Home | Category: History / Aboriginals

EARLY ABORIGINALS

Humans are thought to have arrived in Australia about 50,000 to 65,000 years ago. The original inhabitants, who have descendants to this day, are known as Aboriginals to most people. The like to called First Nation people. They developed complex hunter-gatherer societies and oral histories.

In the eighteenth century, the aboriginal population was about 300,000 to 1 million. No one knows for sure. The Aboriginals, who have been described alternately as nomadic hunter-gatherers and fire-stick farmers (known for using fire to clear the brush and attract grass-eating animals instead of cultivating the land), settled primarily in the well-watered coastal areas. [Source: Library of Congress, September 2005]

Little is known about the earliest inhabitants of Australia. They migrated from Asia in numerous waves and have been categorized into two distinct groups: "Robust" and "Gracile." Robust people are believed to have arrived first. Aboriginals are believed to have descended from Gracile people.

Some of the earliest inhabitants of Australia may have been the descendants of Negrito tribes that live today in Malaysia, the Philippines and some Indian Ocean islands. Some anthropologists believe they are descendants of wandering people that "formed an ancient human bridge between Africa and Australia.” Based on fossil remains, prehistoric Australians had bigger builds than modern Negritos.

People were living in the Lake Mungo area, near Melbourne 40,000 to 50,000 years ago. The skulls of these people had thick walls ("Robust"), while those found elsewhere are thin ("Gracile"). This finding has led scientists to believe there may have been two migrations of people to Australia.≤

Related Articles:

DID HUMANS REALLY MIGRATE TO AUSTRALIA 65,000 YEARS AGO ioa.factsanddetails.com

HOW THE FIRST PEOPLE GOT TO AUSTRALIA 50,000 (MAYBE 65,000) YEARS AGO ioa.factsanddetails.com

EARLY MODERN HUMANS IN AUSTRALIA factsanddetails.com ;

OUT OF AFRICA AND THEORIES ABOUT EARLY MODERN HUMAN MIGRATIONS factsanddetails.com ;

MIGRATIONS OF EARLY MODERN HUMANS factsanddetails.com ;

EARLY MODERN HUMANS MIGRATE TO ASIA factsanddetails.com ;

LIFE OF EARLIEST HUMANS IN AUSTRALIA: TOOLS, WEAPONS, ART, SETTLEMENTS ioa.factsanddetails.com

PEOPLE WHO LIVED AUSTRALIA 20,000 TO 10,000 YEARS AGO ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

VERY, VERY OLD AUSTRALIAN AND ABORIGINAL ROCK ART ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT ABORIGINAL ART OF NORTHERN AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

RITUAL LIFE AND MYTHS OF ANCIENT AUSTRALIANS ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN HISTORY ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

MODERN HUMANS 400,000-20,000 YEARS AGO factsanddetails.com

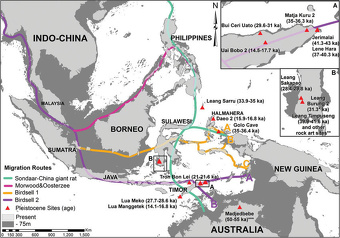

Migration of Early Aboriginals

Four possible migration routes of early modern humans from Southeast Asia to New Guinea and Australia: 1) Southern lines proposed by Birdsell (orange); 2) with western variations (purple); 3) northern route (green) proposed by Sondaar; with 4) Morwood and Van Oosterzee's route (pink) in between; Pleistocene archeological sites (with calibrated ages) are indicated by red triangles

By 35,000 years ago, people had spread throughout Australia, as well as Tasmania and New Guinea, both of which were connected to Australia by land bridges. The oldest human sites in Tasmania have been dated to around 41,000 years ago. Another oldest site in Tasmania, Parmerpar Meethaner, was occupied beginning around 34,000 years ago.

Around 13,000 to 11,000 years ago the last land bridges disappeared and cultures in Tasmania and New Guinea became isolated from those on the Australian mainland. More advanced "microlthic" stone-tool technology appeared on the mainland between 4,000 and 3,000 years ago but never spread to Tasmania. Neither did the dingo, a dog introduced from Southeast Asia about the same time.

