Home | Category: History / Aboriginals

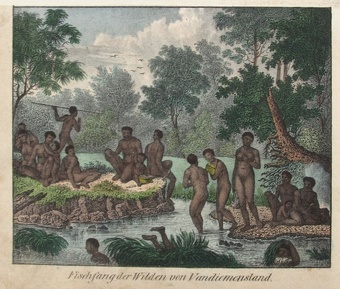

ABORIGINAL TASMANIANS

Aboriginal Tasmanians were separated from the rest of humanity for almost 8,000 years — the record for the longest isolation in human history. Aboriginal Tasmanians arrived in Tasmania from mainland Australia around 35,000 years ago when water levels dropped 120 meters (400 feet) during an Ice Age glacial maximum about 10,000 years ago then they were cut off from the Australia mainland when sea levels rose around 8,000 years ago and neither Aboriginal Tasmanians or mainland Aboriginal ventured across the Bass Strait to see visit the other it seems. There is no record of trade between Tasmanian societies nor between Tasmanians and peoples of Australia or other Pacific islands. [Source: Discover, March 1993 ∩; [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

Tasmania is an island that covers about 67,000 square kilometers (35,870 square miles) and is located about 240 kilometers (150 miles) southeast of mainland Australia. The two land masses are separated by the rough waters of the Bass Strait. Tasmania is a state of Australia. At one time it was a peninsula of Australia but was cut off by rising waters about 7,000 to 8,000 years ago. Tasmanian is a mountainous island, with a variety of ecological zones, considerable rainfall, and a generally mild climate. Land mammals such as kangaroos, wallabies, and native dogs are relatively abundant as are seals, shellfish, and birds. |~|

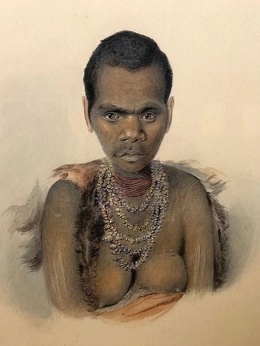

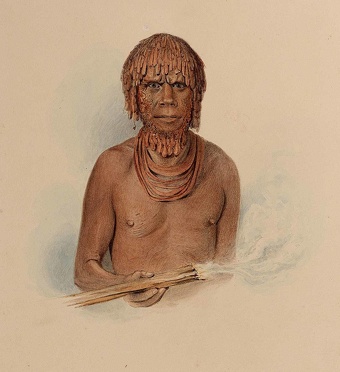

Aboriginal Tasmanians referred to themselves as Palawa or Pakana. Despite the fact that icy winds bring snow to Tasmania's mountains in the winter time anthropologists assert that Aboriginals on the island went around naked the entire year. For protection they smeared themselves with a mixture of animal fat, charcoal and ocher. Scholars estimate that between five and twelve distinct languages were spoken by Aboriginal Tasmanians, sharing certain grammatical, phonological, and lexical features. However, the relationship of these languages to other mainland Australian language families is not well understood. |~| ∩

Tasmania was first inhabited 35,000 years ago by people with sophisticated toolmaking skills.. By the 18th century, Tasmanians used simple technology, hunting with rocks and crude clubs. In 2004 anthropologist Joseph Henrich used a mathematical model of cultural evolution to expalin how this could happen. He concluded that the island’s population, about 4,000 in the 18th century, at some point fell below the level necessary for complex skills to be passed from generation to generation. Scientists increasingly think population size and density have had a big impact on human development at certain pivotal points. That continues in the modern world, as young people disproportionately produce innovation, generate economic growth, and finance social support networks for the elderly. [Source: Michael Balter, Discover October 18, 2012]

Aboriginal Tasmanian people were widely, and erroneously, thought of as extinct and intentionally exterminated by white settlers. In 2016 it was estimated that the number of people of Aboriginal Tasmanian descent was 6,000 to over 23,000 varying according to the criteria used to determine Aboriginal Tasmanian identity. [Source: Wikipedia]

RELATED ARTICLES:

ABORIGINALS (FIRST NATION PEOPLE) OF AUSTRALIA: NAMES, DEMOGRAPHICS, LANGUAGES ioa.factsanddetails.com

