Home | Category: Aboriginals

ABORIGINAL LIFE

Many Aboriginal people receive a monthly allowance in restitution from the Australian government in the same way that Native Americans receive a monthly payment from the United States government. Aboriginal people buy various kinds of goods with this money. Often in rural communities, the majority of the check goes to food in the form of tea, flour, and tinned meat. Some Anglo-Australians visit outstations after the checks are delivered to these communities. They then will set up a type of bank/general store from the back of a utility truck and sell products to the people at extremely inflated prices. [Source: J. Williams, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life”, 2009, Encyclopedia.com]

Redfern was traditionally the Aboriginal ghetto in the Sydney suburbs. An inner southern suburb of Sydney located 3 kilometers (1.9 miles) south of the Sydney central business district, it contained decaying slums where whites were not welcome and drug dealers operates openly. It was the site of the 2004 Redfern riots sparked by the death of Thomas 'TJ' Hickey a teenager who was riding on his bicycle and chased by a police vehicle, resulting on his impalement on a fence. In recent years Redfern has become gentrified and Aboriginals make up only 3.2 percent of Redfern now.

Living in the bush as some Aboriginals do takes some adaptions. Traditionally, to survive in the outback, Aboriginals needed to know the precise location of every water hole within several hundred miles of their home if they wanted to wander in the bush. In really remote places teachers traditionally arrived several times a year to teach in the "school of the bush" and nurses were flown in by small plane to provide medical care. Aboriginal youths sometimes cover their face with mud before swimming in a billibog, or water whole.

RELATED ARTICLES:

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL CUSTOMS, SOCIETY AND RITUALS ioa.factsanddetails.com

TRADITIONAL ABORIGINAL LIFE: FOOD, HOMES, HUNTING ioa.factsanddetails.com

LIFE OF EARLIEST HUMANS IN AUSTRALIA: TOOLS, WEAPONS, ART, SETTLEMENTS ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL MEN AND WOMEN: GENDER, MARRIAGE, SEX ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIAN SEX: PRACTICES, ATTITUDES, ADOLESCENCE ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL RELIGION: TRADITIONAL BELIEFS, DEMOGRAPHY AND DEATH ioa.factsanddetails.com

RITUAL LIFE AND MYTHS OF ANCIENT AUSTRALIANS ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIAN ART ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS (FIRST NATION PEOPLE) OF AUSTRALIA: NAMES, DEMOGRAPHICS, LANGUAGES ioa.factsanddetails.com

EARLY MODERN HUMANS IN AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINALS AT THE TIME EUROPEAN COLONIZATION BEGAN ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIA ABORIGINALS FROM 1900 TO PRESENT: DISCRIMINATION, ASSIMILATION, SOME RESTITUTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIA’S STOLEN GENERATIONS: VICTIMS, LAWS, RATIONALE, OUTRAGE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS IN QUEENSLAND: SOME GROUPS, CUSTOMS, LIFESTYLES ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIANS IN NORTH NORTHERN TERRITORY: SOME GROUPS, CUSTOMS, LIFESTYLE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS OF CENTRAL AUSTRALIA: SOME GROUPS, CUSTOMS, ART, LIFESTYLE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS IN WESTERN AUSTRALIA: SOME GROUPS, HISTORY, CUSTOMS, TRADITIONAL LIFE ioa.factsanddetails.com

Aboriginal Homes

Housing varies between urban and rural Aboriginal people. The national, state, and local governments have encouraged nomadic groups to settle in houses in the European manner, and, to this end, they have built houses for some groups that live in the desert regions of central and western Australia. Aboriginal people have adapted these structures to their own design, using them as a place to store things, but generally regarding them as too small and too hot to actually eat, sleep, or entertain in.[Source: J. Williams, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life”, 2009, Encyclopedia.com]

Contrary to popular belief, not all Aboriginals in the old days were nomadic. Some lived in permanent homes. In western Victoria, they built stone homes. In the desert they used semicircular shelters made from bowed branches covered with leaves and grasses. In Tasmania, some tribes built large conical thatch shelters that could hold up to 30 people.

Some Aboriginals live outdoors in remote government-sponsored communities called outstations. The cinderblock homes provided by the government provide shelter during storms. The soil is often too poor to farm. Many Aboriginals live in shacks with corrugated metal roofs. In some places there is no electricity, telephone or oil and water is collected for cooking. When Cathy Newman of National Geographic asked an old woman what she thought of her shack, she replied "I don't want to live anywhere else. I put trust in my ancestors. This is where they used walkabout in the bush."

