Home | Category: Aboriginals

NGAATJATJARRA

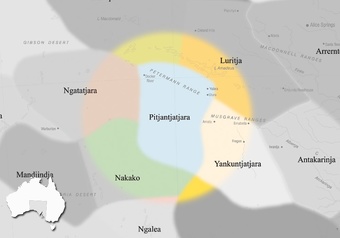

The Ngaatjatjarra are an Indigenous Australian people of Western Australia, with communities located in the north eastern part of the Goldfields-Esperance region. Also known as Ngatatjara Ngaayatjara, Ngadadjara, Pitjantjatjara and Western Desert Aboriginals, they speak the Warburton Ranges dialect of the Western Desert Language Group (Pitjantjatjara) in Western Australia and adjacent southwestern Northern Territory and northwestern South Australia. Their name for themselves, which means "those who have the word ngaata," which in turn means "middle distance," identifies the Warburton Ranges group in contrast with other, similarly identified dialect groups around them and does not imply any kind of tribal identity. [Source: Richard A. Gould, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

The population of Ngaanyatjarra people is estimated to be around 1,600 to 2,700, including those who those who reside permanently on Ngaanyatjarra Lands and those who visit the area. In the Ngaanyatjarra area of eastern Western Australia, approximately 2,000 to 2,300 Aboriginal people live across multiple communities, including some non-Ngaanyatjarra. The Ngaatjatjarra have traditionally been very mobile, which has made counting them difficult. Before the government resettled them in the late 1950s and early 1960s, many of these people followed a traditional nomadic hunting and gathering way of life, which dispersed them widely across the landscape. By 1970, the population at the Warburton Ranges Mission was around 400, and many Warburton people had moved elsewhere. |~|

The Pitjantjatjara language — to which the Ngaatjatjarra language or dialect belongs — is spoken in a wide area ranging from Kalgoorlie and Ceduna in Western Australia to the south and west, Ernabella and Musgrave Park in South Australia to the east, and Papunya and Areyonga in the Northern Territory to the north. Linguistic classifications currently accept Pitjantjatjara as part of the Wati subgroup of the Southwestern group of the Pama–Nyungan family, also called the Western Desert family. Most Ngaatjatjarra people are multilingual at the dialect level and often switch dialects when residing in new areas. The Western Desert linguistic family shares many features with other Aboriginal Australian languages.

The Warburton Ranges region is located at approximately 26° S and 127° E and includes rocky hills rising to an elevation of 700 meters (2,300 feet) above sea level and 300 meters (1,000 feet) above the surrounding terrain. Most of the surrounding area consists of sandhills, sand plains, and low laterite knolls. There is no permanent surface water, though relatively dependable water can be found by digging into dry creek beds and other specific locations. Weather records indicate that drought or semidrought conditions prevail in this region about half of the time, making it unsuitable for sustained European agriculture or pastoralism. ~

RELATED ARTICLES:

ABORIGINALS (FIRST NATION PEOPLE) OF AUSTRALIA: NAMES, DEMOGRAPHICS, LANGUAGES ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS IN WESTERN AUSTRALIA: SOME GROUPS, HISTORY, CUSTOMS, TRADITIONAL LIFE ioa.factsanddetails.com

MARTU OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA: HISTORY, CUSTOMS, TRADITIONAL LIFE ioa.factsanddetails.com

PINTUPI OF AUSTRALIA’S WESTERN DESERT: HISTORY, CUSTOMS, TRADITIONAL LIFE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS OF CENTRAL AUSTRALIA: SOME GROUPS, CUSTOMS, ART, LIFESTYLE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIANS IN NORTH NORTHERN TERRITORY: SOME GROUPS, CUSTOMS, LIFESTYLE ioa.factsanddetails.com

EARLY MODERN HUMANS IN AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

LIFE OF EARLIEST HUMANS IN AUSTRALIA: TOOLS, WEAPONS, ART, SETTLEMENTS ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINALS AT THE TIME EUROPEAN COLONIZATION BEGAN ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIA ABORIGINALS FROM 1900 TO PRESENT: DISCRIMINATION, ASSIMILATION, SOME RESTITUTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIA’S STOLEN GENERATIONS: VICTIMS, LAWS, RATIONALE, OUTRAGE ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL RELIGION: TRADITIONAL BELIEFS, DEMOGRAPHY AND DEATH ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL CUSTOMS, SOCIETY AND RITUALS ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL LIFE: WHERE THEY LIVE, WORK, DIET, HEALTH, ALCOHOL ioa.factsanddetails.com