EARLY MODERN HUMANS IN AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

LIFE OF EARLIEST HUMANS IN AUSTRALIA: TOOLS, WEAPONS, ART, SETTLEMENTS ioa.factsanddetails.com

PEOPLE WHO LIVED AUSTRALIA 20,000 TO 10,000 YEARS AGO ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

RITUAL LIFE AND MYTHS OF ANCIENT AUSTRALIANS ioa.factsanddetails.com

EARLY ABORIGINALS ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

VERY, VERY OLD AUSTRALIAN AND ABORIGINAL ROCK ART ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINALS AT THE TIME EUROPEAN COLONIZATION BEGAN ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL TASMANIANS: HISTORY, ABUSE, LIFESTYLE AND NEAR EXTINCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIA ABORIGINALS FROM 1900 TO PRESENT: DISCRIMINATION, ASSIMILATION, SOME RESTITUTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIA’S STOLEN GENERATIONS: VICTIMS, LAWS, RATIONALE, OUTRAGE ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL RELIGION: TRADITIONAL BELIEFS, DEMOGRAPHY AND DEATH ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL CUSTOMS, SOCIETY AND RITUALS ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL LIFE: WHERE THEY LIVE, WORK, DIET, HEALTH, ALCOHOL ioa.factsanddetails.com

TRADITIONAL ABORIGINAL LIFE: FOOD, HOMES, HUNTING ioa.factsanddetails.com

Aboriginal Tasmanian History

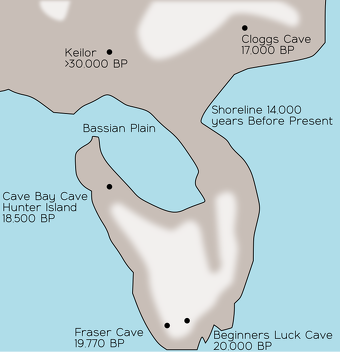

Shoreline of Tasmania and Victoria about 14,000 years ago as sea levels were rising, with some human archaeological sites

Tasmania was occupied by successive waves of Aboriginal people from southern Australia beginning around 35,000 years during glacial maxima, when the sea was at its lowest. The archeological and geographic record suggests a period of drying during the colder glacial period, with a desert extending from southern Australia into the midlands of Tasmania, with intermittent periods of wetter, warmer climate. Migrants from southern Australia into peninsular Tasmania would have crossed stretches of seawater and desert, and finally found oases in the King highlands (now King Island). [Source: Wikipedia]

In 1990, archaeologists excavated Tasmanian Aboriginal material in the Warreen Cave in the Maxwell River valley of southwest Tasmania dated to 34,000 years ago, providing form evidence that people lived in Tasmania at that time and making Aboriginal Tasmanians the southernmost population in the world during the Pleistocene era. Digs in southwest and central Tasmania turned up abundant finds, affording "the richest archaeological evidence from Pleistocene Greater Australia" from 35,000 to 11,000 years ago,

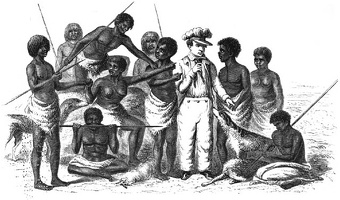

When Tasmania was 'discovered" in 1642 by Dutch captain Abel Tasman there were approximately 3,000 to 5,000 Aboriginals in nine tribes living on the island. They were similar in appearance to mainland Aboriginals except their hair was wooly. Tasman did not encounter any of these people who were not discovered until Frenchman Nicholas Marion du Fresne and his crew shot a couple of them about a hundred years later. At first, contact with the Aboriginal Tasmanians was cordial, friendly; however the Aboriginals became alarmed when another boat was dispatched towards the shore. Spears and stones were thrown and the French responded with musket fire, killing at least one Aboriginal person and wounding several others. Two later French expeditions led by Bruni d'Entrecasteaux in 1792–93 and Nicolas Baudin in 1802 made friendly contact with the Aboriginal Tasmanians; the d'Entrecasteaux expedition doing so over a farily long period of time.

Before British colonisation of Tasmania in 1803, there were an estimated 3,000 to 15,000 Aboriginal Tasmanians. Captain James Cook visited in 1773 but made no contact with the Aboriginal Tasmanians although gifts were left for his crew in unoccupied shelters found on Bruny Island. The first known British contact with the Aboriginal Tasmanians was on Bruny Island by Captain Cook in 1777. The contact was peaceful. Captain William Bligh also visited Bruny Island in 1788 and made peaceful contact with the Aboriginal Tasmanians.

