Home | Category: Aboriginals / Arts, Culture, Media

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIAN ART TODAY

Eric Kjellgren wrote: After more than two centuries of Western settlement and expansion, Aboriginal peoples today represent only a small proportion of the population of the modern nation of Australia. However, despite the long and often tragic history of relations between Aboriginal and settler societies, the arts of Aboriginal Australia have endured. Although many earlier art forms, such as bark painting and the creation of ceremonial objects, continue, the early 1970s witnessed the emergence of Australia's burgeoning contemporary Aboriginal art movement. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

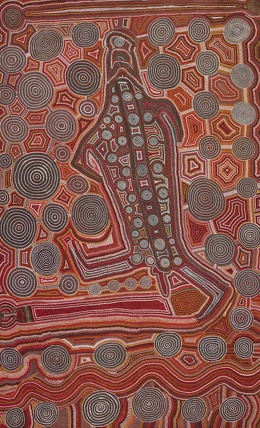

Beginning in the remote communities of the central desert, whose boldly colored acrylic canvases are at times called "dot" paintings because of their distinctive dotted backgrounds, the movement quickly spread to the Kimberley, Queensland, and other regions, where artists began to produce paintings in their own distinctive styles. In the major cities artists from urban Aboriginal communities also began to create works in a diversity of styles, employing the same broad range of artistic media as their non-Aboriginal counterparts.

Today, the arts of Aboriginal Australia are flourishing, and modern Aboriginal painting is increasingly gaining recognition on the world stage as an important movement in contemporary art. Almost all Aboriginal peoples today are Christian. However, in many areas they continue to practice aspects of their indigenous ceremonial traditions. Ilsa Sharp wrote in “CultureShock! Australia”: The success of Aboriginal art has already helped restore the Aboriginals’ pride in themselves and their culture, quite apart from bringing them income. But a contentious issue of today raises the question of ‘intellectual copyright’: whether or not white-community ‘borrowing’ and commercialisation of Aboriginal styles and themes constitute both — and exploitation. Aboriginal art promoters today have to take a lot more care with how they market the product and how much of the resulting income they remit to the originators, the Aboriginals themselves. [Source: Ilsa Sharp, “CultureShock! A Survival Guide to Customs and Etiquette: Australia”, Marshall Cavendish, 2009]

Aboriginal lawyer and writer Larissa Behrendt wrote in the Aboriginal Art Directory: It has been long understood that the genesis of art within Australian Aboriginal culture was vastly different to that in the Western tradition. The creativity of creating art was, for pre-invasion Aboriginal communities, solely part of the cultural practices that showed, connection to country and honoured ancestors. The end result was often discarded and destroyed, made in non-permanent mediums like sand and not kept for aesthetics or valued as property. The recognition of Aboriginal art as aesthetic, not mere artefact, has meant Europeans reconceptualising ethnographic objects into art. Aboriginal people were encouraged to put their fragile and non-lasting artwork into permanent forms – on canvas, board and bark (where it was not traditionally done) and with watercolours and acrylics. This mirrored the process of changing the mediums for Aboriginal artists – turning sand paintings into acrylic paintings, placing body paint onto canvas, the classification of functional pieces – baskets, boomerangs, shields – as sculpture. These new mediums were an extension of the traditional motifs, symbols and representations and remained fundamentally and intrinsically Indigenous. Aboriginal artists were producing and selling a whole new genre of art specially created to communicate with the outside world.

RELATED ARTICLES:

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIAN ART ioa.factsanddetails.com

VERY, VERY OLD AUSTRALIAN AND ABORIGINAL ROCK ART ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL PAINTINGS ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL ART FROM DIFFERENT REGIONS ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL ART OF NORTHERN AUSTRALIA: ANCIENT ROCK ART AND BARK PAINTINGS ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL ART FROM QUEENSLAND AND THE TORRES STRAIT ioa.factsanddetails.com

WELL-KNOWN ABORIGINAL ARTISTS: THEIR LIVES, WORKS AND IMPACTS ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS (FIRST NATION PEOPLE) OF AUSTRALIA: NAMES, DEMOGRAPHICS, LANGUAGES ioa.factsanddetails.com

