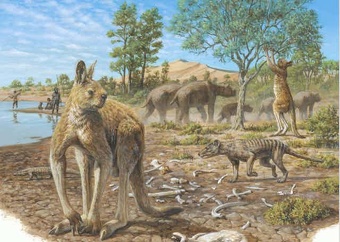

ICE-AGE ANIMALS IN AUSTRALIA

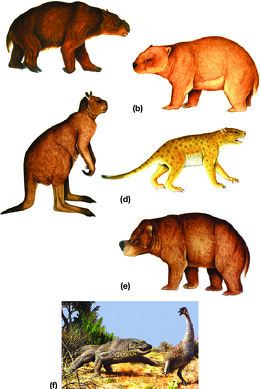

Australian megafaunal species that became extinct in the late Pleistocene: a) Diprotodon optatum; b) Phascolonus gigas; c) Procoptodon goliah; d) Thylacoleo carnifex; e) Zygomaturus trilobus; f) Megalania chasing Genyornis, from Researchgate

Among the marsupials that lived millions of years ago in Australia were a cow-size wombat, a wolf-size marsupial lion and an order of marsupials so unusual it was called a "Thingaodonta." There were also towering 300-kilogram super-kangaroos up to 2.5 meters tall called protemnodon that were so big that scientists are studying whether they could hop. Prehistoric animals found as recently as 50,000 years ago on the Australian continent included massive carnivorous ghost bats, platypus with large canine teeth, rabbit-size creatures with huge projecting incisors, and nine foot birds that weighed half a ton.

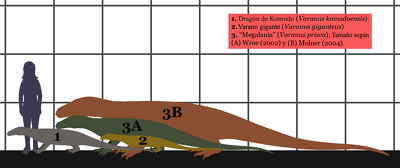

Some 90 giant animal species once inhabited Australia and Papua New Guinea. Animals that roamed the dense rain forests of Queensland millions of years ago included carnivorous kangaroos, six-foot-long lungfish, prehistoric emus, tree-dwelling crocodiles, giant land crocodiles, carnivorous kangaroos, and the the largest known lizards. Among the latter were 590-kilogram (1,300 pound), 6.5-meter (21-foot-long) giant goannas and six-meter long venomous lizards called megalania.

During the ice ages, when sea levels were 65 meters lower than they are now and the climate was wetter than it is today, Australia, Tasmania and New Guinea were part of a single continent called Meganesia. The geological and biological record bears this out. New Guinea, for example, also has kangaroos. A couple of Indonesian islands may have been part of the 60,000 year old continent: a previously unidentified species of tree kangaroo was discovered on an island near Irian Jaya in 1994. [Source: Tim Flannery, Natural History, June 1993, December 1995]

Between 11 and 16 million years ago, during the Miocene era, Australia's rainforests were drying up and turning into the deserts that dominate its landscape today. Paleontologists have unearthed roughly 2,000 fossils of insects, fish, spiders, and plants from this era at the McGraths Flat site southeastern Australia. The fossils include fish with their last meals still in their stomachs, insects dusted with grains of pollen from the last plant they visited, and bugs' eyes and muscles preserved in exquisite detail. [Source: Morgan McFall-Johnsen, Business Insider, January 8, 2022]

See Separate Articles: GIANT ICE-AGE ANIMALS IN AUSTRALIA: WOMBATS, KANGAROOS AND THUNDER BIRDS ioa.factsanddetails.com ; DINOSAURS IN AUSTRALIA: TYPES, CHARACTERISTICS, WHEN AND WHERE ioa.factsanddetails.com

Large Ice Age Animals in Australia

Ancient large animals in Australia included the rhino-size diprotodon, a wombat-like marsupial plant eater that somewhat resembled a buffalo; giant kangaroo rats, weighing 90 pounds; a Volkswagen-size tortoise; eight-meter-long snakes that were one meter in diameter; and the Genyornis, an ostrich-size flightless bird.

The diprdtodon was a plant eating marsupial the size of a rhinoceros. It t had a hoof-like things on its nose. The diprdtodon and a third of the mammals that lived in Australia around the time men first arrived went extinct. The most likely explanation is that they were hunted to extinction by the first inhabitants of Australia.

