Home | Category: Aboriginals

ARRERNTE

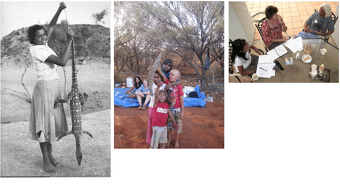

Arrernte ecological knowledge is acquired through practical experience but nowadays also partially shared in contexts distant from country: Left) Arrernte woman with a goanna, 1960; Middle) family and friends on a hunting trip in central Arrernte land, 2008; Right) Arrernte academics prepare during a focus meeting, 2008 researchgate

The Arrernte are also known as Aranda and Arunta. They are an Aboriginal Australian peoples of Central Australia, with their lands centered around Alice Springs (Mparntwe) in the Northern Territory. They are the traditional owners of the desert region they live in and are known for their rich cultural heritage, including their spiritual beliefs, languages, art, and totemic systems.

Arrernte and Aranda refer to a language group and a people. "Aranda" is a simplified, Australian English approximation of the traditional pronunciation of the name of Arrernte. Arrernte culture is expressed through ancient stories, rituals, and art, which are passed down through generations. Religious life was a significant aspect, with major gatherings held to conduct ceremonies and rituals. The concept of the Dreaming is central to Arrernte beliefs, representing a time of ancestral beings and the origin of life. While some Arrernte people still live in their traditional lands, others have moved to towns, major cities, or overseas. Efforts like "Aranda Tribe Ride for Pride" are underway to revitalize and teach Arrernte languages, which are considered vulnerable, and strengthen of community pride and the importance of passing on cultural knowledge,

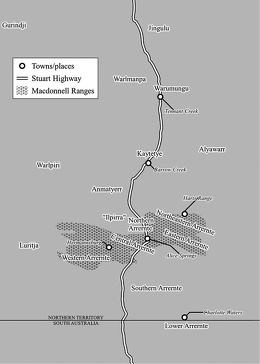

Arrerntic and Arandic groups have traditionally been distributed throughout the area of the Northern Territory, Queensland, and South Australia between 132° and 139° S and 20° and 27° E. Their territories were concentrated in the comparatively well-watered mountain areas of this desert region, though several groups—especially along the northern, eastern, and southern edges of the Arrernte-speaking area—also occupied vast sandhill country. [Source: John Morton, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

The estimated number of Arrernte people (and speakers of Arrernte languages) is around 3,000. The number of people with the Aranda surname is 2,605 individuals recorded in Australia's 2021 census data. The total population of Aranda speakers in precontact times was probably not over 3,000. The population fell very sharply after the arrival of white people, mainly as a result of the introduction of new diseases. At the present time the total population of Arrernte is rising, although the spatial and cultural distribution of the population has shifted dramatically. Major settlements at or near Hermannsburg, Alice Springs, and Santa Teresa account for the bulk of the Arrernte population. |~|

RELATED ARTICLES:

ABORIGINALS (FIRST NATION PEOPLE) OF AUSTRALIA: NAMES, DEMOGRAPHICS, LANGUAGES ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS OF CENTRAL AUSTRALIA: SOME GROUPS, CUSTOMS, ART, LIFESTYLE ioa.factsanddetails.com

WARLPIRI OF THE CENTRAL AUSTRALIAN DESERT: HISTORY, TRADITIONAL LIFE, CUSTOMS ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIANS IN NORTH NORTHERN TERRITORY: SOME GROUPS, CUSTOMS, LIFESTYLE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS IN QUEENSLAND: SOME GROUPS, CUSTOMS, LIFESTYLES ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS IN WESTERN AUSTRALIA: SOME GROUPS, HISTORY, CUSTOMS, TRADITIONAL LIFE ioa.factsanddetails.com

MARTU OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA: HISTORY, CUSTOMS, TRADITIONAL LIFE ioa.factsanddetails.com

