Home | Category: Aboriginals

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL CUSTOMS

In the old days each Aboriginal had a place around the campfire. When the father returned from a day of hunting the family spent the evening and night making up dances about what happened to them. All the food that was caught was shared among everyone in the community and selfishness was considered the cardinal sin. On Aboriginal sentiments, travel writer Paul Theroux wrote: "They had no word for love, friendship was everything, the strongest bond in the world. Marriage was regarded as a bond of friendship not love." Lutheran Aboriginals said "Jesus is my best friend" rather than "I love Jesus."

Australian Aboriginal etiquette emphasizes deep listening respect for Elders, and honoring Country through acknowledgments, respecting gender-specific roles, and understanding the importance of kinship and collective sharing within communities. When engaging with Aboriginal people, be mindful of potential sensitivities around names of deceased relatives and sacred knowledge.

Aboriginals don't make eye contact. Avoiding eye contact is a sign of respect. Aboriginals often have a rather limb hand shake. The Murngin Aboriginals of Arnhem Land treat old people as if they were dead when they get sick. The groups gives them their last rites and often the old people became sicker and died.

Aboriginal people comment that non-Aboriginal people say "thank you" all the time. Aboriginal social organization is based on a set of reciprocal obligations between individuals that are related by blood or marriage. Such reciprocal obligations do not require any thanks: If I am related to you and you ask me to share my food with you, I am obligated to do so without any expectation of gratitude on your part. Anglo-Australians often misconstrue this behavior as rude.

RELATED ARTICLES:

ABORIGINAL LIFE: WHERE THEY LIVE, WORK, DIET, HEALTH, ALCOHOL ioa.factsanddetails.com

TRADITIONAL ABORIGINAL LIFE: FOOD, HOMES, HUNTING ioa.factsanddetails.com

LIFE OF EARLIEST HUMANS IN AUSTRALIA: TOOLS, WEAPONS, ART, SETTLEMENTS ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL MEN AND WOMEN: GENDER, MARRIAGE, SEX ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIAN SEX: PRACTICES, ATTITUDES, ADOLESCENCE ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL RELIGION: TRADITIONAL BELIEFS, DEMOGRAPHY AND DEATH ioa.factsanddetails.com

RITUAL LIFE AND MYTHS OF ANCIENT AUSTRALIANS ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIAN ART ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS (FIRST NATION PEOPLE) OF AUSTRALIA: NAMES, DEMOGRAPHICS, LANGUAGES ioa.factsanddetails.com

EARLY MODERN HUMANS IN AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINALS AT THE TIME EUROPEAN COLONIZATION BEGAN ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIA ABORIGINALS FROM 1900 TO PRESENT: DISCRIMINATION, ASSIMILATION, SOME RESTITUTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIA’S STOLEN GENERATIONS: VICTIMS, LAWS, RATIONALE, OUTRAGE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS IN QUEENSLAND: SOME GROUPS, CUSTOMS, LIFESTYLES ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIANS IN NORTH NORTHERN TERRITORY: SOME GROUPS, CUSTOMS, LIFESTYLE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS OF CENTRAL AUSTRALIA: SOME GROUPS, CUSTOMS, ART, LIFESTYLE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS IN WESTERN AUSTRALIA: SOME GROUPS, HISTORY, CUSTOMS, TRADITIONAL LIFE ioa.factsanddetails.com

Aboriginal Society

At the time that Europeans arrived in Australia, Aboriginals were essentially semi-nomadic hunter-gatherers who lived in tribes made of extended family groups or clans, with clan members believed to have descended from a common ancestral beings. Tribal and clan bonds remain strong today. Some old Aboriginals in the 1990s didn't know their birthday or the year they were born and can remember relatives using stone axes to split wood.

