Home | Category: Aboriginals

YOLNGU

Yolngu men participating in bunggul at the 2023 Garma Festival, from National Indigenous Times

The Yolngu are a group of Aboriginal Australians that reside in northeastern Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory of Australia. Yolngu means "person" in the Yolngu languages. In the past anthropologists used the terms Murngin, Wulamba, Yalnumata, Murrgin and Yulangor for the Yolngu. They were also known as Miwuyt and Yuulngu. Wulamba was a Cultural Bloc. All Yolngu clans are affiliated with either the Dhuwa (also spelt Dua) or the Yirritja moiety (divided social-ritual group). Prominent Dhuwa clans include the Rirratjiŋu and Gälpu clans of the Dangu people, while the Gumatj clan is the most prominent in the Yirritja moiety. [Source: Wikipedia]

Yolngu is the word for "Aboriginal human being" in all the dialects. Aboriginal people in the Yolngu-speaking area refer to themselves as yolngu (as well as identifying all Aboriginal Australians as yolngu). Within the Yolngu area are some twenty such language-named, land-owning groups. In addition to the names of Language groups, Yolngu people describe and name themselves in a number of other ways, including the location and features of the land they own or where they live (for example, "beach people" or "river people"). [Source: Nancy M. Williams, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

The population of Yolngu people is spread across the East Arnhem region. Some sources count 5,000 Yolngu in North-East Arnhem Land, and approximately 12,000 overall . The Aboriginal population within the Yolngu area was estimated at 3,500 in the 1999s. The main population centers are developing towns and settlements that were formerly Protestant missions. The Yolngu area is roughly triangular and is located between 11° and 15° S and 134° and 137° E. The northern and eastern "sides" are coastal and the third "side" runs inland southeast from Cape Stewart on the north to south of Rose River on the east. Northeastern Arnhem Land is monsoonal, with northwest winds bringing rain during the Wet from about December until April or May.

Yolngu languages are classified as Pama-Nyungan along with others covering seven-eighths of Australia, but they are isolated geographically from other Pama-Nyungan languages. Yolngu speakers classify their Languages according to their pronominal systems into some nine groups, and each group is labeled by their shared demonstrative "this/here." Two of the largest groups, in terms of number of named languages, also classify their speakers by moiety: dhuwal languages are all Dhuwa moiety , and dhuwala Languages are all Yirratja moiety . Since the 1970s and the Development of adult education and bilingual education programs, a substantial amount of written material is being produced in the Yolngu languages.

RELATED ARTICLES:

ABORIGINALS (FIRST NATION PEOPLE) OF AUSTRALIA: NAMES, DEMOGRAPHICS, LANGUAGES ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIANS IN NORTH NORTHERN TERRITORY: SOME GROUPS, CUSTOMS, LIFESTYLE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL ART OF NORTHERN AUSTRALIA: ANCIENT ROCK ART AND BARK PAINTINGS ioa.factsanddetails.com

TIWI PEOPLE OF NORTHERN AUSTRALIA: HISTORY, CUSTOMS, TRADITIONAL LIFE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS IN QUEENSLAND: SOME GROUPS, CUSTOMS, LIFESTYLES ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS OF CENTRAL AUSTRALIA: SOME GROUPS, CUSTOMS, ART, LIFESTYLE ioa.factsanddetails.com

EARLY MODERN HUMANS IN AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

LIFE OF EARLIEST HUMANS IN AUSTRALIA: TOOLS, WEAPONS, ART, SETTLEMENTS ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINALS AT THE TIME EUROPEAN COLONIZATION BEGAN ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIA ABORIGINALS FROM 1900 TO PRESENT: DISCRIMINATION, ASSIMILATION, SOME RESTITUTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIA’S STOLEN GENERATIONS: VICTIMS, LAWS, RATIONALE, OUTRAGE ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL RELIGION: TRADITIONAL BELIEFS, DEMOGRAPHY AND DEATH ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL CUSTOMS, SOCIETY AND RITUALS ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL LIFE: WHERE THEY LIVE, WORK, DIET, HEALTH, ALCOHOL ioa.factsanddetails.com

