Home | Category: Aboriginals

TRADITIONAL ABORIGINAL LIFESTYLE

At the time that Europeans arrived in Australia, Aboriginals were essentially semi-nomadic hunter-gatherers who lived in tribes made of extended family groups or clans, with clan members believed to have descended from a common ancestral beings. Tribal and clan bonds remain strong today.

Some tribes were largely nomadic. Others were more settled. Aboriginals didn't practice agriculture or raise livestock in the European sense. Instead they collected tubers and other foods and hunted wild animals. Different tribes ate different things and had different food gathering techniques. Some groups practiced Fire-stick farming, also known as cool burning, in which fire was regularly used to burn vegetation. One benefit of this as a management technique was that it promoted the growth of certain edible plants.

Aboriginal customs, beliefs and practices were often finely tuned to their environment. The degree of nomadicism was largely dependent on the amount of food available. Aboriginals often migrated according to the season, taking advantage of food sources available in certain places at certain times of the year. They also observed how animals behaved and where they went to find food.

Fison and Howitt wrote in that the organization of Kaurna society involved independent family groups working and traveling a specified territory known as a pangkarra; these territories were grouped into larger units called yerta—meaning earth, land, or country and derived from words meaning earth and mouth, so that the overriding concept portrayed by the term is one of an area that can sustain the group. [Source: “Marriage Customs of the World From Henna to Honeymoons”: “ by George P. Monger, 2004 ^]

RELATED ARTICLES:

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL CUSTOMS, SOCIETY AND RITUALS ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL LIFE: WHERE THEY LIVE, WORK, DIET, HEALTH, ALCOHOL ioa.factsanddetails.com

LIFE OF EARLIEST HUMANS IN AUSTRALIA: TOOLS, WEAPONS, ART, SETTLEMENTS ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL MEN AND WOMEN: GENDER, MARRIAGE, SEX ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIAN SEX: PRACTICES, ATTITUDES, ADOLESCENCE ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL RELIGION: TRADITIONAL BELIEFS, DEMOGRAPHY AND DEATH ioa.factsanddetails.com

RITUAL LIFE AND MYTHS OF ANCIENT AUSTRALIANS ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIAN ART ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS (FIRST NATION PEOPLE) OF AUSTRALIA: NAMES, DEMOGRAPHICS, LANGUAGES ioa.factsanddetails.com

EARLY MODERN HUMANS IN AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINALS AT THE TIME EUROPEAN COLONIZATION BEGAN ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIA ABORIGINALS FROM 1900 TO PRESENT: DISCRIMINATION, ASSIMILATION, SOME RESTITUTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIA’S STOLEN GENERATIONS: VICTIMS, LAWS, RATIONALE, OUTRAGE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS IN QUEENSLAND: SOME GROUPS, CUSTOMS, LIFESTYLES ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIANS IN NORTH NORTHERN TERRITORY: SOME GROUPS, CUSTOMS, LIFESTYLE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS OF CENTRAL AUSTRALIA: SOME GROUPS, CUSTOMS, ART, LIFESTYLE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINALS IN WESTERN AUSTRALIA: SOME GROUPS, HISTORY, CUSTOMS, TRADITIONAL LIFE ioa.factsanddetails.com

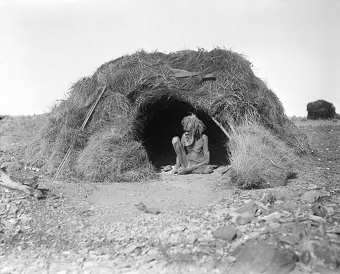

Traditional Aboriginal Homes, Possessions and Boomerangs

Contrary to popular belief, not all Aboriginals in the old days were nomadic. Some lived in permanent homes. In western Victoria, they built stone homes. In the desert they used semicircular shelters made from bowed branches covered with leaves and grasses. In Tasmania, some tribes built large conical thatch shelters that could hold up to 30 people.