Aboriginal traditions are complex and varied. There are elements of the culture that are the exclusive province of certain individuals or groups and are not permitted to be revealed to others. The concept of the Dreaming is of fundamental importance to Aboriginal culture and embraces the creative past—where ancestral beings instituted the society—the present, and the future. The Aboriginal worldview integrates human, spiritual, and natural elements as parts of the whole and is expressed through rituals. [Source: Rosemary Coates, Ph.D.. Dr. Robert Tonkinson, Professor of Anthropology at the University of Western Australia, International Encyclopedia of Sexuality, edited by Robert T. Francoeur, Continuum International Publishing Group, 2004, online at the Kinsey Institute \^/]

Culture and wisdom have traditionally been passed on through the community’s rich repertoire of oral history, stories and songs — there was no writing — culminating in the formal, and often painful, initiation ceremony for children passing into adulthood. Secret knowledge of sacred things was communicated at this ceremony. Men and women have segregated secrets — ‘men’s business’ and ‘women’s business’. To this day, there are many such secrets still carefully kept from the uninitiated.

Many of the most important and sacred rituals for Aboriginals are secret and performed mostly by men. In traditional Aboriginal societies revealing the secrets to outsiders or women could result in harsh punishment. In the past a death sentence — sometimes being ‘sung to death’ — was not uncommon for transgression of tribal laws. In some areas trials-by-spear were sometimes held in the 1970s in which a person accused of revealing secrets was surrounded by a circle of spear-wielding clansmen who aimed at his thigh. There are many stories of singing-victims falling down dead. It has been said that the Aboriginal system of justice was harsh, but was effectively and fairly meted out by the elders of the tribe. [Source: "Arnhem Land Aboriginals Cling to Dreamtime" by Clive Scollay, National Geographic, November 1980]

Aboriginal Kinship and Family

Ilsa Sharp wrote in “CultureShock! Australia”: Kinship and extended family are central to Aboriginal integrity. That is why an Aboriginal house with capacity for a family of five may well be crammed to bursting point with 50 or more, just because the ‘rellies’ dropped by for a while on their latest walkabout, often in connection with a family funeral. An Aboriginal never refuses family as a house guest, no matter how absurd the numbers or how difficult the resulting overcrowding. Just another sticking point with white neighbours. [Source: Ilsa Sharp, “CultureShock! A Survival Guide to Customs and Etiquette: Australia”, Marshall Cavendish, 2009]

While the basic social unit is the family, there is a complex system of classificatory kinship that dictates marriage rules. Kinship status imposes responsibilities and behaviors toward other kin. A basic feature of the kinship system is that the siblings of the same sex are classed as equivalent, so that, for example, the sisters of a child’s mother would all be classed as “mother.” The children of one’s parents’ siblings would, there fore, be classed as “brothers” and “sisters.” Through this system, kinship may be extended to include people who do not have a blood relationship. [Source: Rosemary Coates, Ph.D.. Dr. Robert Tonkinson, Professor of Anthropology at the University of Western Australia International Encyclopedia of Sexuality, edited by Robert T. Francoeur, Continuum International Publishing Group, 2004, online at the Kinsey Institute \^/]

The moiety system of social classification — in which a society is divided into two complementary halves, or moieties, often for kinship and marriage purposes — provides correct intermarrying categories, Although it does not determine marriage partners. Within moieties, there are groupings which, for want of a better word, have been classified as “clans”, although a more accurate translation of the words used by the people themselves might be “crowd” or “lot.” A clan is usually identified by an association with a natural species, for example, the barramundic clans (named after a species of fish), or Eaglehawk. Each clan has a dialect and each person is a member of one linked dialect-clan pair, which is that of her or his father. This categorization has significance in all aspects of social activity and includes specific mythic and ritual knowledge and beliefs. The clan indicates territorial possession as well as belief system. Membership of the dialect-clan group defines a person’s social position, as well as their belief system.\^/

J. Williams wrote in the “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life”: Behavior and interpersonal relations among Australian Aboriginals are defined by who one is related to and who one is descended from. In many Aboriginal societies, certain kinfolk stand in avoidance relationships with each other. For instance, in some groups a son-in-law must avoid his mother-in-law completely. Individuals will often change course entirely and go out of their way to avoid a prohibited in-law. In these complete avoidance relationships, he must not have any contact with her at all. In other types of relationships, a son-in-law can only speak to his mother-in-law by way of a special language, called "mother-in-law language." The opposite of avoidance relationships are joking relationships. These are relationships between potential spouses that typically involve joking about sexual topics. [Source: J. Williams, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life”, 2009, Encyclopedia.com]