TRADITIONAL ABORIGINAL LIFE: FOOD, HOMES, HUNTING ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL MEN AND WOMEN: GENDER, MARRIAGE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIAN SEX: PRACTICES, ATTITUDES, ADOLESCENCE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIAN ART ioa.factsanddetails.com

Yolngu History

Northeast Arnhem Land, home of the Yolngu, from Culture College

In Western Arnhem Land, an area west of the Yolngu, archaeologists have excavated several sites of human habitation dating back more than 50,000 years, with one possibly being 65,000 years old. The Yolngu have likely inhabited northeastern Arnhem Land for a similar amount of time. The Yolngu had sporadic contact with non-Aboriginal people until the European occupation of the Northern Territory began in the late nineteenth century. The only exception was the regular visits of Makassans, traders from Sulawesi, who gathered bêche-de-mer annually from the late seventeenth century until 1907. The Yolngu helped the Makassans gather and process the bêche-de-mer and obtained iron tools, cloth, tobacco, and dugout canoe construction techniques from them. [Source: Nancy M. Williams, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

In earlier times, blood revenge (or payback) was a prevailing custom: certain kinsmen of a deceased person were obligated to avenge the death. Since few deaths were attributed to “natural” causes, people were often either preparing a revenge expedition or fearful of becoming its target. It has sometimes been claimed that disputes among the Yolngu—and Aboriginal people more generally—arose only over women or corpses. The Yolngu, however, reject this view, maintaining that serious conflicts are primarily about land. The "makarrata", often described as a “peace-making” ceremony or a “trial by ordeal,” represents a ritualized form of revenge. Its successful completion is marked when blood is drawn from a wound to the thigh of the principal offender, a symbolic act that balances the account—at least for the duration of the ceremony. Another custom, known as mirriri, concerns special avoidance behavior between brothers and sisters (See Kin Relations Below) . Any reference to a woman’s sexuality made in her brother’s presence obliges him to attack her or any other woman he regards as a sister. Today, while physical attacks with spears no longer occur, people remain highly cautious about making such references in front of a brother.

In the nineteenth century, explorers and prospectors began making their way overland, while government customs boats patrolled the coast. The Yolngu area is included in the Arnhem Land Aboriginal Reserve, which was created in 1931. Hostilities involving Japanese bêche-de-mer collectors and a police expedition in 1932 led to the establishment of a mission station on the Gove Peninsula. The station was intended to serve as a buffer between the Yolngu people and the increasingly frequent incursions of non-Aboriginals into the area. Other missions had been established earlier: two on the north coast and one on the south coast. Each of these missions became centers of a gradually increasing Yolngu population. During World War II, some Yolngu were killed in Japanese air attacks. Some served in an Australian unit in Dutch New Guinea, and many became acquainted with Europeans.

After World War II, an increasing number of missionaries and government personnel were stationed in Yolngu settlements, and efforts to implement the federal assimilation policy intensified. Although the Yolngu were gradually accepting Christianity, they generally resisted complete assimilation into the dominant British-derived society. In 1976, federal governments that supported multiculturalism and Aboriginal self-determination enacted land-rights legislation (which made the Arnhem Land Reserve an inalienable freehold, also called "Aboriginal Land") and began to support a widespread decentralization movement as the Yolngu started to move back to their traditional lands. Although the number of settlements established there is increasing and they are intended to be permanent, they remain attached to and serviced by the larger towns (formerly missions). The Yolngu people are committed to developing economic independence, though it must be based, to some extent, on mining their land, which they object to in principle. They are also committed to developing a bicultural society at a rate of change under their control.