Traditional possessions included boomerangs, stone tools, spears; digging sticks, dilly bags (carry bags) and coolamans (wooden carrying dishes), masks, dancing sticks, fishing spears and didgeridoos. The oldest known boomerang is a 30,000-year-old specimen carved from a mammoth bone found in Poland.

Hut of the Eastern Arrernte people covered in porcupine grass, , Arltunga district, Northern Territory, 1920

The four boomerangs and a shaped fragment of one were found in December 2017 and January 2018, when they were exposed in a riverbed during an especially hot summer. Live Science reported: A study into five rare "non-returning" boomerangs found in a dry riverbed in South Australia revealed they were probably used by the Aboriginals to hunt waterbirds hundreds of years ago. Radiocarbon dating revealed that Aboriginals crafted the boomerangs from wood between 1650 and 1830 — before the first Europeans explored the area. In addition to hunting, researchers also suspect the boomerangs could have been used to dig, stoke fires and perform ceremonies, as well as be used in hand-to-hand combat. [Source: Live Science]

Because Aboriginal boomerangs are made from wood, they quickly decompose when exposed to the air. This is only the sixth time that any have been found in their archaeological context. "It's especially rare to have a number of them found at once like this," Amy Roberts, an archaeologist and anthropologist at Flinders University in Adelaide, told Live Science.

Eric A. Powell wrote in Archaeology magazine: While on survey in a national park in southern Australia in the mid 2010s, archaeologists discovered a male skeleton eroding out of a riverbank. Dubbed Kaakutja, or “older brother” in a local language, the man had a fatal six-inch gash in his skull. When Griffith University paleoanthropologist Michael Westaway first examined the skull damage, he thought “it looked similar to steel-edged weapon trauma from medieval battles.” But radiocarbon dating of Kaakutja’s skeleton shows he died in the thirteenth century, well before Europeans reached Australia and introduced metal to the continent. Westaway concluded that the wound was likely caused by a heavy war boomerang or a sharp-edged club known as a lil-lil, both of which are depicted in Aboriginal rock art. “Kaakutja’s trauma is unique in that it is the first recorded case of edged-weapon trauma in Australia,” he says. The lack of defensive wounds to the man’s arms suggests he may have been attacked while he slept, which, according to nineteenth-century ethnographic accounts, may have been a common tactic in prehistoric Australian conflicts. [Source: Eric A. Powell, Archaeology magazine, January-February 2017]

Traditional Aboriginal Food

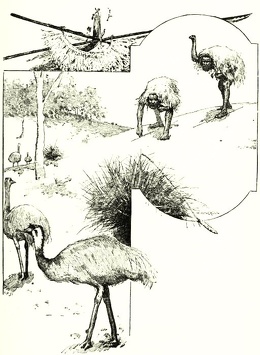

Aboriginals have traditionally lived off the land, taking advantages of different food sources in different places. In some places they foraged for wild onions and bush bananas. In others they, dug up honey ants and witchetty grubs, and hunted emus, kangaroos and possums. Bush tucker found around Alice Springs includes mistletoe berries, bush bananas, bush coconuts (which look more like apples than coconuts). Honey ants look like golden globes. They are dug out of the ground of with a stick. Micheal Parfit write in National Geographic, "With trepidation I sucked in the globe. It burst into my mouth, sweet and tangy...They're sweet with a gritty zing."

Typical Aboriginal Foods: Kangaroo, Emu, Witchetty Grubs, Lizards, Snakes, Moths, Berries, Roots, Nectars, Shellfish, Wallaby

Since many Aboriginal groups were nomadic hunters and gatherers, they did little in the area of food preparation. Meals were simple. Almost all Aboriginal groups made a conceptual distinction between meat and non-meat foodstuffs. This is reflected in the terminology of the various languages. In Walpiri, the term kuyu refers to meat or any game animal or bird that is killed for meat. In contrast, the term miyi refers to vegetables or fruit. [Source: J. Williams, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life”, 2009, Encyclopedia.com]

In the wetter northern and eastern parts of Australia, Aboriginals grew yams and caught fish in traps hundreds of meters long. Today people there still hunt for crocodile eggs. In Victoria, Aboriginals trapped migrating eels in permanent stone weirs several kilometers long. Aborigines in western Australia make a sweet drinks from a red honey-suckle flower. Explorer Ludwig Lecichardt reported in the 19th century that he was fed bark bowls "full of honey water, from one of which I took a hearty draught, and left a brass button."