TRADITIONAL ABORIGINAL LIFE: FOOD, HOMES, HUNTING ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL MEN AND WOMEN: GENDER, MARRIAGE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIAN SEX: PRACTICES, ATTITUDES, ADOLESCENCE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIAN ART ioa.factsanddetails.com

Ngaatjatjarra History

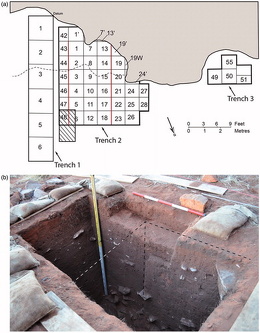

Puntutjarpa RockShelter, close to the Warburton Ranges, is a significant Australian archaeological site in the Western Desert where excavations in the late 1960s provided early evidence for human occupation in the Australian desert. The site, first excavated between 1967 and 1970, was initially thought to show a continuous occupation for the last 10,000 years. However, more recent analysis and dating have revealed three distinct phases of use over the last 12,000 years, mainly consisting of mid-Holocene deposits with thin layers of material from the last millennium and terminal Pleistocene. The site is named after the rock shelter, located in the Warburton Ranges of Western Australia, where it was excavated. [Source: Google AI]

The technology and lifestyle of Aboriginal people who used Puntutjarpa RockShelter, closely resembled those of the traditional Ngaatjatjarra at the time of European contact.Some changes were noted, such as a shift toward greater dependence on edible grass seeds and the addition of small, geometric, flaked stone artifacts to the toolkit. However, the economy remained oriented toward hunting and gathering the wild foods that still occur naturally in this area today. Recent archeological findings west of Alice Springs in the Northern Territory have revealed a 22,000-year-long sequence of Aboriginal occupation, suggesting that the ancient ancestors of present-day Western Desert Aboriginals may have exploited Pleistocene species that are now extinct. [Source: Richard A. Gould, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

European-Australian explorers first entered the region in 1873. However, permanent settlement based on a drilled well in the Warburton Ranges did not occur until 1934. This was followed by a period during which increasing numbers of nomadic desert people settled at the mission. Although the mission's population grew due to immigration, periodic epidemics periodically reduced the number of inhabitants. By 1970, the mission had become a government-supported settlement with a school, a clinic, and a small store, but it still lacked a self-sustaining economy. The Warburton population has remained dependent on outside support in the form of mission donations and government aid. However, resident Aboriginals are becoming increasingly involved in decisions about their community. There are also indications that the period of colonial dependency at Warburton and elsewhere in the region is ending, such as the movement of some Aboriginals to outstations during the 1970s.

Ngaatjatjarra Religion

The Ngaatjatjarra identify a variety of ancestral beings, primarily animals and other natural species, who performed creative acts during the Dreaming. These acts led to the present sacred geography. Patrilineages affiliated with these ancestors are responsible for instructing male initiates in these sacred traditions and maintaining sacred sites to increase the abundance of ancestral species. Dances and songs reenacting the myths of the Dreaming accompany these duties. [Source: Richard A. Gould, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

Traditionally, initiations occurred during periods of maximal social aggregation when local water and food resources were favorable. Novices were "saved up" for these occasions and initiated together. In more sedentary circumstances at the mission, novices are initiated when they are deemed old enough. As a result, ceremonies occur more frequently, but with fewer novices at any one time. Similarly, there is an increase in ceremonial activity at the mission and other settlements with regard to ceremonies involving the "increase" of the ancestral species. This increase occurs either by revisiting the sacred sites or, if they are too far away, by performing such ceremonies in absentia at the mission. |~|

Death and Afterlife According to the traditional belief, the soul divides into two parts after death. One part becomes a ghost that hovers around camp and serves as a sort of boogeyman to keep people, especially children, from wandering at night. The other part is the soul substance of an individual's ancestral Dreaming. After death, it is believed to return to the sacred Dreaming site and rejoin an undifferentiated pool of spirit ancestors. Later, it reemerges as part of the soul substance of another living person affiliated with that particular Dreaming. When someone dies, the campsite is altered to avoid the ghost, and the body is buried without ceremony. Later, when the group returns to the same area, the remains are reburied in a more elaborate ceremony. |~|

Ngaatjatjarra Marriage and Family Life

Traditionally, polygynous marriages were preferred, although monogamous marriages nowadays are more common. Residential rules favor patrilocality (living in the husband’s family home or community), but in actual cases residence is often determined by movement in response to drought and other local factors. There are strong obligations of avoidance and sharing behavior between in-laws of similar and different generations. However, divorce can occur by mutual consent and without formality. [Source: Richard A. Gould, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