Yolngu Traditional Religion and Mythology

Yolngu religious beliefs center on myths about the travels and activities of spirit beings in the beginning of time. The Earth was much as it is now, but the actions of these beings set the patterns of proper behavior for future Yolngu and left signs of their presence in the land. "Wangarr" refers to both spirit beings and the distant past. It is comparable to the concepts of "the Dreaming" or "the Dreamtime" in other Aboriginal religions. The concept of Wangarr (also spelled Wanja or Waŋa) is complex. Attempts to translate the term into English have referred to the Wangarr beings as "spirit man/woman," "ancestor," "totem," or various combinations thereof. [Source: Wikipedia, Nancy M. Williams, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

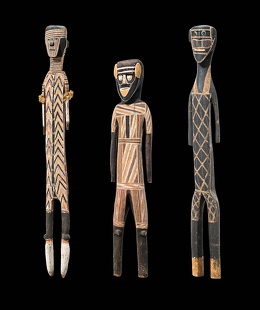

Representational mortuary figures of Mokuy (Sinister or Shadow Spirits) made in North-Eastern Arnhem Land

The Yolngu believe that the Wangarr ancestors not only hunted, gathered food, and held ceremonies as they do today, but also created plants and geographical features, such as rivers, rocks, sandhills, and islands. These features now embody the essence of the Wangarr. The Wangarr also named species of plants and animals and made them sacred to the local clan. Some Wangarr took on the characteristics of a species, which then became the clan's totem. Sacred objects and designs are also associated with Wangarr. They gave clans their language, law, paintings, songs, dances, ceremonies, and creation stories.

The Wangarr ancestors bestowed the land and performed ceremonies that the present-day landowners should perform. During their journey, they transformed parts of the landscape. At a clan's most important sacred site, they left part of themselves behind. In some cases, they stayed and are still there. The Yolngu believe that the Wangarr continue to exist and manifest themselves in both the seen and unseen worlds. The most important ones for individuals are those of their father's and mother's clans. Healers (marrnggitj) have spirit familiars, often referred to as their "spirit children," who assist them in their healing practices. Since the arrival of the missions, all Yolngu have some knowledge of Christianity, and to varying extents, they have become active church members.|~|

Since all Yolngu are expected to participate in religious rituals, and most do, they are all practitioners. Men sing ritual songs and perform the appropriate dances, and women perform the dances required for certain phases of Ceremony. Traditional ritual specialists are men who memorize a large body of sacred names, sometimes called "power names." These names refer to clan lands, sites, spirit beings, and their attributes. The specialists intone these names as invocations at certain points in the ritual. Some Yolngu men have been ordained as ministers in the Uniting Church, the successor of the original Methodist mission church. For most Yolngu, it is important that their Christianity has been Aboriginalized. Some Yolngu ceremonies and sacred objects have been incorporated into the iconography of Yolngu Christian churches.|~|

Death and Afterlife At the time of death, the soul—or its malevolent aspect—remains near the place of death and poses a threat to close family members. One objective of the purificatory rites performed to "free" survivors and material objects associated with the deceased, including houses, is to protect against the malignity of the soul. Throughout the mortuary ritual, which can last for an extended period of time, the soul is guided to a specific area or site on its clan's land. There, it awaits reincarnation alongside the souls of its clan.

Yolngu Marriage and Family

Yolngu women participating in bunggul at the 2023 Garma Festival, from National Indigenous Times

Polygynous marriages were once considered the most desirable, but now are rare. Moiety (each of two parts of a divided thing) and clan exogamy (marrying outside a village or clan) are observed. Within these parameters, families arrange marriages. Ideally, a young man is assigned a mother-in-law who is his mother's sister's daughter (most likely and desirably, a classified relative in this category). Historically and to a large extent today, marriages maintain or extend alliances between lineages. A young man performs bride-service. Although divorce was not formally recognized, permanent separation of spouses was not uncommon. [Source: Nancy M. Williams, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

Traditionally, a man and his wife (or wives, who are often sisters), and their children ate and slept together, whether they lived in houses in towns or in shelters at homeland centers. Brothers and their families often lived in close proximity. Women in such households foraged together, and brothers often hunted together. |~}

Infants are almost always in physical contact with their caregivers, children are never physically punished or threatened by adults, and infants and young children are never openly denied anything they want. The Yolngu advocate for bicultural education, also known as "two-way education," and some are designing school curricula, and administering and teaching in their own schools. A number have university degrees.

