Home | Category: History / Aboriginals

AUSTRALIA ABORIGINALS IN THE 20TH AND 21ST CENTURIES

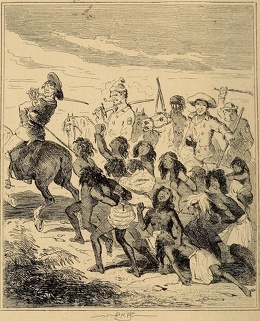

When the British arrived in Australia, they declared it an ‘empty land’ belonging to nobody, Terra Nullius, and took the land they wanted. From 1910 to 1970, government policies tried to assimilate Aboriginal Australians. As part of this, 10 to 33 percent of Aboriginal children were taken from their families and placed in white-run boarding homes or in white foster homes. Members of these “Stolen Generations” were forbidden from speaking their native languages. Their names were often changed. [Source: Erin Blakemore, National Geographic, January 31, 2019]

Australian government policies in the 1900s that forcefully removed Aboriginal children from their parents, contributed to the reduction of the Aboriginal Australian population from more than 700,000 pre-European contact to a low of 74,000 in 1933. In the 1950s and 60s, the Australian government allowed Britain to test nuclear bombs at three sites in Australia — one off the Western Australian coast and two others in South Australia, at Emu Field and Maralinga — that were either on or near land occupied by Aboriginal families. [Source: CIA World Factbook, 2023; Ilsa Sharp, “CultureShock! A Survival Guide to Customs and Etiquette: Australia”, Marshall Cavendish, 2009]

Australia is the only country in the British Commonwealth that has never made a treaty with the indigenous people that lived there before the British arrived. Most First Nations people (Aboriginal Australians) did not have full citizenship or voting rights until 1965. Only in 1967 did Australians vote that federal laws would also apply to Aboriginal Australians. This meant that Aboriginal Australians and Torres Strait Islanders would be counted in Australia’s population. It also meant that Australia could make laws they had to follow.

Aboriginal activists would also like some reparations and limited autonomy for Aboriginals. Australia held its first Sorry Day in honor of Aboriginal children taken from their families in May 1998. The Australian parliament has acknowledged 200 years of injustice to Aboriginals and expressed regret for "the most blemished chapter" in the nation's history. However, some polls show that most white Australians feel it is not necessary to apologize to the Aboriginals. In 2000, Australian Prime Minister John Howard said he believed in reconciliation but refused to issue a formal apology for the mistreatment of Aboriginals in the past. He also set off a firestorm when he offered a personal apology in a speech before the Aboriginals Reconciliation Convention for the treatment of the Stolen Generation but did not make an apology on behalf of Australia as a whole. He was also jeered by the audience when he said that Australian history was not a history of "imperialism and exploitation and racism."

RELATED ARTICLES:

ABORIGINALS (FIRST NATION PEOPLE) OF AUSTRALIA: NAMES, DEMOGRAPHICS, LANGUAGES ioa.factsanddetails.com

EARLY MODERN HUMANS IN AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINALS AT THE TIME EUROPEAN COLONIZATION BEGAN ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL TASMANIANS: HISTORY, ABUSE, LIFESTYLE AND NEAR EXTINCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIA’S STOLEN GENERATIONS: VICTIMS, LAWS, RATIONALE, OUTRAGE ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL RELIGION: TRADITIONAL BELIEFS, DEMOGRAPHY AND DEATH ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL CUSTOMS, SOCIETY AND RITUALS ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL LIFE: WHERE THEY LIVE, WORK, DIET, HEALTH, ALCOHOL ioa.factsanddetails.com

TRADITIONAL ABORIGINAL LIFE: FOOD, HOMES, HUNTING ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIAN ART ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS IN QUEENSLAND: SOME GROUPS, CUSTOMS, LIFESTYLES ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIANS IN NORTH NORTHERN TERRITORY: SOME GROUPS, CUSTOMS, LIFESTYLE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS OF CENTRAL AUSTRALIA: SOME GROUPS, CUSTOMS, ART, LIFESTYLE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS IN WESTERN AUSTRALIA: SOME GROUPS, HISTORY, CUSTOMS, TRADITIONAL LIFE ioa.factsanddetails.com

