Home | Category: Aboriginals

SEX IN ABORIGINAL SOCIETY

A traditional Aboriginal view of sexuality is that it is a natural urge to be satisfied. It has symbolism beyond the individual, being linked to fertility in all its manifestations. Sensitivity on sexual matters has precluded any extensive anthropological study. The major, detailed work is that of Ronald and Catherine Berndt, who spent more than 30 years observing, participating, and documenting Aboriginal cultures in the northern regions of Australia. [Source: Rosemary Coates, Ph.D.. Dr. Robert Tonkinson, Professor of Anthropology at the University of Western Australia International Encyclopedia of Sexuality, edited by Robert T. Francoeur, Continuum International Publishing Group, 2004, online at the Kinsey Institute \^/]

In song and dance, intercourse and erotic play is celebrated as joyful and beautiful. Intercourse has significance as it maintains populations, both human and nonhuman, and therefore produces food. It is through intercourse that the seasons come and go, and it is only through the changing of the seasons that plants can grow.\^/

The use of songs, dances, and other rituals were used to attract a prospective lover or to rekindle passion in an existing relationship. members of either sex employed love magic, which was thought to cause the person who was the object of it to become filled with desire. On occasions, a large-scale ritual dance of an erotic nature was used as a general enhancement of sexuality. Both sexes were involved, although the pairs of dancers who simulated intercourse were of the same sex. The intention, however, was aimed at arousing heterosexual desires .\^/

Representations of sex, through songs, dances, and paintings, relate to the human activity and to seasonal change, to the growth and decay of plants, and to the regeneration of nature. Reproduction of humans and of the natural world is vitally important, and obedience to ancestrally ordained laws is the responsibility of adult humans. The correct performance of rituals guarantees continuity of life-giving power and fertility.

Puberty Rituals initiation ceremonies assisted the transition from childhood to adult hood with highly elaborated rituals for boys. Modeled on death (of the boy) and birth (of the man) they dramatized separation from women, in particular from the mother. Rules of kinship dictated the allocation of roles and responsibilities in initiation as in all social behavior. Guidance, reassurance, and support were guaranteed, as was chastisement if rules were broken. For females, puberty rites were simple. The transition to adulthood was based on sexual maturation and included sexual activity. However, menarche, marriage, and childbirth have not been ritualized or publicly celebrated in Aboriginal societies.\^/

RELATED ARTICLES:

ABORIGINAL MEN AND WOMEN: GENDER, MARRIAGE, SEX ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL CUSTOMS, SOCIETY AND RITUALS ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL LIFE: WHERE THEY LIVE, WORK, DIET, HEALTH, ALCOHOL ioa.factsanddetails.com

TRADITIONAL ABORIGINAL LIFE: FOOD, HOMES, HUNTING ioa.factsanddetails.com

LIFE OF EARLIEST HUMANS IN AUSTRALIA: TOOLS, WEAPONS, ART, SETTLEMENTS ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL RELIGION: TRADITIONAL BELIEFS, DEMOGRAPHY AND DEATH ioa.factsanddetails.com

RITUAL LIFE AND MYTHS OF ANCIENT AUSTRALIANS ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIAN ART ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS (FIRST NATION PEOPLE) OF AUSTRALIA: NAMES, DEMOGRAPHICS, LANGUAGES ioa.factsanddetails.com

EARLY MODERN HUMANS IN AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINALS AT THE TIME EUROPEAN COLONIZATION BEGAN ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIA ABORIGINALS FROM 1900 TO PRESENT: DISCRIMINATION, ASSIMILATION, SOME RESTITUTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIA’S STOLEN GENERATIONS: VICTIMS, LAWS, RATIONALE, OUTRAGE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS IN QUEENSLAND: SOME GROUPS, CUSTOMS, LIFESTYLES ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIANS IN NORTH NORTHERN TERRITORY: SOME GROUPS, CUSTOMS, LIFESTYLE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS OF CENTRAL AUSTRALIA: SOME GROUPS, CUSTOMS, ART, LIFESTYLE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS IN WESTERN AUSTRALIA: SOME GROUPS, HISTORY, CUSTOMS, TRADITIONAL LIFE ioa.factsanddetails.com

