areas, the most prolific bark painters are the peoples of the vast region of Arnhem Land and the islands off its shores. Sharing techniques, pigments, and iconography with the region's ancient rock art traditions, Arnhem Land bark paintings are rendered in ocher and other natural pigments on canvases made from fibrous sheets of bark peeled from the trunks of "stringybark" trees.' The stark black background of the present painting is characteristic of mid-twentieth-century works by the lngura people of Groote Eylandt, a large island that lies off Arnhem Land 's northeastern coast. As elsewhere in Arnhem Land, the contemporary barkpainting tradition on Groote Eylandt likely had its origin in the paintings made on the walls and ceilings of the barkcovered shelters formerly built by the lngura to protect themselves from the torrential downpours of the annual wet season. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

In contrast to sacred forms of painting, practiced in connection with ritual activities, the images painted in the bark shelters were spontaneous and secular, often made simply for pleasure or to help pass the long periods of enforced inactivity as the rains drenched the land outside. In some cases artists reportedly worked while lying on their backs, reaching up to adorn the underside of the low ceilings. Besides their recreational function, the paintings in the shelters were used to teach children about the appearance and characteristics of the animals, objects, totemic designs, and other subjects they portrayed. As the existence of Aboriginal bark painting gradually became known to the wider world during the first half of the twentieth century, artists throughout Arnhem Land began to create independent works on single sheets of flattened bark, which were destined for the fine-art market. On Groote Eylandt the first independent bark paintings were produced in the 1920s and 1930s, and the tradition continues to the present day. The earliest examples had backgrounds of var ing colors, but by the 1940s and 1950s virtually all lngura bark paintings were executed, as here, on solid black backgrounds. However, by the early 1960s lngura artists, likely inspired by the works of painters from neighboring areas of eastern Arnhem Land, began to fi ll the backgrounds of their works with complex geometric designs.

Bark Painting Images

Common images include Djangkawu, an ancestral spirit who traveled within elaborate dilly bag and digging stick used to create water holes; the Wagilag Sisters, linked with water holes and snakes; the Rainbow serpent Yingarna and her offspring Ngalyod; and the mimi spirits, who are credited with teaching the Aboriginals things like hunting, food gathering and painting.

Many bark paintings have distinctive cross hatch designs, are associated with particular clans and based on body painting designs. In addition, paintings from the ast have more geometric designs and those from the west have more naturalistic images and plane backgrounds.

Eric Kjellgren wrote: Like their artistic precursors on the interiors of the bark shelters, lngura bark paintings encompass a diversity of subjects. Many portray humans, animals, or plants. In some instances these are intended as images of ordinary people or food items, but in others they represent ancestra l bei ngs from the Dreaming (the primordial creation period) whose powers still endure within the landscape.8 Other works include representations of objects, constellations of stars, totemic designs, and the distinctive sailing vessels of the Makassans traders from eastern Indonesia who for centuries arrived annually to collect trepang (sea cucumber), highly valued as a delicacy in China. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

Compositions range from single figures to complex scenes from daily life or depictions of encounters with the Macassans and other historical events. The subject of one work by the Groote Eylandt lngura people, from 1940s-50s and measuring 30.5 x 50.8 centimeters (12 x 20 inches) is a bust of a fantastic creature with the crested head of a bird and the neck and shoulders of a human, it probably represents a being from the Dreaming, when the ancestors of present-day birds and animals walked the earth in human, or humanlike, forms.

Bark Painting from Groote Eylandt

One bark painting in the Metropolitan Museum of Art collection dates to the 1940s–1950s and was made by the Ingura people in Groote Eylandt. Made from bark and paint, it measures 30.5 x 50.8 x 0.6 centimeters (12 inches high, with a width of 20 inches and a depth of 0.25 inches). According to the museum: Groote Eylandt, in Anindilyakwa Country off the coast of northeast Arnhem Land, has been a center of bark painting since the 1920s. The heavy black background and dashed lines of red, white and yellow ochers that comprise this painting are characteristic of Anindilyakwa bark paintings from the middle of the twentieth century. The black pigment comes from the manganese that has been mined on Groote Eylandt for decades. Following the Second World War, some artists began extracting black pigment from the carbon in batteries that had been left on the island by Australian and American soldiers. [Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art]

The design of this painting is enigmatic. A label attached to the back of the bark titles the piece, Chasm Island and Big Shell. The image also resembles the head and shoulders of an anthropomorphic bird-like figure. Chasm Island, off the northern coast of Groote Eylandt is known as the site of the first European documentation of Aboriginal rock art, one of the oldest continuously practiced artistic traditions in the world. It is likely that this painting refers to the mapping of this Country, or to ancestral stories relating to this area that link the landscape to early narratives of creation and the formation of geographical features.The painting was originally sold through the Church Missionary Society.