Aboriginal Tasmanians and the Sealers

The first white people to stay for any length of time on Tasmania were British and American sealers sealers (seal hunters) who arrived in the late 1790s. The Aboriginal people traded kangaroo skins for goods they desired such as hunting dogs, flour, tea and tobacco. However, a trade in Aboriginal women soon developed. Many Tasmanian Aboriginal women were highly skilled in hunting seals, as well as in obtaining other foods such as seabirds like muttonbirds..

Initially, Tasmanian tribes trade the services of their women to the sealers for the seal-hunting season. Later these women were sold on a permanent basis. This trade sometimes involved in women abducted from other tribes. Later sealers engaged in raids along the coasts to abduct Aboriginal women.

Historian James Bonwick reported on Aboriginal women who were clearly captives of sealers but he also reported on women living with sealers who "proved faithful and affectionate to their new husbands", women who appeared "content" and others who were allowed to visit their "native tribe", taking gifts, with the sealers being confident that they would return. [Source: Wikipedia]

By 1810, seal numbers had been greatly reduced by hunting so most sealers abandoned the area, however a small number of sealers, approximately fifty mostly "renegade sailors, escaped convicts or ex-convicts", remained as permanent residents of the Bass Strait islands and some established families with Tasmanian Aboriginal women.

Sealing captain James Kelly wrote in 1816 that the custom of the sealers was to each have "two to five of these native women for their own use and benefit". A shortage of women available "in trade" resulted in abduction becoming common, and, in 1830, it was reported that at least fifty Aboriginal women were "kept in slavery" on the Bass Strait islands: “Harrington, a sealer, procured ten or fifteen native women, and placed them on different islands in Bass's Straits, where he left them to procure skins; if, however, when he returned, they had not obtained enough, he punished them by tying them up to trees for twenty-four to thirty-six hours together, flogging them at intervals, and he killed them not infrequently if they proved stubborn.”

Aboriginal Tasmanian Lifestyle

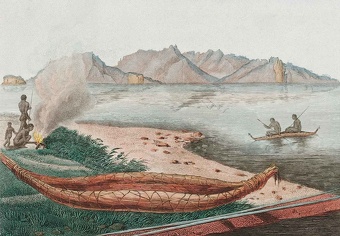

Indigenous Tasmanian reed canoe seen on the eastern shore of Schouten Island by Charles-Alexandre Lesueur in 1807

The Aboriginal Tasmanians in the 18th and 19th centuries were one of the most "primitive" groups of people ever known. Even though some parts of Tasmania receives five times as much rain as Seattle the people didn't live in houses or lean-tos. Nor did they know how to fish. The Aboriginal Tasmanians had no metal tools. They also lacked hatchets, nets, traps, hooks, fire-making drills, and spear throwers, all of which were used by Aboriginals on the mainland. The Tasmanian tool kit was limited largely to objects made from wood, stone, and shell. Long wooden spears, clubs and throwing sticks were the main weapons, and flaked stone knives and scrapers were used for shellfish gathering and food preparation. Shellfish shells served as cooking vessels, along with kelp baskets and baskets and nets twined from grass, reeds, and bark. The main tools were stone scrappers and wooden digging tools. Points and spatulas made from wallaby bones were used perhaps for preparing hides.

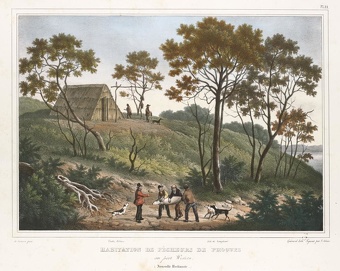

It is unclear whether the Tasmanians were nomadic, moving to new encampments every day or two, or transhumant, moving inland in the warm months and to the sea in the colder months. Evidence suggests regional variation in settlement patterns: groups in the west appear to have been more settled than those in the east. In all cases, settlement locations were closely tied to the availability of food. Tasmanian societies were territorial, and incursions into another group’s land typically resulted in conflict. Nomadic groups built simple bark windbreaks for shelter, whereas more settled communities constructed beehive-shaped huts, often clustered along rivers or lagoons. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Fires were lit with a pieces of burning coal carried with them at all times.. When their last coal was extinguished, Tasmanian Aboriginals would ask for fire from neighboring hearths or clans, but also probably used friction fire-starting methods and possibly mineral percussion despite claims that the native Tasmanians had "lost" the ability to make fire. Tasmanian Aboriginal people extensively employed fire for cooking, warmth, tool hardening and clearing vegetation to encourage and control macropod herds. This management may have caused the buttongrass plains in southwest Tasmania to develop to their current extent. [Source: Wikipedia]