Aboriginal Ritualistic Defloration

Ritualistic defloration was practiced in some parts of Australia, but no longer occurs. According to “Growing Up Sexually: Introcision (the enlargement of the vaginal opening by tearing or cutting the perineum) was practised among some of the aboriginal Australians (Aranda, basically) in order to facilitate the first experience of sexual intercourse, which may have been immediate, forceful and with multiple partners. When a young woman of the Queensland tribes shows signs of puberty, two or three men take her away, and she has to submit to intercourse with all. After this, she is considered eligible for marriage. The Spinifex group also practised ritual hymenotomy, but did not include ritual intercourse. The pubic hairs are shaved to “make it nice and ready for coitus”. Its timing was after menarche, at age 14 to 15 (Drechsel). [Source: “Growing Up Sexually, Volume” I by D. F. Janssen, World Reference Atlas, 2004]

Ceremonies varied. One example dating back to the 1940s, was described by Berndt, and related to people from the north eastern region of Arnhem Land. Girls who were to undergo the ritual were called “sacred” and deemed to have a particularly attractive quality. The men made boomerangs with flattened ends, to be used as the instrument of defloration prior to ritualistic coitus. [Source: Rosemary Coates, Ph.D.. Dr. Robert Tonkinson, Professor of Anthropology at the University of Western Australia International Encyclopedia of Sexuality, edited by Robert T. Francoeur, Continuum International Publishing Group, 2004, online at the Kinsey Institute \^/]

Men, girls, and boomerangs were smeared with red ocher, symbolizing blood. A special wind break or screen was prepared for the girls, the entrance of which was called the sacred vagina. The screen was intended to prevent men from seeing “women’s business.” Prior to her defloration, a girl may have lived in seclusion for a period of time with certain older women, observing food taboos. The older women taught the girls songs, dances, and sacred myths. At the end of the seclusion period, there was a ritual bathing at dawn.

In some areas, a girl may have lived in her intended husband’s camp for a period of time. after the seclusion period, she would be formally handed over to her husband and his kin, and the marriage consummated. In other areas, a girl may have been unaware that her marriage was impending and be seized by her intended husband and his “brothers” while she was out collecting food with the older women. Her husband’s “brothers” had sexual rights to the girl until she had settled down in his camp.\^/

Earlier anthropological reports described rituals that have involved the forced enlargement of the vagina by groups of men using their fingers, with possum twine wound round them or with a stick shaped like a penis. Several men would have intercourse with the girl and later would ritually drink the semen. Mitigating this was the second part of the ritual which allowed dancing women to hit men against whom they had a grudge with fighting poles without fear of retaliation.\^/

Aboriginal Circumcision

Circumcision was a common, though not universal, practice. In many areas, Aboriginal men believed that the uncircumcised penis would cause damage to a woman, which was one reason why sexual activity of an uncircumcised boy was viewed negatively. Rituals associated with circumcision were secret and sacred and were considered “men’s business.” Full details have not been disclosed to outsiders. [Source: Rosemary Coates, Ph.D.. Dr. Robert Tonkinson, Professor of Anthropology at the University of Western Australia International Encyclopedia of Sexuality, edited by Robert T. Francoeur, Continuum International Publishing Group, 2004, online at the Kinsey Institute \^/]

Circumcision knife with quartzite blade and gum handle, from near Macdonnel Ranges, Central Australia, 1850-1920, from Science Museum Group

Women danced close to the circumcision ground but were not permitted to watch. During totemic rituals, the boy who was about to be circumcised was present, but often could not see what was going on. It was at that time that he was told the meaning of the songs. Just before dawn, he would be led to a group of older men who used their bodies to form a “table” upon which the young boy was placed. After the Circumcision, the boy returned to his seclusion camp and the rest of the group moved to an other camp site, as happened after a death. In some areas, the fore skin was eaten by older men, in others the boy wore it in a small bag around his neck; in others it might have been buried.\^/

“There were a number of post-circumcision rites that included the young man’s being taken on a journey around his totemic country. At a later stage, subincision ( a procedure where the underside of the penile urethra is incised, primarily documented among certain Australian Aboriginal groups) may have taken place. Again, the initiate was taken into seclusion and, later, the procedure conducted using the human “table.” The partially erect penis was held up and the incision made on the under side. Subincision of the penis was regarded as the complementary right to defloration.

