Home | Category: Aboriginals / Arts, Culture, Media

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL ARTISTS

Emily Kam Kngwarray painting Earth's Creation I in the Utopia region, Central Australia, 1994, from the Tate Gallery

Traditionally only Aboriginal men were allowed to paint. But now some of the most famous Aboriginal artists are women. Few Aboriginal artists have made as much money as the middlemen and galleries that deal in their work. Many Aboriginal artist don't own a car or a house. Some have few material possessions and earn little more than enough money to keep their families clothed and fed. Things have improved though.

Identifying artists and distinguishing their work from assistants and even forgers is problematic. The artist Gabrielle Possum Tjapaltjarri told the BBC, "Aboriginal art was first considered as a sort of traditional, cultural art, ad so it was okay for the artist to be there, and for all these other people to help. So, after a while, the artist participated less, until he wasn't there anymore....And so all the family could do the work, even if the artist wasn't there, and that was still considered that person’s painting. Once the academics, once the universities, once the big galleries accepted that it was okay for the family to help, that opened the door for the imitation industry.”

Tim Klingender, a Sotheby’s expert, mounted an important the 1994 exhibit of Aboriginal art. Geraldine Brooks wrote in The New Yorker: Klingender, divides his energy between Sotheby’s clients — whom he calls “the richest two hundred thousand people on the planet”— and Aboriginal communities, where the living conditions and the life expectancy rival those in the most dismal outposts of the developing world. At gallery openings, Klingender talks about Aboriginal art with a slick marketer’s spin; at home in Sydney, he speaks earnestly about his efforts to champion a culture once viewed as pathetic and doomed. [Source: Geraldine Brooks, The New Yorker, July 20, 2003]

Sotheby’s draws criticism from Aborigines and others who believe that artists should get a resale royalty on the sometimes staggering sums achieved at auction. The Papunya artist Johnny Warangkula Tjupurrula, for example, sold his canvas “Water Dreaming at Kalipinypa” for seventy-five dollars to a visiting artist in 1972. It ended up hanging in the owner’s laundry shed, just above the washing machine. In 1996, the owner of the painting asked Klingender to evaluate the work. Warangkula’s painting, he declared, was “a total masterpiece”; the work’s meshlike layering of stippled dots only partly veiled secret ceremonial objects and symbols that would become fully obscured in later Papunya works.

Klingender’s sales pitch was effective: Sotheby’s sold “Water Dreaming” at auction in 1997 for a hundred and fifteen thousand dollars; in 2000, it sold the work to a New York collector for two hundred and sixty-three thousand dollars. Warangkula, who died in 2001, received nothing from either of the sales, even though at the time he was crippled, partially blind, and destitute. Klingender told the Aboriginal community that the sales had revived interest in Warangkula’s art, allowing him to make a good living in his final years. The curator also organized a charity auction that raised funds for a dialysis clinic near the remote community of Kintore, where Warangkula died.

RELATED ARTICLES:

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIAN ART ioa.factsanddetails.com

VERY, VERY OLD AUSTRALIAN AND ABORIGINAL ROCK ART ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL PAINTINGS ioa.factsanddetails.com

MODERN AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL ART: PAPUNYA, MANGKAJA, REDISCOVERY, REVIVAL, AND A NEW AUDIENCE ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL ART FROM DIFFERENT REGIONS ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL ART OF NORTHERN AUSTRALIA: ANCIENT ROCK ART AND BARK PAINTINGS ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS (FIRST NATION PEOPLE) OF AUSTRALIA: NAMES, DEMOGRAPHICS, LANGUAGES ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINALS AT THE TIME EUROPEAN COLONIZATION BEGAN ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIA ABORIGINALS FROM 1900 TO PRESENT: DISCRIMINATION, ASSIMILATION, SOME RESTITUTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIA’S STOLEN GENERATIONS: VICTIMS, LAWS, RATIONALE, OUTRAGE ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL RELIGION: TRADITIONAL BELIEFS, DEMOGRAPHY AND DEATH ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL CUSTOMS, SOCIETY AND RITUALS ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL LIFE: WHERE THEY LIVE, WORK, DIET, HEALTH, ALCOHOL ioa.factsanddetails.com