Aboriginals and White Society in 20th Century

Ilsa Sharp wrote in “CultureShock! Australia”: By the beginning of the 20th century, the best an Aboriginal could expect from life was to be relegated to an Aboriginal reserve and get some sort of a job with the white man — on a farm, a cattle station or as a domestic servant. In some states, the Aboriginal was forbidden to consume alcohol, to marry or have sex across the colour line, or to carry a firearm. The ‘sex bar’ didn’t stop many of their white employers, however, systematically raping their female workers. The 1930s and well beyond, into the 1960s, saw a fully articulated policy of assimilation, with or without Aboriginal consent, for mixed bloods. [Source: Ilsa Sharp, “CultureShock! A Survival Guide to Customs and Etiquette: Australia”, Marshall Cavendish, 2009]

In the 20th century, the Aboriginals were looked on with pity by those of European descent. . Whites felt it was their duty to civilize them and Aboriginals were made protectorates of the state. Between the 1870s and 1960s, Aboriginals in Queensland were relocated from their homeland to government reserves and missions. Under a policy of assimilation, they were taught European ways and discouraged from practicing their customs or speaking their languages.

Describing Aboriginals and the new railroads in the 1910s in the Maamba Reserve in Western Australia, English writer Daisy Bates wrote, "They were all hypnotized by the metal snake...I could never persuade them to return to the places they had come from...When you see them walking naked out of the desert they appear like kings and queens, princes and princesses, but standing barefoot on the edge of the railroad track, dressed in stiff and stinking clothes, black hands held out to receive charity from white hands, then they are nothing more than derelicts, rubbish, that will soon be pushed to one side and removed."

Aboriginals, Whites, Laws and Land

In the early 1900s, legislation was passed to "protect and segregate Aboriginals”. The new laws restricted the rights of Aboriginals to own land, seek employment and live where they wanted. Some laws even gave the state the right to take Aboriginal children away from their parents.

Under the doctrine of "terra nullius," or empty land, white people took title to land because in the eyes of early white settlers Aboriginals were too primitive to have any claim on land and white Australians could claim land because it was presumed it didn't belong to anyone.

Terra nullius, a British doctrine, was first used by Captain Cook. It meant that Europeans could take land from Aboriginals without signing any treaties or providing any compensation. The Aboriginals had little choice but to go along with it. Even so they didn't understand the European concept of land ownership.

Stolen Generations

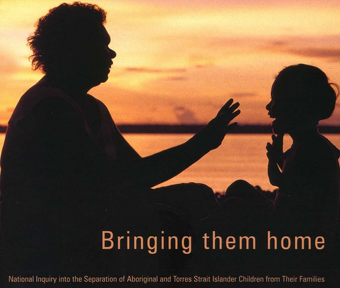

In a program that lasted from the 1910 to the 1970s about 100,000 Aboriginal children — 10 to 33 percent of all Aboriginal children — were taken from their parents by Australian authorities under state and federal laws to be raised in white-run institutions or foster homes with white parents. The practice continued 20 years after Australia joined a United Nations effort to abolish racial discrimination.

The term “Stolen Generations” is used today to describe the system and victims of it. The children were taken without a court order and made wards of the state from birth and Aboriginal parents were denied guardianship rights. Australia's Human Rights Commission later called the program genocidal because "forcibly transferring children" was done with "the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, the group."

Ilsa Sharp wrote in “CultureShock! Australia”: Out of a sort of twisted benevolence, the white authorities systematically removed Aboriginal children, particularly those of mixed blood, from their mothers ‘for their own good’, in an attempt to integrate them into white society and obliterate their aboriginality forever. Often, however, they were simply put into domestic servitude, akin to slavery. Descendants of Australia’s poor orphans, known as ‘The Stolen Generation’, are still searching for their families and discovering who they really are. Some experts have estimated that two thirds of all mixed blood children — thousands — were impacted by these policies, in the Northern Territory region alone, between 1912 and the 1960s.

