Home | Category: Animals / Kangaroos, Wallabies and Their Relatives

KANGAROOS

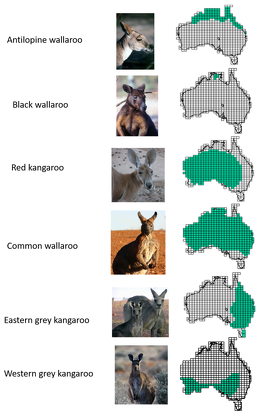

Some kangaroo, wallaby and wallaroo species: 47) Eastern Grey Kangaroo (Macropus giganteus), 48) Western Grey Kangaroo (Macropus fuliginosus), 49) Red Kangaroo (Osphranter rufus), 50) Black Wallaroo (Osphranter bernardus), 51) Antilopine Wallaroo (Osphranter antilopinus), 52) Common Wallaroo (Osphranter robustus), 53) Whip-tailed Wallaby (Notamacropus parryi), 54) Agile Wallaby (Notamacropus agilis), 55) Red-necked Wallaby (Notamacropus rufogriseus), 56) Western Brush Wallaby (Notamacropus irma), 57) Black-striped Wallaby (Notamacropus dorsalis), 58) Tammar Wallaby (Notamacropus eugenii), 59) Parma Wallaby (Notamacropus parma)

Kangaroos are the world's largest marsupials and are members of the family Macropodidae (macropods). The term kangaroo is usually used to describe the largest species from this family — red kangaroos, antilopine kangaroos, eastern grey kangaroos, and western grey kangaroos. The aforementioned kangaroos are indigenous to Australia. Other macropod, including tree kangaroo live New Guinea.

A male kangaroo is called a buck or a boomer. A female is called a doe or a flyer. Young are called joeys. A group is called a mob, troop or herd. Red kangaroos are the largest of all kangaroos. Full grown boomers may weigh over 90 kilograms 200 pounds and stand over two meters (seven feet) tall. The smallest are one-pound musky rat kangaroos.

Kangaroos have adapted to nearly every habitat in Australia, says zoologist Tim Flannery, “from underground burrows to the treetops of tropical forests...So breathtakingly different is the kangaroo that if it did not exist, we’d be unable to imagine it.” To Flannery, kangaroos are “the most remarkable animals that ever lived, and the truest expression of my country … because they have been made by Australia. They are, in short, the continent’s most successful evolutionary product.” [Source: Jeremy Berlin, National Geographic, February 2019]

In 2008, scientists finished sequencing genome of a macropod (kangaroo, wallaby). The project was jointly funded by the Victorian Government and the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) and was led by Professor Jenny Graves. The tammar wallaby (Macropus eugenii), was the model kangaroo used for the genome mapping. Like the o'possum, there are about 20,000 genes in the kangaroo's genome, Graves says. That makes it about the same size as the human genome, but the genes are arranged in a smaller number of larger chromosomes. "Essentially it's the same houses on a street being rearranged somewhat," Graves says. "In fact there are great chunks of the [human] genome sitting right there in the kangaroo genome." [Source: Dani Cooper, ABC, November 18, 2008]

Book: “Chasing Kangaroos” by Tim Flannery (Grove)

Macropods — the Kangaroo, Wallaby Group

Macropodidae (macropods) is the family of animals that includes kangaroos, wallabies, wallaroos, tree-kangaroos, pademelons, quokkas, and several other groups. Macropod is Latin for big feet. Depending on which scientist you talk to there are roughly between 50 and 100 species of macropods, sometimes called hoppers. The large discrepancy in the number of species revolves around whether or not bettongs, potoroos and ground-dwelling rat kangaroos are true macropods. Most scientists recognize 68 species as listed in the in The Third edition of Wilson & Reeder's Mammal Species of the World (2005).