TRADITIONAL ABORIGINAL LIFE: FOOD, HOMES, HUNTING ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL MEN AND WOMEN: GENDER, MARRIAGE, SEX ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIAN SEX: PRACTICES, ATTITUDES, ADOLESCENCE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS OF CENTRAL AUSTRALIA: SOME GROUPS, CUSTOMS, ART, LIFESTYLE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS IN WESTERN AUSTRALIA: SOME GROUPS, HISTORY, CUSTOMS, TRADITIONAL LIFE ioa.factsanddetails.com

Emily Kame Kngwarreye

Emily Kame Kngwarreye

Emily Kame Kngwarreye(1910-1996) is highly regarded Aboriginal painter. She is one of the most important abstract painters of the 20th century and one of the most significant artists that Australia has ever produced. She was born and brought up in Alhalkere on the edge of Utopia, northeast of Alice Springs in the Northern Territory, It has been said, "No artist has done more to shift the view of Australian indigenous art from the ethnographic domain into the contemporary art field." [Source: National Art Center, Tokyo, Utopia: the Genius of Emily Kame Kngwarreye]

Emily Kame Kngwarreye (or Emily Kam Ngwarray) was was a member of the Anmatyerre language group. The Anmatyerre and Alywarre peoples live in 20 small Aboriginal settlements in around 250 kilometers north-east of Alice Springs. After nearly a decade of working with the batik method, Kngwarreye started painting with acrylics on canvas in late 1988. A senior woman at the time, she created an incredible body of work over the next eight years that has endured and established her as one of Australia’s greatest painters. [Source: artst]

As an elder and ancestral protector, Kngwarreye spent decades painting for ceremonial purposes in the Utopia region. The emergence of artists from this region is linked to the formation of the Utopia Women’s Batik Group in 1977. Batik making began as a group effort, but over time, individual artists developed their own unique styles. Kngwarreye and 20 other women learned tie-dyeing, block painting, and batik methods through adult education programs at Utopia Station. Kngwarreye was a founding member of the group, which transitioned to using acrylics.

Kngwarreye once described her transition to acrylic painting as being less work suited for her advancing years: I did batik at first, and then after doing that I learned more and more and then I changed over to painting for good...Then it was canvas. I gave up on...fabric to avoid all the boiling to get the wax out. I got a bit lazy – I gave it up because it was too much hard work. I finally got sick of it ... I didn't want to continue with the hard work batik required – boiling the fabric over and over, lighting fires, and using up all the soap powder, over and over. That's why I gave up batik and changed over to canvas – it was easier. My eyesight deteriorated as I got older, and because of that I gave up batik on silk – it was better for me to just paint. [Source: Wikipedia]

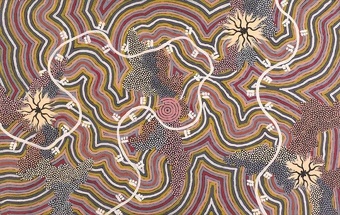

Art by Emily Kame Kngwarreye

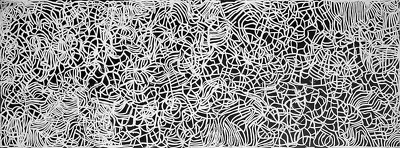

"Big Yam Dreaming", by Emily Kame Kngwarreye, 1995, synthetic polymer paint on canvas, 291 x 802 centimeters

According to the National Art Center in Tokyo, which hosted an exhibition of Kngwarreye’s work: Emily's strikingly modern and beautifully innovative works were created in an environment far away from the influence of the Western Art tradition. Her works have been featured in more than 100 exhibitions over the last decade and they are housed in collections around the world. In 1997, Emily's works were exhibited at the Venice Biennale and visitors from all over the world were deeply impressed by the richness of her art. As modern art, Emily's works transcend the Aboriginal art genre and now, more than ten years after her passing, they are highly acclaimed and recognized throughout the world. Emily first began working on canvas in her late seventies and she produced between three thousand to four thousand works in the eight years prior to her death. Emily's genius was nurtured in the Australian outback and her world provides a wealth of inspiration. [Source: National Art Center, Tokyo, Utopia: the Genius of Emily Kame Kngwarreye]

Works by Kngwarreye stem from a deep connection her tribal homeland, Alhalkere. The Museum of Contemporary Art Australia describes her subject matter as the "essence" of that region, with references to flora, fauna and Dreamtime figures from her environment. These include: Arlatyeye (pencil yam), Arkerrthe (mountain devil lizard), Ntange (grass seed), Tingu (a Dreamtime pup), Ankerre (emu), Intekwe (a favourite food of emus, a small plant). Atnwerle (green bean) and Kame (yam seed pod).

