Home | Category: Aboriginals

ABORIGINALS IN QUEENSLAND

There are almost 300,000 Aboriginal's in Queensland, the largest population of Aboriginals in any state in Australia. They and whites there have traditionally been at odds on many issues, mostly land. Some Aboriginals there are quite activist and the federal government has supports them not white Queenslanders on many issues

Aboriginals have lived in Queensland for 50,000 years. Some of their rock paintings are older than the famous paleolithic caves in Europe. At least some of the Aboriginals are believed to have arrived in Australia from New Guinea across a land bridge that once connected it to Australia's Cape York.

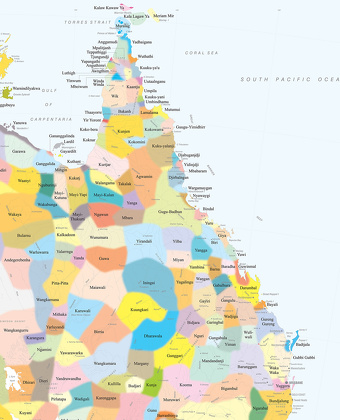

Queensland has many distinct Aboriginal language groups, such as the Djabugay, Yirrganydji, Yidinji, Wakka Wakka, Turrbal, Jagera, Kabi Kabi, Jinibara, and Warlpiri communities, each with specific cultural identities, languages, and connections to Country. These groups inhabit different regions across Queensland, from the Far North to the Darling Downs and south-east areas like Brisbane and the Moreton Bay region.

Djabugay, Yirrganydji, and Yidinji are some of the Traditional Custodians of the region around Cairns. The Jagera, Giabal, and Jarowair inhabited the Darling Downs region for thousands of years before European settlement. The Wakka Wakka are A group from the upper and central Burnett River region, encompassing areas like Gayndah, Murgon, and Nanango. Turrbal, Kabi Kabi, and Jinibara are the Traditional Custodians of the area covered by the City of Moreton Bay. Wik-Mungkan is one example of many group that live on the Cape York Peninsula in Far North Queensland.

RELATED ARTICLES:

ABORIGINALS (FIRST NATION PEOPLE) OF AUSTRALIA: NAMES, DEMOGRAPHICS, LANGUAGES ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIANS IN NORTH NORTHERN TERRITORY: SOME GROUPS, CUSTOMS, LIFESTYLE ioa.factsanddetails.com

YOLNGU OF ARNHEM LAND: HISTORY, MUSIC, TRADITIONAL LIFE, CUSTOMS ioa.factsanddetails.com

TIWI PEOPLE OF NORTHERN AUSTRALIA: HISTORY, CUSTOMS, TRADITIONAL LIFE ioa.factsanddetails.com

EARLY MODERN HUMANS IN AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

LIFE OF EARLIEST HUMANS IN AUSTRALIA: TOOLS, WEAPONS, ART, SETTLEMENTS ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINALS AT THE TIME EUROPEAN COLONIZATION BEGAN ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIA ABORIGINALS FROM 1900 TO PRESENT: DISCRIMINATION, ASSIMILATION, SOME RESTITUTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIA’S STOLEN GENERATIONS: VICTIMS, LAWS, RATIONALE, OUTRAGE ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL RELIGION: TRADITIONAL BELIEFS, DEMOGRAPHY AND DEATH ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL CUSTOMS, SOCIETY AND RITUALS ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL LIFE: WHERE THEY LIVE, WORK, DIET, HEALTH, ALCOHOL ioa.factsanddetails.com

TRADITIONAL ABORIGINAL LIFE: FOOD, HOMES, HUNTING ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL MEN AND WOMEN: GENDER, MARRIAGE, SEX ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIAN SEX: PRACTICES, ATTITUDES, ADOLESCENCE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIAN ART ioa.factsanddetails.com

Aboriginal Art from Queensland

North Queensland features extraordinary rock art. Many feature the Quinkan spirits, which come in two forms: the crocodile-like Imjim with knobbed club-like tails; and 2) the stick-like Timara. Clubs, shields, boomerangs and woven baskets have been made with a wide variety of designs.