The distribution of major archeological sites all over Australia indicates how widely dispersed the early Aboriginals were. They include Madjedbebe (formerly known as Malakunanja), a rock shelter in Arhem Land in Northern Territory; Mirium, a rock shelter on the Ord River in Kimberley in Western Australia; Mt. Newman in the Pilbara region of in Western Australia; the Devil's Lair, near Cape Leeuwin in southwest Australia; Koonalda Cave in the Nullarbor Plains of South Australia; Mootwingee National Park in New South Wales; and the Early Man Shelter near Laura in northern Queensland.

Migration of People from India to Australia 4,000 Years Ago

Ancient Indians migrated to Australia and mixed with Aborigines 4,000 years ago, bringing the dingo's ancestor with them, according to research from 2013. Rosie Mestel wrote in the Los Angeles Times: When modern humans left Africa as far back as 70,000 years ago, they dispersed across the world, reaching Australia at least 50,000 years ago. From then until the 18th-century arrival of European colonists, aboriginal Australians did not mix their DNA with anyone else in the world — or so many scientists believed. Now a study has turned up evidence of much more recent interbreeding between native Australians and people who came from India. The findings, based on a detailed examination of the DNA of aboriginal Australians and hundreds of people of other pedigrees, found that mixing occurred as recently as 4,200 years ago. See Below [Source: Rosie Mestel, Los Angeles Times, January 14, 2013]

Reported in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the results dovetail with interesting archaeological and fossil changes, said study leader Mark Stoneking, a molecular anthropologist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany. Right around that time, new kinds of stone tools called microliths appeared in Australia, finer than earlier tools discovered there but similar to tools already in use elsewhere in the world. Also at this point in time, Australia's wild dog, the dingo, shows up for the first time in the fossil records. Scientists know the dingo is not native to the Australian continent, where all indigenous mammals are marsupials that bear immature young and often carry them in pouches. The dingo, in contrast, is a placental mammal and a subspecies of the gray wolf, like the domestic dog. "We don't know for sure that these events are connected, but the fact that all of these occur at the same time suggests that they may be," Stoneking said. [Source: Rosie Mestel, Los Angeles Times, January 14, 2013]

To reach their conclusions, Stoneking's team conducted a detailed scan of the genomes of 344 people, including Aborigines from the country's Northern Territory as well as people from Papua New Guinea, Southeast Asia, India, China and those of Western and Northern European ancestry. The scientists looked for places where the DNA code sometimes differed by a single DNA building block, or nucleotide, between members of their sample. By noting to what extent individuals shared the roughly 1 million tiny variations that were found, the team could piece together trees that showed how each group of people was genetically related to the others and estimate how long ago the groups had become distinct. They found, for example, that aboriginal Australians, Papua New Guinea highlanders and the Mamanwa people from the Philippines were genetically closest to each other and diverged about 36,000 years ago. This fit well with earlier genetic studies.

But the team was surprised to find — using four separate statistical methods — that a much more recent genetic mixing with people from India had occurred. They estimated that about 11 percent of the DNA of aboriginal Australians is derived from this event. Earlier studies had hinted as much, but they were limited to smaller regions of the genome: the Y chromosome, which is only carried by males, and a type of DNA called mitochondrial DNA that is passed down from mothers to their children, Stoneking said.

The authors of the new study also estimated how far back this genetic mixing had occurred, via the following reasoning: A child born of an Aborigine and an Indian would carry in his or her genome an entire, unbroken stretch of each chromosome, one from each parent. But with each generation, those two chromosomes swap bits and pieces with each other. Down the generations, therefore, the pure Indian or pure Australian chromosome stretches will become increasingly shorter. Using the size and number of DNA stretches in people alive today, the team ran computer simulations to calculate that 141 generations have passed since the initial interbreeding. With each generation assumed to be 30 years, that adds up to 4,230 years.