The pencil yam, or anwerlarr, is a vine with heart-shaped leaves and bean-like seed pods and was an important food source for Aboriginal people of the desert. It was also a central theme in many of her paintings; she often began her works by tracing the yam’s tracking lines. The plant held special personal significance for her as well—her middle name, Kame, refers to the yellow flower and the seeds of the pencil yam.

In 1995, in the last year of her life, she painted “Anwerlarr Anganenty” ("Big Yam Dreaming"), on a huge canvase measuring over 8 meters (26 feet) by nearly 3 meter (9.8 ft). This work signifies her principal Dreaming, the anwerlarr (pencil yam, Vigna lanceolata sp.), associated with her birthplace, Alhalker. This audacious monochrome work, painted continuously over two days in her penultimate year, recalls her batiks of 1977–88 in which fluid lines derived from women’s awely ceremonies prevail over dots. Thus the work of Kngwarray’s late career is deeply rooted in her beginnings as an artist and in making arlkeny (body markings) for awely ceremony. [Source: Victoria government]

The vast composition, accomplished in a single, continuous stroke, conceptualises the veins, sinews and contours of Alhalker, seen from a planar perspective. Embracing the monumental surface, Kngwarray’s holistic vision is sustained in all of the minute sections, through contrasting rhythms: angular, meandering long stretches, short jabs of tension, energetic rushes and volatile lines. The intuitive drawing signifies the subterranean roots of the long tuberous vegetable, the cracks that form in the ground when the pencil yam ripens and the striped body paintings worn by Anmatyerr women in awely ceremonies. In conceptual works such as this late masterwork or her earliest colourist canvases of layered dots, Kngwarray initiated a revolution. Her art resisted interpretation as any kind of narrative, map-making, diagram or landscape: it was no longer notation but a form of visual music.

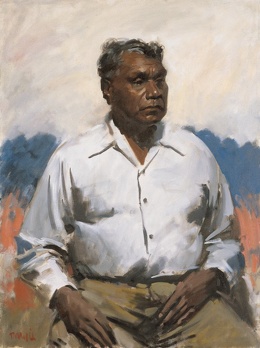

Albert Namatjira

Albert Namajira (1902-59) was a pioneer of contemporary Indigenous Australian art and was Australia’s first well recognized Aboriginal artist. The first Aboriginal to become a naturalized Australian citizen, he painted European-style landscapes with images and symbols that had a deep meaning to Aboriginals. He lived at Hermannsburh Lutheran Mission, 130 kilometers (80 miles) west of Alice Springs. A years after he was made a citizen he was jailed for supplying liquor to Aboriginals. A year after that he died at the age of 57.

Albert Namatjira was born with the name Elea Namatjira. He was a member of the Arrernte group and lived around the MacDonnell Ranges in Central Australia. He is widely considered as one of Australia’s greatest and most influential artists. Rex Batterbee, an Australian painter, educated Aboriginal artist Albert Namatjira and other Aboriginal artists western style watercolor landscape painting at the Hermannsburg mission in the Northern Territory beginnin in 1934.

Namatjira’s popular style was known as the Hermannsburg School. His paintings sold out when they were shown in Melbourne, Adelaide, and other Australian cities. As a consequence of his reputation and popularity with his watercolor paintings, Namatjira became the first Aboriginal Australian citizen.

In 1956, William Dargie’s portrait of Namatjira became the first to win the Archibald Prize for an Aboriginal individual. Namatjira was awarded the Queen’s Coronation Medal in 1953, and he was commemorated on an Australian postage stamp in 1968. According to “CultureShock! Australia”: Namatjira scored most of his considerable success before World War II and did it with Western-style watercolour paintings. More traditional Aboriginal art was not to win white acclaim until long after the war.

