Home | Category: Aboriginals

WARLPIRI

Young Warlpiri men, from Aboriginal Bibles

The Warlpiri are an Australian Aboriginal group defined by their Warlpiri language. although some don’t speak it. There are 5,000–6,000 Warlpiri, living mostly in a few towns and settlements scattered through their traditional land in the Northern Territory, north and west of Alice Springs (Mparntwe). The Warlpiri are also known as the Yapa, Ilpirra, Wailpiri, Walbiri, Walpiri, Elpira, Ilpara and Wailbri. Walpiri.[Source: Wikipedia; Nicolas Peterson, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

Warlpiri country lies in central Australia, with its center about 180 kilometers (115 miles) northwest of Alice Springs. Traditionally the Warlpiri-speaking people occupied the Tanami Desert in a territory estimated to cover 140,000 square kilometers (53,000 square miles). Today many Warlpiri people live in Alice Springs, Tennant Creek, Katherine, and the smaller towns of Central Australia. Their largest communities are at Lajamanu, Nyirripi, Yuendumu, Alekarenge and Wirlyajarrayi/Willowra (an Aboriginally-owned cattle station). Others can be found scattered across the top of northern Australia and the Kimberly region.

Prior to colonization, it is estimated that there were around 1,200 Warlpiri speakers. By 1976, this number had increased to an estimated 2,700, perhaps somewhat generously. However, it can confidently be assumed that there are now more than 3,000 speakers. All of these people have Warlpiri as their first language and English as their second, third, or fourth language.

Warlpiri belongs to the Pama–Nyungan language family, which includes languages spoken in Cape York and the southern three-quarters of the continent. As with all Australian languages, the genetic relationship with languages outside the continent has been lost. Due to the tradition of widows observing a one- to two-year speech taboo after the death of a husband, Warlpiri women have developed a highly elaborate sign language that is still used by older individuals.

RELATED ARTICLES:

ABORIGINALS (FIRST NATION PEOPLE) OF AUSTRALIA: NAMES, DEMOGRAPHICS, LANGUAGES ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS OF CENTRAL AUSTRALIA: SOME GROUPS, CUSTOMS, ART, LIFESTYLE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ARRERNTE (ARANDA) PEOPLE: HISTORY, LANGUAGE, TRADITIONAL LIFE, CUSTOMS ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIANS IN NORTH NORTHERN TERRITORY: SOME GROUPS, CUSTOMS, LIFESTYLE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS IN QUEENSLAND: SOME GROUPS, CUSTOMS, LIFESTYLES ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS IN WESTERN AUSTRALIA: SOME GROUPS, HISTORY, CUSTOMS, TRADITIONAL LIFE ioa.factsanddetails.com

MARTU OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA: HISTORY, CUSTOMS, TRADITIONAL LIFE ioa.factsanddetails.com

NGAATJATJARRA PEOPLE OF WEST-CENTRAL AUSTRALIA: HISTORY, CUSTOMS, TRADITIONAL LIFE ioa.factsanddetails.com

PINTUPI OF AUSTRALIA’S WESTERN DESERT: HISTORY, CUSTOMS, TRADITIONAL LIFE ioa.factsanddetails.com

EARLY MODERN HUMANS IN AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

LIFE OF EARLIEST HUMANS IN AUSTRALIA: TOOLS, WEAPONS, ART, SETTLEMENTS ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINALS AT THE TIME EUROPEAN COLONIZATION BEGAN ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIA ABORIGINALS FROM 1900 TO PRESENT: DISCRIMINATION, ASSIMILATION, SOME RESTITUTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIA’S STOLEN GENERATIONS: VICTIMS, LAWS, RATIONALE, OUTRAGE ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL RELIGION: TRADITIONAL BELIEFS, DEMOGRAPHY AND DEATH ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL CUSTOMS, SOCIETY AND RITUALS ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL LIFE: WHERE THEY LIVE, WORK, DIET, HEALTH, ALCOHOL ioa.factsanddetails.com

TRADITIONAL ABORIGINAL LIFE: FOOD, HOMES, HUNTING ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL MEN AND WOMEN: GENDER, MARRIAGE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIAN SEX: PRACTICES, ATTITUDES, ADOLESCENCE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIAN ART ioa.factsanddetails.com