In his speech opening Parliament in February 2007, Prime Minister Kevin Rudd assessed the overall picture: “...between 1910 and 1970, between 10 and 30 per cent of Indigenous children were forcibly taken from their mothers and fathers. ...as a result, up to 50,000 children were forcibly taken from their families.” [Source: Ilsa Sharp, “CultureShock! A Survival Guide to Customs and Etiquette: Australia”, Marshall Cavendish, 2009]

Robert Manne wrote in the Washington Post: No episode in the country's history is more ideologically sensitive than the story of the "stolen generations." In 1997 the publication of an official report into Aboriginal child removal precipitated a harrowing and as-yet-unresolved national debate. Liberal opinion was shocked by the revelation that a violation of such a profound and universal kind — the forcible separation of mothers and children — had occurred so widely and so recently. The right responded that if children were taken it was either because of maternal neglect or because half-castes were rejected by the "full-blood" tribes. The issue was clouded by preexisting arguments between supporters and opponents of Aboriginal land claims and the idea of reparations for past wrongs. Many people dismissed the report as propaganda. [Source: Robert Manne, Washington Post, February 2, 2003]

See Separate Article: AUSTRALIA’S STOLEN GENERATIONS: VICTIMS, LAWS, RATIONALE, OURAGE ioa.factsanddetails.com

Assimilation Policy and Treating Aboriginals as If They Were Wildlife

After World War II, the "assimilation" of Aboriginal people into European culture was a stated goal of the Australian government. As with other policies of the past, Aboriginals were only subjugated further. Under the terms of the policy, the government controlled where Aboriginal lived and even who they could marry. It is no surprise that the Aboriginal rights movement began around this time.

Before 1960 it was illegal for a white Australian to marry an Aboriginal. Until 1964 it was illegal for an Aboriginal to buy or drink alcohol, and anyone caught selling alcohol to one could be put in jail. Before 1967 Aboriginals existed only under the country’s flora and fauna laws. Into the 1980s, tea towels sold at souvenir stands used to have kangaroos, wombats and Aboriginals pictured as if they were all examples of Australian wildlife.Aborigine Jackie Huggins remembers the time when she was regarded as wildlife. Reuters reported: As a young girl, Huggins was not counted as part of the Australian population.Back then Aboriginals existed only under the country’s flora and fauna laws. [Source: Michael Perry, Reuters, May 24, 2007]

Aboriginal Linda Burney, a minister in the New South Wales government in the 2000s and 10 in 1967 when Aboriginals were given the right to vote told Reuters in the 1960s we were taught “my people were savages and the closest example to Stone Age man living today. I felt ashamed and embarrassed. I vividly recall wanting to turn into a piece of paper and slip quietly through the crack in the floor.”

Assimilation polices were not formally ended until 1972. Jim Crow-style discrimination laws were not outlawed until 1975. Aboriginal orphanages and reservations, many associated with the Stolen Generations were not closed down until the 1970s. Of all the states, Queensland and Western Australia have been the slowest to take action improving right for movers, with a generally poor record in race relations.

Aboriginals, Whites and Discrimination

Aboriginals used to and still do to some degree call themselves "blackfellas" and whites are referred to as "Gadia" or "whitefellas." Most white Australians have never had a conversation with an Aboriginal in their entire lives. Few Aboriginals live in white neighborhoods and they are much less assimilated into Australia society than many ethnic minorities such as Indians and Chinese. It is has been observed that white Australians have borrowed the Aboriginal customs of face painting (at rugby and football matches), go barefoot (in business class on commercial jets), cooking meat on the end of a sick and making bread in a campfire.

Aboriginal languages are not taught in schools although Maori is taught in New Zealand schools and many Australian students are learning Chinese, Vietnamese and Japanese. When writer Art Davidson asked an Australian woman next to him on a plane how people felt about the Aboriginals, she said: "Oh, some want to get rid of them. Some want them to disappear. And other like me just want to avoid them."

According to a report on race relations, Many white Australians feel that Aboriginals "have been brought up on welfare and come to expect it and they do nothing to help themselves, and that the take no responsibility for themselves." One white Australian told the Washington Post, "They would rather sit at home and drink. Why do they need to work? They get plenty of welfare." One Aboriginal who went to more than 35 businesses looking for a job and was rejected each time told the Washington Post, "The white people, they won't hire Aboriginal people. Racism is alive and well here."

