Home | Category: Aboriginals

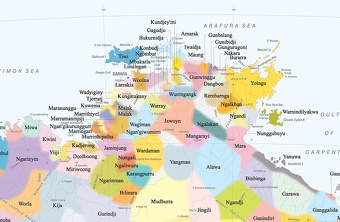

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIANS IN THE NORTHERN TERRITORY

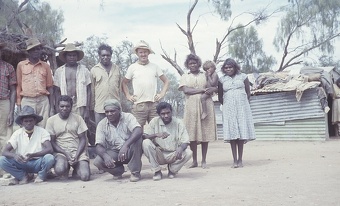

People attached to the PWD [Northern Territory Public Works Department in Alice Springs in the late 1950s

Aboriginal Australians made up 30.8 percent of the Northern Territory's population in the 2021 Census, the highest proportion of any Australian state or territory. This represented approximately 76,487 people, the majority of them resided in remote and very remote areas. Many live in Arnhem Land and around Alice Springs. Some live around Ayer's Rock.

Aboriginal Australians made up approximately 30.3 percent of the Northern Territory's total population, in 2006, 22.7 percent in 1991, and 22 percent in 1986 according to censuses taken those years. The increase in percentages from the 1990s to the 2000s was attributed to higher fertility rates, lower mortality, and improved census counting.

The Northern Territory is home to many Aboriginal groups, including the Warlpiri, Yolngu, Arrernte, Anindilyakwa, and Pitjantjatjara. Other groups include the Larrakia (traditional owners of Darwin) and numerous others across the territory, often grouped by language or geographical region, such as those in Arnhem Land or the Central Desert.

The Yolngu are found in eastern Arnhem Land, an area known for its distinct cultural practices and languages. The Arrernte are based around Alice Springs in the central part of the Northern Territory and speak Arandic languages. The Warlpiri live further north of the Arrernte. Their language is one of the most widely spoken Aboriginal languages. The Pitjantjatjara reside in the arid central south, near Uluru (Ayers Rock). Larrakia are The traditional custodians of the Darwin region. Anindilyakwa are the Indigenous peoples of the Groote Eylandt and surrounding islands in the Gulf of Carpentaria.

Northern Territory is abbreviated as NT; known formally as the Northern Territory of Australia and informally as the Territory. Covering 1,347,791 square kilometers (520,385 square miles), it occupies a large hunk of central Australia and northern Australia and is the third-largest Australian federal division, after Western Australia and Queensland, and is the 11th-largest country subdivision in the world. Northern Australia occupies 20 percent of Australia but embraces only one percent of Australia's population. Most of the territory is comprised of outback desert and most the roads are unsealed tracks. It is the home of Darwin, Arnhem Land, Kakadu National Park, Alice Springs, Ayers Rock and the Olgas as well as vast red sand deserts, meteorite craters and mystifying canyons. The northern part is the territory is called the Top End.

RELATED ARTICLES:

ABORIGINALS (FIRST NATION PEOPLE) OF AUSTRALIA: NAMES, DEMOGRAPHICS, LANGUAGES ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL ART OF NORTHERN AUSTRALIA: ANCIENT ROCK ART AND BARK PAINTINGS ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS IN QUEENSLAND: SOME GROUPS, CUSTOMS, LIFESTYLES ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS OF CENTRAL AUSTRALIA: SOME GROUPS, CUSTOMS, ART, LIFESTYLE ioa.factsanddetails.com

EARLY MODERN HUMANS IN AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

LIFE OF EARLIEST HUMANS IN AUSTRALIA: TOOLS, WEAPONS, ART, SETTLEMENTS ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINALS AT THE TIME EUROPEAN COLONIZATION BEGAN ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIA ABORIGINALS FROM 1900 TO PRESENT: DISCRIMINATION, ASSIMILATION, SOME RESTITUTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIA’S STOLEN GENERATIONS: VICTIMS, LAWS, RATIONALE, OUTRAGE ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL RELIGION: TRADITIONAL BELIEFS, DEMOGRAPHY AND DEATH ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL CUSTOMS, SOCIETY AND RITUALS ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL LIFE: WHERE THEY LIVE, WORK, DIET, HEALTH, ALCOHOL ioa.factsanddetails.com