There are also a number of Aboriginal art objects from Queensland in museums such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, including a mid to late 19th century spear thrower, made of wood, shell, resin and paint, from Aurukun on Cape York. It measures 89.2 x 8.9 x 2.2 centimeters (35.1 x 3.5 x D. 0.9 inches)

A shield, dating to the late 19th–early 20th century, form Central Queensland is made from wood, paint and is 9 3/4 inches high, with a width of 25 5/8 inches (24.8 x 65.1 centimeters). With its strongly convex surface, oval form, and brightly painted designs, this shield is likely from western Queensland. Carved from soft, light-weight wood, it served to ward off weapons, such as clubs, spears, or boomerangs, wielded or thrown by an opponent during fighting. Shields in western Queensland were decorated using a variety of techniques. Some examples were adorned with engraved designs, others were painted, and some were decorated using a combination of the two techniques. The present work is painted with a bold, hourglass-shaped motif in red, white, and black pigments. Although a number of motifs appear repeatedly on shields from this region, there is no historic information on the significance of the individual designs. [Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art]

The Metropolitan Museum of Art collection also contain a basket (Jawun) made by Northern Queensland people in the late 19th–early 20th century. According to the museum: The unique bicornual ("two-horned") baskets known as jawun produced by the rainforest peoples of northeastern Queensland in Australia are among the most elegant and versatile baskets in Oceania. Created only in the comparatively small region that lies between the modern settlements of Cooktown in the north and Cardwell in the south, jawun were used for collecting and processing food and, in the case of larger examples, at times for carrying young infants. The baskets had two handles, only vestiges of which remain on the present example. The first, a short loop, was used to hang the basket from a tree branch or the post of a shelter to keep the contents safe from animals. The second was a long, straplike handle that was looped around the wearer's forehead, allowing the basket to be worn hanging down the back to keep the user's hands free. Jawun were used for collecting and carrying food, such as nuts and seeds, on forays in the rainforest.

See Separate Article: AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL ART FROM QUEENSLAND AND THE TORRES STRAIT ioa.factsanddetails.com

Wakka Wakka

The Wakka Wakka are an Aboriginal people whose traditional lands are in the Burnett River region of central Queensland, including areas like Kingaroy, Murgon, Gayndah, and Eidsvold. Also known as the Wakkawakka, Wakawaka, Waka Waka and Wakka people, they were formally recognised as the native title holders of this land — covering over almost 1,180 square kilometers — in 2022 and are engaged in cultural heritage preservation, environmental management, and language revival efforts.

The total area of claimed by the Wakkawaka lands extends over some 11,000 square kilometers (4,100 square miles) running northwards from Nanango to the area of Mount Perry. Their western extension was at the Boyne River, the upper Burnett River, and Mundubbera. They were also present in the areas of Kingaroy, Murgon, and Gayndah.

The history of the Wakka Wakka people includes a dark past involving frontier violence, segregation, and forced removal, often described as similar to a concentration camp. On some of their sexual habits, John Stanislaw Kubary (1846-1896) wrote: “The mothers make the girls fit for copulation prematurely, by breaking the hymen with their fingers. This operation is secret, it is true, but takes place all the same. The mother moreover admonishes the girl to demand proper payment for her favours. The mother sees to it that at the copulation no inconvenience is experienced due to the early age of the girl, by regularly stretching the vulva by little rolls of leaves...The mother sends the child out on her first sexual adventures”. [Source: “Growing Up Sexually, Volume” I by D. F. Janssen, World Reference Atlas, 2004]

Roth (1908) reports that the Tully river Aboriginals allowed a comparatively old man to sleep with a girl — this was "deemed to make the little girl's genitalia develop all the more speedily". "A girl might grow up big as a result of an incestuous liaison. This is not [something] bad, it is good. [It is] not practised nowadays." (These comments were made by two elderly ladies)." "Rape [...], even of pre-adolescent girls, does occur on occasion. It generally happens when a man takes by force a girl promised to him in marriage".

Yir Yoront

The Yir Yoront (Yir-Yoront) are an Australian Aboriginal people whose traditional lands were situated between 141°45 E and 15°20 S along the Gulf of Carpentaria coast of the Cape York Peninsula in Queensland. This territory encompasses about 1,300 square kilometers (500 square miles) and runs along the coast from the mouth of the Coleman River south through the three mouths of the Mitchell River. The Yir-Yoront now live mostly in Kowanyama (kawn yamar or 'many waters') but also in Lirrqar/Pormpuraaw, both towns outside their traditional lands.[Source: Wikipedia; “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

Yir-Yoront land divisions were based on patrilineal clans, each of which had a swathe of territory segments of which, on the birth of individual clan-members was then assigned to members according to their respective conception totems. Their clan system was composed of two moieties, the Pam-Pip and the Pam-Lul. Pam-nhing were the ancestral beings responsible for both the creation of the world and for the way the group was organized socially. Every site was associated with its ancestral pam-nhing owner, to whom living Yir-Yoront owners were related through the male line.