Ilsa Sharp wrote in “CultureShock! Australia”: The scandal of Aboriginal deaths in police custody erupted into the public mind, with the 1991 publication of a Royal Commission enquiry into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody into at least 105 unexplained Aboriginal deaths in police and prison cells. In so many cases, what may have begun as a simple arrest for drunk and disorderly behaviour has ended with sudden death. The Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation and also the post of Aboriginal and Torres Straits Islander Social Justice Commissioner were established in response to the Royal Commission’s findings. There seems to have been little progress since 1991. Of all deaths in prison/custody, 20 percent were indigenous Australians in 2002; and whereas in 1991, 14 percent of the total prison population comprised indigenous Australians, by 2003 this figure had risen to 20 percent — very disproportionate in terms of Aboriginals accounting for 3.5 percent of the total population of Australia.[Source: Ilsa Sharp, “CultureShock! A Survival Guide to Customs and Etiquette: Australia”, Marshall Cavendish, 2009]

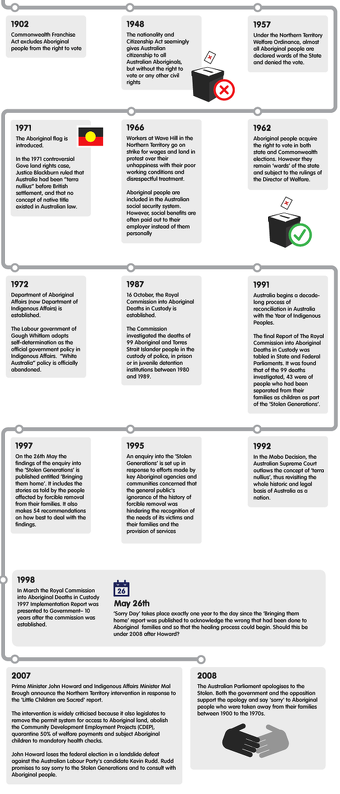

Timeline of Making Amends on Australian Aboriginal Injustices

1980s — According to Reuters: Academic Peter Read researches the history of forced separation policies dating back to the mid-1800s, and names those affected as the “Stolen Generations”. [Source: Reuters, February 13, 2008]

1995 — The “Bringing Them Home” national inquiry is set up into the separation of aboriginal children from their families. The report, tabled in the Australian parliament in 1997, found: 1) Between one in three and one in 10 indigenous children were forcibly removed from their families and communities between 1910 and 1970. 2) The children were at risk of physical and sexual abuse in institutions, church missions and foster homes. 3) The policies amounted to genocide under international law, and the laws were racially discriminatory. 4) It recommended a national apology, compensation for the Stolen Generations, and guarantees the policies would not be repeated.

Late 1990s — The state parliaments of New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia, Western Australia and Tasmania, as well as the Australian Capital Territory, apologize to the Stolen Generations in 1997. Queensland’s parliament apologized in 1999, and the Northern Territory parliament in 2001.

2000 — More than 250,000 people march across Sydney Harbour Bridge to support an apology. Tens of thousands of people attend similar marches across Australia. Conservative Prime Minister John Howard does not march. In 1999 he lead a parliamentary motion of “regret” for unspecified past injustices against Aboriginals, but refuses to apologize. He said an apology could leave the government liable for compensation claims, and current generations should not be responsible for past actions. In August 2000, a case involving two Aboriginals who sued the government for removing them from their families was thrown out court.

Late 2000s On February 13, 2008, the Australian Parliament apologizes for historic mistreatment of Aboriginals. The apology was delivered by Prime Minister Kevin Rudd, and is also referred to as the National Apology, or simply The Apology. Earlier, Prime Minister Howard said he believed in reconciliation but refused to issue a formal apology for the mistreatment of Aboriginals in the past. He also set off a firestorm when he offered a personal apology in a speech before the Aboriginals Reconciliation Convention for the treatment of the Stolen Generation but did not make an apology on behalf of Australia as a whole. He was also jeered by the audience when he said that Australian history was not a history of "imperialism and exploitation and racism."

In August 2007, a court made a landmark damages award of US$450,000 to Aborigine Bruce Trevorrow. He was taken from his mother without her consent when he was 13 months old and did not see her for a decade. In 2006, Tasmanian government set up million US$4.5 million fund to compensate Tasmanian Aboriginals who were removed from their families. In June, 2007, the conservative government sent police and troops to the Northern Territory to curb alcohol-related violence and sex abuse in Aboriginal communities, prompting indigenous fears that children could be taken away.