When special occasions such as initiation brought large numbers of Aboriginals together, it was essential that food resources in the vicinity of the meeting place were both adequate and reliable. Ceremonial foods, therefore, were less associated with particular qualities than with seasonal abundance. In the mountainous regions of southern New South Wales and Victoria, bogong moths (Agrotis infusa ) were profuse and easy to collect in late spring and summer, and at this time Aboriginal groups converged in the mountains where ceremonies took place. The prevalence of shell middens suggests that shellfish provided ceremonial sustenance in coastal areas. In Arnhem Land (Northern Territory) cycad nuts were plentiful at the end of the dry season, when travel was still possible, and the kernels, once heated to remove toxins, were ground to yield a thick paste, and subsequently baked in the ashes to serve as a special ceremonial food for men participating in sacred ceremonies and forbidden to women and children unless authorized by older men. [Source: Barbara Santich, “Encyclopedia of Food and Culture”]

According to Archaeology magazine: In some cultures, insects are an important dietary source of protein, fat, and vitamins. Europeans who first settled Australia in the 19th century recorded how Aboriginal groups gathered annually in the Australian Alps to collect large numbers of migratory bogong moths. Moth residue on a recently excavated grinding tool from Cloggs Cave shows that this practice dates back at least 2,000 years. Researchers believe the tool was used to process the insects into cakes that could be smoked and preserved for weeks. [Source: Archaeology magazine, May 2021]

Aboriginal Hunter-Gathering

Barbara Santich wrote in the “Encyclopedia of Food and Culture”: Aborigines practiced a highly mobile hunter-gatherer lifestyle, moving frequently from place to place in accordance with seasonal availabilities of food resources. At the same time, they manipulated the environment in such a way as to favor certain species of flora and fauna. Their management of the land and its resources included setting light to dry grass and undergrowth in specific areas at certain times of the year in order to drive out small animals that they could easily capture. This practice has since been termed "firestick farming." It had a secondary benefit in that the new green growth which followed rain attracted small marsupials and other animals to the area, thus ensuring food supplies. [Source: Barbara Santich, “Encyclopedia of Food and Culture”]

Typically, men hunted large game such as kangaroos and emus, and speared, snared, or otherwise procured smaller animals (opossums, bandicoots), birds (wild ducks, swans, pigeons, geese), and fish. Men tended to operate individually, while groups of women and older children collected plant foods (fruits, nuts, tubers, seeds), small game such as lizards and frogs, and shellfish. There were variations to this pattern; around coastal Sydney, the principal food-gathering task of women was fishing, and men also collected vegetables. The relative contributions of men and women to the communal meal varied according to season and location, but women's gathering activities could provide from 50 to 80 percent of a group's food. The time taken to collect a day's food varied similarly, but rarely would it have occupied the whole day.

The Aboriginal diet was far from monotonous, with a very wide range of food resources exploited. In northern Australia, thirty different species of shellfish were collected throughout the year from seashore and mudflats; in Victoria, about nine hundred different plant species were used for food. Whatever the available resources, Aboriginals did not always and necessarily eat everything that was edible; in some coastal regions fish and sea animals were preferred as sources of protein, and land animals were relatively neglected. On the other hand, Tasmanian Aboriginals ate lobsters, oysters, and other shellfish but did not eat scaly fish; they avoided carnivorous animals and the monotremes platypus and echidna, though in other regions echidnas were eaten.