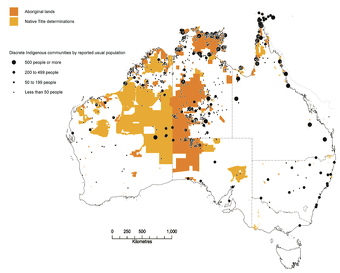

Outstations and Where Rural Aboriginals Live

Rural Aboriginal Australians live in remote communities, small towns, traditional Indigenous lands, and the countryside. While many live in urban area, a significant portion reside in remote parts of the Northern Territory and Western Australia. Over 12,000 Aboriginal people live in over 200 remote communities, primarily in the Kimberley and Pilbara regions of Western Australia. In the Northern Territory a large proportion of the Aboriginal population lives in remote areas on traditional lands such Arnhem Land. Queensland and New South Wales have large Aboriginal populations, some of which are in rural or remote settings.

Some Aboriginal people live on their ancestral lands, practicing their traditional ways of life, which can include hunting, fishing, and gathering bush tucker. Some live in communities located in or near regional towns such Alice Springs.

An outstation, homeland or homeland community is a very small, often remote, permanent community of Aboriginal Australian people connected by kinship, on land that often, but not always, has social, cultural or economic significance to them, as traditional land. The outstation movement or homeland movement refers to the voluntary relocation of Aboriginal people from towns to these locations mainly in the 1970s and 80s.

Individual small communities continue to exist but they are described "settlements" or “homelands” rather “outstations” now. They generally survive on one-off grants for such things as Indigenous business enterprise or environmental protection, private contributions by their residents, or royalties from mineral exploration on their land. As of 2020 there were around 500 homelands in the Northern Territory, which include 2,400 residences housing about 10,000 people. The Northern Territory Government delivers services via its Homelands Program by funding service providers who provide housing maintenance, municipal and essential services. However, there was concern that many remote schools and other services were under-funded.

La Perouse — an Aboriginal Suburb in Sydney

La Perouse is a suburb with a relatively large Aboriginal population in the Eastern Suburbs of Sydney, Located about 14 kilometres (8.7 miles) southeast of the Sydney central business on the La Perouse peninsula is the northern headland of Botany Bay, the area is home to around 1,100 people of which about a third are Aboriginals.

Sarah Newey wrote in The Telegraph: Pointing across Botany Bay’s calm waters, Ivan Simons hones in on a grassy verge just visible amid the trees. The spot marks a key moment for modern-day Australia: the arrival of Captain Cook, and Europe’s “first contact” with the continent’s Indigenous peoples. “When I say where I grew up, people say ‘you were the ones that let Captain Cook in! You’re to blame!’ And we laugh,” says Mr Si standing atop the cliffs which formed the backdrop to his childhood in La Perouse, a coastal suburb home to Sydney’s only Aboriginal reserve. “But in truth it’s been a struggle, generation to generation, to move past the legacy of first contact,” the 73-year-old adds. “Our history has been one of survival.” [Source: Sarah Newey, The Telegraph, October 12, 2023]

In La Perouse – affectionately known as “Lar Per” by locals – elders say that building strong Aboriginal organisations and working in cooperation with the local government has been critical to improving life here. The community – where ex-England rugby coach Eddie Jones went to school – is now thriving, said Mr Si former chair of the local Aboriginal Land Council. “We’re a positive example of working with the local council, and being listened to and trusted by the local council,” said Mr Si flagging initiatives from a strong sports club that keeps children busy, to an Aboriginal-run organisation offering elderly care and lifts to medical appointments.

“The impact of that dispossession – taking land away, taking families away, taking culture away, taking language away – it is still huge,” added Ronald Prince, an Aboriginal cultural engagement officer at La Perouse museum, which chart’s the challenges and successes of the community since Captain Cook first landed across the bay. “But we’re still surviving, we’re still thriving. We’re maintaining our cultural practices and sharing our stories,” he said. “I think Lar Per is an example of what can be achieved.”

Aboriginal Foods

Aboriginals have traditionally lived off the land, taking advantages of different food sources in different places. In some places they foraged for wild onions and bush bananas. In others they, dug up honey ants and witchetty grubs, and hunted emus, kangaroos and possums. Bush tucker found around Alice Springs includes mistletoe berries, bush bananas, bush coconuts (which look more like apples than coconuts).

