Home | Category: Aboriginals

ABORIGINAL MEN AND WOMEN

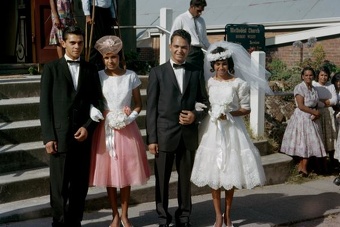

modern Cultural Union wedding ceremony ABC News

Aboriginal Men traditionally hunted, made tools, meted out justice and oversaw rituals that involved men. Women traditionally reared the children, gathered and prepared food and oversaw rituals that involved women. Aboriginal women have traditionally not been allowed to paint. In some clans, women make cat's cradle designs out of bark twine. They can make over 250 different designs including images of a lizard, a crocodile, a crab and a lightning bolt. Aboriginal women are also said to be good shots and they often the ones who do the hunting. [Source: "The First Australians" by Stephen Breeden and Belinda Wright, National Geographic February 1988]

Specific areas are designated for men’s rituals and women’s rituals, and women and men are excluded from each other’s sites. Physical punishment would be incurred if there was intrusion into the domain of the opposite gender; however, the depth of meaning associated with the rituals ensures that the power of suggestion preserves sanctity. Because both men and women have ritual do mains, there is a strong sense of propriety, and self-esteem is derived from this. While much ritual activity involves both sexes, mature men control both the ritual proceedings and the scheduling of activities.\^/

J. Williams Wrote in the “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life”: In traditional Aboriginal ritual and social life, male and female were sharply demarcated and differentiated. Any ritual that was sacred and secret to one gender was held out of eye and ear shot from the rest of the group. There are strict punishments for any females who transgress a male ritual. While the punishments were less extreme for men, they still avoid going near female rituals. In social life, gender and kinship also dictated behavior and decorum. There are precise rules that govern the interactions of men and women who are related to each other either by blood or marriage. To avoid contravening these rules, men and women tend to gather together in gender-exclusive groups when in public places. [Source: J. Williams, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life”, 2009, Encyclopedia.com]

Aboriginals have the highest rates of domestic violence in Australia. In some remote communities, Aboriginal women are 45 times more likely to suffer domestic violence than non-Aboriginal women. One Australian women said her country suffered from two evils, "chauvinism and alcohol consumption."

RELATED ARTICLES:

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIAN SEX: PRACTICES, ATTITUDES, ADOLESCENCE ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL CUSTOMS, SOCIETY AND RITUALS ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL LIFE: WHERE THEY LIVE, WORK, DIET, HEALTH, ALCOHOL ioa.factsanddetails.com

TRADITIONAL ABORIGINAL LIFE: FOOD, HOMES, HUNTING ioa.factsanddetails.com

LIFE OF EARLIEST HUMANS IN AUSTRALIA: TOOLS, WEAPONS, ART, SETTLEMENTS ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL RELIGION: TRADITIONAL BELIEFS, DEMOGRAPHY AND DEATH ioa.factsanddetails.com

RITUAL LIFE AND MYTHS OF ANCIENT AUSTRALIANS ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIAN ART ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS (FIRST NATION PEOPLE) OF AUSTRALIA: NAMES, DEMOGRAPHICS, LANGUAGES ioa.factsanddetails.com

EARLY MODERN HUMANS IN AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINALS AT THE TIME EUROPEAN COLONIZATION BEGAN ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIA ABORIGINALS FROM 1900 TO PRESENT: DISCRIMINATION, ASSIMILATION, SOME RESTITUTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIA’S STOLEN GENERATIONS: VICTIMS, LAWS, RATIONALE, OUTRAGE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS IN QUEENSLAND: SOME GROUPS, CUSTOMS, LIFESTYLES ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIANS IN NORTH NORTHERN TERRITORY: SOME GROUPS, CUSTOMS, LIFESTYLE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS OF CENTRAL AUSTRALIA: SOME GROUPS, CUSTOMS, ART, LIFESTYLE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS IN WESTERN AUSTRALIA: SOME GROUPS, HISTORY, CUSTOMS, TRADITIONAL LIFE ioa.factsanddetails.com