Aboriginal Tasmanians possessed watercraft, reed baskets, water containers and mortars and pestles. They weaved plant fibers into baskets and made buckets from kelp. Their reed boats, which were sometimes propelled by a pushing woman were not very seaworthy. They became waterlogged after several hours in the ocean and sank.

Tasmanian Aboriginal Families and Society

Tasmanian Aboriginal households — typically monogamous or polygynous families, sometimes joined by additional relatives — formed the basic residential, productive, and consumption units. Early reports describe large families, though later accounts note a decline in family size, partly due to abortion and infanticide after European contact. Marriage was community-exogamous, (outside one’s group) and many men obtained wives by capturing women from other groups, though arranged marriages also occurred. Most unions were monogamous, but older men might take multiple wives. Divorce was permitted, and widows became the responsibility of their husband’s community, reflecting the generally lower status of women compared to men. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

Children were primarily raised by their mothers, with both parents showing indulgence and avoiding physical punishment. Childhood centered on learning essential skills — hunting, gathering, climbing, building, and tool-making — that prepared them for adult life. At puberty, boys underwent an initiation marked by scarification, naming, and the bestowal of a fetish stone. No equivalent rite of passage for girls has been reported.

Little is known about Tasmanian kinship systems or terminology. Their societies lacked formal leaders and were not organized as corporate landholding or war-making units. Instead, each society comprised five to fifteen named communities of thirty to eighty related individuals, further subdivided into households. These communities were the key landholding and war-making units, often led by an older man respected for his hunting skills, though his authority was limited outside times of conflict. Community identity was expressed through shared myths, dances, songs, and hairstyles. Affiliation with other communities within the same society was relatively weak, but was evident in the reluctance to fight against them and the willingness to allow mutual land use. Elders were afforded some prestige, and evidence suggests three male age grades, with ceremonies marking progression between them.

Although individuals owned weapons, ornaments, and other personal possessions, land itself was not individually held. Instead, each community controlled access to a territory ranging from 300 to 5,600 square kilometers. Unauthorized use of land was the most common cause of warfare, especially between communities belonging to different societies.

Without centralized leadership, social order was maintained collectively. Disputes were often resolved through throwing-stick duels, while breaches of custom could result in group ridicule. More serious offenses against the community were punished by forcing the offender to stand still while spears were hurled at him, with survival depending on his ability to dodge. Inter-community warfare, particularly between societies, was reported to be frequent — though this may have been intensified after European contact. The main causes of conflict were trespassing and the abduction of women, and fighting generally took the form of raids or skirmishes that rarely caused more than a single death.

Aboriginal Tasmanian Religion and Art

Little was recorded of traditional Tasmanian Aboriginal religion and spiritual life. Early British settlers said Aboriginals described valleys and caves as being inhabited by "sprites". George Augustus Robinson (1791-1866), who wrote extensively about Tasmanian Aboriginals and their demise, said that members of some clans had animistic regard for certain species of tree. Robinson recorded several discussions on spiritual entities capable of aiding people in their physical world. Tasmanian Aboriginal people described these entities as "devils" that walked alongside them "carrying a torch but could not be seen". [Source: Wikipedia]

Tasmanian religious beliefs centered on ghosts and their influence on the living. Though spirits of the dead were sometimes seen as helpful, they were more often feared as sources of harm and suffering. Burial grounds were avoided, and the names of the dead were taboo. Beyond ghosts, Tasmanians also recognized more powerful spiritual beings, including a thunder demon, a moon spirit, and malevolent entities thought to inhabit dark places such as caves and hollow trees. Magic and witchcraft were central to their worldview, with death and illness commonly attributed to malevolent spirits or sorcery. Objects such as bones of the dead and particular stones were believed to hold protective, healing, or destructive powers. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