Warlpiri History

The oldest archeological site on Warlpiri land is likely the rock shelter at Purijarra, which contains evidence of human occupation dating back 38,000 years. Purijarra is located 300 kilometers west of Alice Springs in the Tanami Desert, which is a Warlpiri territory. Purijarra The site contains stone tools dated to 38,000 years ago — the earliest known evidence of human presence in central Australia. [Source: Google AI]

Warlpiri land From Sage Journals

European explorers began traversing Warlpiri country from 1862, but sustained contact came later with the expansion of the pastoral industry in the Victoria River District during the 1880s and the gold rush in the Halls Creek region around the same time. Short-lived gold rushes in the Tanami Desert followed in 1910 and again in 1930. Both the pastoral and mining industries drew on Aboriginal labor—though gold mining only briefly—while also bringing conflict and displacement for the Warlpiri communities living closest to them. [Source: Nicolas Peterson, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

From a European perspective, Warlpiri traditional territory was relatively resource-poor and lay far from the main telegraph lines and highway infrastructure. As a result, the Warlpiri were less directly affected by these developments, and their culture remained comparatively intact and vibrant—unlike that of neighboring groups such as the Anmatyerre, Kaytetye, Warumungu, Warlmanpa, Mudbura, and Jingili. One consequence was that by the 1980s, as Anmatyerre numbers declined, the Warlpiri expanded into their lands. [Source: Wikipedia]

Starting in the 1920s, the establishment of pastoral settlements in the area northwest of Alice Springs began to directly impact the Warlpiri people. This resulted in the killing of a station hand at Coniston Station in 1928, among other things. This sparked major reprisal expeditions, during which police and station workers admitted to killing thirty-one people, though the actual number of victims was likely much higher. The violence that ensued scattered the Warlpiri, some of whom sought refuge at other cattle stations. In 1946, the government established the Yuendumu settlement and moved many Warlpiri there, ending the period when some Warlpiri lived completely independently in the bush. Today, with government assistance, several small groups have established outstations or homeland centers in areas of their traditional lands, leading to limited recolonization of remote desert regions supported by modern technology. |~|

Warlpiri Religion

Approximately 70 percent of the Warlpiri people are Christians according to the Joshua Project, a Christian organization so these figures may not necessarily align with the Australia census data. This high percentage of Christian affiliation is consistent with other Aboriginal groups in Australia, where Christianity is the dominant religion among Indigenous people. It is not clear how strong traditional Warlpiri animistic beliefs and what aspects of them are retained by Warlpiri

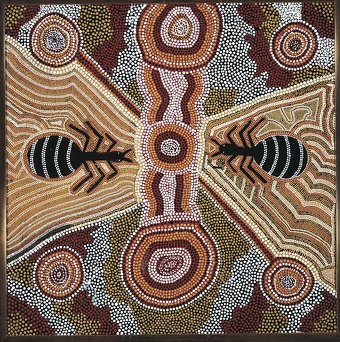

Yunkaranyi (Yurrampi) Jukurrpa (‘Honey Ant Dreaming’), 1986, by Louisa Lawson Napaljarri (1926-2001 )

Traditional Warlpiri religion is centered around the concept of Jukurrpa or "The Dreamings," a complex spiritual system involving totemic relationships and ceremonies. Jukurrpa refers to the period when the world was created, the landscape's features were formed, and the pre-European rules of conduct were established, all by the ancestral heroes. These beings were both human and nonhuman. They emerged from the ancestral spirit world underground and led a life much like traditional Warlpiri, only on a grander scale. They transformed the land surface into its present-day features through their activity. Sources of water emerged at each point where they engaged in creative acts, and they left behind life force in the form of spirit children at other places. These spirit children are responsible for new human and nonhuman life.