A 1,500-pound giant bird that lived in Australia eight million years is regarded as the largest bird ever. It was slightly larger than the elephant bird of Madagascar. Fossils of the giant were found 100 miles northeast of Alice Springs. The Genyornsi was a 400-pound flightless bird. It became extinct about 50,000 years ago. Scientists think humans caused it extinction because the first humans arrived about 60,000 years ago and vegetation was plentiful at the time of their extinction.

Ice Age Carnivores in Australia

Large prehistoric carnivores that lived iin Australia included Megalania, giant carnivorous goannas that perhaps weighed as much as a ton and reached lengths of 21 feet; Quinkana, 10-foot-long, 500 pound land crocodiles that seemed to able to survive without water, and may have jumped from trees onto their prey.

The womambi was large python-like snake that weighed over 100 pounds and had a 12-inch girth. It had an enormous head filled with hundreds of tiny teeth. It lived in a number of different environments including rocks and oases and was found much further south than large snakes today. Marsupial lions as large as their African counterparts may have dragged captured kangaroos into a tree just as leopards do with their prey today.

But one thing that has always mystified scientists about Australia and New Guinea is overall lack of large carnivorous mammals. The other continents have lions, tigers and bears, yet the largest indigenous meateater on Meganesia (Australia and New Guinea) today are the poodle-size Tasmanian devil and the weasel-like spotted-tail quoll.

The most likely explanation as to why giant carnivorous creatures thrived hundreds of thousands of years ago but are gone today is the climatic factors such as drought reduced their habitat and weakened the gene pool of the species. When Aboriginal first arrived 40,000 years they finished them off the same way the first Americans likely wiped out the wooly mammoth and giant ground sloths.

1.6-Million-Year-Old Giant Kangaroos and Marsupial Lions

In 2002, scientists announced that they had discovered by accident skeletal remains of giant kangaroos, wombats and marsupial lions, perhaps as old as 1.6 million years old, in deep sinkholes in the remote Nullarbor Plain in Western Australia state overlooking the Great Australian Bight. The most impressive find was a near perfect skeleton of a flesh-eating marsupial lion, called Thylacoleo Carnifex, or Leo, thought to have died out 46 000 years ago. "This is the most amazing collection of mass skeletons that I have ever seen," said expedition leader John Long, curator of vertebrates for the Western Australian Museum. "It's like a crime scene," he said. [Source: James Regan, Reuters, July 31, 2002]

Reuters reported: Radiation levels in the caves were measured to help date the bones accurately, and samples have been sent to England's Oxford university for DNA testing, Long said. The bones of seven other types of extinct animals, including a pony-sized wombat and possibly the largest remains of a kangaroo, more than three meters (16 feet) high, were also found.

The Nullarbor contains numerous sinkholes and caves, some rich in fossils. Over time the sinkholes became death traps for animals that fell in and died. The dry dark conditions of such tombs ensured that remains were well preserved, enabling scientists to extract DNA samples from traces of soft tissue, hair and blowfly remains, for dating and forensic testing, Long said. Long said the cache might have gone undetected but for a group of cavers who first abseiled into the holes in search of uncharted adventure last May. "Thankfully, they left everything intact and were aware of the fragility of the bones and the possibility of contamination," Long said.

Some of the striking "Leo" features have led scientists to conclude the species was a voracious pouched carnivore, far removed from any of the cuddly looking creatures which now inhabit Australia. It would have been equipped with a spectacular pair of piercing lower incisors and huge teeth used to tear into the flesh of unfortunate prey. Curiously, the limbs are adapted for climbing and grasping rather than for running. "The paws are well armed with retractable claws and the hands have large opposable thumbs," Long said.

Presumably it ate ground-dwelling plant eaters, such as the giant leaf-eating kangaroo. Like modern lions and leopards, Leo would have clamped the prey's neck and windpipe in its jaws, killing by suffocation. The skeleton of this marsupial pouched lion is on display in a hastily at the museum in Perth.

How Did Large Ice Age Animals in Australia Die Out: Humans or Climate?

There is a debate on how large ancient animals became extinct: by human intervention or perhaps climatic change. Some of these creatures were probably wiped out by early Aboriginals just as giant sloths and wooly mammoths were probably exterminated by early American Indians. The oldest known grinding stones for plants appeared around 30,000 years ago. The might have been created because the easy animals to hunt for meat were extinct.