It isn't clear how the mixing took place. Though it might make sense that the gene flow occurred in Indonesia, no traces of Indian DNA could be found among the Indonesians in the sample and no Indonesian DNA could be found in the Australians, the authors said — perhaps suggesting the migrants came directly to Australia by water. Still, a more detailed analysis of Indonesian genomes would be needed to rule out that connection, Stoneking said.

Early Aboriginal Lifestyle

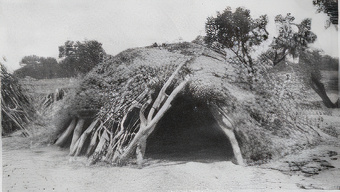

The early Aboriginals are believed to have been hunters and gatherers. The narrative until fairly recently was that they did not farm or build permanent settlement. They didn't use the wheel. Many, it is believed, wandered around barefoot and completely naked. They lived in lean-tos and cooked over open fires. Tools included tertiary-tipped stone tools, grove-edged axes, and boomerangs (the ancient Egyptians also used boomerangs). More recent evidence indicates that least some may have lived in relatively permanent settlement and they may have farmed grain and baked bread 30,000 years and raised eels 8,000 years ago

Early Aboriginals set bush fires to flush game for hunting. In the process they encouraged the growth of new shoots, the food fancied most by animals. They also gathered witchetty grubs from overturned logs, impaled gouanas, and hunted wombats and kangaroos. Early Aboriginals living on the coast ate a lot of mollusks. Evidence of this are huge piles of shells. Some observers believe that bush fires set by aborigines over many centuries may have led to the barren nature of much of the Australian interior. Many kinds of mammals never reached Australia because the land bridge from Asia ceased to exist about 50 million years ago.

Ancient Aboriginal are believed to have moved around in separate family groups or bands. They developed a rich, complex culture, with many languages. They numbered approximately 300,000 by the 18th century; however, with the onset of European settlement, conflict and disease reduced their numbers. [Source: “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations”, 2007]

Eric A. Powell wrote in Archaeology magazine: While on survey in a national park in southern Australia in the mid 2010s, archaeologists discovered a male skeleton eroding out of a riverbank. Dubbed Kaakutja, or “older brother” in a local language, the man had a fatal six-inch gash in his skull. When Griffith University paleoanthropologist Michael Westaway first examined the skull damage, he thought “it looked similar to steel-edged weapon trauma from medieval battles.” But radiocarbon dating of Kaakutja’s skeleton shows he died in the thirteenth century, well before Europeans reached Australia and introduced metal to the continent. Westaway concluded that the wound was likely caused by a heavy war boomerang or a sharp-edged club known as a lil-lil, both of which are depicted in Aboriginal rock art. “Kaakutja’s trauma is unique in that it is the first recorded case of edged-weapon trauma in Australia,” he says. The lack of defensive wounds to the man’s arms suggests he may have been attacked while he slept, which, according to nineteenth-century ethnographic accounts, may have been a common tactic in prehistoric Australian conflicts. [Source: Eric A. Powell, Archaeology magazine, January-February 2017]

Early Aboriginal Tools, Art and Ceramics

Aboriginals are believed to have made most of their tools and dwellings from plant material, and thus most of the remains rotted away thousands of years ago. Most Aboriginal archeological sites reveal stones tools and fireplaces and little else. A necklace made from kangaroos teeth was unearthed from a 12,000-year-old tomb in Kow swamp in northern Victoria. A necklace made from Tasmanian devil teeth was unearthed from a 6,500-year-old tomb at Lake Nitchie in western New South Wales.

A cave is in a remote part of Wollemi National Park, northwest of Sydney. contains 200 paintings, many of them thought to be 4000 years old. They feature humans and rare, godlike half-human, half-animal human-animal composites as well as realistic and symbolic depictions of birds, lizards and marsupials. Australian Museum anthropologist and archaeologist Paul Tacon, who led an expedition to investigate the cavern said there were 11 layers of more than 200 paintings, stencils and prints in different styles, spanning a period from about 2000 BC to the early 1800s. He said the paintings include delicately drawn life-size eagles and kangaroos and an extremely rare depiction of a wombat.