The Groote Eylandt Mission was established at Emerald River in 1921. Its history is closely tied to the growth of the contemporary bark painting movement on the island. The first missionaries encouraged artists to produce portable barks that could be sold to provide income for the Mission. Artists began transferring the painted designs that previously decorated human bodies, rock shelters and the inner walls of bark huts onto bark panels. Designs associated with secret or sacred knowledge remained restricted to certain artists and ceremonies. By the middle of the twentieth century, when the current work was produced, Anindilyakwa paintings were becoming internationally recognized and represented in galleries and private collections.

Ngurrara Paintings

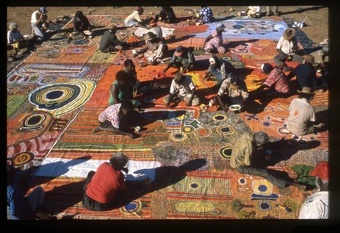

The two “Ngurrara” canvases produced in Western Australia have been described as “among the greatest works of indigenous art ever created”. They are among the largest and most spectacular Aboriginal Western Desert paintings and they have a powerful political significance to people of the Great Sandy Desert. Geraldine Brooks wrote in The New Yorker: “Ngurrara I,” the first attempt, was a canvas that measured sixteen feet by twenty-six feet and was worked on by nineteen artists. It was completed in 1996. But some elders and artists didn’t feel that it properly reflected all the important places and stories, so more than forty additional artists were enlisted to produce a more definitive version, “Ngurrara II” — which was twenty-six feet by thirty-two feet. [Source: Geraldine Brooks, The New Yorker, July 20, 2003]

Aboriginal lawyer and writer Larissa Behrendt wrote in the Aboriginal Art Directory: The artists met at Pirnini, an area to the south west of Fitzroy Crossing to create Ngurrara II. It was the second attempt to make such a canvas. In 1996 a canvas was produced but the artists were unhappy with it. Artists had worked independently on different parts of the painting, with different notions of scale and so the panels did not fit together the way that they should have. Learning from this experience, a larger canvas was used and there was also a better understanding of how the different elements of the painting should work together. The result is breathtaking in its scope. It captured the extremely strong affiliation to land that people had to the land they had lived off the land until the 1960s.

Its colossal size (measuring eight by ten meters) is the first thing one notices. The eye sweeps across the vast canvas like a wind across a landscape, drawn by the thick horizontal lines. It is then that our focus can rest on the ten careful, colourful harmonised patchworks, each denoting a different story, a different place, a different piece of evidence of connection and attachment to land. With a bird’s eye view, the canvas makes the viewer feel as though they are floating across the country. The waterholes, trees, salt lakes and people are visible. It shows the path of serpents and ancestors. It tells a panoramic story of ceremonies being performed, creation stories, of spirits, of snoring fathers. It makes sense that Ngurrara means home, the place that people have attachment to. And it literally became evidence.

Attachment of Aboriginals to the Ngurrara Paintings

Brooks wrote: In 2003, The artists decided to take a fresh look at “Ngurrara I,” which many of them hadn’t seen in years. It took three people to carry the canvas, and several more to unroll it over the dingy carpet that covered the workshop’s earth floor. Suddenly, the shed was filled with the colors and forms of the desert: swirls, dots, concentric circles, serpentine curls. A strong, dark line with circular protrusions bisects the canvas: it represents the Canning Stock Route, a series of wells sunk by white settlers in the early nineteen-hundreds for the convenience of inland cattle drovers. At the base of the painting—to the southwest, if you view the canvas as a map—Hitler Pamba’s salt-pan country spreads out in his characteristic opalescent wash. The gestural swirls of his wife, Stumpy Brown, depict the water holes that abut the livestock path to the east. Just above, Skipper’s signature quatrefoil, its acid green the brightest hue in the composition, draws the eye upward, cushioned by Chuguna’s more muted, less structured ovals. The sinuous curve of a snake spirit defines the top of the canvas. [Source: Geraldine Brooks, The New Yorker, July 20, 2003]