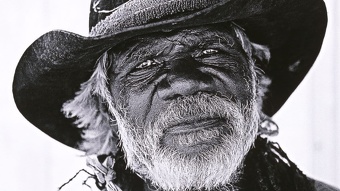

Rover Thomas

Rover Rover Thomas, also known as Thomas Joolama (c.1926 – 11 April 1998), was an Aboriginal Australian artist. He was born in 1926 in Gunawaggii, at Well 33 on the Canning Stock Route in Western Australia’s Great Sandy Desert. At the age of ten, Thomas and his family relocated to the Kimberley, where he started working as a stockman, as was customary at the time. Thomas resided in Turkey Creek later in his life. [Source: artst]

In 1977, Thomas and his Uncle Paddy Jaminji began painting dancing boards on dismantled tea chests for the Krill Krill event. Thomas began painting ocher on canvas in the early 1980s and quickly became a pioneer artist of what became known as the East Kimberley School. The Paintings of Rover Thomas are shown at the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra. In 1994, he was the focus of the significant solo exhibition Roads Cross: Thomas’ work was one of eight solo and collaborative groups of Indigenous Australian artists shown at Russia’s famed Nicholas Hall at the Hermitage Museum in 2000.

Geraldine Brooks wrote in The New Yorker: Thomas’s interest in painting had spiritual origins. On Christmas Day in 1974, a devastating cyclone flattened the city of Darwin, which is the main center of European influence in northern Australia. Aboriginal elders interpreted the devastation as a manifestation of the anger of ancestral spirits known as Rainbow Serpents, who were said to be enraged that white influence had caused neglect of their land and rituals. Thomas was one of many Aborigines who reacted to reports of the catastrophe in a metaphysical way. He told friends and family that he had been visited by a spirit, who offered him a vision of a new ritual, the Krill Krill. At the first performance of this ceremony, dancers carried wooden boards that Thomas had designed with earth-toned fields of ocher. [Source: Geraldine Brooks, The New Yorker, July 20, 2003]

Around the same time, a nurse named Mary Mácha went to work for the Western Australian government’s Native Welfare Department. Her job was to raise money for impoverished communities by selling their crafts. At Turkey Creek, she met Rover Thomas, who told her that he wanted to paint. Convinced of his talent, Mácha set up a studio for Thomas in her garage. She would prop his pictures against the fences in the narrow lane behind her house and sell them to anyone she could interest. Eventually, collectors started seeking out Thomas’s graceful, minimalist work. Painted in natural earth pigments, their creamy browns and blacks evoked the rounded rock forms of the Kimberly ranges nearby.

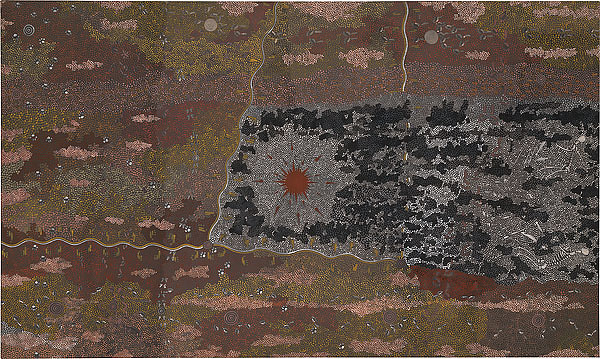

Bungullgi (1989) is regarded as a masterpiece of Rover Thomas’s minimalist style, was painted in 1989. It shows the contours of the hilly terrain near the Argyle Diamond Mine exit in east Kimberley. In the shape of a big toe, the rock at the top left represents a Dreamtime man who waited too long for his dogs and became a rock. The essence of these hills is perfectly captured in this sparsely composed work. Winding cattle trails and the Argyle Mine's access routes are depicted using natural earth pigments. It sold for $310,000 at hammer, $380,455 including the buyer's premium. [Source: Urban Splatter December 1, 2021]

Impact of Rover Thomas's Work

The art scene in Western Australia was sparked by Thomas. Many East Kimberley artists, including Queenie Mckenzie, Freddie Timms, and Paddy Bedford, were inspired by him. Geraldine Brooks wrote in The New Yorker: Wally Caruana, then a curator at the National Gallery of Australia, was among the first connoisseurs to appreciate Thomas’s spare and unusual paintings. In 1984, he arranged for the gallery’s director to meet Mácha. Afterward, Caruana recalled, the director told him, “You introduced me to a grandmother with a plastic shopping bag, and in it were the most marvellous paintings I’ve ever seen.” [Source: Geraldine Brooks, The New Yorker, July 20, 2003]

The work had arrived just as there was an audience primed to receive it. “We had learned to appreciate contemporary movements such as Abstract Expressionism and minimalism, and then suddenly here is this work that has the same aesthetic, yet is loaded with multiple meanings,” Caruana said. The visual correspondence between Aboriginal works and modern art was all the more striking, given that artists like Thomas had never studied Western painting.

