IMPORTANT HUMAN SITES IN AUSTRALIA FROM 20,000 TO 10,000 YEARS AGO

Some archaeological sites that existed 12,000 years ago: 1) New Guinea II Rockshelter; 2) Kenniff Cave; 3) Native Wells rockshelters; 4) Dabangay shell mounds; 5) Carpenters Gap 1 Rockshelter; 6) Puntutjarpa Rockshelter; 7) Malangangerr Rockshelter; 8) Arkaroo Rock; 9) Serpents’ Glen Rockshelter; 10) Glen Thirsty Well; 11) Puritjarra Rockshelter; 12) Bush Turkey 3 Rockshelter; 13) Devon Downs Rockshelter; 14) Roonka Flat Dune open site; 15) Koongine Cave; 16) Allen’s Cave; 17) Madura Cave; 18) Norina Cave; 19) Marillana A Rockshelter; 20) Loggers Shelter; 21) RTA G1; 22) Sassafras 1 Rockshelter; 23) Yengo 1 Rockshelter; 24) Warragarra Rockshelter; 25) Nimji Rockshelter; 26) Skew Valley midden; 27) Hooka Point midden; 28) Canunda Rocks midden; 29) Clybucca midden; 30) Muyu-ajirrapa midden; 31) Jordan River midden from Researchgate

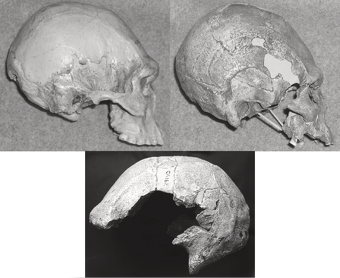

A cranium discovered in 1884 on the Darling Downs, Queensland was the first Pleistocene human skull found in Australia. It is dated to between 9000 and 11,000 years old. According to the Australia Museum: When it was found, the skull was covered in calcium carbonate, which gave the skull a deformed appearance. After cleaning, it was discovered that this skull belonged to a boy of about 15 years of age, who had died as a result of a blow to the side of the head. Features of the skull, such as the teeth and jaws, are remarkably large, but do fit within the range of variation of the Australian Aboriginal population. [Source: Fran Dorey, Australia Museum, September 12, 2021]

The Coobool Creek collection consists of the remains of 126 individuals excavated from a sand ridge at Coobool Crossing, New South Wales, in 1950. After their excavation, they became part of the University of Melbourne collection until they were returned to the Aboriginal community for reburial in 1985. The remains date from 9000 to 13,000 years old and are significant because of their large size when compared with Aboriginal people who appeared within the last 6000 years. They are physically similar to Kow Swamp people with whom they shared the cultural practice of artificial cranial deformation.

One of many cultural practices that can alter the appearance of human skeletons is skull deformation. There is evidence that some Aboriginal groups did practise skull deformation in ancient times. Australian scientist Dr Peter Brown proposed that the ‘robust’ features seen in skulls such as ‘Cohuna’ and those from Kow Swamp and Coobool Creek are the result of such practices in the past. Prolonged pressing and binding of the head can produce characteristics such as long receding foreheads, flat frontal and occipital bones and lengthening of the skull.

Carpenters Gap 1 rockshelter is one of the oldest radiocarbon dated sites in Australia and one of the few sites in the Sahul region to preserve both plant and animal remains down to the lowest Pleistocene aged deposits. Occupation at the site began between 51,000 and 45,000 years ago and continued into the Last Glacial Maximum, and throughout the Holocene. Archaeology work depict a remarkable record of adaptation in technology, mobility, and diet breadth spanning 47,000 years.

Puritjarra has some of the oldest rock art in Australia and a stone artifact typology stretching over 30,000 years . Many archeological excavations have taken place here. Dateed to at least 32,000 years ago, the rock shelter has a sandy floor and a reliable water source nearby. At the site, there are some rock art engravings in stone. Flaked stone artifacts include some made from locally sourced materially (silicified sandstone, clear quartz and ironstone) and some from other materials sourced from further away (white chalcedony, nodular chert, and silcrete).