TRADITIONAL ABORIGINAL LIFE: FOOD, HOMES, HUNTING ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL MEN AND WOMEN: GENDER, MARRIAGE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIAN SEX: PRACTICES, ATTITUDES, ADOLESCENCE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIAN ART ioa.factsanddetails.com

Arnhem Land

Arnhem Land (east of Kakadu National Park in northern Northern Territory) is an Indiana-size chunk of land divided by a straight line from Kakadu National Park. White people have traditionally are not been allowed in without the permission of an Aboriginal. Approximately 12,000 of the 16,000 people living in Arnhem Land are Aboriginals, primarily Yolngu people, the traditional custodian of the land. Official population data from the 2021 East Arnhem Census shows a local Indigenous population of around 7,893 people, with about 7,820 of these being Aboriginal but it is believed some people have not been counted.

Although more Aboriginals live elsewhere Arnhen Land is the one place where many of them still live like their ancestors. Situated in north-eastern corner of Northern Territory, Arnhem Land covers about 97,000 square kilometers (37,000 square miles) and is often divided into East Arnhem (Land) and West Arnhem (Land). The region's main town and is Nhulunbuy, 600 kilometers (370 miles) east of Darwin, set up in the early 1970s as a mining town for bauxite. Other major population centres are Yirrkala (just outside Nhulunbuy), Gunbalanya (formerly Oenpelli), Ramingining, and Maningrida.

A large proportion of the Aboriginal population live on small outstations or homelands. As part of outstation movement which took place mostly in the early 1980s many Aboriginal groups moved to usually very small settlements on their traditional lands, often to escape the problems of the larger towns. These population groups have very little Western cultural influence, and Arnhem Land is arguably one of the last areas in Australia that could be seen as a completely separate country. Many of the region's leaders have called and continue to call for a treaty that would allow the Yolŋu people to operate under their own traditional laws.

Kakadu National Park

Kakadu National Park (125 miles east of Darwin) is a great place for viewing wildlife as well as Aboriginal rock art. Declared a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1981, it covers an area of 19,804 square kilometers (7,646 square miles) — and area that is about half the size of Switzerland — and embraces all of northern Australia's major habitats — coastal fringe, woodlands, plateaus, rain forests, hills, wetlands and waterways.

Kakadu National Park is located within the Alligator Rivers Region of the Northern Territory. It extends nearly 200 kilometers (124 miles) from north to south and over 100 kilometers (62 miles) from east to west. It is the second-largest national park in Australia, after the Munga-Thirri–Simpson Desert National Park. Most of the region is owned by the Aboriginal traditional owners, who have occupied the land for 50,000 — maybe 60,000 — years and, today, manage the park jointly with Parks Australia.

Kakadu is a word from the Gagadju Aboriginal language. There are several Aboriginal settlements in the park. Many of the rangers are Aboriginals. The Arnhem Land Escarpment dominates the eastern side portion of the park. The northern portion of the park is a vast wetland in the Wet and a flood plain in the Dry. The wetlands are fed by four major rivers: the Wildman, West Alligator, North Alligator and East Alligator.

Kakadu Aboriginal Art

Kakadu abuts against the Aboriginal homeland of Arnhem Land, which occupies a large chunk of land along north Australia coast. In the 1.6 billion-year-old sandstone escarpments that run through the park are thousands of rock-art sites, some of which contain paintings that are believed to be 35,000 years old. Some are paintings. Some are engravings. Others designs in wax.

The rock paintings are sacred to Aboriginals. Many of the ocher and white clay images in the paintings depict "dreamtime" figures, specific gods that are usually associated with the places in which the art is located and are believed places the god dwells or dwelled in.