Play Among Aboriginal Children

According to “Growing Up Sexually: The Ooldea aboriginals believe that the ‘didji’pulka (age three or four to the beginning of puberty) has no sexual desires. Among Central Australians, boys and girls may not before puberty eat large lizard for if they do so they will acquire an abnormal craving for sexual intercourse. However, latency is nonexistent: “Small children play in the bush away from the main camp. Although it is collective play, there is the tendency to choose partners after a time and to depart in pairs to the secrecy of the bushes”...Bands of children wander on the sand-hills, often indulging in erotic play during such games as “father and mother” ”. The play may even reveal adult secrets: “Coitus a tergo was denied, yet it undoubtedly occurred as shown by the behavior of the children during the play hours” (Róheim, 1958). [Source: “Growing Up Sexually, Volume” I by D. F. Janssen, World Reference Atlas, 2004]

The crossing of sexual (copulatory) themes and child actors appears in Aboriginal mythology. The children also seem to participate in coitomimic behaviours as performed in mock rituals. Schidlof (1908) noted childhood participation in such dances, in which ... during the Meke-Meke dance, outside the circle of the adults, several small boys stood opposite each other in pairs, embraced each other, and made obscene movements to the beat of the music, which left nothing to be desired in terms of clarity. The parents present laughed and screamed with joy, especially the women, who were extremely amused by the behavior of their six-year-old offspring”.

Some later sources include Tonkinson (1978): “For the first half-dozen or so years of their lives, the children usually play in mixed-sex groups and their games sometimes include “making camp” and “mothers and fathers”. This at times includes attempts at sexual intercourse, and the staging of adultery, elopement, and so on. This amuses adults, who turn a blind eye to such erotic play, although an older relative may mildly scold them if the couple concerned stands in an “incestuous” relationship, as a reminder about the correct behaviors they will have to observe as adulthood approaches”. Pilling (1992) mentioned “intercrural sexual stimulation” by two five-year-old boys, and masturbation of a dog by an eleven-year-old. Boyer et al. (1990) stated that “[a]lthough adult homosexuality is denied, many games involve heterosexual and homosexual cohabitation” in young Pitjatjatjara children. Coates (1997) mentions anecdotal “sexual rehearsal play” when talking about the nonindigenous population, and deems it as common as anywhere. However, aboriginal “[g]irls were often given to their husbands while still prepubertal, but coitus did not usually commence until her breasts had grown. In this context, girls may have had their first sexual experience by the age of 9 and boys by the age of 12”.

Aboriginal Festivals and Celebrations

Traditional Aboriginal ceremonies are still held in many parts of Australia. They are often held in special Dream Places with links to ancestral beings. Some places are regarded as dangerous and entrance is restricted by Aboriginal law. Aboriginals have traditionally not made a big deal about birthdays. In the past they often didn't even know when their birthdays was or how old they were. Aboriginals refer to the time before white men arrived as "Before Trousers."

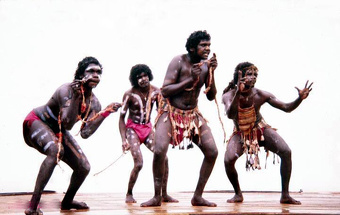

Corroborees are sacred meetings and ceremonial and festive gathering of Aboriginal clans featuring music and dancing. For thousands of centuries Aboriginals from different clans and groups used to gathered for corroborees in which participants would sing, dance and pass their knowledge of dream time to the next generation. The Sydney Opera house was built on a corroboree site. Aboriginals also used to hold corroborees at 7,131-foot-high Mount Kosciusko—Australia's highest mountain—and feast on bugong moths.