Related Articles:

DID HUMANS REALLY MIGRATE TO AUSTRALIA 65,000 YEARS AGO ioa.factsanddetails.com

HOW THE FIRST PEOPLE GOT TO AUSTRALIA 50,000 (MAYBE 65,000) YEARS AGO ioa.factsanddetails.com

EARLY MODERN HUMANS IN AUSTRALIA factsanddetails.com ;

OUT OF AFRICA AND THEORIES ABOUT EARLY MODERN HUMAN MIGRATIONS factsanddetails.com ;

MIGRATIONS OF EARLY MODERN HUMANS factsanddetails.com ;

EARLY MODERN HUMANS MIGRATE TO ASIA factsanddetails.com ;

LIFE OF EARLIEST HUMANS IN AUSTRALIA: TOOLS, WEAPONS, ART, SETTLEMENTS ioa.factsanddetails.com

EARLY ABORIGINALS ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

VERY, VERY OLD AUSTRALIAN AND ABORIGINAL ROCK ART ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT ABORIGINAL ART OF NORTHERN AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

RITUAL LIFE AND MYTHS OF ANCIENT AUSTRALIANS ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN HISTORY ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

MODERN HUMANS 400,000-20,000 YEARS AGO factsanddetails.com

Kow Swamp People

Kow Swamp is ancient burial site in northern Victoria excavated between 1968 and 1972. According to the Australian Museum: The human skeletons discovered here were extremely significant because they were accurately dated between 9500 to 14,000 years ago and demonstrated substantial differences between ancient and more recent Aboriginal people.

The remains of over forty individuals have been found at Kow Swamp and include those of men, women and children. This burial site is one of the largest from this time period anywhere in the world. Many of the skeletons have a greater skeletal mass, more robust jaw structures and larger areas of muscle attachment than in contemporary Aboriginal men. The female skeletons from this region also show similar differences when compared with modern Aboriginal women.

‘Kow Swamp 1’ — a Human skull rediscovered in 1967 in the National Museum of Victoria by Alan Thorne and Phillip Macumber — is dated at 10,000 years old. The skull’s original burial location was traced through police reports, and excavations at Kow Swamp began soon after. 'Kow Swamp 5’ is 13,000-year-old skull and is one of the better-preserved examples from Kow Swamp. It has a greater skeletal mass, a more robust jaw structure and larger areas of muscle attachment than in contemporary Aboriginal men. ‘Kow Swamp 14’ refers to the remains were of a male skeleton whose knees were drawn up under the chest, with his hands in front of his face. In other Kow Swamp burials the skeleton was fully extended. It is not known why different burial positions were used.

A skull was found in 1925 at Cohuna, north-west Kow Swamp, Victoria, and is undated. However, the similarity between this skull and the Kow Swamp people suggests they are both from a similar time period. This skull’s long, high, flat forehead reflects the characteristics of cranial deformation and its teeth and palate are larger than the current Australian average.

20,000-Year-Old Human Footprints Found in Australia

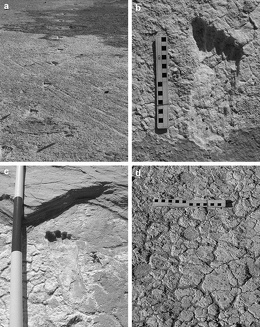

More than 450 footprints between 19,000 and 20,000 years have been discovered in southeastern Australia, the largest such group ever found. The were found along the Willandra Lake system — then an oasis with lots of fish and game — in Mungo National Park in New South Wales, about 315 kilometers (195 miles) from Broken Hill. A kangaroo hopped through the area and an emu chick showed up, suggesting it was spring. Scientists identified the paths of 22 individuals. Some are quite large and scientists estimate they may have made by people almost two meters tall. [Source: National Geographic]

Some of the footprints were made by people running. The runners were tall, well fed and athletic, Mud oozed between their toes as the ran. The prints were made in calcareous clay which hardened rapidly and became like concrete. Silty clay and sand covered them until they were exposed by wind erosion. Radar test reveal that the clay pan continues for several hundred more meters, under sand dunes, so perhaps thousands more footprints can found.