The elderly artists began slowly walking across the canvas, pointing, their voices rising with excitement. To anyone versed in the “Don’t touch” conventions of Western art, the sight of people walking on a masterpiece—in mud-crusted stock boots—was startling. It was also a reminder of how non-Western and unmaterialistic Aboriginal society remains....Two weeks later, “Ngurrara I” arrived in Melbourne, where Sotheby’s restorers cleaned every inch of the canvas with water and ethyl alcohol. “They said they couldn’t believe what came off it,” Klingender told me. “Buckets of red mud.” The canvas was gently ironed flat and then placed on an elaborately engineered stretcher; a new black border was added to mask the work’s irregular edges.

In Fitzroy Crossing, “Ngurrara II” awaited a different fate. As “Ngurrara I” was readied for display before the art world’s élite, the big canvas went on display in the bush. The Aborigines—the old artists and their young descendants—decided to take the painting on a journey to the place that it depicted. This past April, about thirty Aborigines set off from Fitzroy Crossing in a convoy of battered trucks and four-wheel drives. They made camp in a sandy bend of river on Cherrabun Station, the vast cattle ranch where Skipper and Chuguna had first encountered white people, almost half a century ago. In the bright sunlight of a clear morning, the canvas was unfurled on the ground. Among the artists who had come on the journey was Spider Snell, who, at just under eighty years old, is an elegant and surprisingly vigorous dancer. Snell is the custodian of an important ritual dance, the Kurtal ceremony, which is performed while carrying long, thread-wrapped boughs that represent the rain clouds controlled by the snake spirits. Accompanying him were three young apprentice dancers, boys who usually attend boarding school south of Perth, thousands of miles away. For three days, the old man shared his stories with the young ones—stories of dreaming, of water, of survival, and of a past kept alive for them in the thick swirls of paint beneath their feet.

For information on the sale of this painting and the complete article from which the material here is derived see “Painted Desert” by Geraldine Brooks, The New Yorker, July 20, 2003; there is a paywall newyorker.com

Ngurrara Paintings and Aboriginal Land Claims

Ngurrara 1 was presented for the National Native Title Tribunal claim for the Southern Kimberly community in 1997 as evidence of ancestral, social, economic and personal connections to land. Geraldine Brooks wrote in The New Yorker: Frustrated by their inability to articulate their arguments in courtroom English, the people of Fitzroy Crossing decided to paint their “evidence.” They would set down, on canvas, a document that would show how each person related to a particular area of the Great Sandy Desert—and to the long stories that had been passed down for generations. In 1997, “Ngurrara II,” which was twenty-six feet by thirty-two feet, was rolled out before a plenary session of the Native Title Tribunal. It was, one tribunal member said, the most eloquent and overwhelming evidence that had ever been presented there. The Aborigines could proceed to court. [Source: Geraldine Brooks, The New Yorker, July 20, 2003]

The idea of painting the canvas was that of Ngarralja Tommy May’s: “… we were wondering how to tell the court about our country. I said then if kartiya [Europeans] can’t believe our word, they can look at our painting. It all says the same thing. We got the idea of using our paintings in court as evidence.”

Aboriginal lawyer and writer Larissa Behrendt wrote in the Aboriginal Art Directory: The evolution of Aboriginal art, its incorporation of European mediums and navigation of European economies and demands, shows the triteness of making a distinction between “traditional” and “contemporary” Aboriginal art. The Ngurrara canvas provokes reflection on this false dichotomy. It is the largest work of art from the Great Sandy Desert and falls over two stories and can be viewed from various vantage points.

Jilpia Nappaljari Jones is one of the native title holders and is related to Kurntika Jimmy Pike. She says: “Fred Chaney from the Native Title Tribunal came over ten years ago. I explained to him that these were desert people. Some couldn’t read or write. We’ll paint our country.” The dominant legal culture has an emphasis on the written word, on economic rights and is focused on the individual. By stark contrast, Aboriginal law has an emphasis on oral transmission, the preservation and maintenance of culture and is communally owned. The Ngurrara canvas, by bringing an embodiment of Aboriginal law into the court for consideration by the dominant culture, communicated across the divide. The Ngurrara determination was the largest claim in the Kimberley region and recognized exclusive possession native title over about 76,000 square kilometers of land.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Culture Shock! Australia, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated October 2025