Kangaroos, wallabies and wallaroos are marsupials. They were first grouped with rodents and later placed in the same family with possums. It was only within the last few decades that they were given their own group —Macropodidae (macropods).They should not be confused with kangaroo rats, jerboas and other similar jumping rodents found in America, Asia and Africa.

Macropodidae is the second largest family of marsupials (after Didelphidae), with 12 genera. Macropods (also called macropodids) are found in Australia, New Guinea, and on some nearby islands. There are species that fit into almost every habitats found in those places: scrubland, deserts, bush, swamps, rocky ledges, plains, tropical rainforests and temperate forests.

Macropodids are herbivores (animals that primarily eat plants or plants parts). They can be grazers (primarily eat grass or other low-growing plants) or browsers (primarily eats non-grass plants such as bushes and tree parts higher up off the ground) or both. They have a complex sacculated stomach, and the compartments serve as sites for fermentation (digestion) by microorganisms. Some species even regurgitate food for additional chewing like a cow. Most macropods are nocturnal (active at night),, while a few are diurnal (active during the daytime), or crepuscular (active at dawn and dusk). [Source: Phil Myers, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Macropods have a well developed pouch that opens at the front of their body. Their reproductive cycle includes a period of embryonic diapause (temporary suspension of implantation and development of the embryo). At times, females of most species may support young of three litters — one in the uterus, one residing full-time in the pouch and attached to a nipple, and the third living out of the pouch but returning to nurse. |=|

RELATED ARTICLES:

MARSUPIALS: HISTORY, EVOLUTION, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

MARSUPIALS IN AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

MARSUPIALS IN AUSTRALASIA (AUSTRALIA, NEW GUINEA, NEARBY ISLANDS) ioa.factsanddetails.com

KANGAROO BEHAVIOR: FEEDING, REPRODUCTION, JOEYS ioa.factsanddetails.com

RED KANGAROOS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

GREY KANGAROOS: EASTERN, WESTERN, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

KANGAROOS HOPPING: MOVEMENTS, METABOLISM AND ANATOMY ioa.factsanddetails.com

KANGAROOS AND PEOPLE: AUSTRALIANS, HISTORY, ART, SKIPPY ioa.factsanddetails.com

KANGAROOS IN MODERN AUSTRALIA: MEAT, LEATHER, CAR COLLISIONS AND ROO BARS ioa.factsanddetails.com

KANGAROO ISSUES: OVERPOPULATION, PESTS, CULLS, SHOOTERS, ANIMAL RIGHTS ioa.factsanddetails.com

KANGAROO ATTACKS: HUMANS, DOGS, HOW, WHY, WHERE ioa.factsanddetails.com

WALLAROOS: SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

WALLABIES: TYPES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

FOREST WALLABIES (DORCOPSIS): SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

PADEMELONS: SPECIES CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

TREE-KANGAROOS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

TREE-KANGAROOS IN AUSTRALIA: BENNETT'S, LUMHOLTZ'S, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

TREE-KANGAROOS IN PAPUA NEW GUINEA: SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

TREE-KANGAROOS IN WEST PAPUA, INDONESIA: SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

Kangaroos, Wallabies and Wallaroos

The terms "kangaroo", "wallaby" and "wallaroo" refer to different groupings, mainly based on size, within the family Macropodidae, with largest species being "kangaroos", the smallest being "wallabies", and "wallaroos" being in the middle. There are also the tree-kangaroos, another type of macropod which inhabit the upper branches of trees in the tropical rainforests of New Guinea, far northeastern Queensland, and some of the islands in the region. Small kangaroos include rock wallabies, hare wallabies and rat kangaroos.

Kangaroos are the largest macropods. A large male can be 2 metres (6 feet 7 inches) tall and weigh 90 kilograms (200 pounds). There are four species: red kangaroos, eastern grey kangaroos, western grey kangaroos, and antilopine kangaroos. Somes wallaroos are referred to as kangaroos.