Stone blades were prepared while thinking of coitus, and it was believed that semen flowed more rapidly after subincision. Subincision had religious validation, proved in many areas through reference to the penile groove of the emu or the bifid penis of the kangaroo. Subincision was not for contraceptive purposes, as was commonly believed by nonindigenous people. In fact, in many areas, semen was not credited with having a role in procreation. In all areas of Australia, spiritual forces were believed to be central to procreation. Physiological maternity, as well as paternity, was denied, with the belief that a plant, animal, or mineral form, known as the conception totem, was assumed by the spirit-child, who then entered its human mother .\^/

See Initiations Under AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL CUSTOMS, SOCIETY AND RITUALS ioa.factsanddetails.com

Adolescent Sex Among Aboriginals

According to “Growing Up Sexually: “ The original Australians were famous for their coital precocity. Eyre (1845) noted that “the life of an Australian woman is nothing more than uninterrupted prostitution...From age ten she has intercourse with boys of 14 and 15. Howitt (1891) quotes O’Donnell on the Kunandaburi tribe: “Female children during their infancy are given by their parents to certain men or boys, who claim them as soon as they arrive at puberty, and often before”. The marriage is then consummated by the “Abija”, who helps dragging her away, and subsequently, by “all males in the camp...not even excepting the nearest male relatives of the bride”, in a ceremony lasting for days. Thus, Howitt (1904) seemed to have assumed that prepubertal intercourse did not customarily exist in Australia. [Source: “Growing Up Sexually, Volume” I by D. F. Janssen, World Reference Atlas, 2004]

This may well be true judging from the marital context. As mentioned by Taplin (1879) among the southern Kukatha tribe no sexual intercourse occurred until after puberty. The age of native marital consummation was judged to be between 14 and 15 (Spencer and Gillen, 1899) and between ten and twelve (Malinowski, 1913). On the other hand, premenarchal coitus in Australia was assumed to be common by Fehlinger ([1921) and mentioned by Piddington (1932) for the Karadjeri (Western Australia). Stanner (1933) reports for North-Eastern (DalyRiver) tribes that although “sexual relations are not supposed to take place before puberty”, a betrothed girl may stay in camp with her future husband until this takes place. Anyway, “even before puberty children are making crude sexual experiments”.

Snake is an Aboriginal condom brand

Drechsel (1985) states: "Before the onset of puberty and the beginning of male initiation, young people lead a fairly unconstrained life, almost anti-authoritarian in our sense. They practice mimetic sexual behavior from an early age. The adults encourage this, and it serves them as a source of amusement. Sexual contact before puberty is common. However, with the onset of initiation, the young men's casual sex life is supposed to end. According to the agreements, the girls are handed over to their promised husbands at around the age of nine, who gradually instruct the girl in marital duties over the next few years."

Adultery is condoned according to the institution of the so-called “Love Magic”, or more precisely, the Wongi institution, as it used to be widely distributed on the continent. Wongi relations would begin at age 14 for boys and age 11 for girls. Róheim for the Aranda: “Let us suppose that a little girl has been promised to a man who is about the age of her father. She is his noa of course, according to the classificatory system of relationship, but he will not have intercourse with her till the signs of puberty become noticeable. These are: the development of the public hair, the breasts and, in a minor degree, the first menstruation. From time to time he will visit his bride and grease her, this being regarded as a sign of his love, as a sort of caressing and as a magical proceeding to make her breasts grow”.

Maddock ([1972) conveniently sums up some later observations on “coitarche” age: “A Tiwi girl took up cohabitation when eight or ten according to Jane Goodale (1962), fourteen according to Hart and Pilling (1960); a Walbiri when nine or twelve (Maggitt, 1962, 1965), a Wanindiljaugwa when nine (Rose, 1960); and a Pidjandjara, among women married first at an unusually late age, when in her late teens or even early twenties (Yengoyan, 1970). The husband would probably have reached forty in Tiwi, thirty if Walbiri or Wanindiljaugwa and the late twenties if Pidjandjara”. Curr (1886), speaks of cohabitation at age eight, Sadler at age ten. Von Miklucho-Maclay (1880) speaks of age stratified sexual intercourse with girls before puberty.