EARLY MODERN HUMANS IN AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

LIFE OF EARLIEST HUMANS IN AUSTRALIA: TOOLS, WEAPONS, ART, SETTLEMENTS ioa.factsanddetails.com

PEOPLE WHO LIVED AUSTRALIA 20,000 TO 10,000 YEARS AGO ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

RITUAL LIFE AND MYTHS OF ANCIENT AUSTRALIANS ioa.factsanddetails.com

EARLY ABORIGINALS ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINALS AT THE TIME EUROPEAN COLONIZATION BEGAN ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIA ABORIGINALS FROM 1900 TO PRESENT: DISCRIMINATION, ASSIMILATION, SOME RESTITUTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIA’S STOLEN GENERATIONS: VICTIMS, LAWS, RATIONALE, OUTRAGE ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL RELIGION: TRADITIONAL BELIEFS, DEMOGRAPHY AND DEATH ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL CUSTOMS, SOCIETY AND RITUALS ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL LIFE: WHERE THEY LIVE, WORK, DIET, HEALTH, ALCOHOL ioa.factsanddetails.com

TRADITIONAL ABORIGINAL LIFE: FOOD, HOMES, HUNTING ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL MEN AND WOMEN: GENDER, MARRIAGE, SEX ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIAN SEX: PRACTICES, ATTITUDES, ADOLESCENCE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS IN QUEENSLAND: SOME GROUPS, CUSTOMS, LIFESTYLES ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIANS IN NORTH NORTHERN TERRITORY: SOME GROUPS, CUSTOMS, LIFESTYLE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS OF CENTRAL AUSTRALIA: SOME GROUPS, CUSTOMS, ART, LIFESTYLE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS IN WESTERN AUSTRALIA: SOME GROUPS, HISTORY, CUSTOMS, TRADITIONAL LIFE ioa.factsanddetails.com

Australian Aboriginal Art Revival in Papunya

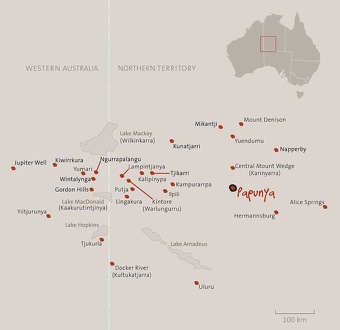

The revival of Australian Aboriginal art began in Papunya ("Honey Ant Place"), a small Aboriginal community 245 kilometers (150 miles) northwest of Alice Spring in the Northern Territory in arid Central Australia. In the 1970s, villages elders there became interested in an elementary school project to create a mural of traditional Aboriginal images and, for the first time, images that had been confined to rock and body painting were expressed in alternative medium. More murals followed and skilled artists moved from small boards to canvases and acrylics.

Today, Papunya Tula, registered as Papunya Tula Artists Pty Ltd, is an artist cooperative formed in 1972 in Papunya. It is owned and operated by Aboriginal people from the Western Desert region. The group is known for its innovative contributions to the Western Desert Art Movement, popularly referred to as "dot painting." The cooperative is credited with bringing contemporary Aboriginal art to the attention of the world. Its artists have inspired many other Australian Aboriginal artists and styles. The company is based in Alice Springs, and its artists are drawn from a large area extending into Western Australia, 700 kilometers (430 miles) west of Alice Springs. [Source: Wikipedia]

Hetti Perkins and Hannah Fink wrote through their paintings, , the artists "trace the genealogies of their ancestral inheritance". And comment that "Through the paintings of the Papunya Tula Artists we experience the anguish of exile and the liberation of exodus. ... In refiguring the Australian landscape, the artists express what has always been known to them. And in revealing this vision to an outside audience, Papunya Tula artists have reclaimed the interior of the Australian continent as Aboriginal land. If exile is the dream of home, the physical longing for homelands expressed in the early paintings has now been answered".

In 2007, a single painting by Papunya Tula artist Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri set a record at auction for price commanded for Aboriginal art. It was sold for A$2.4 million, more than twice as much as the previous record-holder. It was bought by the National Gallery of Australia, which considered it the artist's greatest work. The painting, Warlugulong, was created in 1977 and depicts the story of an ancestral being called Lungkata, along with other "dreamings" (stories).