Tools were basic: a digging stick for women, spear and spear thrower for men. Fish, birds, and small game could be caught in woven nets or in conical basket traps. Many Aboriginal groups used lines, with crude shell or wooden hooks, to catch fish; alternatively, fish traps were sometimes constructed in rivers and along the coast to entrap fish, or temporary poisons were placed in water-holes to stun fish or bring them to the surface.

Traditional Aboriginal Food Preparation

Barbara Santich wrote in the “Encyclopedia of Food and Culture”: Many fruits and nuts and a few plant foods could be eaten raw and did not require cooking, but generally roots, bulbs, and tubers were roasted in hot ashes or hot sand. Some required more or less lengthy preparations to improve their digestibility or, in some cases, to remove bitterness or leach out quasi-poisonous components. In the central Australian desert, Aboriginals relish the honey sucked from the distended bellies of underground worker ants; in effect, these "honey ants" serve as live food stores for other worker ants. [Source: Barbara Santich, “Encyclopedia of Food and Culture”]

The principal means of removing toxins were pounding, soaking, and roasting, or a combination of any of these. One particular variety of yam, Dioscorea bulbifera, was subjected to a series of treatments to remove bitterness. First it was scorched to shrivel the skin, which was removed; then it was sliced and the slices coated with wet ashes and baked in a ground oven for twelve hours or more, and the ashes were then washed off before eating.

The kernels of the cycad palm (Cycas armstrongii ), highly toxic in their unprocessed state, were treated by pounding, soaking in still or running water until fermented, and pounding again between stones to produce a thick paste that was cooked in hot ashes, sometimes wrapped in paperbark, yielding a kind of damper or bread.

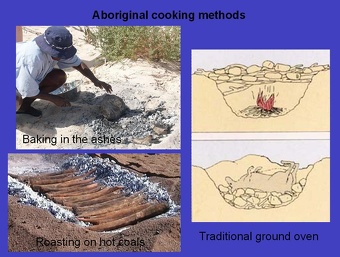

Traditional Aboriginal Cooking

Barbara Santich wrote in the “Encyclopedia of Food and Culture”: Aborigines did not have sophisticated cooking equipment; basic culinary techniques included baking in hot ashes, steaming in an earth oven, or roasting on hot coals, this last method typically used for fish, crabs, small turtles, and reptiles. Oysters, too, were often cooked on hot coals until they opened, but in northern Australia large bivalves were "cooked" by lighting a quick fire on top of the closely packed shells arranged on clean sand, hinge side uppermost. [Source: Barbara Santich, “Encyclopedia of Food and Culture”]

Cooking in hot ashes was the most common method of preparing tubers, roots, and similar plant products including yams (Dioscorea spp.) and the onion-shaped tubers of spike rush (Eleocharis spp.), both of which were important foods for Aboriginals in northern Australia. Witchetty grubs (Xyleutes spp.) and similar grubs from other trees were also cooked in hot ashes, if not eaten raw, as were the flat cakes, commonly called dampers, made from the seeds of wild grasses such as native millet (Panicum sp.). The relatively complicated preparation involved threshing, winnowing, grinding (using smooth stones), the addition of water to make a paste, then baking in the ashes. Seeds of other plants, such as wattles (Acacia spp.), pigweed (Portulaca spp.), and saltbush (Atriplex spp.), as well as the spores of nardoo (Marsilea drummondii ), were treated similarly.

Earth ovens were essentially pits, sometimes lined with paperbark or gum leaves, heated with coals or large stones previously heated in a fire. Foods to be cooked were placed in the oven, covered with more paperbark, grass, or leaves and sometimes more hot stones, then enclosed with earth or sand. Roots and tubers were sometimes placed in rush baskets for cooking in an earth oven, and when clay was available, such as near the edge of a river, fish were enclosed in clay before baking.

Large game such as kangaroo and emu was gutted immediately after killing and carried back to camp where the carcass was thrown onto a fire for singeing. After the flesh had been scraped clean, the animal was placed in a pit in which a fire had previously been lit to supply hot coals, covered with more hot coals plus earth or ash or sand, and baked. The cooking time depended on how long hungry people were willing to wait.