Wallaroos are typically distinct species from kangaroos and wallabies. An exception is the antilopine wallaroo, which is commonly known as an antilopine kangaroo. There are two other species: common wallaroos and black wallaroos. Black wallaroos are the smaller of the two species. They have a head and body length of 60 to 70 centimeters (24 to 27.5 inches) and weigh 19 to 22 kilograms (42 to 49 pounds) for males and 13 kilograms (29 pounds) for females;

Wallabies have a head and body length of 45 to 105 centimeters (18 to 41 inches); and tail length of 33 to 75 centimeters (13 to 30 inches); the dwarf wallaby is the smallest of all known macropod species. It is 46 centimeters (18 inches) long and weighs 1.6 kilograms (3.5 pounds). There are about 30 wallaby species in Australia. There are seven species of dorcopsises and forest wallabies native to New Guinea,

Tree-Kangaroos range in size from Lumholtz's tree-kangaroo — with a body and head length of 48 to 65 centimeters (19 to 25.5 inches) tail of 60 to 74 centimeters (23.6 to 29 inches) and a weigh 7.2 kilograms (16 pounds) for males and 5.9 kilograms (13 pounds) for females — to the grizzled tree-kangaroo: with a length of 75 to 90 centimeters (29.5–35.5 inches) and weight of 8 to 15 kilograms (18–33 pounds); There are 14 tree kangaroo species in New Guinea and two in Australia.

Protemnodons — Extinct Giant Kangaroos

Protemnodon was a giant, now-extinct kangaroo that lived in Australia, Tasmania, and New Guinea in the Pliocene and Pleistocene Period (5.4 million to 11,700 years ago). Recent analysis of mtDNA extracted from fossils indicates that Protemnodon was closely related to Macropus (the kangaroo genus). A 2024 review of the genus recognized seven species: 1) P. anak (1874 the type species); 2) P. otibandus (1967); 3) P. snewini (1978); 4) P. tumbuna (1983); 5) P. mamkurra (2024); 6) P. viator (2024); 7) P. dawsonae (2024) Several species of Protemnodon survived up until around 50,000 years ago. P. tumbuna may have survived in the highlands of Papua New Guinea as recently as 12,000 years ago [Source: Wikipedia]

Based on fossil evidence, Protemnodon is thought to have been physically similar to wallabies, but generally larger and more robust. Protemnodon roechus was the largest in the genus, weighing around 170 kilograms (375 pounds). There have been reports in the popular media of towering ones that weighed 300 kilograms and were up 2.5 meters, ven three neters. One source said they were so big that scientists were studying whether they could hop.

Some studies show that Protemnodon species ranged from efficient hoppers of dry open habitats (such as P. viator) to slower, more quadrupedal forest dwellers (like P. tumbuna), while others have found that even species such as P. viator were very inefficient hoppers and primarily quadrupedal. The shape and articulation of the forelimbs suggests that they may have been adept at digging, while the claws on their hind feet had a curved shape, perhaps to help stabilise the animal on uneven ground.

Protemnodons went extinct but other kangaroos lived on. Kangaroos are survivors. Hopping — an efficient way to move at speed for long stretches — helped them flee their foes better than four-legged megafauna that are now extinct. [Source: Jeremy Berlin, National Geographic, February 2019]

See Separate Articles: WOMBATS, KANGAROOS AND THUNDER BIRDS ioa.factsanddetails.com ; ICE-AGE ANIMALS IN AUSTRALIA: WHEN, WHERE AND HOW THEY LIVED AND WENT EXTINCT ioa.factsanddetails.com