On aspect of the art revival unleashed in Papunya has been the appearance of Secret designs, which were previously restricted to a ritual context, in the marketplace, where they are visible to outsiders and Aboriginal women. In response, all detailed depictions of human figures, fully decorated tjurungas (bullroarers), and ceremonial paraphernalia were removed or modified. These designs and their "inside" meanings were not to be written down or "traded." Any violation of this rule would break the immutable plan of descent, severing the link between initiated men and their totemic ancestors through their fathers and grandfathers.

Origin of Papunya Aboriginal Art

In the late 1960s, the Australian Government moved several different groups living in the Western Desert region to Papunya to remove them from cattle lands and assimilate them into western culture. These displaced groups were primarily Pintupi, Luritja, Walpiri, Arrernte, and Anmatyerre peoples. In 1971, Geoffrey Bardon, a teacher in the community, encouraged the children to paint a mural in the traditional style of body and sand ceremonial art. This painting style was used for spiritual purposes and had strict protocols for its use. The symbols depicted personal totems and Dreamings, as well as more general Dreamtime creation stories. [Source: Wikipedia]

When some of the elders saw what the children were doing, they decided that the subject matter was more appropriate for adults. They started creating a mural depicting the Honey Ant Dreaming. Papunya is traditionally the epicenter of the Honey Ant Dreaming, where songlines converge. Later, the European-Australian administrators of Papunya painted over the murals. which the curator Judith Ryan called "an act of cultural vandalism", noting that "the school was de-Aboriginalized and the art no longer allowed to stand tall and defiant as the symbol of a resilient and indomitable people".

Geraldine Brooks wrote in The New Yorker: There are plant species indigenous to Australia, such as the Hakea bakeriana, that bear fruit only after the extreme stress of drought or bushfire; the flowering of Aboriginal contemporary art is a similar phenomenon. After the Australian government adopted a policy of assimilation, in the early fifties, nomadic Aborigines were forcibly resettled in Papunya. The government offered the town’s black residents squalid housing that was meant to facilitate their integration into white society. In 1971, a white schoolteacher named Geoffrey Bardon arrived in town and discovered a place of disease, violence, and despair. Papunya was, he later wrote, “a death camp in all but name.” [Source: Geraldine Brooks, The New Yorker, July 20, 2003]

As part of his instruction, Bardon gave his pupils a small supply of acrylic paint. It was not the students, however, but the town elders who seized upon this new material. Adult Aborigines, still reeling from displacement and facing the threat of cultural annihilation, used the paint to make a lasting record of designs and images that had previously been used only in clan ceremonies. For the first time, the ancient iconography of desert Aborigines was rendered in modern mediums. At Papunya, the pictorial vocabulary of ground paintings was transferred from ochers to acrylics and from desert earth to concrete walls. The graphic symbols have multiple meanings. Concentric circles can represent sacred rocks, campsites, or campfires. U-shapes signify both humans and spirit beings. (This symbol is derived from the shape left in the sand by a person sitting cross-legged.) Bardon was delighted by what the Aborigines created. He encouraged the artists, and brought them boards and canvas. He could not satisfy the Aborigines’ demand, however. Within a few months, almost every flat surface in the village, from old fruit boxes to hubcaps and floor tiles, was covered with acrylic paint.

Development of Papunya Aboriginal Art

While visible, the mural proved highly influential, leading other men to create smaller paintings of their Jukurrpa (Ancestral stories), on any available surface, including bits of old masonite, tin cans, matchboxes and car parts. This explosion of artistic activity is widely considered the origin of contemporary Indigenous Australian art. [Source: Wikipedia]

The collective, founded in 1972, was originally composed entirely of Aboriginal Australian men. The name “Tula” came from a small hill near Papunya, a Honey Ant Dreaming site. Between 1973 and 1975, the Papunya Tula artists began to conceal overt ceremonial references in their work, revealing less of their sacred traditions. The openness of the Bardon era came to an end, and dotting and overdotting emerged as a means of disguising or covering secret designs. The art presented to the public was thus diluted for exhibition, underscoring the singularity of Geoffrey Bardon’s years—a moment of innocence that could not be recaptured.