Sean Markey wrote in National Geographic: Woven among the sand dunes of the now arid Willandra Lakes World Heritage area are some 700 fossil footprints, 400 of them grouped in a set of 23 tracks. First spotted in 2003 by a young Mutthi Mutthi Aboriginal woman named Mary Pappen, Jr., the tracks are the oldest fossil human footprints ever found in Australia and the largest collection of such prints in the world. [Source: Sean Markey, National Geographic, August 4, 2006]

Steve Webb is a biological archaeologist with Bond University in Queensland. As of 2006, he and his colleagues had identified about 700 footprints. He says ground-penetrating radar suggests thousands more prints may lie below the ground in at least eight layers of ancient mud stacked like trodden carpets. Mary Pappen, Sr., a Mutthi Mutthi tribal elder and Pappen Jr.'s mother, says the age of the footprints highlights just how clever and adaptable Aboriginal ancestors were. "We did not die 60,000 years ago. We didn't dry up and die away 26,000 years ago when the lakes were last full," she said. "We are a people that nurtured and looked after our landscape and walked across it, and we are still here today."

Humans Who Made the 20,000-Year-Old Footprints in Australia

Sean Markey wrote in National Geographic: About 20,000 years ago, five human hunters sprinted across the soft clay on the edge of a wetland. Others also wandered across the muddy landscape, including a family of five, a small child, and a one-legged man who hopped without a crutch. Webb has studied and partially excavated the tracks with help from other scientists and members of three area Aboriginal tribes. In December 2005 he published a study in the online edition of the Journal of Human Evolution describing eight of the tracks. Webb says the footprints reveal things that archaeological sites or skeletal remains couldn't. For example, "these people were very active in this area, and we wouldn't have guessed that," he said. [Source: Sean Markey, National Geographic, August 4, 2006]

The footprints also held puzzles, such as the tracks of what experts say was a one-legged man. "All we could pick up was the right foot," Webb said, adding that each step left a very deep impression in the mud. "It's a very good impression," he said. "It's one of the best foot impressions there is on the whole site. But there is no sign of the left foot at all." The conundrum was solved with the help of five trackers from the Pintubi people of central Australia.

"They looked at the … track and said, Yes, it's definitely a one-legged man," Webb said. "Now, these people are able to tell you whether a woman's got a baby on her hip when she's walking along and whether she moves that baby from the right hip to the left hip." "So they see nuances of tracks in a way we have no skill in doing whatsoever." It helped that the Pintubi knew a living one-legged man from their own community. "They knew what a one-legged man could do," Webb said. The trackers believe the ancient man probably threw his support stick away and hopped quite fast on one foot. The trackers "gave us an amazing insight, just showing us small things which we hadn't even looked at," Webb said. One such detail was a set of small, round holes where a man stood with a spear. Another was a squiggle in the mud, perhaps drawn by a child.

Webb's own track analysis has yielded some intriguing conclusions, particularly for the prints left by a group he calls the Five Hunters. The archaeologist used data from 17,000-year-old human remains excavated nearby and details from the tracks themselves, such as foot size and stride length. The bones suggest the people were tall, in good health, and very athletic. What's more, Webb calculates that one hunter was running at 23 miles (37 kilometers) an hour, or as fast as an Olympic sprinter. "If you weren't fit in those days, you didn't survive," Webb said.

People Ate Kangaroo 20,000 Years Ago in Northwest Australia

In 2018, archaeologists announced they had uncovered a huge trove of ancient artefacts — including evidence of a kangaroo barbecue — inside a remote cave in the far north-west of Australia, 10 kilometers from BHP Billiton’s Mining Area C iron ore mine in the Hamersley Ranges of the West Australian Pilbara region. A team of scientists from Scarp Archaeology and BHP, led by Michael Slack, said: “The guys have just uncovered an ancient campfire that, given the depth below the surface and the relationship with the stones around it, we think is potentially around 20,000 years old,” Dr Slack said. [Source: Ancientfoods, June 20, 2018, Original Article: Karen Michelmore, abc.net.au]

ABC (Australian Broadcasting Corporation) reported: The remnants of the ancient camp fire consist of about 20cm of fine white ash and contains pieces of charcoal which will be sent off for radiocarbon dating. “To make it even better, they found flake stone artefacts right next to the charcoal,” he said. “So we’ll get a really good association between people and the campfire itself, and we’ll have a really clear idea of how old it is.”