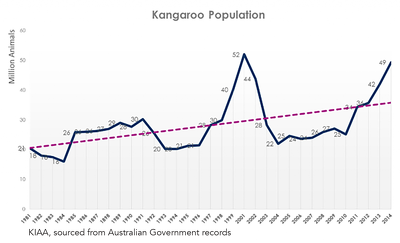

Kangaroo Population

The Australian government estimated that there were 42.8 million kangaroos in Australia in 2019, down from 53.2 million in 2013, when there about twice as many as kangaroos as people. In the 2000s it was estimated there were around 20 million wallabies. The numbers change quite a bit due to drought and rain conditions. According to the Australian ambassador to Japan, speaking at an event encouraging the Japanese to eat them, there were 25 million kangaroos in Australia in 2008, At that time there were 21.5 million people. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun; [Source: Terry Domico, Smithsonian Magazine [^^]

In the 1990s, hundreds of thousands of kangaroos contacted a virus that made them go blind. More than 200,000 of the five million kangaroos in New South Wales were infected. Among some mobs of western grey kangaroos a 30 percent of the animals carried the virus. The virus was carried by a sand fly, Some of the kangaroos died from starvation of dehydration, other injured themselves by leaping into tree or fences. Others were hit by vehicles or attacked by dogs or dingoes. Still others were able to adapt to their condition and survive.

There is currently an overpopulation of kangaroos. According to National Geographic in 2019 there was an an estimated 15.8 million red kangaroos, an equal number of eastern gray kangaroos, 4.3 million common wallaroos and an equal number of western gray kangaroos. It is possible to hunt these four species in designated harvest areas. Advocates of commercial culling say it keeps roo numbers in check. Critics say hunting quotas are based on inflated population estimates. [Source: National Geographic, February 2019]

Kangaroo Population Booms and Busts

Kangaroo populations go through booms and busts mainly with the former occurring when rainfall in plentiful and the latter when there are droughts but can also occur when booming populations eat up all the food. Li Cohen of CBS News wrote: An excessive population poses a risk to the animals themselves, as a surplus of animals means that there is not enough food and many end up starving to death. This is what happened in 2016 and 2017, when government figures showed that there were nearly 45 million kangaroos — about double the amount of people in the country, according to the BBC.

That population boom was believed to be because of a bout of rainy conditions increasing vegetation, but like many rainy seasons, it ended with a drought — and a heavy price. "The last drought we estimated that 80 or 90 percent of the kangaroos in some areas died," ecologist Katherine Moseby told AFP. "They are starving to death — going into public toilets and eating toilet paper, or lying on the road starving while their joeys are trying to feed."

Dennis King, executive officer for the Kangaroo Industry Association of Australia, told AFP that he believes the country could see another situation like that soon, as weather in recent years has created conditions for another boom. "After three years of La Nina right down the east coast, we've seen the perfect growth scenario for kangaroos over the next couple of years," he said. "The breeding cycle really speeds up." And if that happens, he believes the population could hit as many as 60 million kangaroos — more than 2.3 times the number of people in Australia.

The droughts of 1982 and 1983 took a heavy toll on the kangaroo population. A year after the drought was over, however, their numbers increased by 40 percent. This miraculous comeback was due to fact that females, who had stopped breeding during the drought, were able to conceive seven days after the first rain.

During a severe drought in 2003, the Washington Post reported: Starving kangaroos have been terrifying drought-stricken Australian communities for months, gathering in school yards, invading towns and risking bullets from angry farmers by raiding gardens. While the drought on the eastern seaboard ends in floods, mobs of kangaroos are still bounding down main streets of parched country towns in search of food. In one reported case, kangaroos attacked and killed a dog. The worst drought in 100 years is cutting through a kangaroo population farmers say had grown to three times the nation's 20 million people, and turned the cuddly-looking animal into an overgrown pest. "All around the paddocks, under every tree, there's dead 'roos. What a terrible way to go, starving to death in their millions," kangaroo expert Brian Rutledge said from his property in the Queensland outback. [Source: Washington Post, June 1, 2003]

Kangaroo and Macopod Characteristics

The largest kangaroo is the red kangaroo. It stands 1.8 meters (five feet 11 inches) tall, has a length of 2.85 meters (nine feet four inches), including the tail, and weighs up to 90 kilograms (198 pounds). The tallest marsupial on record is a 2.13-meter (7-foot)-tall 79-kilogram (175-pound) red kangaroo. In the wild kangaroos seldom live be older than seven years of age but some live to the ago of 30. Their most dangerous natural enemy is drought.