A few women, notably Pansy Napangardi, began to paint for the company in the late 1980s. It was not until 1994 that women generally began to participate. Most of the artists had never previously worked in Western mediums such as acrylic paint on board or canvas. As their work grew in popularity, artists altered or omitted spiritual symbols for public display, responding to criticism from within the Aboriginal community that too much sacred knowledge was being revealed.

Following the passage of the Aboriginal Land Rights Act in 1976, many people left Papunya in the late 1970s and early 1980s to return to their ancestral lands, yet the art cooperative endured and expanded. For years, however, the broader art market and major institutions largely overlooked their work. An important exception was the Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory (MAGNT), which, through the foresight of its director Dr. Colin Jack Hinton and Alice Springs gallery owner Pat Hogan, assembled the nation’s largest collection of early Papunya works—over 220 paintings produced between 1972 and 1976. As of 2008, this remained the most substantial collection of its kind. The National Gallery of Victoria did not acquire any works until 1987, when curator Judith Ryan persuaded the director to purchase ten paintings. At the time, the cost was A$100,000—an amount Ryan later described as “a steal,” given the dramatic rise in market value.

Early Aboriginal Art Scene in Western Australia

Geraldine Brooks wrote in The New Yorker: Another transformation occurred around the same time, hundreds of miles away, in the area south of Fitzroy Crossing. The Great Sandy Desert had been of little interest to white cattle ranchers, and traditional Aboriginal life survived there well into the fifties. Skipper and Chuguna, the Mangkaja artists, were both young adults before they encountered a white person. Skipper, a self-confident man in his seventies whose salt-and-pepper beard extends to his impressive belly, recalled his first brush with the modern world: when he was a teen-ager, an automobile passed within view, and Skipper ran and hid in the bush—afraid that the large eyes of the strange beast might be able to see him. [Source: Geraldine Brooks, The New Yorker, July 20, 2003]

Chuguna recalled that living in the desert had been difficult. In the dangerous heat of the dry season, many mothers would leave their toddlers in a shady place alongside a water-filled bark bowl, while they foraged for miles on the blistering sand, gathering wattle seeds or ant eggs. In the late fifties, she said, there was a drought, and clan members began to suffer from malnutrition. Skipper and Chuguna, who had just married, left home, walking north in search of work on white-owned cattle stations.

During the sixties, ranchers began pushing blacks out of the ranching industry, and Aborigines throughout Western Australia drifted toward the fringes of white towns, which offered little work and plenty of alcohol. Fitzroy Crossing, where Skipper and Chuguna finally settled, in 1970, was such a place; Turkey Creek, to the northeast, was another. It was in Turkey Creek that an artistic revival parallel to the one at Papunya began.

Aboriginal Arts Gains an Wider Audience

Geraldine Brooks wrote in The New Yorker: In 1988, one of Skipper’s paintings was sent to New York for the Asia Society’s exhibition “Dreamings: The Art of Aboriginal Australia.” The show drew the largest attendance ever at the society, and its enthusiastic critical reception began to change the way Aboriginal art was viewed. Although the paintings were informed by thousands of years of tradition, they were hardly folk art. Indeed, the Aboriginal artists seemed rather postmodern: painters like Skipper had cleverly appropriated old imagery in order to create something new. [Source: Geraldine Brooks, The New Yorker, July 20, 2003]

In 1994, Sotheby’s ratified this emerging view by including Aboriginal paintings in an exhibition of contemporary art. Until then, Aboriginal works had always been grouped with ethnographic curios. The paintings attracted bidding from all over the world. Sotheby’s department of Aboriginal art has since blossomed; this year, sales are expected to reach four million dollars.