Welcome to Country Ceremonies are a rituals performed by Aboriginal traditional owners welcome people to their Ancestral land (Country) at an event, showing respect for their ongoing connection to the land. This formal practice often includes a speech, dance, song, or smoking ceremony (See Below), and is performed by a local Elder or representative to give their blessing and acknowledge the community. Welcome to Country ceremonies are part of reconciliation as they acknowledge the traditional ownership of the land and involve Aboriginal Australians in events that take place on their land. Smoking ceremonies are performed by Indigenous elders and community members in an event open to the non-Indigenous Australian public, as opposed to closed ceremonies performed within a community. Traditionally, smoke and fire have been used by Indigenous Australians as a form of communication. Individuals light a fire when entering another group's country, signalling their entry to the people who live there, and acting as a call for help when necessary.

Aboriginal Smoking Ceremonies

Smoking ceremonies are ancient and contemporary events held among some Aboriginal Australians that involves smouldering native plants to produce smoke. This herbal smoke is believed to have both spiritual and physical cleansing properties, as well as the ability to ward off bad spirits. In traditional, spiritual culture, smoking ceremonies have been performed following either childbirth or initiation rites involving circumcision. In the 21st century, smoking ceremonies have become a more frequent occurrence as part of Welcome to Country ceremonies. [Source: Wikipedia]

Research has shown that heating the leaves of Eremophila longifolia (commonly known as the Berrigan emu bush), one of the plants used in smoking ceremony, produces a smoke with significant antimicrobial effects. These effects are not observed in the leaves prior to heating. Fumigating a newborn infant, a mother who has just given birth, or a boy who has just been circumcised, is considered to assist in preventing infection.

Smoking ceremonies are done at key milestones throughout one's life, depending on the traditions of each Indigenous nation. Smoke may also be created by lighting a fire of paperbark, then smouldering green leaves atop the flame. The fire may be created in a pit in the ground, in the area itself or in a bucket. If it occurs in an enclosed space, the practice itself is altered slightly. A small fire may be built within the home, or a bucket of smoking coals may be brought into the house.

During their 2018 royal visit of Australia, Fiji, Tonga and New Zealand, the Duke and Duchess of Sussex participated in a smoking ceremony to commemorate the unveiling of the Queens Commonwealth Canopy in K’Gari National Park. Butchulla elders performed the ceremony as a Welcome to Country, highlighting the focus on Indigenous forests encouraged by the Queen's Commonwealth Canopy program. It was the first smoking ceremony performed for royalty.

Aboriginal Rites for Infants

In a traditional rite for infants, an Aboriginal mother squirts milk from her here breast into a fire fed by wood from the Kungaberry tree. Here child is then passed through the smoke in a ritual of purification and communion with the Dreamtime ancestors.

On Aboriginal man told National Geographic, "I was born under that tree, that coconut palm. And when I was born, my mother took the placenta, wrapped it wax and buried it here."

Smoking ceremonies may be performed at birth to welcome a newborn into the community and ensure that the mother and child will both be healthy throughout their lives. It is considered ‘baby business’ and is thus the responsibility of women in the community. Aspects of the practice have specific sacred meanings. In the Darug nation, smoking the feet represents a connection to country; the chest represents the connection between heart, family and country; the hands the spiritual imperative to take only what's needed from the land; and the mouth the Indigenous language.

Aboriginal Initiation Rituals

Initiation is an important part of Aboriginal life. Not everyone is initiated and in most cases the proceeding are secret. Most are associated with men. Women have their own secret ceremonies. Initiation rituals mark the passage of a child into adulthood. Exclusion of young males — in which they live in the bush for som period of time — is an important part of the initiation process. These days school schedules are taken into consideration. [Source: J. Williams, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life”, 2009, Encyclopedia.com]

Male initiations are still practiced by the Aranda in central Australia and circumcision is an important part of this initiation. Circumcision or subincision on boys is a way of welcoming them into adulthood, marking the beginning of their involvement with men's business. subincision is a procedure where the underside of the penile urethra is incised, primarily documented among certain Australian Aboriginal groups. Smoking ceremonies are part of the initiation ceremony, encouraging both spiritual and physical cleansing. Smoking leaves of the emu bush serves a dual purpose of cleansing one's spirit to connect them to their country and sterilising instruments used in the circumcision itself.