[Source: Nicolas Peterson, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

The ancestral heroes had designs on their bodies that carried the life force. These designs are reproduced in ceremonies today by men and women to renew the life force by recreating the founding dramas of their world. In addition to the ancestral beings, mildly malevolent spirits called gugu are often invoked to keep children close to adults at night and away from areas where men hold ceremonies. Mungamunga, female ancestral spirits, may appear to men or women in dreams with new songs, dances, or designs. Large or permanent bodies of water are thought to harbor rainbow serpents that can be offended if proper precautions are not taken. |~|

There is no distinct class of religious specialists among Warlpiri, as all adults participate actively in religious life. However, certain individuals are recognized as especially knowledgeable, often demonstrated through their command of an extensive repertoire of songs recounting the deeds of particular ancestral beings.|~|

Death and Afterlife Warlpiri believed that the individual personality dissolves after death, while the spirit returns to the ancestral spirit world. Of all aspects of Warlpiri life, mortuary practices and methods of body disposal have undergone some of the greatest change. Traditionally, the house of the deceased—if temporary—was vacated and destroyed, and burials were carried out on raised platforms, with the bones later collected and placed in termite mounds. Today, most people are interred in cemeteries, though in recent times some have again been buried in their home territories. |~|

Warlpiri Marriage and Family

In the past, all first marriages among the Warlpiri were arranged, often when the girl was very young or even before her birth. The average age difference between spouses at first marriage was around 21 years, with girls marrying at about age 10 to men in their thirties. Today, both the prevalence of arranged marriages and the age gap between spouses have declined sharply. Meggitt (1962) said that Warlbiri believed that having sex with prepubescent wives as helping to induce maturation. This idea was seen in many indigenous tribes. Among many Aboriginal groups female sexual maturity was attributed to the actions of men, either through intercourse, the performance of rites, or both. [Source: “Growing Up Sexually, Volume” I by D. F. Janssen, World Reference Atlas, 2004]

Traditionally, middle-aged men could expect to have two or three wives over the course of their lives, made possible by the delay in men’s first marriage, but this practice is now rapidly changing. Stable, enduring unions were considered the ideal, and separation or divorce was relatively rare. Yet, because of the significant age differences between husbands and wives, most women could expect to have several husbands over their lifetime, gaining greater choice in partners as they grew older. Preferred spouses in the past were classificatory second cousins, though today more marriages occur between first cousins, and occasionally between classificatory mother’s mother’s daughter’s sons. Intertribal marriages sometimes led to couples residing in the wife’s territory, though eventually children were generally brought back by the father to Warlpiri country. [Source: Nicolas Peterson, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

The domestic unit traditionally consisted of a man, his wife or wives, their unmarried children, and often an elderly dependent, usually a parent of one spouse. Widowed women members typically slept in a widows’ camp, where they were allowed to speak for two years, while boys aged 10 or older moved to a single men’s camp. |~|

Socialization of children occurred within the domestic unit, but mothers also spent much of their time with co-wives and close female relatives, who shared caregiving responsibilities. Children were generally indulged, with boys in particular enjoying considerable freedom. This freedom ended at marriage for girls and at initiation for boys, which involved seclusion and circumcision at around ages 11 to 13.

In terms of inheritance, material property to inherit was minimal. Upon death, a man’s senior maternal uncle supervised the distribution of his possessions: nephews’ belongings were divided among the uncle’s brothers, while nieces’ belongings went to his sisters. The same uncle also bore responsibility for arranging vengeance for his nephew’s or niece’s death.

Warlpiri Life and Economic Activity

Traditionally, shelter was mainly in the form of low windbreaks. During rainy periods, however, more substantial domed huts with spinifex thatch were used. Nowadays, most Warlpiri people live in towns ranging in size from 300 to 1,200 people, most of whom speak Warlpiri. Each town has a store where all daily nutritional and material needs are purchased, as well as a clinic, a primary school, a municipal office, a workshop, a church, and a police station. There are also a number of European-style houses.