NGAATJATJARRA PEOPLE OF WEST-CENTRAL AUSTRALIA: HISTORY, CUSTOMS, TRADITIONAL LIFE ioa.factsanddetails.com

PINTUPI OF AUSTRALIA’S WESTERN DESERT: HISTORY, CUSTOMS, TRADITIONAL LIFE ioa.factsanddetails.com

EARLY MODERN HUMANS IN AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

LIFE OF EARLIEST HUMANS IN AUSTRALIA: TOOLS, WEAPONS, ART, SETTLEMENTS ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINALS AT THE TIME EUROPEAN COLONIZATION BEGAN ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIA ABORIGINALS FROM 1900 TO PRESENT: DISCRIMINATION, ASSIMILATION, SOME RESTITUTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIA’S STOLEN GENERATIONS: VICTIMS, LAWS, RATIONALE, OUTRAGE ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL RELIGION: TRADITIONAL BELIEFS, DEMOGRAPHY AND DEATH ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL CUSTOMS, SOCIETY AND RITUALS ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL LIFE: WHERE THEY LIVE, WORK, DIET, HEALTH, ALCOHOL ioa.factsanddetails.com

TRADITIONAL ABORIGINAL LIFE: FOOD, HOMES, HUNTING ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL MEN AND WOMEN: GENDER, MARRIAGE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIAN SEX: PRACTICES, ATTITUDES, ADOLESCENCE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIAN ART ioa.factsanddetails.com

Arrernte Language and History

The ancestors of the Arrernte people spoke one or more of the many dialects within the Arrernte language group. In total, at least eleven dialects have been identified, each associated with a distinct cultural bloc inhabiting the desert regions of central Australia. The northernmost groups—including the Anmatjera, Kaititj, Iliaura (or Alyawarra), Jaroinga, and Andakerebina—are not typically referred to as Arrernte, despite being speakers of Arrernte dialects. The term Arrernte itself is a post-contact designation and is generally applied only to the following groups, some of which have since died out or lost their separate identities: Western Arrernte, Northern Arrernte, Eastern Arrernte, Central Arrernte, Upper Southern Arrernte (Pertame), and Lower Southern Arrernte (Alenyentharrpe). [Source: Wikipedia, John Morton, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

Today, several Arrernte languages are either extinct or nearing extinction, though some—particularly Eastern and Central Arrernte—remain widely spoken and are taught in schools. Among the Arandic dialects, Western Arrernte (spoken in the Hermannsburg/Alice Springs region) and Eastern Arrernte (spoken in the Alice Springs/Santa Teresa region) are the most prominent. The total number of Arrernte speakers is unlikely to exceed 3,000, with roughly half speaking Western Arrernte. Many speakers are proficient in multiple dialects, and a significant number are also fluent in additional languages, including various forms of English. Loanwords, especially from neighboring Western Desert and Warlpiri languages, are frequently adopted into Arrernte. Today, Arandic languages also exist in literary forms, supporting both publishing and bilingual education.

Aboriginal peoples have lived in central Australia for at least 50,000 years, though much of their early history remains unknown. When Europeans first entered Central Australia in the 1860s, the Arrernte lived as nomadic hunters and gatherers. From the 1870s onward, however, they gradually adopted a more settled—though still mobile—lifestyle on missions, pastoral stations, and government settlements. Relations among Arrernte groups, as well as between the Arrernte and their neighbors (primarily Western Desert peoples), ranged from cooperation through friendship, alliance, and intermarriage to periods of conflict and hostility.

Relations between the Arrernte and European settlers have shifted dramatically over time, encompassing periods of resistance through guerrilla warfare and cattle raiding, as well as phases of enforced or voluntary settlement and employment on missions and cattle stations. European attitudes and policies toward the Arrernte likewise ranged widely—from tolerance to prejudice, from neglect to paternalism, and from so-called protectionism to outright violence. Following World War II, with the rapid development of central Australia, the Arrernte were subject to the government’s policy of assimilation. More recently, they have been navigating the impacts of the policy of self-determination, which has brought increased involvement with Aboriginal-run bureaucracies and institutions.