Journalist Clive Scollay observed a circumcision ceremony performed on 10 year old boys in Arnhem Land in 1980. Each mornings during the 10 day period preceding the circumcision the boys were painted with white clay which symbolized male potency. Drawn on top of their whitewashed bodies were patterns and symbols similar to those on rock and bark paintings. After the painting was over there was a lot of jumping up-and-down, dancing and didgeridoo music. During the circumcision itself good fortune came to the families of the boys who didn't cry out while screams brought dishonor. After the ritual the initiates spent weeks in the bush with their uncles learning the sacrad law.[Source: "Arnhem Land Aboriginals Cling to Dreamtime" by Clive Scollay, National Geographic, November 1980]

See Circumcision and Defloration Under AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL CUSTOMS, SOCIETY AND RITUALS ioa.factsanddetails.com

Aboriginal Ties to Their Land

Ilsa Sharp wrote in “CultureShock! Australia”: The Land Mother Land rights are central to Aboriginality. It is hard for outsiders to comprehend the very deep and mystic way in which Aboriginals feel they are bound to the land. This is not the feeling of the white farmer who loves his land through proud possession and control of it. Rather, the Aboriginals feel they are owned and controlled by the land. The earth is their ‘mother’. In a far-off ‘Dreamtime’, believe the Aboriginals, ancestral spirits, beings and other agents of Mother Earth travelled across the land creating people, places, plants and animals. You will hear a lot in Australia about Aboriginal ‘sacred sites’. [Source: Ilsa Sharp, “CultureShock! A Survival Guide to Customs and Etiquette: Australia”, Marshall Cavendish, 2009]

Once a place is declared a sacred site, it becomes extremely problematic to develop it or tamper with it in any way. A pitched battle went on for many years now over State Government development proposals for a riverside site in Perth, Western Australia, formerly a brewery, for exactly this reason (but it is now an upmarket apartment complex). The sacred sites were the halting points where the ancestral beings paused on their journeys across the land. There are many other such cases across the country.

Each Aboriginal’s very identity, and position within the tribe or clan, is based on the place where he or she was born, and is linked to an ancestral being, expressed through a plant or an animal. The soil is the source of all life, and the home to which all life returns after death, for recycling into life again. There is no sense of separation from other lifeforms. The Aboriginals lived in complete harmony and balance with the wild land. Their burning-back patterns were an essential part of the ecosystem, regenerating and benefiting many species of plants and animals in an ecology geared for natural fires. They took from the land only what they needed to survive.

Aboriginals in White Society

Aboriginal communities are for the most part separated from white communities. It is unusual to see Aboriginals in the business districts of Sydney, Melbourne or Perth. It is equally rare to see whites in Aboriginal areas. Even in towns where Aboriginals make up 15 percent of the population, they are rarely seen working in shops and offices. Many rely on welfare and unemployment for income. One Aboriginal woman said: "The whites in power broke our cultural cycle...So we've drifted along. Among ourselves we call this the last generation.”

Despair seems to be a component of being an Aboriginal in the modern world. Some of it os the result of being dehumanized by whites. Robert Tickner, the former federal Aboriginal-affairs minister told Newsweek, "I couldn't be an Aboriginal in Western Australia. Either I'd be a chronic alcoholic or I would have killed myself. I mean, people are put down in the most vicious way."

Aboriginals that live in urban areas have adapted to the modern world in various ways. Those who live in rural areas have kept many of the old ways. They may still speak their Aboriginal language or creolized version of it. and still eat traditional foods and use traditional medicines and retain the knowledge of where to find them and how to prepare them.