Traditionally, people who habitually camped and slept together, mainly spouses and their offspring, have been considered a family and constitute the minimal social unit. Related family units sometimes group themselves in clusters within the overall campsite when conditions of rainfall and hunting permit. |~|

In regard to socialization, infants are closely nurtured until weaning. Afterwards, they rapidly assert their independence by forming playgroups with children of mixed ages. These groups sometimes establish temporary campsites and can travel cross-country, feeding themselves through foraging. Child-rearing is benign, and physical punishment is rare. In regard to inheritance, ceremonial and land-tenure group affiliations are patrilineal, meaning based on descent through the male line, but portable property is not important enough to warrant special inheritance rules. ~

Gender divisions were more sharply marked in ritual and sacred life than in daily subsistence. In the domestic sphere, women primarily gathered plant foods and hunted small game such as lizards and grubs, while men concentrated on large-game hunting. Women generally avoided handling hunting implements such as spears and spear throwers, but were central to food processing (e.g., seed grinding) and the collection and preparation of spinifex resin adhesives. Men, by contrast, typically engaged in stone artifact production and use. Exceptions were common in the desert context, and new patterns emerged after settlement near Europeans. By the 1960s, for example, women had begun hunting larger animals with the aid of trained dogs. Ritual activities, however, maintained strict gender boundaries: women were excluded from male ceremonies, and men from female rituals, although some ceremonies were performed jointly. Rules of ritual participation by sex were more rigidly defined and enforced than divisions of labor in daily subsistence.

Ngaatjatjarra Life and Culture

Prior to 1934, the Ngaatjatjarra were highly mobile and opportunistic in their settlement patterns. Following periods of sustained rain in particular parts of the desert, families gathered to take advantage of water and the game drawn to improved vegetation. These maximal groups could reach as many as 150 individuals, but they usually lasted only a few weeks before dwindling as local resources were depleted. Such gatherings were major social occasions, during which ceremonies, initiations, betrothals, and curing activities took place. [Source: Richard A. Gould, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

As drought conditions intensified, extended families dispersed to search for better hunting grounds, while smaller family units moved toward more reliable water sources. In cases of prolonged drought, families sometimes abandoned their home territories altogether and took temporary refuge with related groups as far as 500 kilometers away. Campsites could be revisited several times in a year or avoided for years at a stretch, depending on rainfall and resource availability. There were no strictly bounded territories, and social groups were flexible in size and composition. Minimal units, usually ten to fifteen related individuals, were commonly found foraging around dependable waterholes during droughts.

Domestic architecture was simple and adapted to the climate: conical or semicircular bough shelters in summer provided shade, while open-air camps with linear or semicircular windbreaks served in winter. Each family camp was centered on a hearth that functioned as the social focus, complemented by subsidiary hearths for warmth during sleep. In addition, there were specialized sites for tasks such as quarrying, hunting, woodworking, ceremonial activity, and rock art.

Healing practices combine the work of individual sorcerers with the use of herbal and common remedies. Illness and death are often interpreted as the result of hostile intent from others, sometimes from distant areas. Such cases may prompt a sorcerer’s inquest to determine the origin of the malevolent force and to carry out countersorcery against it.

In regard to the arts, Ngaatjatjarra ceremonial life has traditionally included decorative body painting, sacred paraphernalia, cave and rock painting, and a rich corpus of songs and oral narratives. Remarkably, the Ngaatjatjarra were among the few peoples worldwide who still engaged in cave and rock painting as a regular practice into the 1960s and 1970s. All forms of Ngaatjatjarra visual and oral expression emphasize shared cultural values and Dreaming beliefs rather than individual creativity. Today, Western Desert acrylic painting is flourishing in response to European-Australian demand, but Ngaatjatjarra participation remains relatively marginal.

Ngaatjatjarra Economic Activity

Prior to 1934, and among isolated or uncontacted groups thereafter, Ngaatjatjarra subsistence was based primarily on a limited range of edible wild plant foods. These were harvested in accordance with rainfall patterns and local geography rather than on a fixed annual cycle. On most days, women provided the bulk of the diet, consisting of plant staples and small animals, particularly lizards. Even before 1934, feral species introduced elsewhere by European-Australians—such as rabbits, feral cats, and, on occasion, camels and goats—had spread into the Western Desert and were incorporated into the Ngaatjatjarra diet. Men devoted considerable time and energy to hunting, though with relatively low returns. The main game sought included kangaroos, wallabies, and emus. Distribution of all foods—plant as well as animal—was governed by kin-based rules of sharing, ensuring an egalitarian allocation within the camp. [Source: Richard A. Gould, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

Traditional Ngaatjatjarra technology reflected the demands of mobility and employed three main strategies: 1) Multi-purpose tools, such as spear throwers, which doubled as fire-starters, mixing implements for tobacco and pigments, and percussion instruments for ceremonies; 2) Stationary appliances, such as heavy stone seed grinders, which were left in place at campsites for reuse whenever families returned; and 3) Instant tools, fashioned on the spot from available materials for immediate tasks. Despite their utilitarian function, spear throwers were often decorated with complex incised designs that served a map-like function, helping men and their families locate geographical landmarks.