Arrernte Religion

Arrernte cosmology is characterized by a distinction between sky and earth, with primary attention directed toward the earth. Numerous myths, or dreamings, recount how totemic ancestors created the universe and everything within it. Some of these accounts are sacred and restricted to certain initiated men or women, while others are more public—noncreationist stories often intended for children or general narration. Today, much of this mythology coexists with Christian narratives, hymns, and practices. The exchange and adaptation of religious knowledge across cultural groups has long been a feature of central Australia. Totemic ancestors are understood to be embodied within the land itself, their spiritual essences permeating the environment, which is also inhabited by malevolent spirit beings and ghosts. [Source: John Morton, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

Although there are no formal religious specialists, senior men within local groups often assume roles as ritual leaders or “bosses.” A wide range of ritual practices once existed, though only some remain actively performed. Traditionally, all adult men and women had rights to perform, sing, or oversee particular dreamings in ceremony. In contemporary times, some men also serve as Christian priests.

Death and Afterlife: Traditionally, death was followed by burial, a practice that continues today, typically accompanied by Christian rites. Upon death, one aspect of a person’s spirit may be annihilated, though it might first linger as a ghost. In some accounts, this spirit ascends to the sky—sometimes joining God, other times condemned to an evil place. Another aspect of the spirit, believed to originate from a totemic ancestor, returns to the earth and becomes part of the land. This essence may later be reincarnated in another human being, though such reincarnation is not regarded as personal survival or immortality.

Arrernte Marriage and Family

Arrernte marriages were traditionally arranged between families through a system of promised unions, though this practice has steadily declined in recent times. Today, individuals are just as likely to marry chosen partners, or “sweethearts,” as they are to enter unions with the prescribed kin categories. Ideally, a man’s marriage partner would be his mother’s mother’s brother’s daughter’s daughter, though alternative categories have always been permitted. Since European contact, the frequency of such “wrong” marriages has likely increased. In pre-contact times, bride-service was common, with a man often living with his parents-in-law while awaiting his promised wife’s maturity. Polygyny was permitted but not widespread, and it is now extremely rare. Divorce and the breaking of marriage promises appear to have always occurred. Intermarriage between dialect groups and between the Arrernte and other Aboriginal peoples is frequent, and unions between Aboriginal women and European men have also been relatively common. [Source: John Morton, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

A hearth group might include an older man, his wife, and their unmarried children, alongside other relatives such as parents, unmarried siblings, and sons-in-law fulfilling bride-service obligations. However, the size and composition of hearth groups have always been highly flexible, making it difficult to define a single “typical” form.

Arrernte children are generally indulged by their parents through infancy and childhood, only encountering stricter discipline at adolescence. Childrearing emphasizes the development of independence and autonomy, with deprivation and physical punishment usually disapproved of. Today, many Arrernte children attend school, some of which are bilingual and designed to meet their particular cultural needs.

Traditionally, the principal heritable property was land, along with the associated myths, ritual practices, and sacred objects that continue to serve as effective title deeds. Rights to land and ritual property are often the subject of careful negotiation and debate within the framework of ambilineal descent, though descent alone does not determine a person’s claims. Historically, the place of conception—and, less commonly, the place of birth—has also played a significant role in establishing such rights.