Aboriginal Gender Relationships

In traditional Aboriginal societies, there was a pervasive egalitarian ethos that placed every adult as the equal of others of the same sex. The operation of the kinship system exerted an overall balance in male-female relationships. Earlier ethnographers have tended to present Aboriginal culture as a traditional male-dominant, female-subordinate, hunting and gathering society. It has been argued, however, that this view is a narrow one generated through the androcentricity, and possibly the ethnocentricity, of the authors. Other authors have emphasized the complementary nature of gender roles, without conflict. [Source: Rosemary Coates, Ph.D.. Dr. Robert Tonkinson, Professor of Anthropology at the University of Western Australia International Encyclopedia of Sexuality, edited by Robert T. Francoeur, Continuum International Publishing Group, 2004, online at the Kinsey Institute \^/]

The complexity of the Aboriginal worldview and the concept of the Dreaming may have contributed to the differing perspectives of the ethnographers. The Dreaming, which contains the lore of creation and the permanence of the interrelationship of all things, is maintained through the different contributions to it made by women and men. Women’s narrative of the Dreaming deals with the rhythms of family life, while men’s narrative deals with the rhythms of the life of the whole group. Thus, there are male and female domains that are connected and complementary.

Gender difference is a significant aspect of Aboriginal symbolism, and consequently, there are gender-specific rituals. Many rituals relate to productive activities and utilize parallel symbols, for example, the woomera (throwing stick used by males when hunting) and the digging stick (used by females when gathering in sects). Certainly, men and women share a sense that both “men’s business” and “women’s business” are indispensable.\^/

J. Williams Wrote in the “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life”: Some Aboriginal languages encode gender grammatically through a system of noun classes. While somewhat similar to the use of gender in many Indo-European languages, the Aboriginal systems are more complex and have provided some interesting semantic relationships. For instance, in Dyirbal, which was once spoken in far northern Queensland, there were four noun classes. The first class included men and animate objects. The second class included women, water, fire, and violence; all of which were considered dangerous by the Dyirbal. The third class was composed of edible fruits and vegetables, while the fourth class included everything that was not in the first three classes. [Source: J. Williams, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life”, 2009, Encyclopedia.com]

For groups like the Mardu of Western Australia, the strong egalitarian nature of the society means that men and women feel equally able to make decisions and express opinions on most matters important to the well-being of the group. However, this does not mean that women and men have equal rights within Mardu society. For instance, women are not free to divorce their husbands, to have more than one husband at a time, or to engage in "husband-lending." Mardu men, on the other hand, are free to engage in the equivalent activities within the society. Older male relatives often make major decisions that will affect the lives of women, the most influential being infant betrothal. Infant betrothal is a social practice whereby an older male relative negotiates a husband for a baby girl, although the formal marriage does not take place until the girl attains puberty. The practice typically results in young girls being married to much older men.

Aboriginal Love, Courtship and Marriage

In traditional Aboriginal society, rules of kinship restricted sexual freedom and set the parameters for selection of spouses; however, premarital and extramarital sex was appropri ate. It is expected that every one marries. Marriage rules may give the impression that there was no room for the concept of “romantic love” in Aboriginal traditions. However, an insight into the nature of male-female sexual relationships may be obtained through some of the traditional myths, often expressed in song cycles. These include reference to affection, as well as physical satisfaction and mutual responsibility. The songs make explicit reference to circumcision rituals, to menstruation, semen, and to defloration. [Source: Rosemary Coates, Ph.D.. Dr. Robert Tonkinson, Professor of Anthropology at the University of Western Australia International Encyclopedia of Sexuality, edited by Robert T. Francoeur, Continuum International Publishing Group, 2004, online at the Kinsey Institute \^/]

One ritualistic means of courtship is reported through the Golbourn Island song cycles. In the songs, young girls engage in making figures out of string, the activity causing their breasts to undulate: This and the figures they make are designed to attract men. undulation of the buttocks was also used, along with facial gestures, that indicate a girl was willing to meet a boy in a designated area. These activities usually occurred around the time of menarche. Menstrual blood had an erotic appeal for men and some sacred myths allude to that theme. Menstrual blood was also seen as sacred, and, by extension, women were sacred during their menstrual period.\^/