High Prices for Aboriginal Art

Geraldine Brooks wrote in The New Yorker: Tim Klingender, the Sotheby’s expert who mounted the 1994 exhibit, divides his energy between Sotheby’s clients—whom he calls “the richest two hundred thousand people on the planet”— and Aboriginal communities, where the living conditions and the life expectancy rival those in the most dismal outposts of the developing world. At gallery openings, Klingender talks about Aboriginal art with a slick marketer’s spin; at home in Sydney, he speaks earnestly about his efforts to champion a culture once viewed as pathetic and doomed. [Source: Geraldine Brooks, The New Yorker, July 20, 2003]

Sotheby’s draws criticism from Aborigines and others who believe that artists should get a resale royalty on the sometimes staggering sums achieved at auction. The Papunya artist Johnny Warangkula Tjupurrula, for example, sold his canvas “Water Dreaming at Kalipinypa” for seventy-five dollars to a visiting artist in 1972. It ended up hanging in the owner’s laundry shed, just above the washing machine. In 1996, the owner of the painting asked Klingender to evaluate the work. Warangkula’s painting, he declared, was “a total masterpiece”; the work’s meshlike layering of stippled dots only partly veiled secret ceremonial objects and symbols that would become fully obscured in later Papunya works.

Klingender’s sales pitch was effective: Sotheby’s sold “Water Dreaming” at auction in 1997 for a hundred and fifteen thousand dollars; in 2000, it sold the work to a New York collector for two hundred and sixty-three thousand dollars. Warangkula, who died in 2001, received nothing from either of the sales, even though at the time he was crippled, partially blind, and destitute. Klingender told the Aboriginal community that the sales had revived interest in Warangkula’s art, allowing him to make a good living in his final years. The curator also organized a charity auction that raised funds for a dialysis clinic near the remote community of Kintore, where Warangkula died.

Mangkaja Arts Resource Agency in Western Australia

The Mangkaja Arts Resource Agency, an Aboriginal coöperative, is located in Fitzroy Crossing, a small town in the Kimberley region of Western Australia, 400 kilometers (250 miles) east of Broome. Describing it in the early 2000s, Geraldine Brooks wrote in The New Yorker: It “is housed in an unprepossessing strip of metal buildings, next to a supermarket and a take-out food shop. The sky was gray on the February day when I arrived for a visit, but inside the coöperative two adjoining rooms were abloom with color. Vibrant paintings occupied every inch of wall space and were stacked in piles on the floor, ready for shipment to forthcoming exhibitions in Sydney, Darwin, and Perth. A large canvas by one of the center’s best-known artists, Pijaju Peter Skipper, dominated a far wall. The principal color of the painting is red, in homage to the soil of the artist’s birthplace, and the canvas is stippled with dots and cross-hatchings that call to mind the patterns of wind on sand or the minute tracks of lizards. Bisecting this elaborate field is a set of darker, more prominent tracks: human ones. The painting is called “Walking Out of Country,” and it is Skipper’s lament for the exodus of his people, the Walmajarri, from their homeland in the Great Sandy Desert, a parched expanse south of Fitzroy Crossing. [Source: Geraldine Brooks, The New Yorker, July 20, 2003]

Not far from Skipper’s large painting hung a work by his wife, Jukuna Mona Chuguna, a handsome woman whose high cheekbones are framed by a tumble of lustrous curls. The theme is the same—lost country—but whereas Skipper had applied his paint in exact, economical dabs, Chuguna had swept hers onto the canvas in wide gestures that recall the way thick ocher body paint is applied by thumb onto the breasts of women dancers in clan ceremonies. Her work evokes, but does not mimic, the action paintings of mid-twentieth-century American artists.

In Walmajarri, one of the five Aboriginal languages spoken in the Fitzroy area, a mangkaja is a makeshift shelter of sticks and grass thrown up for protection against the rains of the wet season. The Mangkaja Agency, which was founded in the early eighties, got its name because the first art-related structure in Fitzroy was a concrete-and-tin shed by the roadside, which was paid for by a small government grant. It was thought that unemployed and idle Aborigines could carve boomerangs there and sell them for a few dollars to passing tourists. Instead, the Aborigines started painting, and became part of a creative revival that has reshaped Australian art and drawn record crowds at exhibitions abroad.

At any time of day, the agency is a bustling place. The atmosphere is part studio, part day-care center, part old people’s home. An elderly woman named Dolly Snell sat cross-legged on the floor in front of a three-foot-square canvas, applying thick rondelles of yellow acrylic in patterns that resembled spinifex, a sharp-bladed desert grass. Her giggling grandchildren played tag all around her, their swift feet sometimes cutting across the canvas, perilously close to the wet paint. Snell didn’t appear to mind. In one corner, another artist, Hitler Pamba, captivated an older group of children with an account of his childhood in the desert. (Hitler is Pamba’s “station name,” the bleak joke of a white boss for whom Pamba once worked as a cattle drover.)