In terms of inheritance, joint rights in land inhere in the patrilineal (based on descent through the male line) group into which each person is born. Similarly, ownership of a language is inherited. A lineage is a potential inheritor of land belonging to the patrilineal group of a real or classificatory maternal grandmother, should there be no remaining males in that group. Movable property is disposed of through exchange. In the past, a deceased person's personal property was destroyed. Now, if the property is valuable, it is ritually purified and distributed to relatives based on their attachment to the deceased. |~|

Traditional Yolngu Sex Practices and Beliefs

According to “Growing Up Sexually: The Yolngu practiced prenatal betrothal and, together with eventual siblings, joined the husband at menarche (first menstrual period in a female adolescent), at age 12 or 13. “Should a girl be taken prepubertally by her older promise man (in lieu of a bride price), then sex with her would be confined to his training her vagina in digital masturbation (“finger-dala”), until after the age of menarche (when a girl has her first period). Only then would penile intromission begin”. Warner (1937) reported the Yolngu believed “menstruation is due to the sexual act”. Hamilton (1981) reported of the neighbouring Anbarra people that all female informants agreed “no girl could “get blood” until a man had helped her by copulation”. [Source: “Growing Up Sexually, Volume” I by D. F. Janssen, World Reference Atlas, 2004]

Young Yolngu men participating in bunggul at the 2023 Garma Festival, from National Indigenous Times

Money et al. (1970), on the Arnhem Land Yolngu, questioned that children learned from parents, except by chance; in fact, no sex education would be given. Instead they learn from “children scarcely older than themselves” up to teens spied in the bush. The “coital play” of four- to six-year-olds is performed in the context of playing house, and involves thrusting motions...possibly with the use of intromission of a finger or stick. During middle childhood, “children may sometimes engage in sexual play. Heterosexual play is unlikely, and so is homosexual play between boys. The sexual play between girls is not unambiguously “homoerotic”, for it occurs as an improvisation in a game of house. When the time comes for the mother and father to have intercourse, then one girl improvises a penis with a piece of a stick, and puts it in the vagina of the other”. Thus, “children’s play may include rehearsal of copulation, though childhood sex is not an unostentatious feature of the culture”. Young (prepubertal) boys would take the feminine role in interfemoral intercourse with older, “rebellious” adolescents

On house-playing among the Yolngu, Warner (1937) noted: “They are fully aware of the sexual act and of sex differences. About the time facial hair appears upon a boy and the breasts of a girl swell, that is, when sexual intercourse is in their power and of interest to both, they start making love trysts in the bush. They may not copulate at first, but they simulate the act in close contact”. A forty-five year old man reveals of his childhood.

When we little boys and girls played together we did it by ourselves so that no one could see. We were ashamed if we thought older people were watching and listening to what we were doing. We said things to each other about sexual intercourse and other sexual things which we did not understand. The other day I heard a little girl say to the little boy she was playing with, “You are my husband. I am your wife. Come have sexual intercourse with me”. That was the kind of thing we said to each other. I laughed because I remembered when we said those things and we did not know what they meant. She said it because it was part of their game. But when we grew larger we did find out and some of us became sweethearts”.

Equally, Hippler (1978) stated that among the Yolngu, “the child is sexually stimulated by the mother...Penis and vagina are caressed...clearly the action arouses the mother. Many mothers develop blissful smiles or become quite agitated (with, we assume, sexual stimulation) and their nipples apparently harden during these events. Children...are encouraged to play with their mothers’ breasts, and...are obviously stimulated sexually”. Money and Ehrhardt (1973) add: “In former times infants might be pacified by fondling of their genitals, but this practice is not obvious today”.