Traditional Arrernte Sexual Practices

The Arrernte practiced thelopoesis — preparation of the vulva. Thelopoesis often occurs by parental or tribal initiative. Female introcision (the enlargement of the vaginal opening by tearing or cutting the perineum) was practised among some of the aboriginal Australians (notably, Pitta-Patta, north-western Queensland) in order to facilitate the first experience of sexual intercourse. [Source: International Encyclopedia of Sexuality, edited by Robert T. Francoeur, Continuum International Publishing Group, 2004, online at the Kinsey Institute \^/]

Géza Róheim (1891-1953), a Hungarian psychoanalyst and anthropologist. interpreted the sexual meaning of Arrernte male initiation as follows: “It is quite evident that the mystery [of sex] revealed is the primal scene and that parental coitus is reenacted in each totemic ceremony. What are the principal differences between the original and the symbolic form? In the rite the end pleasure is not represented. The ritual offers another form of gratification to the son, that of interrupting the father in the sexual act. He is no longer excluded; he is initiated into the sexual mystery. This indeed is the “official”, that is, the conscious, meaning of the initiation rite, which introduces the sons into the hitherto forbidden realm of sex” (Eternal Ones of the Dream). The boy typically enters a ceremonial curriculum before puberty. In the (mostly) postpubertal stages this variably included circumcision, or subincision (mika). [Source: “Growing Up Sexually, Volume” I by D. F. Janssen, World Reference Atlas, 2004]

Róheim also stated that Australian mothers “lie on their sons in the [female on top] position and freely masturbate them” at night”. According to Róheim (1932), mother and child may lie in intercourse position and mothers practice infant genital play. The father, but not the mother, is used to mouth and “gently bite” the external genitalia of the child, as if eating them..

Arrernte Kin Groups and Land Tenure

In their hunting and gathering era, the Arrernte organized themselves into nomadic bands of bilateral kindred. The size and membership of these bands shifted over time, reflecting seasonal and social needs. Today, small settlements are often structured along similar kinship lines, with high mobility remaining a key feature. Larger settlements tend to be organized into neighborhoods, again emphasizing the centrality of extended family networks. Descent is cognatic ( tracing kinship and social affiliation through both male and female ancestors, rather than a single line) in some respects and ambilineal (a flexible system of kinship where an individual can choose to affiliate with a kin group through either their mother's line or their father's line in others, though there is a clear patrilineal bias. People generally regard themselves as belonging to a single territorially based cognatic group descended from one or more common ancestors, while also recognizing distinct lines of inheritance through both male and female ancestors—typically granting precedence to male descent. [Source: John Morton, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

The Arrernte themselves gave a name to a kinship system in which marriage is prescribed with a classificatory mother’s mother’s brother’s daughter’s daughter. At the time of European contact, some groups used a subsection system of eight marriage classes, while most followed the simpler section, or Kariera, system of four classes. Today, the subsection system is predominant among Arrernte groups. Moieties are acknowledged, though they are not given explicit names.

Individuals hold rights in land through all four grandparents and may also acquire rights through other avenues. Strong emphasis is placed on affiliation with the country of one’s paternal grandfather, though ties to the maternal grandfather’s country are also highly significant. Ultimately, land tenure is governed by ritual property, which serves as the basis of ownership and is distributed within a complex framework of political negotiation. In pre-contact times, local bands moved across the territories of wider alliance networks, maintaining relative economic self-sufficiency. These networks continue to exist, though the ability of Arrernte people to exercise full control over their lands has been severely constrained by European settlement. Today, most Arrernte territory is occupied by non-Aboriginal pastoralists, with only a small proportion legally recognized as owned and managed by Arrernte groups under Australian law.

Traditional Arrernte Life and Economic Activity

Although the Arrernte used to be nomadic hunters and gatherers, they had very clear notions of homelands. Within their territories, people followed well-established circuits during the seasonal round, establishing camps at named, well-watered places closely tied to mythological beings. The size of these camps varied widely: at times they consisted of a single extended family, while on other occasions they might host up to 200 people gathered for extended ceremonies. Life was largely lived in the open air, though temporary shelters and windbreaks were regularly built for protection from sun, wind, and rain. After European contact, similar shelters continued to be used on missions and pastoral stations, though often constructed from new materials such as tarpaulin or corrugated iron. More recently, houses of cement or brick with electricity and running water have become common in large settlements like Alice Springs, Hermannsburg, and Santa Teresa, as well as in outstations—small family-based communities established at sites of personal and mythological significance. [Source: John Morton, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