Standards of beauty or attractiveness varied; however, obvious physical disabilities were seen to be a disadvantage and, similar to Western culture, youth is most highly valued. Infant betrothal was an important aspect of Aboriginal cultures and was often associated with men’s ritual activities, especially circumcision. In the Western desert region, for example, the main circumciser had to promise one of his daughters to the novice in compensation for having ritually “killed” him. Girls were often given to their husbands while still prepubertal, but coitus did not usually commence until her breasts had grown. In this context, girls may have had their first sexual experience by the age of 9 and boys by the age of 12.

Traditional Aboriginal Child Marriages

relaxed, outdoor wedding Polka Dot wedding

According to “Growing Up Sexually: “In traditional Aboriginal society marriages are significant to the forging of alliances, and often betrothal arrangements are made when the prospective bride is very young, or possibly even unborn. A man may not marry until he has undergone a significant part of the lengthy initiation process: thus, at marriage a man will be in his twenties or even thirties. Often a man’s first wife is the widow of an older man, and his subsequent wives may be much younger. A marriage may be signalled by the simple act of a couple living together and being accepted as married by their kin. It has been noted that the mere act of a woman walking through a camp to join a man at his request may constitute a marriage ritual. [Source: “Growing Up Sexually, Volume” I by D. F. Janssen, World Reference Atlas, 2004]

Inherent in the marriage system ruled by elders, older men had a monopoly on younger women and hd more polygamous relations. Elkin (1954) states that “infant betrothal is the normal thing; indeed a woman’s daughter is promised to a man or the latter’s son or nephew before she is born”. “Among Yuwaaliyaay people...infant betrothal appears to have been the norm”. Among the Aboriginals of the Wheelman tribe a baby girl is betrothed to a youth or man; he “grows” her, or supports her growing up (Hassell, 1936). Parker notes on the Euahlayi tribe:

“At whatever age a girl may be betrothed to a man. “There is often a baby betrothal called Bahnmul”] he never claims her while she is yet Mullerhgun, or child girl; not until she is Wirreebeeun, or woman girl”. Calvert mentions that ... a female child is betrothed, in her infancy, to some native of another family, necessarily very many years older than herself. He watches over her jealously, and she goes to live with him as soon as she feels inclined”. Spencer and Giller also mention betrothal of Aranda girls “many years before the is born”. Radcliffe-Brown (1913) that “marriages are arranged before children are born”. Provis writes in Taplin of the Streaky Bay South Aboriginals that there can sometimes be seen “the incongruous spectacle of a little child betrothed to a grown man. The girl is called his Kur-det-thi (future wife). They sleep together, but no sexual intercourse takes place till the girl arrives at the age of puberty”. Schürmann writes in Woods (1879) of the Port Lincoln tribe that “long before a young girl arrives at maturity, she is affianced by her parents, to some friend of theirs, no matter whether young or old, married or single”.

Howitt (1904) for the Wolgal tribe reports that “a girl is promised as a mere child to some man of the proper class, he being then perhaps middle aged or even old”. Betrothal occurred when “quite young”, states Bonney (1884). Thomson (1933) remarked: “There is in this society nothing approaching the sexual licence that Professor Malinowski found to be the regular thing before marriage in the Trobriands. In the Koko Ya’o tribe a girl has normally no sexual experience before marriage, for she is married actually before puberty, even before she is physiologically capable of bearing children. Prior to this she lives at her parent’s fireside, and even during the day she is under the constant surveillance of her mother, whom she accompanies in her daily quest for food. The reason that the natives give for this child-marriage is that the girl will not be afraid of her husband if she grows up with him”. According to the ideal of the past, by this time [adolescence] a girl should be securely ensconced in her marital household with a man she had been promised to from infancy if not before she was born. In 1981, however, this ideal was realised by no one” (Burbank).