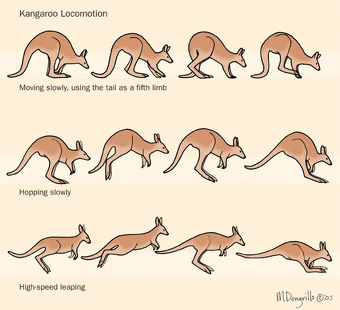

Kangaroos have their short, dexterous forearms with sharp, pointed nails. They use these forearms and paws like arms and hands to scratch and groom themselves and hold things, They are drawn up again the body in a kind of begging position when they hop. Kangaroo are incredibly bottom-heavy because of the great mass behind their tails and legs. The tail of a red kangaroo is near 1.3 meters (four feet) long, almost half its length, and filled with strong muscles and is nearly as thick as it body at its base. Their tails serve as a counterbalance when hopping, a kind of chair when standing still and a fifth limb when moving slowly.

A kangaroo heart is large and powerful — 1.5 times larger than similarly-sized mammals. A colony of strongyle worms in a kangaroo's stomach indicates a healthy animal. With large eyes located on either side of their head, kangaroos have a wide field vision. They are particularly adept at detecting motion. "A kangaroo's hearing," says Terry Domico, author a book about kangaroos, "may be its most important sense...The two large ears can be rotated independently; often one will point forward while the other faces the rear...Even when lying down, its ears are in constant motion."

Kangaroo skin is unique. The collagen fibers that make up kangaroo hide are fine, concentrated, highly uniform, and parallel to the surface of the skin, unlike cow skin’s irregular, bundled structure. Kangaroo hide also has very low fat content and a thin grain layer, without sweat glands and erector pili muscles. [Source: Stridewise]

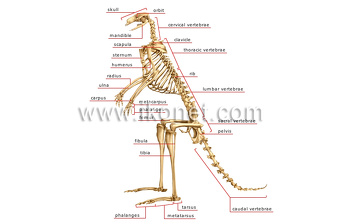

Kangaroo Skull and Teeth

Phil Myers wrote in Animal Diversity Web : Macropods have a long and narrow skull, usually a long rostrum (hard, beak-like structures projecting out from the head or mouth), and a head that seems small relative to the size of the body. The masseteric fossa (shallow, depressed area on a bone) on the lower jaw is deep, and a masseteric canal is present. Masseter muscles are particularly powerful in herbivores to facilitate chewing of plant matter. [Source: Phil Myers, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

The macropod dental formula is 3/1, 1-0/0, 2/2, 4/4 = 32-34 (one species has additional, supernumerary molars). Macropods have enlarged first lower incisors ( diprotodont). Their second and third upper incisors lie lateral to the first (vs. behind first in other diprotodonts). This arrangement results in a continuous cutting edge at the front of the mouth. When the animals bite, the procumbent lower incisors do not meet the upper teeth; rather, they press into a tough pad on the roof of the mouth, located just posterior to the upper incisors.

This arrangement is very much like that seen in bovid and cervid artiodactyls. The canines are absent or vestigial, and a substantial diastema separates incisors and cheek teeth. The pattern of tooth replacement is unusual. A young kangaroo has two blade-like upper premolars, which are soon shed and replaced by a third premolar (which is also blade-like). The molars erupt in succession, with the first falling out and others moving forward as the animal grows. The molars of macropods are hypsodont, quadritubercular, and either selenodont or lophodont or a combination of the two forms. |=|

Kangaroo Hopping

Hopping is the primary mode of locomotion for large marsupials such as kangaroos, wallabies, and rat-kangaroos. They are the only large animals known to hop.Kangaroos can cruise at speeds of 28 to 32 kilometers per hour (15 to 20 miles per hour) and can accelerate to twice that speed if necessary. Eastern grey kangaroos and red kangaroos have been clocked hopping at 64 kilometers per hour (40 miles per hour). A female red kangaroo once jumped 12.8 meters (42 feet). According to the Guinness Book of Records, there is an unconfirmed report of a eastern gray kangaroos leaping 13.6 meters (44½ feet). A gray kangaroos was observed jumping over a three-meter-high (ten-foot-high) pile of timber.