Exploring contemporary Australian Aboriginal adolescent sexualities, Burbank suggests that the girls’ sexual and reproductive freedom is supported by the confluence of three factors: diminished force of ideologies that might circumscribe women’s behaviour, control of male violence, and cultural appreciation of both motherhood and children.

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see “Growing Up Sexually, Volume” I by D. F. Janssen sexarchive.info

Sexual Knowledge and Play Among Aboriginal Children

According to “Growing Up Sexually: Genitalia and sexual maturity are important organising factors in everyday life; menarche, thelarche, beginning of puberty, and ejacularche are commonly referred to by children as indicating age or age difference. Boys are (probably playfully) insulted by the exclamation kalu (penis) alputalputa (dry boy’s grass), which, according to Róheim (1938) is “slanderous as it indicates that the boy’s penis is devoid of semen”. [Source: “Growing Up Sexually, Volume” I by D. F. Janssen, World Reference Atlas, 2004]

Lacking a substantial (conscious) association with conception, many of the Australians regard all intercourse in the light of play. However, Strehlow remarks that both Arunta and Leritja tribes enlightened their children on the reproductive cycle of animals. The matter of conceptive knowledge is discussed by Read (1918) who argues: “That among many savages [sexual] intercourse is common before puberty, and therefore resultless, seems to me unimportant; because the change of sexual life at puberty is deeply impressive and well known to savages”. I may remark here that this point awaits exploration. The idea may indeed be fostered by an absence of coital pause since childhood, combined with the observation that, for reasons not clearly understood, “the girls seem to be sterile for several years after puberty” (Wallace, 1961).

Richter (1962): reports: "As long as the children are still small, sexual play takes place in public. Later, boys and girls take advantage of the adults' quiet hours to sneak into the bushes, play man and woman, and exchange experiences. At the age of 9, sometimes even earlier, little girls have their first sexual intercourse; they are therefore 2 to 3 years before menarche. Their first partners are usually older, already initiated boys... The girls often dilate their hymens with their fingers themselves or with the help of a friend... Mutual masturbation between women and girls is widespread... The occurrence of pederasty has also been documented, with 17- to 18-year-olds often taking 10-year-old boys as lovers to bridge the time until marriage."

Children learn about sexual relations “in broad outline” at a “very early” age (Berndt and Berndt, 1971): “Sometimes children play at “husbands and wives” with separate windbreaks, making little fires and pretending to cook food. Sometimes there are games of adultery, one little boy running off with the wife of another”. Kinship codes are enforced leniently. Berndt and Berndt (1946) wrote: “Very small children try to carry out among themselves actions similar to those of their parents during coitus...Parents will joke about their children’s genitalia or immature erotic experiments, or ignore them as they feel inclined. Dozens of such examples from various parts of southern, central, and northern Australia might be cited if space were available...a boy of three or four years will call out in fun (knowing that he will provoke amusement from adults) that he wants to copulate, while an older girl will lift him up under the armpits, saying, “Ah, you want to [copulate] ‘longa me? Come on, [copulate], make ‘im long one ‘longa me”- at the same time lifting and rubbing him against the front of her body to the diversion of all concerned”. Hippler (1978) also observed that “intersexual play occurs...pelvic thrusting and lying on one another as well as genital manipulation are common”.

Tonkinson (1974) “Even their [preschoolers] periodic attempts to imitate the sexual activities of their elders are viewed by the latter with light-hearted indifference and do not provoke adult interference” Berndt and Berndt (1951) in Arnhem Land repeatedly sketched the attitude configuration typical of many Oceanic people: “When such activities are carried out in play with children of the same age or older, they usually cause much merriment among the onlookers, who make lewd and suggestive comments. The fact that such erotic play serves as a sexual stimulant to the children does not seem unduly to worry the adults, who say placidly: “He’s to young to have an erection”, or “Why, that child has only a small vagina, she won’t be ready yet for a long time”. Intercourse, however, may have been encouraged when “children...are invited by a mother, older brother or sister, or some other person, to indulge in sexual intercourse with an adult or a child of the same age”.