March 2022 — the government of the state of Victoria announced that Aboriginal Victorians from the Stolen Generations would receive A$100,000 as part of $A155 million reparations package. ABC reported that Aboriginal Victorians removed from their families in the state before 1977 were eligible to access the payments. Other states have also set up redress schemes. As of 2022, Western Australia and Queensland were the only jurisdictions which had not announced reparation schemes for the Stolen Generations. [Source: Richard Willingham, ABC, March 3, 2022]

Aboriginals Obtain Voting Rights and Citizenship in the 1960s

Aboriginal Australia obtained the right to vote in 1962. The Commonwealth Electoral Act 1962, approved on May 21, 1962, granted all First Nations people the option to enroll and vote in federal elections. Enrollment was not compulsory for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, unlike other Australians. Once enrolled, however, voting was compulsory.

Most First Nations people (Aboriginal Australians) did not have full citizenship until 1965. Only in 1967 did Australians vote that federal laws would also apply to Aboriginal Australians. This meant that Aboriginal Australians and Torres Strait Islanders would be counted in Australia’s population. It also meant that Australia could make laws they had to follow.

The 1967 referendum that gave Aboriginals full citizenship and set up of them to counted in censuses was voted on by white Australians. The Department of Aboriginal Affairs was set up by the federal government to make sure Aboriginals received the benefits given to other Australians and come up with policies to meet the special needs of Aboriginals.

Aborigine Jackie Huggins, head of Reconciliation Australia in the 2000s, told Reuters: “At 11 years of age I became a citizen of my own country, where my people had lived for 70,000 years. “Mum told me we would be counted in the census now, along with the sheep and cattle. I thought things would get really better now that we had the shackle of invisibility taken away,” she said. [Source: Michael Perry, Reuters, May 24, 2007]

Even so, the Aboriginals had a long way to go to become full citizens. A bark petition offered in 1962, demanding recognition of Aboriginal land rights of the Yolngu people of Arnhem land, was ignored. In the infamous Yirrkala Land Case 1971, a court ruled in the government favor, upholding “terra nulluius” and accepting the government's argument that Aboriginal people had no "meaningful economic, legal or political relationship with the land. Many Australians still object to Aboriginals being officially recognized by the government.

Aboriginal Land Rights Act

The Aboriginal Land Rights Act, often referred to as the Land Rights Act, was established in the Northern Territory in 1976. Regarded as the most comprehensive and powerful Aboriginal land rights legislation, it established three Aboriginal Land Councils, which were empowered to claim land on behalf of traditional Aboriginal owners.

The only catch was that only land that no one owned could be claimed. An Aboriginal claim to Ayers Rock an the Olgas was initially denied because the land for this rock formation lay within national park boundaries. Later, amendments were added that allowed Aboriginal to claim them with the understanding they would be leased to the government organization that runs the national parks. The 99-year lease is renegotiated every five years.

As of 2000, about half of Northern Territory had been claimed by Aboriginal through the Land Rights Act. The process to get the land was often lengthy because the Northern Territory government tried to block most of the claims. Once claimed, Aboriginal could negotiate the mining rights for the land.

The Pitjantjatjara Land Rights of 1981 and Maralinga Tjarutja Land Rights Act of 1984 were passed in South Australia. The are similar to the Aboriginal Land Rights Act established in the Northern Territory in 1976 except the did not necessarily guarantee Aboriginal the mining right to the land. Outside Northern Territory and South Australia, Aboriginal land rights are much weaker. In Queensland, less than 2 percent of the land can be claimed by Aboriginal. In New South Wales, Victoria and Tasmania, Aboriginal also can not claim much land.