Lomandra longifolia (spiny-headed mat-rush) is a plant found growing near beaches and many places in southeast Australia. Bundjalung people ground up the seeds from this plant to make flour for baking a flat bread in hot ashes. The long, strong leaves were dried out and used for weaving baskets. Sarah Reid wrote in the BBC: The bread is high in fibre and gluten free. And it tastes good. The Indigenous word for bread varies between language groups, but in English, rustic-style bread cooked in fire is most commonly known as “damper”. It wasn’t long before the term “damper” was immortalised in popular culture by the likes of colonial-era bush poet Banjo Paterson. [Source: Sarah Reid, BBC, March 2, 2021]

Indigenous Australian bread and breadmaking traditions vary according to the place with different plants, techniques and tools traditionally used to extract flour. In the mangroves of Far North Queensland bread was traditionally made by the Kuku Yalanji people used many native seeds and grains such as black bean, black wattle and pandanus seeds. Some people still practice the treatments required to remove toxins in the plants. In the Northern Territory’s Arnhem Land you can still see deep grooves in rocky outcrops made by grinding native grass seeds hundreds — maybe thousands — of years ago.

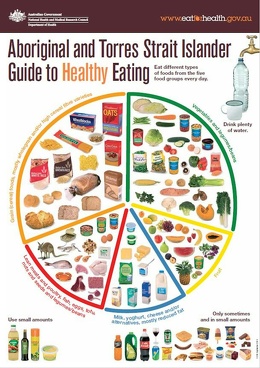

By the early 19th Century, government rations for Indigenous Australians consisted one pound of white flour, two ounces of sugar and half an ounce of tea per day. These highly processed, low-nutrient foods negatively impacted Indigenous health. Today Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are 4.3 times more likely to suffer from Type 2 diabetes than non-Indigenous Australians. [Source: Sarah Reid, BBC, March 2, 2021]

Barbara Santich wrote in the “Encyclopedia of Food and Culture”: Many Aboriginals today have lost touch with their foods and foodways, preferring instead the convenience of Western-style foods. Nevertheless, recognition of the health benefits to Aboriginals of their traditional diet has resulted in active encouragement of hunter-gatherer practices, even if only to supplement store foods. In many areas, Aboriginals have special hunting and fishing rights for species that are otherwise protected or subject to limits—though today their hunting typically involves firearms rather than clubs and spears. [Source: Barbara Santich, “Encyclopedia of Food and Culture”]

See Traditional Foods Under TRADITIONAL ABORIGINAL LIFE ioa.factsanddetails.com

Aboriginal Jobs and Unemployment

Aboriginals also have an unemployment rate has been three to six times higher than the national rate. The Australian aboriginal unemployment rate was 12 percent in 2021, compared to around four percent for Australians as a whole. The Aboriginal unemployment rate was higher for males than females, with regional location and lower levels of educational attainment also correlating with increased unemployment among First Nations people.

In 2000, The official unemployment rate for Aboriginals was 23 percent, but some Aboriginal leaders said the true figure is closer to 51 percent, compared to 6.9 percent for Australians as a whole. Aboriginals in their 20s are four time more likely to be unemployed. In some Aboriginal communities, 80 percent of the residents draw welfare checks.

Australian Aboriginal people work in diverse occupations and industries, with common fields including community and personal services, professionals, technicians and trades workers. In decades past they often worked as stockmen and laborers on white-owned cattle and sheep stations (ranches). In the old days Aboriginals traded goods using trade routes that crisscrossed the continent. Some of the most sought after items were certain types of stones and shells that had ritual significance. Ocher and boomerangs were important trading goods. Aboriginals also engaged in "exchange ceremonies," where only songs and dances were exchanged.

In traditional Aboriginal societies there was a division of labor according to age and sex. Women and children were responsible for gathering vegetables, fruit, and small game such as goannas (a large lizard). Men were responsible for obtaining meat by hunting both large and small game. Men in Aranda society hunted with a variety of implements including spears, spear throwers, and non-returning boomerangs. Aboriginal people in urban areas are employed in a variety of jobs. However, gaining employment is often difficult due to discrimination. [Source: J. Williams, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life”, 2009, Encyclopedia.com]

Disadvantaged Aboriginals and Poor Health

Australia’s Aboriginals make are consistently the nation’s most disadvantaged group, with far higher rates of unemployment, alcohol and drug abuse, and domestic violence than the general population. In the 2000s, Aboriginal male life expectancy was 59.4 years, compared with 77 years for all males. For indigenous women, life expectancy was 64.8 years compared with 82.4 years for other Australian women. [Source: Michael Perry, Reuters, May 24, 2007]

Reuters reported: The Australian Medical Association, which represents the nation’s doctors, says institutionalized racism is preventing Aboriginals gaining proper health care and shortening their lives. The majority of Aboriginals do not live in cities but in isolated communities, often in the outback, with limited access to health care, educational services and employment.