Influence of White Society on the Sexual Play of Aboriginal Children

Tonkinson (1974) relates that missionaries set up dormitory systems to break up the coital quests, with only partial success. This was already observed by Lommel (1949): “Sexual intercourse starts at an early age, but is frowned upon by older people, as it should begin only after initiation. On the stations and missions old people lose their influence on the younger and alert persons who are able to understand the new law which is brought by the white men”. [Source: “Growing Up Sexually, Volume” I by D. F. Janssen, World Reference Atlas, 2004]

Still, “there exists a special expression for sexual intercourse between young boys and girls: jan jan (Unambal and Worora tribe)”. By the time of 1981, a report by Hamilton[83] (p76, 104) suggests that coital play may have gone underground (or rather, bushward): “No activities that could be called “sex play” were ever observed in the camps and there was nothing to suggest that if they occurred out of sight of adults anyone was concerned...Adults deny the occurrence of homosexual play among the boys [ages 5-9] although they admit to heterosexual play between children before they can “understand”.

In 1935, Kaberry would warn that “[s]ome missionaries have yet to grasp the elementary fact that needle work, cooking, housework and an occasional picnic do not in themselves constitute an adequate substitute for sexual experience”. Despite these attractiva, Kaberry (1939) could report that “[c]hildren of both sexes romp together, fight, squabble, wrestle, and indulge in crude sexual play...young girls of eight or ten play with the boys in the camp when the others are asleep at midday or away in the bush”. By the 1980s, Cowlishaw refrains from discussing sexual behaviour socialisation altogether. This is remarkable given his earlier PhD thesis on the matter.

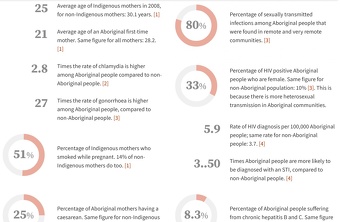

Aboriginal Australian Contraception and Sexual Abuse

In the past, Australian Aboriginals, like other hunting and gathering societies, had low levels of fertility. Ethnographers have found little evidence of plant contraceptives or abortion agents. There is no evidence of infanticide ever being used. Today, in addition, to the services available to all Australians, there are a number of family planning services specifically set up for Aboriginal populations. These include infant and maternal health and welfare services, fertility counseling, and STD and HIV/AIDS education programs. [Source: Rosemary Coates, Ph.D.. Dr. Robert Tonkinson, Professor of Anthropology at the University of Western Australia International Encyclopedia of Sexuality, edited by Robert T. Francoeur, Continuum International Publishing Group, 2004, online at the Kinsey Institute \^/]

There is current concern that the incidence of child sexual abuse is increasing among the Aboriginal population. This may well be as a consequence of dislocation from traditional social structures. Kin relationships, rather than a biological ones, have traditionally dictated the incest taboo . In traditional societies, the incest taboo extends to all the members of one’s own moiety, with certain exceptions during sacred rituals. For example, during the defloration ceremony, a man inserts the defloration boomerang into a woman whose formal relationship to him is roughly the equivalent of his wife’s mother; he then has coitus with her as a sacred ritual considered important from the point of view of fertility.

Hiatt (1965): quotes the experience of a man who, presumably as a child himself, followed four children into the bush: ... The boys used saliva to lubricate the girl’s vaginas. They couldn’t get the penis in. Edgar called Dora “mother”, and Wallace called Charlotte “ZD”, but we were too young to care much about the wrong kinship categories. We just copulated with anyone. But I thought to myself, “The mother of those girls will be every angry when they find out what they’ve been up to” ”.