Speaking in a mixture of Wangkajunga, Walmajarri, and Aboriginal “Kriol” English, Pamba told the children how he had recently visited the region where he grew up, which was dotted with salt pans, the dried-out remnants of ancient lakes. “No one’s lived there for sixty years, but when I got there I could still see our tracks leading across all that salt to the place where we got water,” he said. When Pamba paints, his pictures often re-create this abandoned landscape: opalescent expanses of bluish white are pierced by a green swirl that represents the vegetation surrounding the water hole.

Where the Mangkaja Artists Live

Geraldine Brooks wrote in The New Yorker: Bayulu, about 16 kilometers (10) miles from Fitzroy Crossing, is a settlement where several of the most prominent Mangkaja artists, including Skipper and Chuguna, live in bleak, unpainted concrete-block houses, their glassless windows barred in response to break-ins by local drunks and drug addicts. [Source: Geraldine Brooks, The New Yorker, July 20, 2003]

In such communities, the earnings of someone like Skipper, who paints irregularly and might make fourteen thousand dollars in a good year, are divided and shared by an extended family; many residents have no income beyond welfare checks. Skipper and Chuguna also have community responsibilities that limit their artistic output. Skipper, as an elder, is often called away on secret ceremonial business. Chuguna teaches the Walmajarri language at the community school.

A sign at the entrance to Bayulu proclaimed that no alcohol or gambling was allowed in the settlement, but as Klingender’s vehicle churned up the muddy road, scattering packs of skinny dogs, several outdoor card games were in progress. Skipper was engrossed in one of them. The artists’ houses were as modest as those of their neighbors, but many of them had used their extra income to purchase refrigerators and washing machines, as well as four-wheel-drive vehicles. Klingender told the artists about the next day’s meeting, and offered to arrange transport for those who needed it.

How Australian Aboriginals Feel About Selling Their Art

Geraldine Brooks wrote in The New Yorker: Aboriginal painting has become popular with gallery owners throughout Australia, and Pamba and the other members of the Mangkaja coöperative are able to sell much of what they produce. In 2003, the sale of works by Mangkaja’s fifty painters brought in more than a quarter of a million dollars. The additional income is certainly welcome, but it has not alleviated the poverty of the local Aboriginal community, which includes some twelve hundred people. [Source: Geraldine Brooks, The New Yorker, July 20, 2003]

For this reason, the artists in Fitzroy Crossing began a difficult discussion. Perhaps it was time, some suggested, to sell a pair of beloved canvases, “Ngurrara I” and “Ngurrara II.” These densely detailed paintings, which were the joint creation of dozens of local artists, are widely considered to be masterpieces. (Ngurrara, which means “country” in Walmajarri, is pronounced nur-ara.) The paintings share surface similarities with Western abstract art—they have the energy of a Pollock, the exuberant colors of a Matisse, and the fanciful geometric forms of a Miró—yet they are also intricate narrative works that relate detailed stories about the lives of the artists’ ancestors. The sale of these celebrated paintings, experts had said, could bring in a tremendous amount of money.

The Aborigines would not find it easy to allow these singular records of local history to be shipped thousands of miles away. Then again, the Outback is not an ideal place to preserve fragile works of art. During a visit to a flimsy prefab bungalow near the Mangkaja center, I had my first glimpse of “Ngurrara II.” “I’m ashamed for you to see how we are storing it,” Karen Dayman, who works as an adviser at Mangkaja, told me. The canvas, which is twenty-six feet wide, had been rolled up inside a rough-hewn wooden crate. This makeshift container had been propped up on plastic milk crates to protect the painting during the monsoon season. Last year, it was endangered by a flood. “The water was almost up to the top step of the house,” Dayman said. This year’s wet season had begun, and, as we talked, a hard rain drummed on the bungalow’s tin roof and fell in curtains around the veranda.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, National Museum of Australian

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Culture Shock! Australia, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated October 2025