According to Archaeology magazine: Although pottery-making technology existed among some ancient cultures of Oceania, it was long believed that Aboriginal peoples of Australia didn’t produce their own ceramics prior to European settlement. Excavations on Jiigurru, or Lizard Island, located 20 miles off the coast of northern Queensland, have uncovered ceramic sherds made from local clay that are 2,000 to 3,000 years old. This is the earliest example of pottery found in Australia and demonstrates that knowledge of ceramics in the region is far older than previously thought. [Source: Archaeology magazine, July-August 2024]

At Least Some Ancient Aborigines Built Stone Huts and Were Not Nomads

Australia's Aborigines, long considered a nomadic people, appear to have built stone dwellings in the southeast of the country for 8,000 years, according to an archaeologist. The claims are based on finding related to the Gunditjmara people around Lake Condah — about 350 kilometers west of modern Melbourne — made by archaeologist Dr Heather Builth, who found evidence of stone huts scattered across the landscape. She found many stones lay in circular patterns, and were so uniform they could only have been stacked there by humans. [Source: Anna Salleh, ABC (Australian Broadcasting Corporation), March 13, 2003]

Builth is an honorary research associate with Monash University in Melbourne and is also helping produce a management plan for the nearby Winda-Mara Aboriginal Corporation near Lake Condah. Anna Salleh of ABC reported: Although she can not accurately date the huts, there are historical accounts back to 1841 which she has relied on, along with deductions based on what materials would have been available, to postulate the construction of the huts. She said the stone foundations would have had wooden boughs on top, covered with peat sods for strength and reeds for waterproofing.

Ken Saunders, a member of the Guditjmara community, was not surprised at the find. "We weren't nomads. We didn't wander all over the bloody place and gone walkabout. We had an existence here," said Saunders, a member of the Lake Condah Sustainable Development Project, which is seeking National Heritage listing for the area. "Well you couldn't have a blackfella telling that story. So to prove it we had to have a white person doing the scientific research to say this is real," he added. Builth first investigated the theory that the Gunditjamara were sedentary in her doctorate between 1997 and 2002, and has since published a number of scientific papers and presented her work at archaeological conferences.

Aborigines May Have Farmed Eels

Aborigines also appear to have farmed eels at the same Gunditjmara people site around Lake around 8,000 years ago. Builth found what she argues is an ancient eel farm in the form of countless channels crisscrossing the landscape at Lake Condah. "This had to be excavated," said Builth, [Source: Anna Salleh, ABC, March 13, 2003]

The ABC reported: Although the land was drained in the late 19th century when European settlers moved in, Builth measured up every hill and valley in the landscape and used a geography simulation program to 're-flood' the land on computer. She found an artificial system of ponds connected by canals, covering more than 75 square kilometers. "The community excavated channels to get direct access to baby eels that were migrating from the sea, and to bring them into prepared wetlands," Builth told ABC Science Online. "It was a gigantic aquaculture system." More evidence to support Builth's theory about the eel farming and processing was found in the sediments underneath trees and in the remaining swamps near Lake Condah.

Most recently, Professor Peter Kershaw, a Monash University palynologist — or expert in ancient pollen — studied the pollen record in the sediments of swamps identified by Builth as being eel-farming areas. He found evidence of a sudden change in vegetation consistent with an artificial ponding system, and initial radiocarbon dating of the soil samples suggest the ponds were created up to 8,000 years ago.

In addition, Dr Barry Sankhauser of the Australian National University in Canberra used mass spectrometry and gas chromatography, to find evidence of eel lipids in the sediments beneath hollowed-out trees which Builth says were likely to have been used as smokehouses and family cooking hearths. "Guditjmara weren't just catching eels; their whole society was based around eels. And that to me was the proof," said Builth, who argues the community was smoking eels to preserve and trade them.