Yolngu Towns and Economic Activity

The population of the four major Yolngu towns, called "townships," ranges from 1,000 to 2,000 people. This includes permanent and semi-permanent residents of outstations and homeland centers serviced by the towns. The towns reflect their origins as missions, with a central area containing administrative buildings, a church, and substantial, well-constructed houses. Nearby, sometimes in the center and sometimes radiating away from it, are the homes of the Yolngu people. [Source: Nancy M. Williams, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

Initially, housing consisted of traditional, seasonally appropriate shelter designs. Later it was made of bush timber and corrugated iron, and later still, framed corrugated iron on a cement slab was used. In recent decades houses have increasingly been built closer to standard Australian outback designs, and more recently, they are being built with cement blocks. At the homeland centers, construction predominantly uses bush timber or corrugated iron with earth or sand floors, though some "kit houses" are now being erected. The largest center in the Yolngu area is the mining town of Nhulunbuy, which has an estimated population of 3,500, fewer than 50 of whom are Yolngu. In the other centers, non-Aboriginal residents comprise about eight percent of the population and are mostly employees of Yolngu towns and organizations.

Traditionally, women gathered and processed plant foods and also supplied significant amounts of protein—shellfish along the coast and small animals such as goannas and snakes in inland areas. Men, in contrast, hunted less frequently but secured highly valued large game: turtles, dugongs, and fish on the coast, and kangaroos, wallabies, emus, opossums, bandicoots, and echidnas inland. This division of labor persists today, though both women and men now line-fish, while men continue to use spears and spear-throwers. In wage and salary work, however, the division of labor follows the Euro-Australian model.

The Yolngu economy relied solely on hunting and gathering until the establishment of the missions and the gradual introduction of market goods in the mid 20th century. Even though motor vehicles, aluminum boats with outboard engines, guns, and other introduced objects have replaced indigenous tools, hunting and gathering is still part of Yolngu in terms of both subsistence (especially at the homeland centers) and identity. Small amounts of cash were introduced in the 1940s and 1950s, and by 1969, federal training grants were providing limited wages and social service benefits. By the mid-1970s, standard wages were in place, but social services remain the major source of cash income for Yolngu, and unemployment (by European-Australian standards) remains over 50 percent. Most employment is provided by government agencies in administrative and service jobs. Yolngu on the Gove Peninsula have established business enterprises mainly related to contract work for the mining company. ~

Yolngu Foods, Drinks and Medicine

Yolngu food consists of various traditional bush foods, including bush fruits like green plum and noni fruit, sea foods such as longbums (mud mussels) and trepang (sea cucumbers), small game, and native plants, with varies seasonal and geographical variation. Traditional practices include increase rituals to ensure food abundance and a deep cultural connection to the land through food. While traditional foods are still valued, the modern Yolngu diet is increasingly influenced by store-bought foods, leading to high sugar consumption. There is an active effort to promote traditional bush foods as a way to improve nutrition and support cultural well-being, with programs like Zach Green's Elijah's Kitchen pop-up restaurant highlighting these foods and their significance for reconciliation, according to ABC.

Traditional bush foods fruits include GREEN plums, noni fruit (blue cheese fruit), wild passionfruit, wild oranges, and bush tomatoes. Among the seeds and nuts consumed are mulga seeds, wattle seeds, and pandanus nuts. The Yolngu people harvest various marine resources, including longbums (mud whelks), stingray, and trepang, which have historically been traded with Makassan traders. Small game mammals such as wallabies, and birds, are hunted.

Water (gapu) is a central symbol in Yolngu culture and metaphorically linked to kinship and the human body. Gapu symbolizes the flow of water, from the dry season to the monsoonal floods, drawing parallels to Yolngu kinship systems and the human body. Way-a-linah is a traditional alcoholic beverage made by indigenous Australians from fermented tree sap, described as a cider-like drink.

Today, the Yolngu make use of Western medical services but may also consult a marrnggitj for diagnosis or treatment, particularly when illness is believed to stem from sorcery or from accidental intrusion into a spiritually dangerous place. In addition, the Yolngu maintain an extensive pharmacopoeia based largely on native plants, with most people possessing at least some knowledge of their preparation and use.