Most of these sites are natural landmarks, like sandstone rock formation with a feature that recalls something about a dreamtime spirit. These sites are visited over and over through time by generations of Aboriginal who renew themselves spiritually and maintain their bond with their gods and nature with each visit. Many of the painting are not paintings at all, the Aboriginal believe, but are images that have been placed where they are by the gods.

Traditional Sexual Behavior and Marriage Customs in Arnhem Land

According to “Growing Up Sexually: In Arnhemland, there is the establishment of a brother-sister taboo at age seven. This gender awareness is outstanding in most tribes. A relative separation of the sexes occurs when boys join the (bachelor’s) camp (jiridji for some tribes), and girls joins the women’s camp. The age at which this occurs is variable, rising up to subincision age, which is predominantly postpubescent. [Source: “Growing Up Sexually, Volume” I by D. F. Janssen, World Reference Atlas, 2004]

Child betrothal and marriage is noted for Arnhemland, According to Webb (1944): “A child a year old will sometimes be betrothed to an old man, and it will be his duty to protect and feed her, and (unless she is stolen by some one else) when she is old enough she becomes his wife. In the case of a husband’s death his wife belongs to the oldest man in his family, who either takes her himself or gives her to some one else”

Rowley stated that “Female children are betrothed as soon as they were born”. Strehlow (1913) wrote: “Children are betrothed in infancy, usually at two or three years age...When the boy is ten or twelve years old, he is informed that he must wait for marriage until his beard has grown and shows its first grey hairs”. Strehlow has set out the method of betrothal of a boy to a girl-child among the western Loritja people, and states that it is somewhat later than with the Arrernte, say between four and ten years. Chewings (1936) said: My own observations lead me to believe that instead of the betrothal being arranged for the son it is more often arranged for the man himself.” Rose (1960) notes for the Groote Eylandt Aboriginals: “Girls are normally promised as wife to men 20 or 30 years their senior before birth”. However, she runs the risk of dying or being stolen by another man before puberty. Girls go to live with their husbands at age 8 to 10.

Yolngu of Arnhem Land

The Yolngu are a group of Aboriginal Australians that reside in northeastern Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory of Australia. Yolngu means "person" in the Yolŋu languages. In the past anthropologists used the terms Murngin, Wulamba, Yalnumata, Murrgin and Yulangor for the Yolngu. They were also known as Miwuyt and Yuulngu. Wulamba was a Cultural Bloc. All Yolngu clans are affiliated with either the Dhuwa (also spelt Dua) or the Yirritja moiety (divided social-ritual group). Prominent Dhuwa clans include the Rirratjiŋu and Gälpu clans of the Dangu people, while the Gumatj clan is the most prominent in the Yirritja moiety. [Source: Wikipedia]

Yolngu is the word for "Aboriginal human being" in all the dialects. Aboriginal people in the Yolngu-speaking area refer to themselves as yolngu (as well as identifying all Aboriginal Australians as yolngu). Within the Yolngu area are some twenty such language-named, land-owning groups. In addition to the names of Language groups, Yolngu people describe and name themselves in a number of other ways, including the location and features of the land they own or where they live (for example, "beach people" or "river people"). [Source: Nancy M. Williams, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

The population of Yolngu people is spread across the East Arnhem region. Some sources count 5,000 Yolngu in North-East Arnhem Land, and approximately 12,000 overall . The Aboriginal population within the Yolngu area was estimated at 3,500 in the 1999s. The main population centers are developing towns and settlements that were formerly Protestant missions. The Yolngu area is roughly triangular and is located between 11° and 15° S and 134° and 137° E. The northern and eastern "sides" are coastal and the third "side" runs inland southeast from Cape Stewart on the north to south of Rose River on the east. Northeastern Arnhem Land is monsoonal, with northwest winds bringing rain during the Wet from about December until April or May.