Budj Bim Cultural Landscape

The eel farms and stone huts described above are in The Budj Bim Cultural Landscape, which was inscribed on the World Heritage List in July 2019. According to UNESCO: The Budj Bim Cultural Landscape, located in the traditional Country of the Gunditjmara people in south-eastern Australia, consists of three serial components containing one of the world’s most extensive and oldest aquaculture systems. The Budj Bim lava flows provide the basis for the complex system of channels, weirs and dams developed by the Gunditjmara in order to trap, store and harvest kooyang (short-finned eel — Anguilla australis). The highly productive aquaculture system provided an economic and social base for Gunditjmara society for six millennia. The Budj Bim Cultural Landscape is the result of a creational process narrated by the Gunditjmara as a deep time story, referring to the idea that they have always lived there. From an archaeological perspective, deep time represents a period of at least 32,000 years. The ongoing dynamic relationship of Gunditjmara and their land is nowadays carried by knowledge systems retained through oral transmission and continuity of cultural practice. [Source: UNESCO]

Over a period of at least 6,600 years the Gunditjmara created, manipulated and modified these local hydrological regimes and ecological systems. They utilised the abundant local volcanic rock to construct channels, weirs and dams and manage water flows in order to systematically trap, store and harvest kooyang (short-finned eel — Anguilla australis) and support enhancement of other food resources.

The highly productive aquaculture system provided a six millennia-long economic and social base for Gunditjmara society. This deep time interrelationship of Gunditjmara cultural and environmental systems is documented through present-day Gunditjmara cultural knowledge, practices, material culture, scientific research and historical documents. It is evidenced in the aquaculture system itself and in the interrelated geological, hydrological and ecological systems.

The Budj Bim Cultural Landscape is the result of a creational process narrated by the Gunditjmara as a deep time story. For the Gunditjmara, deep time refers to the idea that they have always been there. From an archaeological perspective, deep time refers to a period of at least 32,000 years that Aboriginal people have lived in the Budj Bim Cultural Landscape. The ongoing dynamic relationship of Gunditjmara and their land is nowadays carried by knowledge systems retained through oral transmission and continuity of cultural practice.

Importance of Budj Bim Cultural Landscape

The Budj Bim Cultural Landscape is important according because it bears an exceptional testimony to the cultural traditions, knowledge, practices and ingenuity of the Gunditjmara. The extensive networks and antiquity of the constructed and modified aquaculture system of the Budj Bim Cultural Landscape bears testimony to the Gunditjmara as engineers and kooyang fishers. Gunditjmara knowledge and practices have endured and continue to be passed down through their Elders and are recognisable across the wetlands of the Budj Bim Cultural Landscape in the form of ancient and elaborate systems of stone-walled kooyang husbandry (or aquaculture) facilities. Gunditjmara cultural traditions, including associated storytelling, dance and basket weaving, continue to be maintained by their collective multigenerational knowledge.

The continuing cultural landscape of the Budj Bim Cultural Landscape is an outstanding representative example of human interaction with the environment and testimony to the lives of the Gunditjmara. The Budj Bim Cultural Landscape was created by the Gunditjmara who purposefully harnessed the productive potential of the patchwork of wetlands on the Budj Bim lava flow. They achieved this by creating, modifying and maintaining an extensive hydrological engineering system that manipulated water flow in order to trap, store and harvest kooyang that migrate seasonally through the system. The key elements of this system are the interconnected clusters of constructed and modified water channels, weirs, dams, ponds and sinkholes in combination with the lava flow, water flow and ecology and life-cycle of kooyang. The Budj Bim Cultural Landscape exemplifies the dynamic ecological-cultural relationships evidenced in the Gunditjmara’s deliberate manipulation and management of the environment.