Yolngu Kin Groups and Land Tenure

The main corporate kin groups are patrilineal (based on descent through the male line) clans that own land and the ritual objects and ceremonies that validate their title. n larger clans, this role may be taken on by subclans or lineage groups. Kinship serves as the central framework of social identity in the Yolngu world: every individual is regarded as kin to all others, with connections traceable through multiple lines of relationship. Matrilineal (descent through the female line) defined relationships establish rights and duties complementary to those of patrilineal descent (through the male line) but not corporate landowning groups. [Source: Wikipedia; Nancy M. Williams, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

The Yolngu people use twenty-four kin terms, as well as some optional extras, to distinguish between marriageable and nonmarriageable relatives, as well as between lineal and collateral relatives. The term yothu-yindi, after which the band is named, literally means "child-big one" and describes the special relationship between a person and their mother's moiety, which is the opposite of their own. Due to yothu-yindi, the Yirritja have a special interest in and duty toward the Dhuwa, and vice versa. For instance, a Gumatj man may craft the varieties of yiaki associated with his clan group and his mother's clan group. The Yolŋu languages have a word for "selfish" or "self-centered": gurrutumiriw, which literally means "kin-lacking" or "acting as if one has no kin."

As with most Aboriginal groups, Yolngu culture includes avoidance relationships between certain relatives. The two primary forms are: 1) between a son-in-law and his mother-in-law, and 2) between a brother and sister. Brother–sister avoidance, known as “mirriri”, typically begins after initiation. In such relationships, individuals refrain from speaking directly, avoid eye contact, and try not to remain in close physical proximity.

Land is owned by language-named clans. The parcels that comprise a clan's estate do not necessarily have to be contiguous; ideally, they include both coastal and inland areas. Individuals inherit ownership rights in the clan estate from their father, as well as responsibilities and use rights in their mother's estate. They may also have subsidiary rights in the area where they were conceived (where their father found their spirit before it entered their mother) and where they were born. Additionally, individuals have interests in and responsibilities for their maternal grandmother's estate, including the potential right of inheritance should there be no males in their maternal grandmother's clan. In 1976, federal legislation formally recognized Yolngu title, along with the Aboriginal title of all Aboriginal reserve land.

Yolngu Rituals, Festivals and Ceremonies

For the Yolngu, the most significant ceremonies are those surrounding death. Mortuary rituals are highly elaborate and deeply meaningful, though they have been reshaped in certain ways since the arrival of the missions. The early stages of initiation into ritual manhood were often incorporated into these ceremonies, when sacred paraphernalia were renewed and the appropriate kin had gathered. Such gatherings also served as opportunities to arrange marriages, conduct trade, and negotiate other matters, and were usually held at the end of the dry season. The most restricted ceremonies are those in which a clan’s sacred objects are redecorated, displayed, and their meanings explained. Directed by senior men, these rites admit only mature men who have demonstrated their readiness, with knowledge revealed gradually and in stages. The sacred objects themselves hold immense significance for the Yolngu, sometimes referred to as “title deeds” to land, reflecting their fundamental role in identity, authority, and connection to country.[Source: Nancy M. Williams, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

The Garma Festival is Australia’s largest Indigenous gathering, a 4-day celebration of Yolngu life and culture held in northeast Arnhem Land. Hosted by the Yothu Yindi Foundation, Garma showcases traditional miny’tji (art), manikay (song), bunggul (dance) and story-telling, and is an important meeting point for the clans and families of the region. The Festival’s over-riding cultural mission is to provide a contemporary environment for the expression and presentation of traditional Yolngu knowledge systems and customs, and to share these practices in an authentic Yolngu setting. Participants camp on the sacred Gulkula site and follow strict cultural protocols throughout the event. [Source: Yothu Yindi Foundation]

Bunggul: Each sunset, accompanied by the call of the yidaki (didgeridoo), and the rhythm of the bilma (clapsticks), the voices of the Yolngu song-men ring out across the site, summoning all to the dance grounds. Here, the men, women and children of the different clan groups take turns performing traditional dance (bunggul), sharing stories and songlines that stretch back millennia. Bunggul(or buŋgul) are important ceremonial events where Yolngu songmen share stories and customs. A buŋgul is a gathering ground for dance, song, and ritual. It serves as a meeting point for Yolŋu clans and families.