Aboriginals in Western Australia have one the highest infant mortality rates in the world (18 deaths per 1,000 in the 2000s). There are high rates of diabetes, heart disease and kidney disease. Alcohol abuse is one of the remain factors in the Aboriginals' poor health. A doctor in Coober Pedy told the New York Times, "I can clean out the head wounds and look after the diabetes and blood pressure and when they overdose on something but how to get beyond that and into the preventative area so they don't have to come to the doctor, that's a much more difficult situation. You've got to change the mentality of the people and give them some purpose to exist."

Dr Glenn Harrison, Australia’s first Indigenous emergency physician, told The Telegraph many of the stark inequalities in health nationwide stem from a lack of understanding of Aboriginal culture among doctors; an uneasiness of hospitals among Indigenous people, who associate them with death; and the sheer distances involved to reach some communities. Conditions including lung cancer, diabetes and cardiovascular disease are all major problems – and while improvements are being made, they’re not enough to ‘close the gap’. [Source: Sarah Newey, The Telegraph, October 12, 2023]

In parts of the country, rheumatic heart disease also persists – a potentially deadly condition that predominantly affects children and teenagers. As of December 2021, it was a condition affecting almost 10,000 people.“That’s a third world disease, but it’s endemic in some of the northern parts of Australia,” says Dr Harrison. “That’s because of overcrowding and poor access to clean and safe water and hygiene services, which is a terrible situation to have in a country that’s rich and has great health services as Australia’s.”

Alcohol and Aboriginals

Before colonization, Aboriginal Australians fermented various native plants and tree saps to create alcoholic drinks, including mangaitch from Banksia cones, way-a-linah from Eucalyptus sap, and kambuda from Pandanus nuts. These drinks were weaker than modern spirits and were accompanied by traditional controls and customs. Until the late 1960s, Indigenous Australians were legally prohibited from purchasing alcohol. In 1990 Aboriginals enjoy drinking beer and Ripple-like Coolabah Moselle. When they were low on the money they’d mix methylated spirits and milk into a concoction called a "white lady."

Describing a drunken Aboriginal football game, Cathy Newman wrote in National Geographic, "Twenty-six football players. Five hundred drunk spectators. A woman spins wildly, hands overheard, in the middle of the scrimmage while referees try to shoo her off. The game ends in an all-out brawl among the Aboriginals, and police dogs are brought in.

In the Aboriginal reserve of Kowanyama on the 1990s it was estimated that alcohol sales accounted for one third of all the money spent in the community. The sales in the local canteen could add up to $50,000 a week and a guard was sometimes hired to keep order. A ruling passed in 1980s limited the amount of beer sales to five cans of beer per person per day except on Fridays when they could they buy six.

When the canteen that sold alcohol in the Aurukun community in Cape York Peninsula was closed, Aboriginals established a "sly grog" business in which a plane was rented for $230 to fly to the mining town of Weipa where ten cases of beer bought for $230 could be sold back in Aurukun for $760 (making a profit of $350).

Alcoholism and Aboriginals

Aboriginal Australians drink less alcohol overall than the general Australia population but are are more likely to consume it at dangerous levels, leading to higher rates of alcoholism and alcohol-related hospitalisation, disease, and death. Alcohol abuse by Aboriginals is more of a problem in some areas than others and certain demographics, mostly men. Alcohol-related problems have been linked to the intergenerational trauma, poverty, social exclusion, and lack of access to services stemming from colonisation and ongoing discrimination.