See Separate Article: YOLNGU OF ARNHEM LAND: HISTORY, LANGUAGE, TRADITIONAL LIFE, CUSTOMS ioa.factsanddetails.com

Murrinh-Patha (Murinbata)

The Murrinh-Patha, also known as the Murinbata, are an Aboriginal people of northwest Australia, primarily centered around the community of Wadeye in the Northern Territory. Their traditional lands stretch between the Moyle and Fitzmaurice Rivers in the Thamarrurr Region. Today, the group numbers around 2,500 people. The Murrinh-Patha language remains one of the most vibrant Aboriginal languages, actively spoken by younger generations. It is a polysynthetic language, notable for its complex structure, its use of only four vowels, and its extensive system of thirty-eight verb classes. Far from declining, the language has experienced a resurgence, particularly among youth, and continues to serve as a cornerstone of cultural identity. [Source: EBSCO Information Services]

Socially, the Murrinh-Patha are organized into seven patrilineal clans, with descent traced through the male line. Each clan is associated with a totem, including the honeybee, the sugar glider, three species of birds, a tree blossom, and the morning star. Marriage generally occurs between members of different clans, reinforcing inter-clan ties. Music and ceremony play a central role in Murrinh-Patha cultural life. Each individual belongs to a ceremonial “mob,” named after one of three major public song traditions: djanba, wurltjirri, and malgarrin. Though comparatively recent—emerging only in the 1930s—these ceremonial groups are key markers of cultural identity today. 1) Djanba songs are linked to the Kunyibinyi clan’s totemic symbols, particularly the honeybee, and are regarded by researchers as intentionally cryptic in meaning. 2) Wurltjirri songs are accompanied by the didgeridoo and feature refrains repeated by a chorus. Unusually, some of these songs are traditionally led by women, a rarity in Aboriginal music involving the didgeridoo. 3Malgarrin songs were largely composed in the 1930s by a Murrinh-Patha woman named Mulindjin, who said she was inspired by a vision of the Virgin Mary during the Aboriginal mythological era known as the Dreamtime. Consequently, many malgarrin songs carry strongly Christian themes. They are often performed with clapsticks, played by the male song-leader.

According to “Growing Up Sexually: Falkenberg and Falkenberg (1981) state that, although prohibited, immature uncircumcised boys from the Marinbata tribe, use prepubertal and neopubescent girls of their own clan after being turned down by older girls of other clans. They use secretions of a specific orchid (tjalamajin) applied to the penis as a lubricant; a modern substitute is soap. Precircumcision intercourse is discouraged by the adults males by the prospect of the induration of the preputial sinew, producing a more painful circumcision, and a blackening of the interior mucus, producing a stigma to be revealed at initiation. The boys, however, secure the others that this is untrue. Among the Warramunga the foreskin may be put in the burrow of a ground spider after circumcision...in which case it is supposed to cause the penis to grow”. [Source: “Growing Up Sexually, Volume” I by D. F. Janssen, World Reference Atlas, 2004]

Murrinh-Patha Religion and Karwadi Ceremony

Since the arrival of Christianity, many Murrinh-Patha have embraced Christian beliefs, often blending them with traditional practices. Traditionally, their cosmology traced human origins to a single ancestor known as Kunmanggur. Kunmanggur was first born as a rainbow-colored python. Seeing the land empty of people, he resolved to create humanity. Using a didgeridoo, he fashioned the first boy and girl. Transforming himself into human form, Kunmanggur raised the children, teaching them how to live in harmony with the land and with one another. When they were grown, he sent them out to populate the world. [Source: EBSCO Information Services]

Generations later, Kunmanggur married one of their descendants and fathered two daughters and a son, Tjinimin. Conflict arose when Tjinimin desired his sisters, an act Kunmanggur forbade. In anger, Tjinimin destroyed the sacred didgeridoo that had been used to shape humanity and attempted to kill his father. Overcome by guilt and fear, Tjinimin transformed into a bat, fleeing into the night. His cries, the Murrinh-Patha say, are still heard in the shrieks of bats, echoing his shame. Though attacked, Kunmanggur survived. He wandered among his people, striving to restore peace to humankind. At last, he died and returned to his original form, the great rainbow python, embodying both creation and renewal.