It was possible the stone tools were used to cut the meat for the fire, as remnants of kangaroo bone were also found. “We’ll have to have a look at them under the microscope, but they are the pieces that people were using in the site,” Dr Slack said. “A family sitting around a campfire having a meal probably.”

Using garden trowels, the scientists are painstakingly digging centimetre by centimetre, through thousands of years of history. “You only have to look at the ground in this cave and you’ll see hundreds and hundreds of little chips of stone, and these were all coming off stone artefacts that were used as tools,” Dr Slack said. “Some of them just look really pretty, others you can see have lots of evidence of wear on the side.

“This little cave has hundreds of them on the surface which is very rare for the Pilbara. “Quite often the caves have nothing … but they are lying around. “We looked at a bunch of caves out here and as soon as we got to this one we thought, ‘wow we really want to come and do some archaeology here’ — it’s going to be really rich and there’s the potential there to tell a good story about what the Aboriginal people were doing here over possibly the last 40,000 years.”

The site was discovered in the late 2000s by a survey party made up of Aboriginal traditional owners working with BHP Billiton as part of their mine compliance requirements. Years later scientists returned to do a test dig in a 1m-square patch, and in the process uncovered a cache of stone tools, some of which are up to 32,000 years old, making it one of the oldest sites in the region. “The artefacts span what’s known as the last glacial maximum, or what most people know as the last ice age, between 18,000 years ago and 28,000 years ago,” Dr Slack said. Dr Slack, who is also president of the Australian Archaeological Association, said there are around 600 archaeologists working around Australia. But in terms of the size in Australia and the number of places that we know to be over 10,000 years, we are still only looking at dozens of places in the continent, in the period of up to 65,000-70,000 years [old].

Grains and Bread Eaten by Ancient Australians

In his 2014 book, “Dark Emu”, Bruce Pascoe detailed the advanced Aboriginal agricultural practices documented by early white settlers and effectively negating the theory that Indigenous Australians led a simple hunter-gatherer lifestyle. Indigenous Australians were among the world’s first agriculturalists, Pascoe told the BBC. [Source: Sarah Reid, BBC, March 2, 2021]

Sarah Reid of the BBC wrote: Native crops once thrived in Australia, particularly in arid regions, and were once skilfully managed by Indigenous Australians using techniques such as controlled burning (a practice now being harnessed to manage Australia’s notorious bushfires). But crops including grasses, the seeds of which were harvested to make flour, were decimated by the removal of Aboriginal people from their ancestral lands and the introduction of cattle. “The first explorers and pioneers that went into those regions wrote about grasses higher than their saddles, but they don’t exist in many of those places anymore,” said Pascoe.

While studying introduced crops for heat and drought tolerance at the University of Sydney’s agricultural research station on Gamilaraay Country in north-western New South Wales, agricultural scientist Angela Pattison began to wonder if hardy native grasses had the potential to become a sustainable food source in the face of Australia’s worsening droughts. “The native millet was the easiest to grow, harvest and turn into flour, and it’s significantly more nutritious than wheat,” said Pattison. “It’s also high in fibre and gluten free. And it tastes good. It just ticks so many boxes.”

It just ticks so many boxes. Researchers also found that native grasses have myriad environmental benefits. As perennials they sequester carbon, preserve threatened habitats and support biodiversity. This wasn’t exactly news, however, to the descendants of Australia’s first farmers — for whom the revival of native grains has more than just environmental and potential economic benefits.

Were Indigenous Australians the World’s First Bakers?

The 1990s discovery of a grinding stone in Cuddie Springs in north-west New South Wales dated to be at least 30,000 years old — followed by the 2015 discovery of a grinding stone in Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory found to have been used 65,000 years ago — has led Pacoe and other to believe that Indigenous Australians were the world’s first bakers. “The signs indicate that these grinding stones were used to make flour,” Pascoe, who has Aboriginal ancestry, told the BBC. “And that’s the first time in the world that grass seeds had been turned into flour by many thousands of years.” Even before the Arnhem Land discovery, said Pascoe, “The Cuddie Springs grinding stone showed that Ngemba women [the local Aboriginal clan] were making bread from seed 18,000 years before the Egyptians.” [Source: Sarah Reid, BBC, March 2, 2021]