Young Aboriginals have been losing interest in the old ways for some time. In the 1980s, less than a dozen Gagudju elders remained who carry on the old ways, which included rock painting, telling of dreamtime stories and corroboree, a ceremonial dance that honors the "dreamtime" creators and kicks up a lot of dust. The elders said they learned the lessons from their elder under the threat of getting speared if they didn't sit quietly and listen. [Source: "The First Australians" by Stephen Breeden and Belinda Wright, National Geographic February 1988]

Racism Towards Aboriginals in Australia

Aboriginals have been called "Abos," "boongs," "bings" and "murkies" by whites. Aboriginal women were sometimes refereed to as a "gins." A "gin jockey" was a white man who married an Aboriginal women to gain access to her weekly welfare check. A "gin burglar" was term from the old days describing an Aboriginal woman kidnapped for sexual purposes. "Creamies" and "halfies" were the most sought after Aboriginal women.∝

Many Australians complain there are too many Aboriginals. Foreigners who visit Australia wonder how this can be when they stay in Australia for two or three weeks without seeing any. White Australians often complain that Aboriginals never fix anything and if something is lost they don't get a new one. According to Theroux Australians often say "I'm not racist I just hate Abos" and children make jokes like the following: Q: Why are Abo garbage cans often made of glass. A: So they can go window shopping. "The Happy Isles of Oceania" by Paul Theroux, Ballantine Books [∝]

The Aboriginal politician Norman Johnson once said, Australia is a "breeding place for bigots and rednecks." Aboriginals "are always drunk and hanging around town" white Aussies told Theroux in Alice Springs. "They're slobs, they're stupid. Their clothes are in rags—and they have money too. They're always fighting and sometimes they're really dangerous." Theroux said he smiled at this rant "because it was a true description of so many white Australians I had seen."∝

Queenslanders are well known for their prejudice against Aboriginals. When the premier of Queensland, Johannes Bjelke-Peterson, was asked by journalist William Ellis what he thought about Aboriginal rights he answered, "I think many people in high places have gone mad. I always maintain that if a Aboriginal came and held his bare toe up, they'd lick it. The federal government gives them all this money. They won't work. They don't need to work. They got more money than they could spend." Aboriginals, like American blacks before desegregation, seem fearful and timid.

In the early 1990's there were rumors floating around that it was the Jews not the Aboriginals that first settled Australia. Some Queenslanders were worried that the Jews would starting getting government money instead of the Abos. Many Queenslanders agreed that as bad it was giving all that money to the Aboriginals it was better than giving to the Jews.∝

Efforts to Address Racism Towards Aboriginals in Australia

Ilsa Sharp wrote in “CultureShock! Australia”: The deeper you get into the countryside, the worse the things you hear. To far too many white Australians, Aboriginals are still ‘boongs’ or ‘abo’s’, the old terms of contempt now taboo in polite urban society. Even my otherwise charming Aussie friend spelled it out for me: ‘They’re all bludgers (the Aboriginals), that’s what they are! Never worked for any land, never bought any land, just inherited it, that’s all!’ Blatant cases of discrimination still surface regularly in the press. In 1989, Aboriginal university graduate and youth welfare officer, Julie Marie Tommy, successfully sued a Western Australian pub-hotel for refusing to serve her at its bar. It transpired during the case that the hotel had also set aside separate whites-only and blacks-only bars. Such scenes are repeated endlessly throughout rural Australia today. [Source: Ilsa Sharp, “CultureShock! A Survival Guide to Customs and Etiquette: Australia”, Marshall Cavendish, 2009]

Aboriginal Linda Burney, a minister in the New South Wales government in the 2000s and 10 in 1967 when Aboriginals were given the right to vote told Reuters: “Whitefellas have to come to terms with the racism too many of them will accept and excuse, even if they don’t feel it themselves. Whitefellas need to look past their whiteness and try to feel what it is to ‘walk a mile in our shoes’,” said Huggins. “Many Australians will go through life having never met or spoken to an aboriginal person. If you do not know someone then you fear them and their culture.” [Source: Michael Perry, Reuters, May 24, 2007]

Huggins also said Aboriginals have to embrace reconciliation and seize the opportunities now available to improve their lives. Other black leaders have called for an end to “black welfare”. For blackfellas what needs to change is being able to accept that reconciliation...was always going to be a two-way street,” said Huggins, adding Aboriginals have to trust white Australia.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Culture Shock! Australia, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated September 2025