The Budj Bim Cultural Landscape incorporates intact and outstanding examples of the largest Gunditjmara aquaculture complexes and a representative selection of the most significant and best preserved smaller structures. These include complexes at Tae Rak (Lake Condah), Tyrendarra and Kurtonitj. Each complex includes all the physical elements of the system (that is, channels, weirs, dams and ponds) that demonstrate the operation of Gunditjmara aquaculture. The property also includes Budj Bim, a Gunditjmara Ancestral Being and volcano that is the source of the lava flow on which the aquaculture system is constructed.

Australian Aborigines — the ''World's First Astronomers''?

An Australian study has uncovered signs that the country's ancient Aborigines may have been the world's first stargazers, pre-dating Stonehenge and Egypt's pyramids by thousands of years. Professor Ray Norris said widespread and detailed knowledge of the stars had been passed down through the generations by Aborigines, whose history dates back tens of millennia, in traditional songs and stories. [Source: AFP, September 17, 2010]

"We know there's lots of stories about the sky: songs, legends, myths," Norris, an astronomer for Australia's science agency, the Commonwealth Scientific and Research Organization (CSIRO), told AFP. "We wondered how much further does it go than that. It turns out also people used the sky for navigation, time-keeping, to mark out the seasons, so it's very practical. People were nomadic so when Pleiades (the Seven Sisters star cluster) was up they would move to where the nuts and berries are. Another sign and it would be time to move to the rivers to fish for barramundi, and so on."

AFP reported: Norris, who has studied Aboriginal culture and historical accounts by white settlers, and made several trips to Arnhem Land in Australia's remote Outback, said his research also revealed more detailed astronomical thought. "Clearly some thinker in the past has been sitting down in the bush, watching an eclipse and trying to figure out how it works," he said, giving one example. Those thoughts are then encoded in the songs and ceremonies. If you take a lunar eclipse, the story in Arnhem Land is it's the Sun Woman and Moon Man making love, and when they make love the body of one covers the other."

Norris is now searching for evidence that would put a date on Aboriginal astronomy, such as a rock-carving of a meteor strike or comet. He is confident the Aborigines pre-dated European stargazers, including Britain's astronomy-linked Stonehenge, which is estimated at 3,100 BC, around the age of the Great Pyramid of Giza. "We've established there is all this astronomy, what I don't know is how far back this goes. If it goes back 10,000 or 20,000 years, that makes (Aborigines) the world's first astronomers," he said.

Ancient Aboriginal Tiger Shark Story

The Aboriginal Yanyuwa people believe Australia’s Gulf of Carpentaria was created by the tiger shark and developed a language that goes along with this belief. Georgina Kenyon of the BBC wrote: The tiger shark was having a really bad day. Other sharks and fish were picking on him and he was fed up. After fighting them, he met up with the hammerhead shark and some stingrays at Vanderlin Rocks in the waters of Australia’s Gulf of Carpentaria to speak of their woes before they set out to find their own places to call home. This forms one of the oldest stories in the world, the tiger shark dreaming. The ‘dreaming’ is what Aboriginal people call their more than 40,000-year-old history and mythology; in this case, the dreaming describes how the Gulf of Carpentaria and rivers were created by the tiger shark. The story has been passed down by word of mouth through generations of the Aboriginal Yanyuwa people, who call themselves ‘li-antha wirriyara’ or ‘people of the salt water’. [Source: Georgina Kenyon, BBC, May 1, 2018]

The tiger shark’s journey was challenging as he forged his way through the Gulf, creating the water holes and rivers in the landscape. He was turned away by many other angry animals who did not want him to live with them. A wallaby even hurled rocks at him when he asked if he could stay with her. But as he swam, the dreaming story explains, the shark helped create the waters of the Gulf of Carpentaria that we see today. “Tiger sharks are very important in our dreaming,” said Aboriginal elder Graham Friday, who is a sea ranger here and one of the few remaining speakers of Yanyuwa language. Some people here still believe the tiger shark is their ancestor.