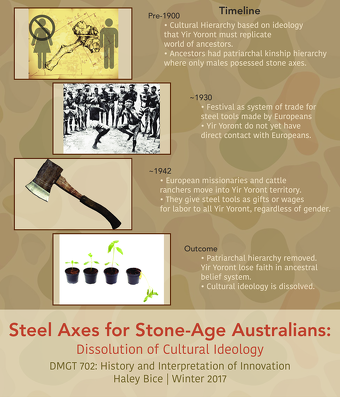

The introduction of steel axes by European missionaries and cattle ranchers into Yir Yoront territory catalyzed a profound shift in cultural ideology among the Yir Yoront people. Prior to this contact, a patriarchal kinship hierarchy dictated the possession of tools, with stone axes exclusively held by males. The dissemination of steel tools, coupled with the dismantling of this hierarchy, led to the erosion of ancestral beliefs and practices, ultimately resulting in the dissolution of their traditional cultural framework.

On their sexual habits, Sharp (1934) wrote: “The sex dichotomy begins early in life [as seen in] obscene and abusive language, in modesty regarding in bodily functions...in childish sexual experimentation, and formally, in the custom for small girls of wearing a pubic apron until the pubic hair appears and an artificial covering is no longer deemed necessary”. [Source: “Growing Up Sexually, Volume” I by D. F. Janssen, World Reference Atlas, 2004]

Guugu Yimithirr — Stingray and Former Dugong Hunters

The Guugu Yimithirr, also spelled Gugu Yimithirr and Gugu Yimidhirr and also known as Kokoimudji are an Aboriginal Australian people that live on the Cape York Peninsula of Far North Queensland, many of whom today live at Hopevale. Guugu Yimithirr is also the name of their language. They were both a coastal and inland people, the former clans referring to themselves as a "saltwater people".

Guugu Yimithirr Aboriginals still hunted dugongs in the 1990s. To kill one, the Aboriginals speared it with a harpoon and then held it against the boat until it drowned. The oil was used relieve aches and the meat they said was very tasty. The Guugu Yimithirr Aboriginals also hunted sea turtles. When a turtle was caught in the old days the Aboriginals used to eat the whole thing, in the 1990s they took the choicest meat and left the rest for the feral pigs. Only Aboriginal are allowed to catch turtles on Thursday Island. A Cypriot explained how he went about hunting the animal there: "We just take a black bloke with us and that makes it legal." [Source: "The Happy Isles of Oceania" by Paul Theroux, Ballantine Books ∝]

Aboriginal peoples in Australia, particularly in Torres Strait and the Wellesley Islands, have hunted dugongs for thousands of years for meat and oil, but the practice is now heavily regulated due to the species' vulnerable status. Historically, dugong hunting involved netting or spearing from rafts. Modern methods include spearing from dinghies with outboard motors, using a harpoon with a detachable head. Traditional knowledge guides sustainable practices, such as conserving pregnant females and ensuring the long-term stability of the dugong population, although poaching remains a concern.

Indigenous peoples of the Torres Strait have harvested dugongs for at least 4,000 years, with evidence of substantial harvesting over the last few centuries. Dugongs hold deep cultural importance, featuring prominently in Aboriginal stories and daily life in the Torres Strait, symbolizing a connection between people and the marine environment.

Dugongs are listed as vulnerable to extinction, and their populations in regions like the Great Barrier Reef are dwindling. About 10,000 dugongs remain in Australian waters. The Aboriginals are allowed to take 100 of them a year. The hunting is allowed is regulated, and some hunters voluntarily avoid killing pregnant dugongs as a conservation measure. Monitoring and Management: Research, including aerial surveys, helps monitor dugong populations and assess the sustainability of the traditional harvest. An illegal meat trade poses a threat, with some individuals disregarding regulations and engaging in "rogue" hunting. Pollution and climate change negatively impact the seagrass habitats essential for dugong survival.