Aboriginal Australian Homosexuality

The Berndts (1988) commented that the traditional way of life placed so much emphasis on heterosexual relationships that there has been little evidence (to ethnographers) of other modes of sexual expression. They do, however, mention that “homosexual experimentation and masturbation” are reported among boys and young men when temporarily segregated from the women. Berndt goes on to say that examples of female homosexuality is even more rare and that “the close physical contacts which Aboriginals indulge in are deceptive in this respect”. Contemporary urban life has demonstrated that homosexuality is known among the Aboriginal community, with gay and lesbian Aboriginals participating in the local gay culture. There is no evidence in the literature of transgender desires in traditional Aboriginal cultures. [Source: Rosemary Coates, Ph.D.. Dr. Robert Tonkinson, Professor of Anthropology at the University of Western Australia International Encyclopedia of Sexuality, edited by Robert T. Francoeur, Continuum International Publishing Group, 2004, online at the Kinsey Institute]

According to “Growing Up Sexually, Volume” I: "Girls sometimes masturbate by themselves or with other girls. Pre-adolescent boys sometimes chase the girls who allow themselves to be caught. the boys then fondle the girls' breasts and genitalia. The girls take pleasure in this kind of sexual play, [and no doubt also the boys!] Nowadays, out in the bush or of a night, girls sometimes request boys to play with them in this way with remarks such as "Turuparni!" (No bloomers!) or "Feel me. I've got nothing underneath."...Some younger people practise mutual masturbation, but this is not homosexuality...Boys masturbate by themselves and also with other boys. Frequent opportunity for mutual masturbation occurs during the cold time of the year. Youths are usually segregated from their families in the camp. They come into close bodily contact with each other when they sleep together near their small fires. Older boys sometimes rape smaller boys.Youths also practise anal intercourse in the prostrate or sitting positions. On occasions, young men play with the prepuce of small boys, pulling it out like a rubber band. Boys also do this with their own penes". [Source: “Growing Up Sexually, Volume” I by D. F. Janssen, World Reference Atlas, 2004]

Róheim (1950): “Homosexuality plays a conspicuous role in the life of a young girl [using] little sticks wound around at the end so as to imitate the glans penis...All the virgin girls do this...One of them plays the male role and introduces the artificial penis into her cousin’s vagina...they then rub their two clitorises together...At the age of eight or ten boys and girls frequently have their own little houses...They do it first to their little sisters. Sipeta says that her older brothers every evening before they went to the girls would pet her this way”.

Aboriginal Australian Boy-Wives

According to “Growing Up Sexually: A boy-wife system is known to have existed among the Aboriginal Australians around the end of the nineteenth century (Murray, 1992) although its exact homosexual nature or function is variably interpreted. The custom took place with boys until their first subincision, their status designated as Chookadoo (age 5), or Mullawongah (age 5-7). Other authors mention ages of 10, 10-12, and 10-11. The Mullawongah is brought in erection by manipulation, and the penis is inserted into the subincised penis of an elder, who then ejaculates. [Source: “Growing Up Sexually, Volume” I by D. F. Janssen, World Reference Atlas, 2004]

As for the actual performance involved, Mathews (1907) writes: “This custom [boy companions for men] has given rise to a widespread belief among the white population that pederasty is practiced; but from very careful inquiries made by friends at my request, I am led to the conclusion that the vice indulged in between the man and the boy is a form of masturbation only. A resident of the Victoria River informs me that girls who are too young to admit of natural intercourse with them are sometimes used by the men in precisely the same manner as the boys, except that the little girls do not accompany them. I have original descriptions of how the vice is carried out, but the details are not suitable for publication. Mr. E. T. Hardman, during his travels in the Kimberley district of Western Australia in 1883-4, observed the custom of single men being presented with what he calls “a boy wife”. He says: “There is no doubt they have connexion, but the natives repudiate with horror and disgust the idea of sodomy”. Mr. A. G. B. Ravenscroft published some details in 1892 of this practice among the Chingalee tribe at Daly Waters in the Northern Territory, which go to confirm my statement that the indulgence is practically masturbation”.

Rose (1960) mentions no homosexuality as part of the “guardian/initiate institution” among the Groote Eylandt Aboriginals, which practice had broken down around 1940. He does note their social equivalence to girls: “In the same way as a girl is promised as wife to a man, her brother is promised before or shortly after birth to his sister’s prospective husband as an initiate. After the boy is circumcised as about 9 years he goes to live with the older man and remains with him until he is about 17 years old, when he is ceremonially released...The initiates could be stolen, or exchanged as gifts in the same way as young girls could be”.

For more on Boy Wives see “Growing Up Sexually, Volume” I by D. F. Janssen sexarchive.info

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Creative Spirits creativespirits.info

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Culture Shock! Australia, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated September 2025