In 1990, Caruana invited Thomas to Canberra, so that the artist could see, for the first time, an extensive collection of modern art. Caruana was walking with Thomas through the National Gallery when he suddenly stopped in front of one painting. “Who’s that bugger who paints like me?” he asked. The painting, “1957 #20,” by Mark Rothko, is eerily similar to Thomas’s work.

Thomas, who died in 1998, was quickly embraced by the Western art market. A 1991 painting depicting a waterfall seems to bend the picture plane at the point where the channels of water reach the cliff edge and then cascade downward. To Caruana, the painting “represents the epitome of Thomas’s approach.” Two years ago, he acquired the work, titled “All That Big Rain Coming from Top Side,” for the National Gallery of Australia, at a price of about four hundred thousand dollars. It was a record for Aboriginal art sold at auction.

Queenie McKenzie and Pijaju Peter Skipper

Geraldine Brooks wrote in The New Yorker: Thomas’s success inspired many other Aborigines to paint. In 1992, his sister, Nyuju Stumpy Brown, married Hitler Pamba and settled in a community near Fitzroy Crossing. Brown started to paint her own images of lost country, and Pamba followed suit. [Source: Geraldine Brooks, The New Yorker, July 20, 2003]

A neighbor,Pijaju Peter Skipper, began to make simple works that reproduced punarrapunarra—the kinds of repetitive patterns he might once have incised on a shield. Skipper’s sustained feelings of exile, however, eventually led to a more profound form of artistic expression. When he describes his work, he uses two Walmajarri words, wangarr and mangi, that have no precise English equivalents. Wangarr is the ghost image of someone; mangi is a combination of the spirit and the physical trace of a person, which remains discernible even after he has left. When whites mined the earth or made roads,

Skipper explained, “they scraped the mangi off the land,” and the essence of the past inhabitants was lost. For him, painting was a way to make wangarr, or shadow images, of what was now gone, and thus restore mangi. Skipper began obsessively painting the water hole for which his father had been the hereditary custodian. Its distinctive quatrefoil shape, rendered in acid greens or vivid oranges, became a focal point in many of his works.

Queenie McKenzie (1915 until 1998) e was born on Old Texas Station, on the Ord River’s western bank in East Kimberley. She was in danger of being removed from her home by the government throughout her childhood, as were many other Aboriginal children of mixed ancestry at the time. Her mother, on the other hand, supposedly prevented her child’s displacement by blackening her complexion with charcoal, and the little girl grew up working for the stockmen of the Texas Downs cattle ranch. [Source: artst]

McKenzie was helped by the Waringarri Aboriginal Arts Corporation, which was established to guarantee that Aboriginal art is respected in terms of copyright and moral rights, and that Aboriginal artists be appropriately compensated for their work. A painting by McKenzie portraying the Mistake Creek Massacre was purchased by the National Museum of Australia in 2005, but it was never mounted owing to debate regarding the facts of the event, which was part of the History Wars. It will be on display at the Museum beginning in July 2020 as part of a new exhibition titled “Talking Blak to History.”

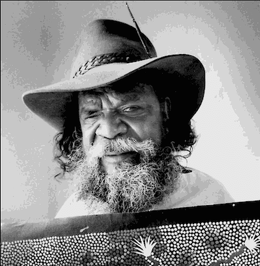

Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri

Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri (1932–2002) was a well-known and well-collected Australian Aboriginal artist. He was the most well-known of the painters who resided in the Papunya region of the Northern Territory’s Western Desert when the acrylic painting technique (popularly known as “dot art”) was introduced. His works may be found in galleries and collections across the world, including the Art Gallery of New South Wales, the National Gallery of Australia, the Kelton Foundation, and the Royal Collection.

Following his father’s death in the 1940s, his mother married Gwoya Jungarai, better known as One Pound Jimmy, whose portrait appeared on a popular Australian postage stamp. Tim Leura Tjapaltjarri, whose artwork appears on another stamp, was his brother. In the early 1970s, Geoffrey Bardon visited Papunya and encouraged the Aboriginal people to paint their dreaming tales, which had previously been rendered ephemerally on the ground. [Source: artst] . Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri rose to prominence as one of the forefathers of the Western Desert Art Movement, a school of painting. Possum belonged to the Anmatyerre culture-linguistic group, which lived in the Alherramp (Laramba) village. He passed away in Alice Springs on the day he was to be awarded the Order of Australia for his services to art and the Indigenous community.