Many kangaroo species use less energy hopping at 28 to 32 kilometers per hour (15 to 20 miles per hour) mph than they do walking more slowly, when their heavy tails act like loads that have to be carried. When they hop the tail acts as a counterweight rather than a burden and they can move along at steady clip for miles, using less energy than other animals do when they run.

The hindquarters and legs make up to three quarters of a kangaroo's weight. There are four toes on each of the two find feet, with the one toe considerably larger than the others. Hopping kangaroos push off on their enlarged fourth toe, and to a lesser degree their fifth toe. The first toe has all but disappeared and their second and third toe are fussed together into a claw used primarily for grooming and scratching. The up and down motion of the tail of a hopping kangaroo acts as a counter-balance and the hopping motion itself helps pump air in and out of the kangaroos lungs.

Kangaroos are able to move so quickly by storing energy with each hop utilizing the principal of the spring. "Because of the elastic storage of energy in its tendons," says Domico, "the faster a 'roo' travels the more energy it saves...Kangaroos increase their speed by increasing their stride."

See Separate Article: KANGAROOS HOPPING: MOVEMENTS, METABOLISM AND ANATOMY factsanddetails.com

Most Kangaroos are 'Left-Handed'

Wild kangaroos use their left hands more when performing everyday tasks such as grooming and feeding, a study published in June 2015 in the journal Current Biology, suggests. The research, conducted by Russian scientists from St Petersburg State University, is the first demonstration of population-level "handedness" in a species other than humans. The researchers traveled to Australia to do the fieldwork, collaborated with Janeane Ingram, a wildlife ecologist and PhD student at the University of Tasmania and and spent hours observing multiple species in the wild in Tasmania and New South Wales. [Source: BBC, June 18, 2015]

The BBC reported: Two species of roo and one wallaby all showed the left-handed trend; some other marsupials, which walk on all fours, did not show the same bias. Ms Ingram told the BBC the work had faced some scepticism. "Unfortunately, even my own colleagues think that studying left-handed macropods, external is not a serious issue, but any study that proves true handedness in another bipedal species contributes to the study of brain symmetry and mammalian evolution," she said.

Senior author Dr Yegor Malashichev said there had been a "widespread notion" that handedness was a uniquely human phenomenon, until research in the last 10-20 years showed that asymmetry in behaviour and brain structure was surprisingly widespread. But examples of left- or right-handedness tended to be specific to particular behaviours, and were not consistent across a population. "As one of our reviewers pointed out, laterality is also obvious in how parrots hold their food or how your dog shakes hands," Ms Ingram said. "But these examples of lateralisation have not been proven at the population level."

The new study found a consistent left-handed bias across eastern grey kangaroos, red kangaroos, and red-necked wallabies — no matter whether the animals were grooming, feeding, or propping themselves up. Dr Malashichev He and his colleagues suggest that their discovery is an example of "parallel evolution". This is because handedness seems to have appeared in primates, which belong in the group of placental mammals, as well as the marsupials in the new study, but not in related animals across these two branches of the evolutionary tree. The researchers also argue that posture is an important factor. The left-handed trend was only seen in species that stand upright on their hind legs, using their forelimbs more regularly for tasks other than walking. Similarly, they suggest, the transition to an upright posture may have been key to primates developing handedness.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org , National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, David Attenborough books, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2025