The Indigenous word for bread varies between language groups (there were more than 250 Indigenous languages spoken in Australia at the time of colonisation). As part of a study, Pascoe joined Pattison and Gamilaraay Traditional Owners at a series of “johnny cake days” to test how various native flours held up in an Indigenous flatbread cooked over hot coals. Sarah Reid of the BBC wrote: It’s high in fibre and gluten free. And it tastes good. For Rhonda Ashby, a Gamilaraay woman who has been recognised for her work helping Aboriginal people re-engage with language and culture, it wasn’t just an opportunity to break bread with her kin, but also to heal. “We’ve lost a lot of knowledge though our colonisation,” said Ashby. “So, bringing back this traditional practice, being able to cook with our traditional ingredients, is really important for our wellbeing.”

Native grasses aren’t just a traditional food source for Gamilaraay people, she explained. They also have deep cultural significance, particularly for women. “The people of western New South Wales are known as the river and grass people, and these native grasses carry important Songlines [ancient wayfaring routes across the landscape, passed down over generations by story and song] like the Seven Sisters Songline, which is one of the biggest Songlines in Australia for First Nations women,” Ashby said.

First Americans from Australia?

Inhabitants of what is now Australia travelled by canoe to settle in the Americans more than 30,000 years ago, some anthropologists have argues. Reuters reported: in 2004 They would have island hopped via Japan and Polynesia to the Pacific coast of the Americas at a time when sea levels were lower than they are today, Dr Silvia Gonzalez from John Moores University in Liverpool said annual meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science in Exeter in 2004. The claim will be unwelcome to today's native Americans who came overland from Siberia and say they were there first. Most researchers say they came across the Bering Straits from Russia to Alaska at the end of the Ice Age, up to 15,000 years ago. [Source: Reuters, September 7, 2004]

But Gonzalez said skeletal evidence pointed strongly to Australian origins and hinted that recovered DNA would corroborate it. "This is very contentious," said Gonzalez. "[Native Americans] cannot claim to have been the first people there." She said there was very strong evidence that the first migration came from Australia to the Pacific coast of America. Skulls of a people with distinctively long and narrow heads discovered in Mexico and California predated by several thousand years the more rounded features of the skulls of native Americans.

One particularly well preserved skull of a long-face woman had been carbon dated to 12,700 years ago, whereas the oldest accurately dated native American skull was only about 9000 years old. She said there were tales from Spanish missionaries of an isolated coastal community of long-face people in Baja California, known as the Pericues, who were of a completely different race and rituals from other communities in America at the time. "They appear more similar to southern Asians and the populations of the Pacific Rim than they do to northern Asians," she said. "You cannot have two face shapes coming from the same place." The last survivors were wiped out by diseases imported by the Spanish conquerors, Gonzalez said.

First Americans had Indigenous Australian Genes

Indigenous South Americans share DNA with indigenous people in Oceania and Australia Laura Geggel of Live Science wrote: During the last ice age, when hunters and gatherers crossed the ancient Bering Land Bridge that connected Asia with North America, they carried something special with them in their genetic code: pieces of ancestral Australian DNA. Over the generations, these people and their descendants trekked southward, making their way to South America. Even now, more than 15,000 years after these people crossed the Bering Land Bridge, their descendants — who still carry ancestral Australian genetic signatures — can be found in parts of the South American Pacific coast and in the Amazon, researchers have found. "Much of this history has unfortunately been erased by the colonization process, but genetics is an ally to unravel unrecorded histories and populations," study senior researcher and professor Tábita Hünemeier and study co-lead researcher and doctoral student Marcos Araújo Castro e Silva, both of whom are in the Department of Genetics and Evolutionary Biology at the University of São Paulo in Brazil, told Live Science [Source: Laura Geggel, Live Science, April 2, 2021]

The new research builds on earlier work, first published in 2015, which showed that ancient and modern Indigenous people in the Amazon shared specific genetic signatures — known as the Ypikuéra, or Y signal — with modern-day Indigenous groups in South Asia, Australia and Melanesia, a group of islands in Oceania. This genetic connection caught many scientists off guard, and it remains "one of the most intriguing and poorly understood events in human history," the researchers wrote in the new study.