Traditional Aboriginal Hunting

Aboriginals hunted — and still hunt — kangaroos, emu and other animals and birds for food but consider it waste to kill something for no reason. An Australian friend of mine once told me she was driving with some Aboriginals when their car hit a "goanna," a kind of lizard. Even though they were in hurry to get somewhere they stopped, made a fire and ate the goanna before the resumed their journey.

Traditional Aboriginal hunting techniques varied from tribe to tribe, region to region and depended on the prey. Dingoes were domesticated by Aboriginals, primarily as hunting animals. The main hunting instruments were spears, clubs and boomerangs. Aboriginals hunted by beating bushes to drive out game. They ambushed kangaroos at water holes and roasted their meat over open fires. In the tablelands of Queensland, finely woven nets were used to catch wallabies and kangaroos.

Aboriginals used clubs and crowbar-like digging tools for hunting goannas and echidnas. First use thed crowbar tool to dig up the animals in their dens and then whacked them over head with the club. Sometimes Aboriginals skinned their prey and ate the meat raw. Other times they threw it onto a fire and ate it when it was charred and about ready to explode out of its skin. [Source: "The Happy Isles of Oceania" by Paul Theroux, Ballantine Books]

Aboriginal Fire Hunting

In the old days, Aboriginals often hunted by selectively burning dead grass and undergrowth in the forest and encourage he growth of new shoots, which attracted animals that could be hunted and also provided food for the Aboriginals themselves. This practic has been called "fire-stick farming" — the process of clear land with fire to "rejuvenate the land for hunting and gathering.

Abraham Rinquist wrote in Listverse: The Martu people of Australia’s Western Desert are known for using fire to hunt lizards. The result has actually benefited the wildlife of the Outback. The technique creates a small patchwork of cleared land—perfect habitat for bush critters. [Source: Abraham Rinquist, Listverse, September 16, 2016]

Goanna are the Martu’s most valuable resource. These burrowing lizards make up 40 percent of their caloric intake. The Martu technique of goanna hunting is thousands of years old. In winter, the lizards hibernate. Women cover burrow entrances and set the surrounding grass ablaze. Without this technique, the brush becomes overgrown. Unchecked growth is perfect fodder for lightning fires, which can be devastating to mammalian habitat. The practice is such an integral part of Martu culture that their language has a word for every stage of the post fire vegetation growth.

Positively Impact of Aboriginal Hunters in Western Australia Desert Wildlife

The absence of direct human activity on the landscape may be the cause of the extinctions of some mammals in Western Australia according to a Penn State anthropologist Rebecca Bliege Bird. "I was motivated by the mystery that has occurred in the last 50 years in Australia," she said. "The extinction of small-bodied mammals does not follow the same pattern we usually see with people changing the landscape and animals disappearing."

According to a Penn State press release: Australia's Western Desert, where Bird and her team work, is the homeland of the Martu, the traditional owners of a large region of the Little and Great Sandy Desert. During the mid-20th century, many Martu groups were first contacted in the process of establishing a missile testing range and resettled in missions and pastoral stations beyond their desert home. [Source: Penn State news release, February 17, 2019]

During their hiatus from the land, many native animals went extinct. In the 1980s, many families returned to the desert to reestablish their land rights. They returned to livelihoods centered around hunting and gathering. Today, in a hybrid economy of commercial and customary resources, many Martu continue their traditional subsistence and burning practices in support of cultural commitments to their country.

Twenty-eight Australian endemic land mammal species have become extinct since European settlement. Local extinctions of mammals include the burrowing bettong and the banded hare wallaby, both of which were ubiquitous in the desert before the indigenous exodus, Bird told attendees at the 2019 annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science February 17, 2019 in Washington, D.C. "During the pre-1950, pre-contact period, Martu had more generalized diets than any animal species in the region," said Bird. "When people returned, they were still the most generalized, but many plant and animal species were dropped from the diet."