The Murrinh-Patha conducted a bullroarer initiation ceremony, known secretly as Karwadi, and publicly as the Punj. A bullroarer is a piece of wood attached to a string that produces a roaring sound when whirled. It represents ancestral spirits and ward off evil. W. E. H. Stanner analyzed the ceremony and wrote: The Karwadi ceremony may be described as a liturgical transaction, within a totemic idiom of symbolism, between men and a spiritual being on whom they conceive themselves to be dependent. [Source: Wikipedia

The Karwadi ceremony and everything that went along with it took from one to two months to complete and involved participants from both patrimoiety groups (kinship groups determined by a person’s father's male line of descent) and neighboring clans. It marked the final stage of initiation for young men who had already undergone circumcision but were still considered resistant to the discipline of full adulthood. The term Karwadi is a secret name for the Mother of All, also called the Old Woman, and the central focus of the ceremony lay in the revelation of her emblem, the ŋawuru (bullroarer).

Following consultation, the initiates—who participated voluntarily—were led to the ŋudanu (ceremonial ground), where the fully initiated men (kadu punj) encircled them and chanted a long refrain. As the sun set, the chant culminated in the exclamation of the Mother of All’s hidden name, invoked with the cry Karwadi yoi! Afterward, all returned to the main camp. During this period, the initiates were forbidden to speak with either patrikin or matrikin and were required to eat in seclusion, their needs attended by adult men.

With the first rising of the Morning Star, the initiates were once again brought to the ŋudanu. From that moment until the ceremony’s conclusion, they were neither addressed nor even seen by anyone outside the group of adult men supervising the rites. The singing resumed, punctuated by the antics of tjirmumuk, a form of ritualized horseplay between members of opposite moieties. These bouts included jostling, mock attempts to seize one another’s genitals, and the exchange of obscene remarks — behaviors normally considered unacceptable outside this ceremonial context.

Gaagudju Aboriginals

The Gaagudju, also known as the Gagudju and Kakadu, are an Aboriginal Australian people of the Northern Territory. They occupied parts of Kakadu National Park and their ancestors are believed have painted rock art there. There are four clans, being the Bunitj (Bunidj), the Djindibi (around Munmalarri), and two Mirarr clans. Three languages are spoken among the Mirarr or Mirrar clan: the majority speak Kundjeyhmi, while others speak Gaagudju and others another language. Gaagudju is a language spoken by a primary group known by that name, and a secondary group of contiguous peoples who used it as a second language until their languages died in the the 1930s when it became their first language. Few if any people speak these languages any more. [Source: Wikipedia]

Norman Tindale (1900-1993) estimated the Gaagudju once possessed land inland of the Van Diemen Gulf that covered 6,000 square kilometers (2,300 square miles) between the eastern and southern Alligator Rivers, and running southwards as far as the mountain country. They were resident at both Cannon Hill and Mount Basedow. The Cobourg cattle company took up a lease for hunting buffalo in the Alligator River area in 1876, and Aboriginal people became a major part of the workforce.

After the arrival of the feral buffalo hunter Paddy Cahill in their area (around Munmalarri) in the 1880s, they were employed by him to track, kill and harvest the meat of buffalo. For many decades this was the Gaagudja’s main work. There was a dramatic population collapse in that area from 1880 to 1920 due to introduced diseases and new colonial land use. After Cahill's death the Gaahudju shifted to the Alice and Mary River areas, to continue buffalo hunting, and gradually the former lands they occupied were taken over by the Kunwinjku, who moved in from the west.

Gaagudju Religion and Rituals

The main Gaagudju totem spirits were Marrawuti, the sea eagle, who carried off a person's soul when he or she died; Bjuway, the bowerbird, who maintained the initiation ceremonies; and Ginga, the crocodile, who got the lumps on his back when he was blistered in a fire.[Source: "The First Australians" by Stephen Breeden and Belinda Wright, National Geographic February 1988]

The rainbow snake, the symbol of the northeast monsoon, not coincidently was also the creator spirit who brought life and mades things grow. The yellowbelly water snake was the spirit of lighting. The file snake brought rain. Men can also could bring rain by imitating the sound of the a snake and he easiest way to do this was stay home and sleep. For the Aboriginals the sound of hissing snake and snoring are about the same. The Rainbow Serpent is an important dreamtime figure in the Kakadu, Arnhem Land area, She is a woman spirits who spends most of her time at rest in billibogs. When disturbed she can emerge and reek havoc, causing flood or earthquakes, There are even stories of her eating people.