The Yanyuwa traditionally fish these waters, catching and eating fish, turtle and dugong, but very rarely shark. Their heartlands lie over five main islands and more than 60 smaller, barren sandstone islets of the Sir Edward Pellew Group, which are scattered over 2,100 square kilometers. Vanderlin Island is the largest and furthest east, 32 kilometers from north to south and 13 kilometers wide.The 5.5-meter -long tiger shark, which travels over thousands of kilometres from these coastal waters to the Pacific Ocean each year, would have been a powerful mythological figure.

Part of Friday’s job as a sea ranger is to educate people in the old ways of hunting — that you only take what you need to eat from the waters. But just as importantly, he is helping teach young Yanyuwa their language and the cultural significance of sea animals. The rangers also maintain ceremonial sites and burial grounds on the islands as well as the ancient rock art, which, although very weathered, still shows images of sharks. “It makes sense to now have us, Aboriginal sea rangers, here to look after the seas; we know this country and how to fish sustainably,” Friday said. Up here in ‘saltwater country’, I often heard the expression that everybody looks north towards the Gulf, where the sharks would come in from. . The landscape here is flat, hot and sparse. To understand it you really need to understand the language and stories of its original owners. John Bradley, schoolteacher and linguist, wrote a book about the region and its people, “Singing Saltwater Country”.

Ancient Aboriginal Language Shaped by Sharks

The Aboriginal Yanyuwa people developed a language to go along with their belief about tiger sharks. In their ‘tiger shark language’, they have many words for the sea and shark. Georgina Kenyon of the BBC wrote: Yanyuwa is a beautiful, poetic language. Its rhythms sound like the sea it so perfectly describes. The language precisely expresses a sense of place, often describing complex natural phenomenon in a single word, showing how attuned the Aboriginal people are to nature. [Source: Georgina Kenyon, BBC, May 1, 2018]

“Yurrbunjurrbun” (“light beams shifting through water”) my guide Stephen told me, who is partly Aboriginal and has family in the Gulf. He knows some of the language and this region. As we sailed, passing clouds cast their shadows on the sea’s surface. “This is ‘narnu ngawurrwurra’ in Yanyuwa,” Stephen said, describing exactly what I was seeing. I repeated the words, feeling their weight and resonance.

What’s especially unusual about Yanyuwa is that it’s one of the few languages in the world where men and women speak different dialects. Only three women speak the women's dialect fluently now, and Friday is one of few males who still speaks the men’s. Aboriginal people in previous decades were forced to speak English, and now there are only a few elderly people left who remember the language.

Friday told me that the women in his family taught him to speak their tongue as a child. Then in early adolescence, he learned the men’s language from his male relatives. While women have a passive understanding of men’s language, they do not speak it, and vice versa for the men. No-one I spoke to could say why these different dialects originated. Perhaps it’s because men and women had different roles and spent little time together tens of thousands of years ago, or maybe it was a sign of respect to not speak another’s dialect.

But what is known is that the Yanyuwa language is intertwined with the animal. “Language brings about understanding of the shark. The five different words women and men have for shark shows how close a bond Yanyuwa have with the animal,” Friday said. Women’s words for the shark describe its nurturing side, as a bringer of food and life, while men’s words are more akin to ‘creator’ or ‘ancestor’. You could be punished if you didn't speak the right dialect at the right time. “See, there, to those rocks, if you broke the rules, you could be sent there!” Stephen said, as he gestured towards the barren Vanderlin Rocks.

I had a feeling he might have been adding a bit of drama to the situation, perhaps to stop me repeating his Yanyuwa words. But it’s true that the language’s beautiful tones belie the strictness surrounding its use. Men and women do not speak the other’s dialect as it shows disrespect in their culture or is considered rude. At the very least it sounds extremely odd if a man speaks the women’s dialect or vice versa.

But Yanyuwa does not stop at just dialects for men and women — there are yet more for ceremony and respectful language, too. There was also ‘signing language’, according to Bradley, useful for hunting when people needed to be quiet or sometimes to signal when travellers were entering a sacred place, but few people remember many sign words now. Children also learned ‘string language’ — tying straw or string together in specific patterns to represent sea creatures and food.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Australian Museum, National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2025