Aboriginals have the highest rates of alcohol abuse in Australia. A government sponsored report on alcoholism in the 1990s reported that Aboriginals drink less than white Australians but they were more affected and had a higher death rate as a result of it. One Queenslander told Theroux, that many white Australians become aggressive when they get drunk "but most of the Abos just drink and fall down.[Source: "The Happy Isles of Oceania" by Paul Theroux, Ballantine Books ∝]

Alcohol-related illnesses are one of the most common forms of death in Aboriginal communities. Overdrinking is at the root of other social problems such as domestic violence juvenile deliquancy, infant mortality

Alcohol-related issues are a particularly big problem in the Northern Territories. A 2017 review found that people there had the highest per capita rate of alcohol consumption in the world. The Northern Territory's frontline services deal with thousands of alcohol-related assaults each year, the country's highest rates of domestic violence and a number of intergenerational problems like fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. Aboriginal alcohol abuse was a particularly big problem in the Alice Springs area

Campaigns Against Alcoholism in Aboriginal Communities

As part of an efforts to tackle the alcohol problem among Aboriginals, many Aboriginal communities have abandoned alcohol and become dry. Rehabilitation programs have been set up for alcoholics. Women are very active in these problems, partly because they are the victims of alcohol-induced domestic violence. At part of the 1986 "beat the Grog" campaign, many Aboriginal communities and missions banned the sale of alcohol and set up alcohol rehabilitation facilities.

In September 2007, the Australian government banned alcohol in the Northern Territory Aboriginal communities, town camps, and Indigenous land areas as part of the Northern Territory Emergency Response (NTER) (the "Intervention") to address child abuse and domestic violence. There There were penalties for possessing, transporting, or drinking alcohol in these areas. These measures were intended to stop the "flow of alcohol" that was destroying communities and putting children at risk. The alcohol bans were a key component of the larger Northern Territory Intervention (NTER) — government measures enforced from 2007 to 2012 that also included changes to welfare payments, such as income management, and reforms to the management of education, employment, and health services in affected communities. The NTER-era bans lasted until 2012, after which they continued under the Stronger Futures legislation. In 2022, the NT government allowed communities to "opt-in" to continuing the bans.

In 2023, following a rise in alcohol-related crime, the Northern Territories government reinstated bans in some areas, notably Alice Springs. The Guardian reported: There were immediate restrictions on alcohol sales and more than A$50 million worth of community support to restore order and safety to the central Australian town of Alice Springs, where alcohol-related harms, violent crime and unrest have reached extreme levels. According to the terms of the ban there were takeaway alcohol-free days on Monday and Tuesday and alcohol-reduced hours on other days, with takeaways allowed between 3pm and 7pm and a limit of one transaction per person each day, said Northern Territories chief minister, Natasha Fyles. [Source: Lorena Allam The Guardian, January 24, 2023]

Intervention-era bans on alcohol in remote Aboriginal communities came to an end in July, when liquor became legal in some communities for the first time in 15 years and others were able to buy takeaway alcohol without restrictions. Since then, NT police statistics show that reported property offences have jumped by almost 60 percent over the past 12 months, while assaults increased by 38 percent and domestic violence assaults were up 48 percent. “We’re seeing women being beaten on the streets in front of our faces. We’re seeing the trauma that was there come back again,” chief medical officer, Dr John Boffa, said.

Illegal Drugs and Petrol Sniffing by Aboriginals

Drug use is high among Aboriginals. Petrol- and glue-sniffing are the most serious problems. Aboriginals also use marijuana and abuse heroin and other opiates. More expensive cocaine is more of a white people party drig. Aboriginals have the highest rates of drug abuse in Australia. Fuel-sniffing is such a problem that one Queensland Aboriginal leader told AP, "crying infants are silenced with petroleum-drenched rags on their faces.

Petrol (gasoline) sniffing was a major problem in Aboriginal communities in Queensland, Western Australia and the Northern Territories and not restricted to Aboriginal youth. It destroyed health and families but doesn't seem to be such an issue any more. The introduction of a "non-sniffable" petrol variety greatly reduced, but not ended sniffing. Some addicts changed to glue, seen by many as even more dangerous.

Jens Korff wrote in Creative Spirits: Petrol sniffing claimed over 100 Aboriginal lives from 1981 to 2003 across Australia . The practice was first observed in 1951, and is rumoured to have been introduced by US servicemen stationed in the nation's Top End during World War II . Of the Aboriginal population in 1994, 4 percent had tried petrol-sniffing but only 0.3 percent practised it at that time. In 2005 there were some 700 petrol sniffers across central Australia , with the addiction linked to as many as 60 Aboriginal deaths in the NT between 2000 and 2006, and 121 deaths between 1980 and 1987. [Source: Jens Korff, Creative Spirits, August 12, 2020]

The number of petrol sniffers in the Central Desert region dropped from 500 to fewer than 20 after legislation introduced in 2005 gave police powers to confiscate petrol and take sniffers to a place of safety . The general age range of users is from 10-19 years with a mean of 12-15 years, but use by children younger than 10 is not uncommon.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Culture Shock! Australia, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated September 2025