During a traditional Gaagudju burial ceremony the body is first wrapped in bark paper and placed in a tree. After a year the bones are collected, painted with red ocher and placed ceremoniously into a cave. For the deceased's soul to find its way to heaven the formalities of the ceremony must be performed correctly. As of 1988 only one man knew how to perform the ceremony.

The complete Gaagudju initiation ceremony has not been performed since the 1950s. Part of the ritual that was still done in the 1980s is the making of hand paintings in cave near the image of Garrkine, the brown falcon, who taught people how to catch fish. These painting are made by an initiate who fills his mouth with paint and then spits it out all over his hand. The image created is the outline around his hand.

Gaagudju Lifestyle and Art

Malangager is a cave in Kakadu National Park that has been inhabited for more than 23,000 years by the Gaagudju. Up until about 1975 people lived there. A careful look through the cave reveals artifacts such as flint-spears heads, scrapers, animal bones, beer cans and used batteries. In the 1980s some Gaagudju elders still used stone tools. Knives, for example, were chipped off of blocks of quartzite. Elders used to use these rocks to pierce the septum in their noses. Some Gaagudju can stick a finger in one nostril and have it come out the other. [Source: "The First Australians" by Stephen Breeden and Belinda Wright, National Geographic February 1988]

Gaagudju knew know that stringrays were plump and ready to eat when a certain flowers blooms. They prefer their crocodile eggs hard boiled and still hunted for crocodile eggs in 1980s. The crocodile is viewed as the totem animal of central Arnhem Land.

The oldest Gaagudju paintings are at least 20,000 years old. In the 1980s they no loner made rock paintings. Instead the made bark paintings which were sold at galleries. In the Ubirr Gallery at Kakadu National Park there is a painting of white man. Describing the painting an Aboriginal elder said, "it is a man standing with his hands in his pockets, telling us what to do."

According to legend the Mimi spirits taught Aboriginals how to paint and hunt kangaroo. According to a Gaagudju elder the Mimis live in between rocks and are so thin they only paint on calm days because a strong wind could break their necks. Yirrkala in eastern Arnhem Land is known for bark paintings. The Yirrkala believed the first Aboriginals were born to a pair of sisters.

Tiwi People

The Tiwi people are the inhabitants and owners of Melville and Bathurst islands of north Australia. Also known as Bathurst Islanders and Melville Islanders, they number about 2,000 divided between the Bathhurst Island township Nguiu with 1,300 people and the two Melville Island townships of Parlingimpi and Milikapiti with 300 and 400, respectively. The word "Tiwi" means "people" in the Tiwi language.[Source: Wikipedia; Jane C. Goodale, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Tiwi society is organized around matrilineal descent, with marriage serving as a central institution in both social and cultural life. Art and music are integral to ceremonial expression, playing a vital role in spiritual practice and community identity. Traditionally, Tiwi beliefs reflect an animist worldview in which the natural and spiritual realms are closely intertwined. During the Stolen Generations period from the 1910s to the 1970s many Indigenous people were brought to the Tiwi Islands who were not of direct Tiwi descent.

The distinctive Tiwi language is distantly related to other Aboriginal languages but has no apparent link to the languages of Arnhem Land on the Australian mainland not so far to the south. Nearly everyone uses both Tiwi and English. However, elders lament the decline in Tiwi fluency among younger generations. In the past, fluency in Tiwi was an important marker of adulthood, allowing both men and women to fully participate in the significant ceremonial activity of composing and singing songs.

See Separate Article: TIWI PEOPLE OF NORTHERN AUSTRALIA: HISTORY, CUSTOMS, TRADITIONAL LIFE ioa.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Culture Shock! Australia, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated September 2025