Healing was undertaken by part-time shamans who employed bleeding, sucking, bathing, massage, and plant-based remedies. They also drew upon supernatural forces, entering possession trances and using ritual instruments such as rattles made from human bones. Community dances were another vital form of religious, artistic, and social expression. Men often danced to the point of collapse, while women kept rhythm with sticks and rolled-bark drums. Male religious dances were closed to women, who appear to have had their own secret dances focused on female roles, such as root-digging or child-rearing. Initiation ceremonies for boys and age-grade rites were of major social importance, though ceremonies marking birth and marriage were not recorded.

The dead were typically disposed of quickly, most often through cremation followed by burial of bones and ashes, though some bones might be kept and worn by relatives. On the night of the burial, the entire community gathered at the grave, keeping vigil and wailing until dawn. Widows engaged in acts of mourning by cutting and burning their bodies, shearing their hair, and placing the hair upon the grave. Each person was thought to have a soul that continued after death as a ghost. The afterlife was imagined as similar to earthly existence, but without the presence of evil.

Their art included stenciled hands found deep in caves. Small tools known as "thumbnail scrapers" may have been used for woodworking. According to 18th century European explorers, they built substantial shelters from wood and bark and decorated the insides with drawings of women, men, animals and symbolic designs. They sang songs recounting heroic deeds of the singers and their ancestors. The most elaborate artistic expression, however, was body adornment. Men colored their hair and skin with charcoal, clay, and grease, while both men and women wore flowers and feathers in their hair. They incised their bodies with circles, lines and dashes. Such scarification was practiced by both sexes and often consisted of patterned rows of dark scars enhanced with rubbed-in charcoal.

Aboriginal Tasmanian Food, Hunting and Gathering

Aboriginal Tasmanians had no agriculture and no domesticated animals but made use of nearly every available source of food in their environment. Kangaroos, wallabies, wombats, platypuses, possums, emus seals were hunted with spears. Their principal prey were red-necked wallabies. Snakes, lizards, snails, insects, eggs, scallops, abalone,other shellfish, birds and their eggs were collected; and roots, fungi, berries, and native tubers were gathered. Fish-eating was considered taboo. When Europeans arrived and gobbled down the fish they caught the Aboriginals looked on with disgust. While there is some evidence of communal hunting — particularly of kangaroos, birds, and plant foods — subsistence was generally the responsibility of small household units consisting of a man, a woman, and their children. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996; Discover, March 1993]

Chores among the Aboriginal Tasmanians were divided along sexual lines. Men made the wood and stone tools, hunted for wallabies and other large animals, and fought in wars with other island societies. Women did most everything else, including building the windbreaks and huts, gathering water, hunting possums by scaling trees, collecting plants, combing the beach for shellfish and diving into waters too cold for a man to collect abalone and lobsters. Early British and American sealers said Aboriginal Tasmanian women were very good at hunting seabirds and seals. ∩

About 4,000 years ago, Aboriginal Tasmanians for the most part stopped eating fish and began eating more land mammals, such as possums, kangaroos, and wallabies. Around this time they switched from worked bone tools, believed to have been primarily used for fishing, to more efficient sharpened stone tools. Fish were never a large part of Aboriginal diet, ranking behind shellfish and seals. Archaeological evidence indicates that around the time switch from bone to sharp stone tools occurred Tasmanian Aboriginals began expanding their territories, a process that was still continuing when Europeans arrived. [Source: Wikipedia]

Aboriginal Tasmanian Abuse and Hardships at the Hands of Whites

The Aboriginal population of Tasmania was completely wiped out by whites in the mid 18th century about a hundred years after the island was settled by Europeans. The first British settlers came in 1803, when Britain's most hardcore convicts were sentenced to years of hard labor at Port Arthur, the most notorious of the Australian penal colonies which had a lot in common with France's Devil's Island.