Aborigines in Cape York also hunt stingrays with spears. During the 1930s Aboriginals in northern Queensland earned money by selling sea cucumbers and sea slugs to the Chinese at a time when that country was experiencing a shortage of those creatures. They also exported trochus shells, one of materials used to make buttons before plastic was invented.∝

Wik People

The Wik-Mungkan people are an Aboriginal Australian group of peoples who traditionally ranged over an extensive area of the western Cape York Peninsula in northern Queensland and speak the Wik Mungkan language. Also known as Munggan, Wik and Wikmunkan, they were the largest branch of the Wik people. In early ethnographic accounts of the region, the term "Wik Mungkan" was used to refer both to a specific language and to the "tribe" believed to speak it. Across the area, dialect names typically follow a common pattern: they are formed by adding a prefix meaning "language" (i.e., "Wik-") to a distinctive word characteristic of that dialect. Accordingly, "Wik Mungkan" translates to "those who use mungkan to mean 'eating.'[Source: David F. Martin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

Traditionally, the various Wik-speaking peoples inhabited a broad region of western Cape York Peninsula in northern Queensland, spanning approximately between 13° and 14° south latitude. Their territory included the river systems of the area, the sclerophyll forests between them, and the coastal floodplains along the Gulf of Carpentaria to the west. The coastal zones, in particular, were characterized by significant ecological diversity and pronounced seasonal changes, with a short but intense monsoon season lasting two to three months, followed by a long dry season. |~|

A wide range of dialects were traditionally spoken by groups who identified their language as "Wik Mungkan." Due to the practice of dialect exogamy—marrying outside one's own clan or village—multilingualism was common, especially in the coastal regions. However, over time, and due to complex social and political changes, many of these original dialects are no longer spoken. In contemporary communities, Wik Mungkan and Aboriginal English have emerged as the primary lingua francas.

See Separate Article: WIK MUNGKAN PEOPLE OF NORTHERN QUEENSLAND: HISTORY, CUSTOMS, LIFE ioa.factsanddetails.com

Butchulla People of Fraser Island

The Butchulla people, custodians of K'gari (Fraser Island), have a deep connection to the island spanning potentially 50,000 years Their culture is characterized by a balance of spiritual, social, and family connections, maintained through harmony with the natural world. Butchulla is also written Butchella, Badjala, Badjula, Badjela, Bajellah, Badtjala and Budjilla. [Source: Wikipedia]

The Butchulla spoke Badjala, considered to have been a dialect of Gubbi Gubbi. In the 1800s, there were reported to be 19 groups that lived on the island permanently, with the island split into three sections. The people in the northern part of the island (Ngulungbara) were a separate group from the other two and did not want to be associated with the Badjala people, when they were pressed into the same mission. The people of the lower part of the island (Dulingbara) also moved along the coast line to Noosa area. All three groups – Ngulungbara, Butchulla and Dulingbarra – seem to have spoken dialect variations of Gubbi Gubbi.

Fraser Island's abundance of fish resources made it rank, with the Kaiadilt homeland of Bentinck Island, as one of the two most densely populated areas on the Australian continent. The island began to be occupied by white people in 1849. At that time, the Indigenous population of the 19 clans was estimated to be around 2,000. Within three decades (1879), their numbers had dropped to around 300–400, a collapse attributed by an informant of the then Chief Commissioner of Brisbane to shootings by the Australian native police, and the effects of venereal disease and alcohol introduced by white people.

Kuku Yalanji of the Daintree Rainforest

The Kuku Yalanji people of the Daintree Rainforest north of Cairns are known for their deep ecological knowledge and cultural practices like dreamtime walks. Their traditional lands stretch from the rainforest regions of Mossman, Daintree, and Bloomfield River, across to the mountain ranges and coastlines. Kuku Yalanji is also spelled Kuku Yalangi and Guugu Yalandji. Kathy Freeman, who won the gold medal in the 400 meters, at the 2000 Olympics and was one of the most memorable figures at those Olympics, is Kuku Yalanji

The Kuku Yalanji numbered around 3,000 people in 2003. ,The Kuku Yalanji are often called the "rainforest people" because their country covers the Wet Tropics UNESCO World Heritage area. They have a deep cultural and spiritual connection to the rainforest, rivers, reefs, and coastal ecosystems. Their language is also called Kuku Yalanji, part of the Pama–Nyungan language family. "Kuku" means "speech" or "language," so "Kuku Yalanji" translates to "language of the Yalanji people."

The Kuku Yalanji have rich traditions of bush foods, rainforest medicine, and seasonal knowledge. Dreaming stories connect people, plants, animals, and landforms. Art and body painting often use designs that represent land and ancestral beings. They traditionally lived in gunyahs — small, temporary shelters made of branches and bark also known as humpies. Their staple foods were the toxic seeds of Cycas media, which were leached of their poisonous compounds before cooking, along with two species of yam, with the variety known as bitter yam particularly sought after, bitter walnuts, candlenuts and Kuranda quandong.