Aboriginal Marriage in the 1800s

George P. Monger wrote in “Marriage Customs of the World From Henna to Honeymoons”: “Aborigines (Australian) Western writers have written that there seems to have been little, if any, ceremony in the aboriginal method of marrying. Westermarck (1894) wrote: “In Australia, wedding ceremonies are unknown in most tribes, but it is said that in some there are a few unim- portant ones.” The Kaurna aboriginal group from South Australia provides a model of Australian aboriginal society and mores and demonstrates that Westermarck’s remarks above were simplistic and based based on a misunderstanding of the society from 19th-century European and white Christian moral viewpoint. [Source: “Marriage Customs of the World From Henna to Honeymoons”: “ by George P. Monger, 2004 ^]

Westermarck quoted Fison and Howitt, writing of the Kaurna in 1880, who said that marriages were brought about “most frequently by elopement, less frequently by captures, and least frequently by exchange or by gift.” In Kaurna society, marriage was not seen as a barrier to sexual relations, and sexual intercourse with a member of the family group was offered as a part of hospitality. Adultery was not a concept recognized or understood by the Kaurna, and indeed it was common for a woman to have sexual relations with a number of men with the full approval and encouragement of her spouse. To the British settlers, this exemplified the low moral standards of the Aboriginals.

Anthropologists have described practices of central Australian Aboriginals where the bride’s hymen was artificially perforated. The assisting men, in a stated order, then have intercourse with the woman. We find records of similar practices where a group of men have sexual access to the bride for the period of the wedding ceremonial. Elopement could be an issue. An eloping couple had to stay away for many years or they would be punished and any children killed. They could rejoin their families only after several years and with gifts of food for the man’s parents.

Aboriginal Marriage Arrangement in the 1800s

George P. Monger wrote in “Marriage Customs of the World From Henna to Honeymoons”: Ceremonial activity did occur between the families, and accounts in some of the anthropological and popular writings are missing the social subtleties. It was usual and expected that the young woman would marry into a different family group to ensure an increase in the gene pool; it was very rare for the couple to know each other before the wedding. Aboriginal groups usually identified with certain totem groups, and there were rules about which totem groups could intermarry. [Source: “Marriage Customs of the World From Henna to Honeymoons”: “ by George P. Monger, 2004 ^]

Arrangements and negotiations did not begin until the parents were sure that the girl would survive to marriageable age. Two groups, one from each of the yerta, would meet together to discuss the arrangements to transfer the woman from her family group to that of her spouse. Polygamy was allowed in aboriginal society, usually polygyny (multiple wives) and sometimes polyandry (multiple husbands), although, as mentioned above, the woman was not expected or required to reserve her sexual favors for only her husband (similarly the man was not expected to be faithful to one woman or to his harem). The groom’s family group camped near the bride’s group for about two days and through a series of rituals established that they were gathered for a marriage. During this time the groom’s family sent an emissary to the bride’s group to negotiate the marriage transaction, discussing the relationships and settlements in great detail.

Once agreements had been achieved, each of the negotiators returned to their family group to announce that the marriage could take place. The actual marriage occurred at daybreak following the completion of the negotiations. Usually the bride’s brother would hand her to her new husband, although occasionally this was done by her father. She would immediately begin to live and work with her new family group. Her new life was more difficult if she joined a harem—as the older harem members would sometimes give her a hard time—and easier for her if she entered a monogamous marriage.

In some groups, before a young man was able to make a choice of bride, the parents of the eligible girls would stand around him and beat him; he would not retaliate, but would not speak to any of them again, not even to the parents of the one he chose. He indicated his choice by presenting the parents with food, and, if the girl agreed, he led her away from her family group. There were instances of couples falling in love and eloping. The couple would have to ensure that they eloped to an area well away from their family routes. If they were caught he would be injured with a spear through his thigh, and the girl would be hit on the head with a club. Any offspring resulting would be killed. If they kept away for some years, they could eventually rejoin their family group by taking a gift of food to the young man’s parents. The white settler population did not recognize the validity of aboriginal marriage— marriages were to be conducted under English law—and the clergy disapproved of marriage between the natives and the settler population. The Anglican bishop of Adelaide had forbidden such marriages; consequently those mixed marriages that did occur had to take place in a civil ceremony.