Long-distance transport and exchange of materials and artifacts occurred widely across the Western Desert, largely within the context of ceremonial life. Exchanges typically took place between individuals with shared affiliations to ancestral beings and mythological tracks. These networks extended across vast areas, allowing the circulation of exotic items such as incised pearl shells from the northwest coast and sacred incised stones from central Australia. Such objects moved both between individuals and across patrilineages, reinforcing ceremonial and spiritual ties.

Ngaatjatjarra Kinship and Land Tenure

Patrilineal descent through the male line is an important principle in structuring group affiliation, especially to the patrilineages that claim descent from a common, mythical ancestor and to the specific places where that ancestor lived and performed important acts in the mythical past. Another dimension of Ngaatjatjarra social life is the dual division of kin into clearly defined groups, described by anthropologists as sections and subsections. These categories simplify expectations about marriage partners, food sharing, and access to resources. Among Aboriginal people who lived at Warburton Mission, Laverton, and other settlements such as Mount Margaret and Cosmo Newberry, kin were organized into four sections, which corresponded to a preference for first cross-cousin marriage.

With the coming together of families from different regions during the contact period, section terminology was modified to produce a hybrid “six-section” system, apparently unique to this area but structurally as symmetrical as the four-section model. By contrast, families arriving directly from the desert in the mid-1960s and early 1970s generally employed an eight-subsection system, associated with second cross-cousin marriage. These newly arrived groups at Warburton rapidly adapted their practices to the section system already in use by mission residents. [Source: Richard A. Gould, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

Kinship rules are classificatory in nature, extending terms used for close blood relatives (consanguines) to others of the same sex and generation. Such extensions carry behavioral expectations, defining with whom one may share food or resources, and who may be addressed directly or avoided, regardless of personal feelings toward that individual.

Land Tenure. Concepts of landholding are grounded in joint affiliation to sacred sites by corporate groups, primarily patrilineages whose members trace descent from a mythical ancestor. These ancestors are believed to have lived and traveled in the Dreaming (tjukurpa), and the places associated with their journeys are themselves known as tjukurpa. Such sites are sacred because they embody the spiritual presence of the ancestor. Tenure applies specifically to these sites, though the principle of trespass effectively extends control over the surrounding territory to the affiliated patrilineage.

Trespassing, whether deliberate or accidental, is a serious matter, and visitors must be shown the locations of sacred sites by local patrilineage members before entering unfamiliar country. Access is typically granted only to those who have established kinship ties, most often through marriage, with the local group. Today, this system of land tenure is under pressure from European-Australians whose relatively unrestricted movements, particularly for mining and development, often bring them into direct conflict with Aboriginal concepts of sacred geography. Debates over land claims and protection of sacred sites remain a central theme in Australian domestic politics.

Ngaatjatjarra Social and Political Organization

No corporate groups exist above the level of the patrilineage, and these function primarily in the sphere of sacred and ceremonial life. Within patrilineages, age and alternating generational divisions sometimes play a key role, particularly in the conduct of rituals. In daily affairs, Ngaatjatjarra society is highly egalitarian. Decisions involving multiple families are reached only after prolonged discussion, with participants often reluctant either to impose their will or to accept the decisions of others. In sacred matters, however, a more structured leadership emerges, based on relative age and depth of ritual knowledge. [Source: Richard A. Gould, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

Conflicts between individuals and families are not uncommon and may erupt into physical violence. Disputes frequently involve marriages and sexual relationships, though disagreements over the control of sacred sites and ritual knowledge also occur. Such disputes increased in frequency as European-Australian mining exploration expanded into the Western Desert from the 1960s onward.

Aggrieved individuals often mobilize kin to support them in disputes, and in serious cases retribution may take the form of spearing, directed at the thighs of male representatives of the offending kin group. There are no courts or centralized officials to resolve such conflicts. Sanctions are also applied at the level of patrilineages, particularly against trespassers or those committing sacrilege at sacred Dreaming sites under their guardianship. At the domestic level, informal mechanisms such as gossip play an important role in maintaining social control.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Culture Shock! Australia, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated October 2025