Early reports described the Kuku Yalanji as cannibals who were said to be particularly fond of eating Chinese immigrants, whom they called kubara[a] or miran bilin (tight eyes). There were also reports of them eating of parts of the dead, which however was a restricted practice related to ritual mortuary customs. Descriptions of them killing their own women and children when food was in short supply and "feasting" on Chinese like "manna from heaven" in popular works like that of Hector Holthouse are are now considered wild exaggerations.

Arrernte

The Arrernte are also known as Aranda and Arunta. They are an Aboriginal Australian peoples of Central Australia, with their lands centered around Alice Springs (Mparntwe) in the Northern Territory. They are the traditional owners of the desert region they live in and are known for their rich cultural heritage, including their spiritual beliefs, languages, art, and totemic systems. In the old days, their territory extended into Queensland but not so many live there any more.

Arrernte and Aranda refer to a language group and a people. "Aranda" is a simplified, Australian English approximation of the traditional pronunciation of the name of Arrernte. Arrernte culture is expressed through ancient stories, rituals, and art, which are passed down through generations. Religious life was a significant aspect, with major gatherings held to conduct ceremonies and rituals. The concept of the Dreaming is central to Arrernte beliefs, representing a time of ancestral beings and the origin of life. While some Arrernte people still live in their traditional lands, others have moved to towns, major cities, or overseas. Efforts like "Aranda Tribe Ride for Pride" are underway to revitalize and teach Arrernte languages, which are considered vulnerable, and strengthen of community pride and the importance of passing on cultural knowledge,

Arrerntic and Arandic groups have traditionally been distributed throughout the area of the Northern Territory, Queensland, and South Australia between 132° and 139° S and 20° and 27° E. Their territories were concentrated in the comparatively well-watered mountain areas of this desert region, though several groups—especially along the northern, eastern, and southern edges of the Arrernte-speaking area—also occupied vast sandhill country. [Source: John Morton, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

The estimated number of Arrernte people (and speakers of Arrernte languages) is around 3,000. The number of people with the Aranda surname is 2,605 individuals recorded in Australia's 2021 census data. The total population of Aranda speakers in precontact times was probably not over 3,000. The population fell very sharply after the arrival of white people, mainly as a result of the introduction of new diseases. At the present time the total population of Arrernte is rising, although the spatial and cultural distribution of the population has shifted dramatically. Major settlements at or near Hermannsburg, Alice Springs, and Santa Teresa account for the bulk of the Arrernte population. |~|

See Separate Article: ARRERNTE: HISTORY, LANGUAGE, TRADITIONAL LIFE, CUSTOMS ioa.factsanddetails.com

Torres Strait Islanders

Torres Strait Islanders are a people of Melanesian descent who inhabit the islands between northeast Australia Queensland and Papua New Guinea. They are culturally and ethnically distinct from Australia's Aboriginal peoples, with their own languages and traditions. Known as skilled seafarers, farmers, and traders, Torres Strait Islanders preside over a rich, vibrant culture that includes traditional art, dance, and songs that are passed down through generations. In many ways they are more similar to the people of New Guinea than Aboriginal Australians.

Torres Strait Islander culture is centered around the sea, with traditional navigation, fishing, and trading forming a big part of their traditional life but they also practice agriculture. The islands have been inhabited for thousands of years but sustained European contact began only in the mid-19th century, with significant impacts from the pearl shell industry. Their art includes sculpture, printmaking, and mask-making. The islands and their inhabitants are among the most famous of ethnographic subjects as a result of the Cambridge University expedition of 1898, organized and led by A. C. Haddon.

Named after its Spanish discoverer, Captain Luis Baez de Torres, who first explored the region in 1606, the Torres Strait connects the Coral and Arafura and is situated between the southwestern coast of Papua New Guinea and Australia's Cape York. Of the more than 100 islands in the strait, only about 20 have ever supported permanent populations; the remainder are too small or lack the resources necessary for long-term habitation. The inhabited islands fall into four basic physical types. The Western Islands are large, elevated, and well-watered, their shorelines lined with mangrove swamps. The Central Islands are low sand cays formed on coral reefs. The Eastern Islands are small volcanic outcrops with fertile soils. To the north, close to the coast of Papua New Guinea, lie large, low-lying islands dominated by mangrove vegetation, which are fertile but prone to frequent flooding.[Source: Nancy E. Gratton, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

See Separate Article: TORRES STRAIT ISLANDERS: HISTORY, TRADITIONAL LIFE, CULTURE ioa.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Culture Shock! Australia, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated September 2025