In 1992, the Australian government first recognized the right of Aborigines to claim legal ownership of their ancestral lands—provided that they could show evidence of having an enduring connection with them. According to The New Yorker: Before proceeding to court, Aboriginal groups had to make their case before a Native Title Tribunal. Some Aboriginals were frustrated by their inability to articulate their arguments in courtroom English. There was also a logjam of cases contested by mining and farming interests. (If a land claim was validated in court, companies that operated on Aboriginal property would have to negotiate with the traditional owners and perhaps pay substantial fees.) [Source: Geraldine Brooks, The New Yorker, July 20, 2003]

As of the late 2000s around 11 to percent of Australia is held by the Aboriginal community in some form or another — often, under agreements merely allowing non-exclusive access to Aboriginal traditional owners, a very limited form of ‘ownership’. Land rights battles continue today, particularly when Aboriginal aspirations come into conflict with powerful mining and farming interests. [Source: Ilsa Sharp, “CultureShock! A Survival Guide to Customs and Etiquette: Australia”, Marshall Cavendish, 2009]

Important Mabo and Wik Aboriginal Land Rights Decisions

The notion of Terra nullius was rejected in 1992 in response to a suit filled by Torres Strait Islanders for possession of the Murray Islands in Queensland. An Australian High Court ruled that there was such a thing as native title, meaning that indigenous people could claim ancestral land. The Torres Strait ruling was heralded by the Labor government of Minister Paul Keating (1991-1996) but condemned by mining companies. Also known as the Mabo decision, named after Aboriginal land-rights negotiator Eddy Mabo, it opened up 5 percent of the land in Australia (including 30 percent of the land in the Cape York Peninsula) to claims.

In response to a claim brought by Wik and Thayoree Aboriginals, an Australian High Court ruled 4 to 3 in 1996 that Aboriginals who prove a traditional connection to their land could claim property rights and coexist on land leased by sheep and cattle ranchers (known as pastorialists in Australia) and mining companies. The ruling is known as the Wik Decision. The Wik claim pitted 188 traditional Aboriginal claimants against 19 defendants in battle over 10,000 square miles in the Cape York Peninsula, which includes one of the world's richest bauxite deposits.

Pastoral leases account for 40 percent of Australia's total land area and gold and base metal mining companies also use pastoral claims to obtain land. The intent of the Wik ruling, the court said, was to allow Aboriginals to hunt and conduct religious ceremonies on pastoral leased land but miners and ranchers worried the decision made pastoral lease vulnerable to Aboriginal claims for compensation on development. They lobbied the government to pass legislation limiting Aboriginal rights. Many of the rancher defendants in the Wik claim had nothing against the Aboriginals who brought the claim but did resent the lawyers and anthropologists who earned large sums of money off of it. The ranchers wanted an agreement that gave them title to the land in exchange for giving the Aboriginals access to it.

One Aboriginal group in the Northern territory surrendered rights to 2,500 acres of land in exchange for a kidney dialysis unit and an alcohol rehabilitation center.

In the late 1990s, Parliament rejected Howard;s proposals to scale back land rights won by Aboriginals. Howard defended his apology by saying that the present generation of Australians "should not be required to accept guilt and blame for past actions and policies over which they had no control." Howard also rejected a plan to give compensation payments to Aboriginals who taken from the their parents.

Attempts at Aboriginal Self-Government

The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC) (1990–2005) was the Australian Government body through which Aboriginal Australians and Torres Strait Islanders were formally involved in the processes of government affecting their lives. It was established under in 1990 under the Labour government of Prime Minister Bob Hawke (1983 to 1991). A number of Indigenous programs and organisations fell under the overall umbrella of ATSIC. The agency was dismantled in 2004 in the aftermath of corruption allegations and litigation involving its chairperson, Geoff Clark. [Source: Wikipedia]

According to Reuters: Billions of dollars have been spent trying to improve living standards, but many programmes have failed due to mismanagement, corruption and a lack of aboriginal support. In 2004, Prime Minister John Howard axed the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC), which ran aboriginal affairs, saying the “experiment” in black-elected representation had failed, arguing ATSIC was more interested in symbolic issues such as land rights than improving living standards. Many Aboriginals believe Howard has turned his back on reconciliation, preferring practical measures to improve black lives and rejecting spiritual issues. [Source: Michael Perry, Reuters, May 24, 2007]