In traditional subsistence life, adult men hunted large game, while women and children, sometimes with men, hunted smaller animals and gathered fruits and vegetables. Women were the primary caregivers for children until adolescence, with men taking a strong role in the training of boys as they matured. Today, women often shoulder most domestic responsibilities, while men typically seek employment on pastoral stations or similar work. Many Arrernte who have received formal education now work in administrative or professional roles, and some are beginning to question the traditional ideology of sexual division of labor.

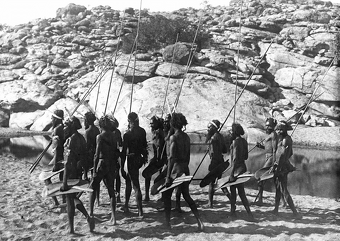

The traditional Arrernte toolkit was simple, consisting mainly of spears, spear-throwers, carrying trays, grinding stones, and digging sticks. Equipment for hunting and gathering was made by both men and women, without specialization. Large game included red kangaroos, euros (wallaroos), and emus; smaller game comprised marsupials, reptiles, and birds. Insects, fruits, vegetables, and grass seeds (the latter ground into flour for bread) were also important resources. Dingoes were sometimes domesticated and used as hunting companions. With the spread of European settlement, traditional hunting and gathering grounds were restricted, and the Arrernte became increasingly dependent on Western foodstuffs such as flour, sugar, and tea. Today, only limited hunting and gathering continues, with most food coming from supermarkets and local stores. Government social security payments and community development programs now play a major role in the local economy.

Trade has long been integral to Arrernte social life, as kinship ties involve continual exchanges of gifts and services. In pre-contact times, long-distance trade networks extended well beyond Arrernte territory for prized items such as ochre and pituri (native tobacco). In contemporary contexts, Arrernte people produce arts and crafts for both local use and the broader national tourism and art markets.

Arrernte Rituals, Art and Medicine

Men and women traditionally maintained distinct ritual spheres, a pattern that continues to some extent today. One historically significant ceremony—now less prominent—is the “increase ritual,” intended to ensure the fertility of local areas linked to specific totemic beings. Initiation ceremonies once included circumcision and subincision (slitting of the ventral surface) for boys and introcision (ritual defloration) for girls. Male initiation remains a central practice, while a third initiation rite, the inkgura festival, formerly brought clans together for several months whenever local resources could support a large gathering. [Source: John Morton, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

Artistic expression, largely though not exclusively tied to ritual contexts, encompasses body decoration, ground paintings, carved sacred boards, singing and chanting, dramatic performance, and storytelling. Common materials include feathers and down, pigments in red, yellow, black, and white, clap sticks, and small drone pipes. In the 1930s, many Western Arrernte artists successfully adopted watercolor painting, a tradition that continues today. Contemporary cultural interests extend beyond ritual: many Arrernte enjoy country music and action films, with guitar playing widespread and video production widely practiced.

The Arrernte carve sacred emblems called “tjurungas”. In the dreamtime each “tjurngas” was associated with a particular totemic ancestor and its spirit lived within it. When the spirit entered a women it was reincarnated as a child. Each person has his or her own “tjurngas”.

Traditional healing, performed by both men and women, draws primarily on shamanic practices, though a wide range of locally known medicines are also commonly used. Today, these healing traditions operate alongside Western medical systems. Most Arrernte women now give birth in hospitals, though traditional knowledge remains an important complement to biomedical care.