Professional staff were almost exclusively non-Aboriginal and were assisted by Warlpiri coworkers but in recent years more Warlpiri have taken on more skilled jobs. White collar workers have traditionally lived in European houses alongside poorer Warlpiri, who live in various types of housing, ranging from "humpies" (tent-like structures made of corrugated iron sheets) to one- and two-room huts and more substantial housing. Access to water and electricity was often limited except for those in good housing, though the situation has slowly improved. [Source: Nicolas Peterson, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

Until settlement, the Warlpiri lived by hunting and gathering on a diet of roots, fruits, grass and tree seeds, lizards, and small marsupials, supplemented from time to time by large game in the form of kangaroos and emus. Traditionally, tasks have been organized along sex and age lines within the household, with women gathering vegetable foods and small game, and men hunting small and large game. |~|

Until the 1960s, many Warlpiri men worked as stockmen on nearby cattle stations, while a smaller number of women were employed as domestics in station homesteads. Those who remained in the settlements carried out community maintenance and odd jobs in exchange for rations and small amounts of cash. With the introduction of equal pay in the cattle industry in 1968, most Aboriginal workers were dismissed, leaving the majority of Warlpiri unemployed and reliant on transfer payments. Today, some are employed in schools, hospitals, or municipal offices, while others manage their own cattle station. In recent decades, the most significant commercial activity has become the production of paintings based on traditional designs, created for both local and, increasingly, international art markets.|~|

Traditional Warlpiri technology comprised a relatively small but versatile set of tools, including spears, spear throwers, digging sticks, wooden dishes, stone tools for cutting and maintenance, and hair string. The greatest diversity of objects, however, was religious in nature, created for both men’s and women’s public and secret ceremonies. These included sacred boards, poles, crosses, ceremonial hats, and ground paintings, often combined in elaborate arrangements with mounds, pits, and decorations made from plant down, feathers, and ochres. In the past, material culture circulated widely through systems of exchange. These transactions were primarily forms of gift exchange rather than matters of economic necessity. One of the most valued resources was red ochre from a mine at Mount Stanley, which was traded for items such as balls of hair string, spear shafts, and shields. From the Kimberley region, incised pearl shells and dentalia were brought into Warlpiri country. Such exchanges continue today, as does the reciprocal sharing of ceremonies with neighboring linguistic groups.|~|

Warlpiri Kinship and Land Tenure

The Warlpiri have an Arandic system of kinship with four terminological lines of descent but no named patrilineal (based on descent through the male line) or matrilineal (descent through the female line) descent groups. . There is not a simple division into brother and sister in the Arandic system. Instead, there are three terms, meaning, basically, 'elder brother', 'elder sister', 'younger sibling'. The Warlpiri also have patrilineal, matrilineal, and generational moieties (two-group divisions), semimoieties, and subsections. The subsection system divides the population into eight categories and distinguishes between female and male members of each category. While these categories are commonly used in everyday speech when talking to Europeans, they are not the persuasive organizers of activity they appear to be. Rather, they are a shorthand way of referring to matters organized by genealogy, land, religious interests, and other factors. [Source: Nicolas Peterson, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

The kinship terminology system of the Walpiri is of the bifurcate-merging type, recognizing sex differences among primary relatives but ignoring collaterality among most categories of kin. Bifurcate merging (also known as Iroquois kinship) is a kinship system that distinguishes between “same-sex” and “cross-sex” parental siblings, in addition to differentiating by gender and generation. The brothers of one’s father and the sisters of one’s mother are classified under the same kinship terms as Father and Mother. By contrast, a father’s sisters and a mother’s brothers are referred to with separate, non-parental terms, commonly translated into English as “Aunt” and “Uncle.” This distinction also applies to their children. The offspring of a father’s brother or a mother’s sister—known as parallel cousins—are treated as siblings and addressed with sibling kinship terms. By contrast, the children of a father’s sister or a mother’s brother—cross cousins—are not regarded as siblings, but are instead referred to with kinship terms typically translated into English as “cousin.” [Source: Wikipedia]

In regards to land tenure, rights to land and specific tracts of country (estates) may be acquired through one’s father or mother, but can also derive from the place of conception, the burial place of a parent, or through ceremonial ties to the journeys of an ancestral being who traveled widely. Although multiple pathways to land affiliation exist, Warlpiri ideology emphasizes patrilineal descent, giving primacy to rights inherited from the father. These patrilineal rights confer an absolute entitlement to use the everyday resources of the estate associated with the father’s lineage. Estates are not sharply bounded; rather, they tend to cluster around significant sites and are linked by ancestral or Dreaming tracks that connect important places.