Aboriginal Wife-Stealing in the 1800s

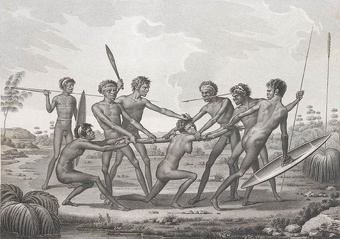

George P. Monger wrote in “Marriage Customs of the World From Henna to Honeymoons”: “Wife-stealing (milla mangkondi) was prevalent among aboriginal groups, but this did cause great acrimony among community groups. However, all indulged in the practice as it was seen as a method of increasing the gene pool. All tribal groups had a great antipathy toward wife-stealing, and the worst affront that could be dealt to a group was for a young wife to be stolen from an elder. The writer went on to describe the stealing of a wife at night, the man using his spear to ensnare the woman’s hair and draw her from her group, and the subsequent ordeal to prevent fighting between the family groups in defense of the young woman and young man.

It was with the onset of puberty that an aboriginal girl became a woman, able to join the group of marriageable women and take part in the family hospitality laws. This usually happened around the age of ten or twelve years, and she was expected to join her promised spouse soon afterward. However, no man married before the age of about twenty-five, after he had passed through his initiation into manhood; indeed, it was more advantageous for a girl to marry an older man who commanded higher food distribution rights. However, younger men were not barred from having sexual relations with the wives of the older men. The belief was that the sex act was a gift of the gods and that people should enjoy it at their discretion. [Source: “Marriage Customs of the World From Henna to Honeymoons”: “ by George P. Monger, 2004 ^]

“An anonymous correspondent to the Chambers Journal of 22 October 1864 described how the Aboriginals of Australia obtained a wife. The writer begins by noting that women were considered much inferior to men and had to carry their belongings from one camp to the next as beasts of burden. Courtship was apparently unknown to them, so that if a young warrior wished a wife, he exchanged a sister or other female relative for the woman. However, if there was no woman among his tribe who interested him, he might take one from some other encampment by stunning her with his war club and dragging her insensible body to some secluded spot. When she recovered, he took her back to his tribe’s encampment in some triumph. Sometimes two young men would work together, spending time to spy on the movements of the women who interested them. When they had made their decision, they would creep naked toward the campfire around which the women slept, carrying only their “jag-spears.” When they got close enough, the man would wind his spear in the woman’s hair to entangle it in the barb point; she would be roused from her sleep with a jerk from the spear in her hair, to find another spear point at her throat. She could then be led away because she was aware that if she made any attempt to escape she might be killed.

Once she had been secured in a place away from the camp, the young men would return for another young woman. If alarm was given, the prospective abductors would escape to try again another day. The account continues by telling us that a distinguished warrior who had carried off a wife might volunteer to undergo “the trial of spears” to prevent the two tribes having to go to war over the incident. The two tribes would meet, and ten of the young men from the woman’s tribe would be given three reed spears and a throwing stick each; the young warrior, armed only with a bark shield (about eighteen inches by six inches), would stand about forty yards away from the men, who, on a signal, would throw the spears at him in rapid succession, which the young warrior had to parry with the shield. Having passed this test (as was usual, because of tribal skill in using the shield) and consequently atoning for the abduction, the two tribes would conclude the event by feasting together.

However, Westermarck (1894) stated that where marriage by capture is said to take place between hostile tribes in Australia, “we are aware of no tribe—exogamous or endogamous—living in a state of absolute isolation.” He went on: “On the contrary, every tribe entertains constant relations, for the most part amicable, with one, two or more tribes; and marriages between their members are the rule. Moreover, the custom, prevalent among many savage tribes, of a husband taking up his abode in his wife’s family seems to have arisen very early in man’s history. . . . there are in different parts of the world twelve or thirteen well-marked exogamous peoples among whom this habit occurs.” In many wedding practices there is an apparent conflict between the bride’s party and the bridegroom’s party and a show of reluctance on the part of the bride to be taken in marriage. This is understandable in the case of arranged marriages where the couple has little say in the choice of partner. However, shows of reluctance are commonly seen in situations where the two have either given consent or made a free choice.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Culture Shock! Australia, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated September 2025