Ilsa Sharp wrote in “CultureShock! Australia: The elaborate bureaucracy of organisations charged with promoting aboriginal interests that for a time flourished under the umbrella of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC) was was first formed in 1990 and hailed as a form of self-government for Aboriginals, charged with acting as the Aboriginal-run middle-man between government and Aboriginals, including the distribution of government funds. But in the 21st century, ATSIC became mired in controversy, particularly over its financial management, partly over the personal conduct of its senior executives. Conservative Premier John Howard’s Liberal government, among others, lost patience with the situation and legislated the organisation, with its 35 regional councils, out of existence. The delivery of services to Aboriginals would now be ‘mainstreamed’ into existing agencies serving the wider community, announced the government. While a new government-appointed National Indigenous Council was set up to advise the government, this was characterised by the government itself as a temporary measure pending the possible natural emergence of new bodies from within the Aboriginal community. [Source: Ilsa Sharp, “CultureShock! A Survival Guide to Customs and Etiquette: Australia”, Marshall Cavendish, 2009]

Critics, however, feel that the Aboriginals have lost the power to make decisions about their own lives, and they have also pointed to the government’s failure to replace ATSIC with any strong structure. On the other hand, some interesting alternative structures began to strengthen or emerge, particularly in the case of individually negotiated direct government-to-community ‘Shared Reponsibility Agreements’ that demanded a ‘two-way street’ for welfare payments, housing or other benefits given to Aboriginals; some of these have made it mandatory for Aboriginals to guarantee that their children would consistently attend school or even simply get their children to shower and wash their school uniforms regularly( both not at all the norm), in return for welfare. By 2008, almost 300 such agreements had been signed with different Aboriginal groups around the country.

2023 Referendum to Recognize Aboriginals in the Australia Constitution Rejected

In 2023, Australians overwhelmingly rejected a national referendum known as the “Voice” that would have recognized Aboriginal people in its constitution. It also aimed to create a group to advise Parliament on important issues. Although a majority of Indigenous voters said yes to the proposal, more than 60 percent of non-Aboriginal Australians voted no. Many Aboriginal Australians saw the referendum’s failure as a serious blow. They proclaimed a week of silence and reflection after it was voted down. Public servants in Queensland were offered five days' paid leave for psychological distress caused by the result. [Source: Erin Blakemore, National Geographic, January 31, 2019 updated 2025]

The advisory board proposed was to include Indigenous representatives from Australia’s six states and two territories. Each would have been voted in by local Indigenous community member-electors. Although the board would have “non-binding advice” on issues affecting Indigenous Australians, many saw it as a step in the right direction toward reconciliation. [Source: Phyllis Young, Native News Online, October 22, 2023]

The referendum, supported by Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese and Indigenous leaders, nevertheless faced opposition from both sides. Some Indigenous Australians and allies said it didn’t go far enough and argued they would be better served by a formal treaty. Victorian Yes campaigner Marcus Stewart told ABC News “The general Australian community couldn’t comprehend what exactly it was,” he says.Stewart says he thought No voters were not convinced that a Voice to Parliament was the right model to address systemic disadvantage. “They have not voted No because they’re racist. I categorically reject that. They have voted No because I think there’s a better pathway than constitutional enshrinement.” No campaigner, South Australian Liberal senator Kerrynne Liddle told ABC there was insufficient detail put to Australians. “People didn’t say No to reconciliation, they did not say No to improving the lives of Indigenous Australians.”

The No campaign, led by the conservative opposition, argued it would have created extra bureaucracy, embed “racial privilege” into the constitution, and turn Indigenous people into victims. Another opposition group, ‘progressive No’, said the Voice would be a “powerless” advisory board that did not go nearly far enough.

The debates "exposed racial fault lines" and prompted a "bitter culture war" in a country that has "long struggled to reckon with its colonial legacy", said The New York Times. The campaign "was like a sieve shaking out all of our ugly nuances", Ken Lechleitner Pangarte, an Aboriginal consultant, told The Washington Post. Speaking at an Aboriginal event 24 hours after the result, Aboriginal elder Vincent Forrester said voters "kicked us in the guts". He called on his audience to "show the world that Australia is a racist country". A "brutal" press campaign has been criticised. The result was not an example of "predictable, full-blown Aussie racism", argued novelist Thomas Keneally for The Guardian, because polls were initially "favourable to the idea". But then "grotesque" media stories and "fantastical propositions about what the powers of the [proposed Indigenous] body would be" turned the tide, he added.[Source: Chas Newkey-Burden, The Week UK, October 20, 2023]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Culture Shock! Australia, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated September 2025