She also notes that prior to European settlement, the dingo, a native Australian dog, was part of Martu life. The patchy landscape created by Martu hunting fires may have been important for dingo survival. Without people, the dingo did not flourish and could not exclude populations of smaller invasive predators — cats and foxes — that threatened to consume all the native wildlife.

Bird and her team looked at the food webs — interactions of who eats what and who feeds whom, including humans — for the pre-contact and for the post-evacuation years. Comparisons of these webs show that the absence of indigenous hunters in the web makes it easier for invasive species to infiltrate the area and for some native animals to become endangered or extinct. This is most likely linked to the importance of traditional landscape burning practices, said Bird.

Indigenous Australians in the arid center of the continent often use fire to facilitate their hunting success. Much of Australia's arid center is dominated by a hummock grass called spinifex. In areas where Martu hunt more actively, hunting fires increase the patchiness of vegetation at different stages of regrowth, and buffer the spread of wildfires. Spinifex grasslands where Martu do not often hunt, exhibit a fire regime with much larger fires. Under an indigenous fire regime, the patchiness of the landscape boosts populations of native species such as dingo, monitor lizard and kangaroo, even after accounting for mortality due to hunting. "The absence of humans creates big holes in the network," said Bird. "Invading becomes easier for invasive species and it becomes easier for them to cause extinctions."

Aboriginal Dugong and Sea Turtle Hunting

Aboriginal peoples in Australia, particularly in Torres Strait and the Wellesley Islands, have hunted dugongs for thousands of years for meat and oil, but the practice is now heavily regulated due to the species' vulnerable status. Historically, dugong hunting involved netting or spearing from rafts. Modern methods include spearing from dinghies with outboard motors, using a harpoon with a detachable head. Traditional knowledge guides sustainable practices, such as conserving pregnant females and ensuring the long-term stability of the dugong population, although poaching remains a concern.

Indigenous peoples of the Torres Strait have harvested dugongs for at least 4,000 years, with evidence of substantial harvesting over the last few centuries. Dugongs hold deep cultural importance, featuring prominently in Aboriginal stories and daily life in the Torres Strait, symbolizing a connection between people and the marine environment.

Dugongs are listed as vulnerable to extinction, and their populations in regions like the Great Barrier Reef are dwindling. About 10,000 dugongs remain in Australian waters. The Aboriginals are allowed to take 100 of them a year. The hunting is allowed is regulated, and some hunters voluntarily avoid killing pregnant dugongs as a conservation measure. Monitoring and Management: Research, including aerial surveys, helps monitor dugong populations and assess the sustainability of the traditional harvest. An illegal meat trade poses a threat, with some individuals disregarding regulations and engaging in "rogue" hunting. Pollution and climate change negatively impact the seagrass habitats essential for dugong survival.

Guugu Yimithirr Aboriginals on the northern tip of the Cape York Peninsula still hunted dugongs in the 1990s. To kill one, the Aboriginals speared it with a harpoon and then held it against the boat until it drowned. The oil was used relieve aches and the meat they said was very tasty. The Guugu Yimithirr Aboriginals also hunted sea turtles. When a turtle was caught in the old days the Aboriginals used to eat the whole thing, in the 1990s they took the choicest meat and left the rest for the feral pigs. Only Aboriginal are allowed to catch turtles on Thursday Island. A Cypriot explained how he went about hunting the animal there: "We just take a black bloke with us and that makes it legal." [Source: "The Happy Isles of Oceania" by Paul Theroux, Ballantine Books ∝]

Aborigines hunt stingrays with spears. During the 1930's Aboriginals in northern Queensland earned money by selling sea cucumbers and sea slugs to the Chinese at a time when that country was experiencing a shortage of those creatures. They also exported trochus shells, one of materials used to make buttons before plastic was invented.∝

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Culture Shock! Australia, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated September 2025