Some prehistoric Australian animals (and the approximate time they went extinct): 1) Polrchestes, carnivorous kangaroos (30,000 years ago); 2) genyornis (25,000 years ago); 3) diprotodon (20,000 years ago); 4) megalonia prisca and giant goanna (12,000 years ago); 5) Procoptadon, the giant kangaroo (10,000 years ago); 6) thylacoleo, marsupial lion, (9,000 years ago); 7) giant echidna (9,000 years ago).

Some may have been hunted to extinction. A more likely explanation is they were wiped by huge man-made brush fires that changed the ecology of their habitats. According to a report in Science, "All marsupials exceeding 100 kilograms, or 19 species, and 22 of 38 species between 10 and 100 kilograms became extinct, along with three large reptiles and the ostrich-size Genyornis...We suspect the systematic burning by the earliest colonizers — used to secure food, promote new vegetation growth, to signal other groups of people and for other purposes — differed from the natural fire cycle, that key ecosystems were pushed past a threshold from which they could not recover." Scientists also don’t think the animals were overhunted because there is little evidence that early people ate the large animals.

A study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in 2013, suggested that climate change killed most of Australia’s giant animals as they were mostly extinct by the time humans arrived about 45,000 to 50,000 years ago and there is a lack of evidence of hunting of these beasts by humans. The study led by the University of New South Wales, found that while human involvement in the disappearance of the megafauna was possible, climate change was the more likely culprit. “There is no firm evidence whatsoever that a single human ever killed a single individual megafauna,” the study’s lead author, University of New South Wales zoologist Stephen Wroe told AFP. “Not a thing. There is not a single kill site in Australia or (Papua) New Guinea. There’s not even the sort of tool kit that you would typically associate for hunter gatherers with killing big animals.” [Source: AFP, May 8, 2013]

Wroe said the fossil records showed that the clear majority of now extinct species of megafauna “can’t be placed within even 50,000 years of when humans were thought to have first arrived.” “No more than about 14, perhaps as few as eight, species were clearly here when humans made foot-fall,” he said. Wroe said there was also mounting evidence that their extinction took place over tens, if not hundreds, of millennia during which time there was a progressive deterioration in the climate. “There is clear evidence that the climate was changing over a long period of time and becoming progressively more extreme,” he said, adding this could have been harsh enough to kill off the giant animals, many of which were herbivores.

Study Suggests Large Ice Age Animals in Australia Died Out Because of Humans

But there are still those that argue humans killed off Australia's giant beasts. In a study published in in Science in March 2012, scientists have linked a dramatic decrease in spores found in herbivore dung to the arrival of humans in Australia 41,000 years ago and argued this was evidence that humans hunted Australia's giant vertebrates. [Source: BBC, March 24, 2012]

The BBC reported: scientists studied dung samples from 130,000 and 41,000 years ago, when humans arrived, and concluded hunting and fire were the cause. The extinction in turn caused major ecological changes to the landscape.The scientists looked at pollen and charcoal from Lynch's Crater, a sediment-filled volcanic crater in Queensland that was surrounded by tropical rainforest until European settlement. They found Sporormiella spores, which grow in herbivore dung, virtually disappeared around 41,000 years ago, a time when no known climate transformation was taking place.At the same time, the incidence of fire increased, as shown by a steep rise in charcoal fragments. It appears that humans, who arrived in Australia around this time,hunted the megafauna to extinction, the scientists said.

Susan Rule of the Australian National University in Canberra and her colleagues concluded that vegetation also changed with the arrival of humans. Mixed rainforest was replaced by leathery-leaved, scrubby vegetation called sclerophyll. But these changes to the landscape took place after the animal extinctions, indicating that they were the result of the extinction and not its cause, they said.

Human-lit fire — deliberately targeted and more frequent than lightning — had a devastating effect of plants that had previously been protected. "Any climate change at those times was modest and highly unlikely to affect the outcome," author Matt McGlone wrote in Science. Lead research author Chris Johnson, from the School of Zoology at the University of Tasmania, said the research raised further questions about the ecological impact of the extinction. "Big animals have big impacts on plants. It follows that removing big animals should produce significant changes in vegetation." The removal of large herbivores altered the structure and composition of vegetation, making it more dense and uniform, he said. "Getting a better understanding of how environments across Australia changed as a result of megafaunal extinction is a big and interesting challenge, and will help us to understand the dynamics of contemporary Australian ecosystems."