Individuals connected to an estate through descent or other ties are expected to be consulted on matters concerning it. The weight given to their opinions depends on the type of rights they hold and, more significantly, on the depth of their ritual knowledge concerning that land. Patrilineal affiliation carries with it the expectation of being instructed in the body of religious knowledge tied to the estate. Maternal connections, however, are also highly valued: in middle age, people with such ties often act as custodians of their mother’s and maternal uncle’s heritage. They play an indispensable role in ceremonial organization, which cannot proceed without their participation. Since the passage of the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act in 1976 and the success of subsequent land claims, the Warlpiri now collectively hold most of their traditional lands in inalienable freehold and receive royalties from mining activities conducted on them.

Warlpiri Ceremonies, Dance, Art and Medicine

The Warlpiri have a rich religious life with a wide variety of ceremonies. They are known for their traditional dances, which have been featured at major events. Singing and dancing are used in Warlpiri religious ceremonies, boy initiations and childbirths, and to attack enemies, ensure fertility, cure sicknesses and to harness the powers of the Dreaming. There are songs commemorating the deeds of the heroic ancestors, which can be hundreds of lines long and match up with important Walkabout places. [Source: Wikipedia +]

Secular purlapa ceremonies are based on songs and dances received in dreams from ancestral spirits and subsequently developed into public performances. Other major ceremonial forms include male initiation rites; women’s yawulyu and men’s panpa ceremonies, which are separately performed rituals associated with paternal ancestral Dreamings; community-based ceremonies for conflict resolution and celebration of the winter solstice; large religious festivals; and magical or sorcery rites, usually carried out by individuals or small groups for immediate personal purposes. Settlement life has eased many of the logistical difficulties that once constrained ceremonial activity, resulting in a flourishing of ritual practice and a greatly expanded sphere of participation and exchange between communities. [Source: Wikipedia; Nicolas Peterson, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

Art is central to Warlpiri religious life. The designs given to the people by the ancestors are principal elements of religious property, important in substantiating rights to land and essential to the reproduction of people and nature. In the past, Warlpiri artwork was created on wood and sand. Then later, the artwork was made on the body of Warlpiri people. There is also a tradition of religious sculpture that is dismantled immediately following the ceremony for which it was constructed.

Today art shown in galleries and and traditions and laws found in it are passed on to future generations of the Warlpiri people. Many Indigenous artists, particularly in the Papunya Tula organization, are of Warlpiri descent. Warnayaka Art, in Lajamanu, Northern Territory, is owned by the artists, who create works across a range of traditional and contemporary art media. A small gallery displays the art, and some of the artists have been finalists in the national Aboriginal art contests.

A number of older people, almost all of whom are men, are thought to have healing powers and are called upon to treat the sick, especially when the major problem is internal and has no obvious immediate cause. A wide range of herbal medicines is known to people throughout the community and still used from time to time. |~|

Warlpiri Social and Political Organizations

Minor dialect variations among northern, southern, and eastern Warlpiri reflect loose regional kin networks, sometimes described as “communities,” but they have no corporate, political or territorial significance. As in the past, Warlpiri social life is organized around an economy of knowledge, where respect and authority are conferred on middle-aged and older men and women. [Source: Wikipedia; Nicolas Peterson, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

There are no institutionalized leadership roles or permanent community-wide political structures. Senior members of a patriline hold significant authority in religious matters, while in contemporary settlements town council chairmen and councillors may temporarily wield influence by controlling resources and funds. Such influence, however, tends to be short-lived, as it is eventually countered by strong egalitarian pressures.

Social control traditionally has been exercised informally, through public opinion, fear of sorcery, and the threat of supernatural sanctions for violating religious taboos. Older siblings may exercise some authority over younger siblings. In modern contexts, however, the absence of broad-based political structures poses challenges in addressing issues such as alcohol and vandalism, which are now usually handled by non-Aboriginal police.

In the past, conflict most often stemmed from disputes over deaths (almost always attributed to sorcery), women, or breaches of ritual rights. Traditional mechanisms for resolving such disputes included formalized duels and dispute-settlement ceremonies, while in some cases deaths were avenged by small groups of close kin pursuing the killer. Today, the availability of alcohol has aggravated conflicts, often undermining the effectiveness of traditional procedures.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Culture Shock! Australia, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated October 2025