Yolngu Art

Several Yolngu towns and outstations are well known for producing arts and crafts that also provide an important source of income. These include bark paintings, wood carvings (primarily made by men, though not exclusively), and woven net bags and baskets (produced exclusively by women). Yolngu women in particular weave dyed pandanus leaves into baskets, while necklaces are fashioned from seeds, fish vertebrae, or shells. Colors often signify the origin of an artwork, identifying the clan or family group responsible for its creation. Certain designs serve as emblems of particular families and clans. [Source: Wikipedia; Nancy M. Williams, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

Men learn to paint figures and designs that represent their clan's heritage, as well as the heritage of their mother's clan. They paint these designs on bodies during religious ceremonies and, currently, on sheets of prepared bark as commercial fine art. Since the 1970s, women have also produced commercial fine art. In Yolngu homes, bark paintings and carvings are displayed for their aesthetic value as well as their religious significance.

Before the Western Desert art movement emerged, Yolngu bark paintings, characterized by intricate cross-hatching, were the most widely recognized form of Aboriginal art. Hollow logs, known as larrakitj, are used in Arnhem Land burial practices and hold deep spiritual significance. They also serve as important canvases for Yolngu artistic expression. One of the most famous examples is David Malangi Daymirringu’s bark painting depicting the Manharrnju clan's mourning rites. The painting is from a private collection. This work was reproduced on the original Australian one-dollar note without the artist's knowledge. When the copyright infringement was discovered, the government, with the help of H. C. Coombs, acted quickly to compensate the artist.

Yolngu Music and Dance

Yolngu artists and performers are leaders in bringing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture to a wide audience. Traditional Yolngu dancers and musicians have performed internationally, and through the influence of prominent families such as the Munyarryun and Marika, they have had a formative impact on contemporary performance groups, including the Bangarra Dance Theatre. Performance of ritual is judged by canons of aesthetics which make it a form of art as well as religious practice; Individual dancers, singers, and drone pipe players are noted and praised for their performance style. For More on Dance See Bunggul Under Festivals Above [Source: Wikipedia; Nancy M. Williams, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

Arnhem Land is the home of the yi aki, which Europeans have named the didgeridoo. Yolngu are both players and craftsmen of the yi aki. It can only be played by certain men, and traditionally there are strict protocols around its use. Highly regarded didgerdoo players include Joe Geia, Charlie McMahon and Mandawuy Yunupinu of Yothus Yindi.

Geoffrey Gurrumul Yunupingu (1971–2017) was a famous Yolngu singer, formerly a member of Yothu Yindi. Blind and known for his sweet voice, he released his first solo album Gurrumul in 2008, which was a hit in Australia and won several awards. He is a self-taught musician who worked extensively with white producer Michael Hohnen, creative director of Skinny Fish Music. According to “CultureShock! Australia”: Yunupingu’s tech-free acoustic guitar work (played left-handed) and his haunting voice, often combined with Western classical support instruments, have been hailed as a unique cultural bridge between settler and indigenous Australia. Former musician and minister Peter Garrett told The Weekend Australian in 2008, that Yunupingu’s song ‘Djarimiiri’ was ‘chock full of soul and melody, unadorned by technological fetishism’, no exaggeration. Yunupingu’s compositions are soaked in his cultural background in remote Arnhem Land, sung in his own language, and yet have a musical form that speaks to a diversity of audiences. [Source: Ilsa Sharp, “CultureShock! A Survival Guide to Customs and Etiquette: Australia”, Marshall Cavendish, 2009]

Yothu Yindi

The most well-known Aboriginal bands and one of the biggest Australian bands in the 1990s was Yothu Yindi — made up of Yolngys musicians from Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory. "Yothu" means child and "yindi" means mother in the Aboriginal language from that area. Their biggest hit, "Treaty," is a song calling for a formal treaty between black and white Australian co-written with Paul Kelly and Peter Garret of Midnight Oil.