To investigate the Y signal further, a team of scientists in Brazil and Spain dove into a large dataset containing the genetic data of 383 Indigenous people from different parts of South America. The team applied statistical methods to test whether any of the Native American populations had "excess" genetic similarity with a group they called the Australasians, or Indigenous peoples from Australia, Melanesia, New Guinea and the Andaman Islands in the Indian Ocean. In other words, the team was assessing whether "a given Native American population shared significantly more genetic variants with Australasians than other Native Americans do," Hünemeier and Araújo Castro e Silva said. South American groups that did have more genetic similarities with Australasians were interpreted by the new researchers as being descendants of the first Americans and Australasian ancestors, who coupled together at least 15,000 years ago.

As expected, the study confirmed the previous findings of Australasian genetic ties with the Karitiana and Suruí, Indigenous peoples in the Amazon. But the new genetic analysis also revealed a big surprise: The Australasian connection was also found in Peru's Chotuna people, an Indigenous group with ancestral ties to the Pacific Coast; the Guaraní Kaiowá, a group in central west Brazil; and the Xavánte, a group on the central Brazilian Plateau. When the team looked specifically at the Chotuna people and other coastal Indigenous peoples, including the Sechura and Narihuala, the researchers found that these peoples had ancestry from a mix of South American people and a sister branch of the Onge, Indigenous people who live on Little Andaman island. When the team included the Xavánte people in the analysis, the model suggested that the coastal groups got started first, and later gave rise to the inland Amazonian groups with Australasian heritage.

How People with Indigenous Australian Genes Got to South America

Laura Geggel of Live Science wrote: The first settlers of America with Australasian genes “likely "stuck to the Pacific coast due to their subsistence strategies and other cultural aspects adapted to life by the sea," Hünemeier and Araújo Castro e Silva wrote in an email. "For this reason, they would have at least initially only expanded through and settled the whole American Pacific coast from Alaska until southern Chile. In this context, the expansion to the Amazon, passing through the northern Andes, would have been a secondary movement." [Source: Laura Geggel, Live Science, April 2, 2021]

According to archaeological records, a settlement on the Pacific coast dates to about 13,000 years ago, the researchers said. This jibes with the time frame the team suggested for the initial migration and the later inland coupling events in South America, which likely happened between 15,000 and 8,000 years ago, respectively, they said. Furthermore, while previous research suggested that there were two waves of first Americans who left Beringia about 15,000 years ago, and likely several waves from Beringia after that, the new study found that "one of the waves that came by the Pacific route was composed by individuals carrying some Australasian ancestry," Hünemeier and Araújo Castro e Silva said.

As to why the Y signal isn't found in North American Indigenous peoples, the "authors suggest that if such a migration had traveled rapidly along the Pacific coast of North America into Central and then South America, then it could explain why the signal is present predominantly in South America (both on the Pacific coast and in the Amazon), but not in North American Indigenous groups," Ioannidis said. Or, perhaps Indigenous people in North and Central America who had the Y signal were wiped out during Europe's colonization of the New World, Hünemeier and Araújo Castro e Silva said.

The researchers acknowledged that news of the Australasian-South American connection might spark ideas of an ancient sea voyage in the public's imagination. But the genetic model the team developed shows no evidence of an ancient boating expedition between South America and Australia and the surrounding islands at that time, the researchers said. Rather, the team emphasized, this ancestry came from people who crossed the Bering Land Bridge, probably from ancient coupling events between the ancestors of the first Americans and the ancestors of the Australasians "in Beringia, or even in Siberia as new evidence suggests," Hünemeier and Araújo Castro e Silva told Live Science. "What likely happened is that some individuals from the extreme southeastern region of Asia, that later originated the Oceanic populations, migrated to northeast Asia, and there had some contact with ancient Siberian and Beringians," Araújo Castro e Silva said. Put another way, the Australasians' ancestors coupled with the first Americans long before their descendants reached South America, the researchers said. "It is as if these genes had hitched a ride on the First American genomes," Hünemeier and Araújo Castro e Silva said. The study was be published in the April 6, 2021 issue of the journal the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Australian Museum, National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2025