The English regarded the Tasmanians as subhuman and hunted them down; the Tasmanians responded by both fighting back and retreating farther and farther inland. Between 1803 and 1823, there were two phases of conflict between Aboriginal Tasmanians and the British colonists. The first, between 1803 and 1808, was over common food sources such as oysters and kangaroos, and the second, between 1808 and 1823, occurred as a result of there being only a small number of white females among the colonists, and farmers, sealers and whalers engaged part in the trading, and the abduction, of Aboriginal women as sexual partners. These practices also increased conflict over women among Aboriginal tribes. This in turn led to a decline in the Aboriginal population. Historian Lyndall Ryan records 74 Aboriginal people (almost all women) living with sealers on the Bass Strait islands in the period up to 1835. [Source: Wikipedia]

Sealers and escaped convicts bought and kidnapped Aboriginal women and children, often killings the husbands and fathers in the process. Some white men possessed as many as five Aboriginal women which were kept for sex and slave labor. Some of the women were tied up when they weren't working and others were shot if they didn't work hard enough or attempted to escape. [Source: Discover, March 1993 ∩]

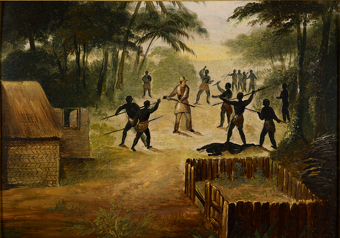

Aboriginals and settlers also had numerous conflicts, especially in the fertile Midland Valley, where Aboriginal hunting lands were granted to settlers for wool production. Once 300 Tasmanian hunters were chasing a herd of kangaroos that led them near a British camp, where a jittery solider opened fire. The Tasmanians retaliated, killing several British.

Killing of Aboriginal Tasmanians by Whites

For all intents and purposes no punishments were inflicted on Europeans for murdering a Aboriginal Tasmanian. Some white men received a sentence of 25 lashes for tying Aboriginal women to logs and burning them with a hot coal or for forcing them to wear the head of their husbands around their neck. [Source: Discover, March 1993 ∩]

After the Napoleonic Wars in the 1820's British settlers began arriving on Tasmania in great numbers. The few Aboriginals that survived the sealers and convicts were hunted from horseback, caught in steel traps and poisoned with tainted flour. Sometimes the testicles of Aboriginal men were cut off so their killers could watch them run around frantically before they died from a loss of blood. Even the police got into the act. On one outing they killed 70 Aboriginals, including many children who had their heads split open like watermelons. ∩

An 1828 law gave white settlers permission to shoot Aboriginal trespassers on sight. A bounty of five pounds per adult and two for children was established not long afterwards. By 1830 the original population of 5,000 Aboriginals had been reduced to 300. In 1833, the British persuaded the approximately 200 surviving Aboriginal Tasmanians to surrender themselves with assurances that they would be protected and provided for, and eventually have their lands returned. This turned out to be no more than a ruse and the Tasmanians were quietly transported to a permanent exile in the Furneaux Islands. A group of six Tasmanians remained at large until 1842. Captured Aboriginals survived for a few more decades. In 1876, the last full-blooded Aboriginal Tasmanian, a woman named Truganini, died sick and brokenhearted.∩

No consensus exists on what caused the Aboriginal Tasmanian population to decline so rapidly to such small numbers. The traditional view, still affirmed, is that they were mostly killed off by introduced diseases. Others argue that the declines were mainly a consequence of wars with white people and between Aboriginal groups and the prostitution of women. [Source: Wikipedia]

Last Pure-Blood Aboriginal Tasmanians

In 1838, the remaining 187 Tasmanians were transported to a nearby island and placed under the control of Anglican missionaries. Forced to wear Western clothes and adopt Western customs, they lost their will to live. Fifty died of pneumonia in one year.

In 1847, the 47 remaining Aboriginals who remained were transported back to the Tasmanian mainland to live in former convicts barracks. Many died there of respiratory illnesses. Truganini, the woman who died in 1876, was the "full-blooded" Aboriginal Tasmanian,

People of mixed European and Aboriginal descent survived in the islands in the Bass Strait between Tasmania and Australia. In recent years they have expanded into Tasmania and Australia. In the 1990s, those groups numbered about 9,000 individuals. Each year many of them gather together to engage in muttonbirding.

All of the Aboriginal Tasmanian languages have been lost; research suggests that the languages spoken on the island belonged to several distinct language families. Some original Tasmanian language words remained in use with Palawa people (a community of people descended from European men and Aboriginal Tasmanian women on the Furneaux Islands off Tasmania, [Source: Wikipedia]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated September 2025