Yothu Yindi received a lot of international attention in the early 1990s, and was described by Billboard magazine as "the flagship of Australian music." The groups was found by Mandawuy Yunupingu and Witiyana Marika, sons of leaders of the Gumatj and Rirratjingu clans in Arnhem Land and members of families who have been in involved in the Aboriginal rights movement.

Yothu Yindi had nine Aboriginal and two white Australian members in 1995 who played guitar, drums, bass, keyboards, didgerdoos, and bilmas. They often appeared live with body-painted dancers and include traditional songs in their shows. The group released their first album “Homeland Movement” in 1988. This was followed by “Tribal Voice” and “Freedom”. In 1993, Yunupingu was named "Australian of the Year" for his efforts to bring Aboriginals and whites together.

The lyrics to “Treaty” go:

“Words are easy, words are cheap

Much cheaper than our priceless land

But promises can disappear

Just like writing in the sand.

Treat Yeh, Treaty Now,

Treat Yeh, Treaty Now.”

Yolngu Social and Political Organization

The Yolngu are citizens of Australia, subject to both Commonwealth and Northern Territory law. At the same time, they hold a special status through legislation defining “Aboriginal land” and the limited recognition of elements of customary law. Yolngu towns receive financial support for infrastructure and development either from federal funding authorities or the Northern Territory government, depending on the legislation under which they are incorporated. [Source: Nancy M. Williams, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

Yolngu society is organized around principles of descent, with kinship serving as the primary framework through which categories and groups are related. Age (both absolute and relative), birth order, and gender also play important roles in shaping social organization. Central to Yolngu life is a pervasive dualism expressed in the division of the universe into two complementary moieties, Dhuwa and Yirritja. Every individual belongs by birth to the moiety of their father. Each named clan is aligned with one of the two moieties: clans of the same moiety are linked through shared myths, while clans of opposite moieties are bound together through marriage alliances. Clans or particular lineages connected through matrifiliation across alternate generations are closely associated—sometimes effectively merged—through shared rights in land and ritual performance. Within this framework, Yolngu place a high value on personal autonomy and individual achievement.

Leadership within Yolngu society is primarily determined by seniority, which follows birth order. The eldest man in a sibling set is expected to exercise authority over his brothers, sisters, and their families. Likewise, the eldest man of a clan should be its head, with his next-younger brother serving as his deputy. This principle of seniority tempers the strict ranking of lineages; in practice, if the heir apparent is deemed too young to lead, a younger brother of the deceased leader will often assume headship. This system, however, provides grounds for competition over leadership. Importantly, the rule of seniority applies to both men and women, though in public contexts authority is usually exercised by men. In Yolngu politics, birth order often outweighs gender as a determinant of authority.

Effective leaders are expected to be skilled orators and to take responsibility for “looking after” all who recognize their authority. Decision-making is consensus-based: until agreement is reached, no decision is considered final. These principles continue to shape Yolngu political life, even as elected councils now manage town administration. Yolngu have also become increasingly active in Northern Territory politics, both through the Northern Land Council and in direct engagement with government. Yolngu men have served as an elected Member of the Northern Territory Legislative Assembly.

A central responsibility of Yolngu leaders is the management of dispute settlement. When grievances arise, a leader may intervene directly, convene family meetings, or call clan moots to involve all those whose agreement is required to resolve the matter. Disputes may be made public through loud, open declarations of grievance, sometimes accompanied by threats of violence. In such cases, specific kin are expected to act immediately: sisters or brothers-in-law to physically restrain the aggrieved party, and lineage leaders or clan heads to restore calm and undertake to arrange a satisfactory resolution.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Culture Shock! Australia, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated October 2025