Tjapaltjarri’s “Warlugulong 1977” was one of five large canvases produced by Tjapaltjarri in which he blended ceremonial ground paintings and European-style topographical maps to depict his ancestral land in the outback Western Desert. The painting, sold in the year it was painted for just A$2,500. In 2007, according to to Reuters, it smashed the Australian record for indigenous when it sold for A$2.4 million art at a time when the country’s art market has been booming, underpinned by cashed-up mining and commodity investors.

Minnie Pwerle and Dorothy Napangardi

Minnie Pwerle (1910 and 1922 – 2006) was an Aboriginal artist from Utopia, Northern Territory (Unupurna in local language), a cattle ranch in Central Australia’s Sandover region 300 kilometers (190 miles) northeast of Alice Springs. Minnie started painting at the age of 80 in 2000, and her images quickly became prominent and sought-after works of modern Indigenous Australian art. [Source: artst]

Minnie’s paintings were shown across Australia and acquired by major institutions, including the Art Gallery of New South Wales, the National Gallery of Victoria, and the Queensland Art Gallery, from the time she began painting on canvas until her death in 2006. With her prominence came the pressure from people who wanted to buy her art. She was supposedly “kidnapped” by someone who wanted her to paint for them, and her work has been faked, according to media sources. Minnie’s art is often likened to that of her sister-in-law Emily Kame Kngwarreye, who also hails from Sandover and began painting in acrylics later in life. Barbara Weir, Minnie’s daughter, is a well-known artist in her own right.

Dorothy Napangardi (born early 1950s – 2013) was born in the Tanami Desert and worked in Alice Springs. She grew raised in Yuendumu, a settlement town, and lived the most of her life in Alice Springs, where she started painting in 1987. She had limited formal education but was taught about her people’s historical Dreaming. The term ‘Dreaming’ is an imperfect English translation of the Warlpiri word ‘Jukurrpa,’ which narrates the origins and migrations of ancestral creatures in the land and marks holy sites where the spirits live.

In general, the Jukurrpa theme is one of the inseparability of the individual from the environment, and it commonly incorporates journey over the land. These are ideas that can also be seen in Napangardi’s work, which has a plethora of crossing lines that convey spiritual significance and emotive depth. “To me, Dorothy’s art is like Yapa (people) flowing through and over their nation, traveling through their paths when they go traveling,” a Warlpiri speaker said in a catalogue of Napangardi’s work. In June 2013, Napangardi was killed in an automobile accident.

Highest Prices Paid for Aboriginal Artworks

The Australian economy gains $100 million annually from the sale of Aboriginal art. The highest prices ever paid for an Australian Aboriginal artwork was US$2.1 million for different paintings: 1) in 2017 for Emily Kame Kngwarreye's painting, “Earth's Creation I” (1994) and 2) in 2007 for Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri's painting “Warlugulong” (1977). There is some ambiguity over the valuations of these art works due to exchange rate difference between the Australia and U.S. dollars and inflation over time. [Source: Urban Splatter December 1, 2021]

Kngwarreye's painting “Earth's Creation I” was sold on Cooee Art Marketplace and Fine Art Bourse's online auction to Tim Olsen, an art dealer in New York, for a newly opened gallery. The Commonwealth Bank purchased Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri's Warlugulong for AU$1,200 in 1977. The bank sold the painting in 1996 for AU$36,000. The National Gallery of Australia paid AU$ 2.4 million (US$2.1 million) for it in a Sotheby's auction in July 2007.

“Water Dreaming” by Johnny Warangkula Tjupurrula reportedly sold for US$150 in 1973. The painting was sold for US$486,500 in 2000, a 3,243 percent increase in just 27 years.

Tommy Lowry Tjapaltjarri's most celebrated work, “Two Men Dreaming at Kuluntjarranya”, 1984, (lot 51) has an estimated value of US$225,000–US$338,000. Collectors regard it as one of Aboriginal’s art most aesthetically pleasing and exceptional paintings, and it has been shown in two of the field's most prestigious exhibitions: Dreamings.

Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri's "Warlugulong"

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, National Museum of Australia

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Culture Shock! Australia, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated October 2025