Dr John Alroy, from the Department of Biological Sciences, Faculty of Science at Macquarie University, New South Wales, said the debate about whether humans contributed to widespread extinction should "be over now". "But it has dragged on for nearly a half-century now because the idea that stone age hunters could cause such utter havoc across three entire continents over very short time spans strikes many people as incredible. "Like it or not, though, it's the truth, and it's time for us to all confront it."

However, Gavin Prideaux, a lecturer in vertebrate palaeontology in the School of Biological Sciences at Flinders University, South Australia, said further research was necessary. He said the latest study "supports a mounting number of studies that have argued that climate change was not primarily responsible for the Late Pleistocene extinctions in other parts of the continent. "To test the inferences from this paper we might look at similar lake records from other regions of Australia and seek fossil deposits in the northeast that preserve bones of the giant animals themselves."

Riversleigh and Naracoorte Fossil Mammal Sites — UNESCO World Heritage Site

The Australian Fossil Mammal Sites in Riversleigh and Naracoorte were inscribed as UNESCO World Heritage Sites in 1994. According to UNESCO:Australia is regarded as the most biologically distinctive continent in the world, an outcome of its almost total isolation for 35 million years following separation from Antarctica. Only two of its seven orders of singularly distinctive marsupial mammals have ever been recorded elsewhere. Riversleigh and Naracoorte, situated in the north and south respectively of eastern Australia, are among the world’s 10 greatest fossil sites. They provide a superb fossil record of the evolution of this exceptional mammal fauna. This serial property provides outstanding, and in many cases unique, examples of mammal assemblages during the last 30 million years. [Source: UNESCO]

The older fossils occur at Riversleigh, in northwest Queensland, which boasts an outstanding collection from the Oligocene to Miocene, some 10-30 million years ago. The more recent story then moves to Naracoorte, where one of the richest deposits of vertebrate fossils from the glacial periods of the mid-Pleistocene to the current day (from 530,000 years ago to the present) is conserved. This globally significant fossil record provides a picture of the key stages of evolution of Australia’s mammals, illustrating their response to climate change and to human impacts.

These fossil deposits are outstanding examples representing major stages of earth's history, including the record of life. Riversleigh provides exceptional, and in many cases unique, mammal assemblages from 10-30 million years ago. These assemblages document changes in habitat from humid, lowland rainforest to dry eucalypt forests and woodlands, and provide the first fossil record for many distinctive groups of living mammals such as the marsupial moles and feather-tailed possums. The assemblages recovered from the caves at Naracoorte Victoria Fossil Cave preserve an outstanding record of more recent terrestrial vertebrate life.

At Riversleigh the mammal fossil assemblages indicate the rainforest origins for the majority of mammal groups that today occupy arid Australia. The vertebrate species present at Naracoorte provide a key clue to understanding their responses to climate change, and include superbly preserved examples of the Australian ice age megafauna (giant, now extinct mammals, birds and reptiles), such as the enigmatic extinct marsupial lion (Thylocoleo carnifex). This site also hosts essentially modern species including marsupials such as the Tasmanian devil (Sarcophilus harrisii), Tasmanian tiger (Thylacinus cynocephalus), wallabies and possums; placental mammals including mice and bats; and snakes, lizards, frogs and turtles. The Naracoorte assemblages span the probable time of arrival of humans to Australia and thus are of additional value in helping unravel the complex relationships between humans and their environment. They highlight the impacts of both climatic change and humans on Australia’s mammals, including its now vanished megafauna.

In July 2010, in an article published in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, scientists said they had discovered a cave at Riversleigh filled with 15-million-year-old fossils of prehistoric marsupials. The “treasure trove of beautifully preserved fossils” included 26 skulls from an extinct, wombat-like marsupial called Nimbadon lavarackorum, an odd sheep-sized creature with giant claws. "It's extraordinarily exciting for us," said University of New South Wales paleontologist Mike Archer, co-author of the article. "It's given us a window into the past of Australia that we simply didn't even have a pigeonhole into before. It's an extra insight into some of the strangest animals you could possibly imagine."

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org , National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, David Attenborough books, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2025