Arrernte Social and Political Organization

The primary bases of social differentiation among the Arrernte are sex and age. Beyond this, there is little specialization, though individuals with notable skills—such as traditional healing—may be granted higher prestige. Social life is marked by a strong ethic of egalitarianism, emphasizing individual autonomy within the limits of sex and age. While some kindred groups may expand in influence at the expense of others, the overall system remains relatively balanced. In broader contexts, racial and ethnic differences can also shape patterns of social organization. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

Politically, the Arrernte have been and remain largely autonomous, with authority exercised by elder men and, to a lesser though still significant extent, elder women. Such authority is closely tied to land. Territories are defined primarily through male descent, though rights may also be inherited through women. Elders exercise jurisdiction over ritual property associated with places in which they hold rights, as well as over younger relatives responsible for its care. Male initiation has long served as a key disciplinary institution, through which senior men exert authority over younger men. It also provides the means by which juniors eventually gain recognition as respected elders. Overall, political organization is inseparable from kinship and marriage structures, with territorial or dialect groups (often glossed as “tribes”) corresponding closely to local alliance networks. Today, this traditional system overlaps with local and federal structures of government in Australia.

The process of learning proper behavior unfolds over a lifetime, rooted in kinship obligations. Early childhood emphasizes generosity and compassion, fostering a sense of shared family identity. As individuals mature, they come to recognize that certain relationships require respect or avoidance, and that differing responsibilities apply in different contexts. Violations of law—often concerning ritual property, marriage arrangements, or access to women—may be resolved through mobility and asylum, though punishments have historically included violent sanctions such as spearing, sexual assault, or even death.

Conflict most often arises over issues of sexual relations, ritual property, land, or the distribution of locally generated wealth. Such disputes may manifest in sorcery accusations, violent feuding, or retaliatory “payback” killings. In many regions, especially where populations are dense, the frequency of conflict has increased, partly due to the forced cohabitation of different tribal groups and partly through the introduction and availability of alcohol.

Alice Springs

Many Arrernte live in the Alice Springs area. Alice Springs is a town of 30,000 pretty much smack dab in the middle of the Australian outback, seemingly light years away from any where else. Known locally as Alice, it is tourist town, home to a fairly large Aboriginal population and is a stepping stone to Ayers Rock and the Olgas. The people of Alice are hospitable and friendly. Those not in the tourist business usually make their living as part of the support mechanism that keeps the huge outback cattle ranches in the area going. Half the local a people are Aboriginals. They belong mostly to the Arremte group. The have inhabited the area, which they call Mpartntwe, for centuries. The major dreamtime figures are Yeperenyee, Ntyarlke and the Utnerrengatyne caterpillars.

Alice Springs is remarkable clean considering it dusty location. It has many shops and restaurants and many of the buildings are decorated with murals. The main drawback of the town is the heat, which can reach 46̊C (115̊F) in January in the summer. The Todd River runs through town and looks like a road. It is said that if you see it three times with water in it you can consider yourself a local. After flying, driving or training across hundreds of kilometers (miles) of red, empty desert to get there the first question many travelers ask is why is it here? Answer: Alice Springs developed as a market town for ranchers. The foothills of the MacDonnel Range receive enough rain to support grazing. In 1872 a telegraph station on the Adelaide to Darwin line was set up there because it was the only place within several hundred kilometers (miles) in all directions with a descent water supply. When this telegraph line was completed messages that once took three months to get from Adelaide to London took only seven hours.

Still not many people lived in Alice after that. In the 1920s only about a 100 people lived here. At that time the town was known as Stuart. In 1933, it became known as Alice Springs, the name of small spring that feeds a water hole used today for swimming. It was the destruction of Darwin during World War II that really put Alice Springs on the map. Northern Territorial Headquarters, which had been in Darwin, was moved to Alice and a 1,535 kilometers (954 mile) road or "bitumen" was built linking the two cities. It was considered a safe move because who would ever think of launching an attack on a city in Australian outback. In recent years Alice Springs has had issues with alcohol abuse and crime.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Culture Shock! Australia, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated September 2025