Home | Category: Kangaroos, Wallabies and Their Relatives

WALLAROOS

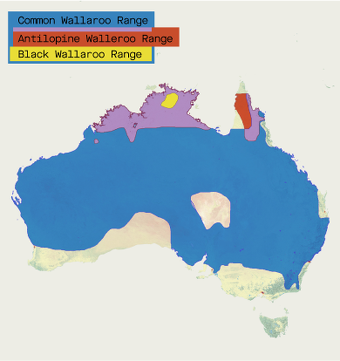

Wallaroo species: 50) Black Wallaroo (Osphranter bernardus), 51) Antilopine Wallaroo (Osphranter antilopinus), 52) Common Wallaroo (Osphranter robustus)

Wallaroo is the common name for several species of moderately large macropods. Theoretically wallaroos are marsupial larger than wallabies but smaller than kangaroos. In practice however some of them are larger than kangaroos: weighing as much as 50 kilograms (110 pounds) and reaching a height of 1.2 meters (four feet). The word "wallaroo" is from Dharug walaru, which means "rock kangaroo" in an aboriginal language with spelling influenced by the words "kangaroo" and "wallaby".

Wallaroos are typically distinct species from kangaroos and wallabies. An exception is the antilopine wallaroo, which is commonly known as an antilopine kangaroo when large, an antilopine wallaby when small, or an antilopine wallaroo when of intermediate size.

There are three species of wallaroo: Common wallaroos (Osphranter robustus or Macropus robustus) are the best-known and widespread species of wallaroo. Black wallaroos (Osphranter bernardus or Macropus bernardus) occupy an area of steep, rocky ground in Arnhem Land in northern Australia. Antilopine wallaroos (Osphranter antilopinus or bernardus Macropus) are known as antilopine kangaroos and antilopine wallabies, They live grassy plains and woodlands and are gregarious, unlike other wallaroos which are solitary.

Wallaroo used be categorized in the genus macropus but are now listed in the genus Osphranter. Osphranter is a genus of large marsupials in the family Macropodidae, commonly known as kangaroos and wallaroos (among other species). In 2019, a reassessment of macropod taxonomy determined that Osphranter and Notamacropus, formerly considered subgenera of Macropus, should be moved to the genus level. This change was accepted by the Australian Faunal Directory in 2020.The genus has a fossil record that extends back at least into the Pliocene Period (5.4 million to 2.4 million years ago). [Source: Wikipedia]

RELATED ARTICLES:

WALLABIES: TYPES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

KANGAROOS AND WALLABIES (MACROPODS): CHARACTERISTICS, HISTORY, POPULATIONS ioa.factsanddetails.com

WALLABY SPECIES ioa.factsanddetails.com

WALLABY SPECIES OF SOUTHWEST AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

KANGAROO BEHAVIOR: FEEDING, REPRODUCTION, JOEYS ioa.factsanddetails.com

KANGAROOS HOPPING: MOVEMENTS, METABOLISM AND ANATOMY ioa.factsanddetails.com

MARSUPIALS: HISTORY, EVOLUTION, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

MARSUPIALS IN AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

MARSUPIALS IN AUSTRALASIA (AUSTRALIA, NEW GUINEA, NEARBY ISLANDS) ioa.factsanddetails.com

Common Wallaroos

Common wallaroos (Osphranter robustus or Macropus robustus) are also known as hill wallaroos or simply wallaroos. There are an estimated 4.3 million of them and they range across almost all of Australia. Adult males weigh 22 to 60 kilograms (44 to 132 pounds). The longest known lifespan of a common wallaroo in the wild is 24 years and the longest known lifespan in captivity is 22 years. What limits lifespan is the degradation of the immune system and organ function through aging. Their lifespan in captivity is typically 18 to 22 years. [Source: Kyle Davis, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

There are four subspecies of common wallaroo: 1) eastern wallaroos (O. r. robustus) and 2) euro wallaroos (O. r. erubescens), which are both widespread, and 3) Barrow Island wallaroos (O. r. isabellinus) and Kimberley wallaroos (O. r. woodwardi), which have more restricted ranges. Common wallaroos are the most widespread macropod in Australia. Eastern wallaroos are one of the more common macropods. They are often seen in New South Wales and Queensland.

Common wallaroos are often found on or in rocky hills, caves, and rock formations with large overhangs — anything that provides shade and shelter from the intense heat during the day. They are also commonly found in shrublands and along streams, near their main food and water sources. A study by Taylor (1983) found that, when Common wallaroos seek shelter, larger adult males occupied much rockier areas than smaller males or females. They live at elevations from sea level to 500 meters (1640 feet). Average elevation is 330 meters (1082.68 feet). |=|

Common wallaroos are not endangered. They are designated as a species of least concern on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List due to their wide distribution in Australia and the fact that significant populations occur in protected areas. They have no special status on the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). The Burrow Island subspecies of common wallaroos is threatened by poor health as a result of poor nutrition. This subspecies consists of about 18,000 individuals.

Common wallaroos have historically been hunted for meat, leather and fur, which is now largely illegal due to the Environmental Protection and Biological Conservation Act of 1999. However, they are sometimes taken in culls along with larger kangaroos and their meat and leather is utilized by the kangaroo industry.

Common Wallaroo Characteristics and Diet

Common wallaroos are hopping, bipedal marsupials with a light gray to black coat. They range in weight from 18 to 42 kilograms (39.6 to 92.5 pounds) and range in length from one to 1.4 meters (3.3 to 4.6 feet). Their average basal metabolic rate is 33.056 watts. Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present: Males are larger than females. [Source: Kyle Davis, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Compared to other wallaroos, common wallaroos have shorter and wider torsos and shorter limbs, both presumed adaptations for their rocky terrain they often inhabit. They also have short but wide hind feet with powerful legs used to jump up to four meters. The feet have roughened soles on the bottom for extra grip.

Common wallaroos are herbivores (eat plants or plants parts). They mostly graze (eat low-growing plants as opposed to browse on plant parts higher up) on soft-textured grasses and shrubs. Foraging mainly occurs within their home range. In the Pilbara district in northwest Australia, which is very dry, they do fairly well as a esult of the large number of sheep pastures. Their ability to conserve water helps them live in the harsh conditions of the Australia Outback. They can live up to two weeks without drinking water; instead metabolizing water from the plants they eat. Common wallaroos may help to disperse seeds through their grazing.

Common Wallaroo Behavior

Common wallaroos are terricolous (live on the ground), saltatorial (adapted for leaping), diurnal (active mainly during the daytime), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), sedentary (remain in the same area), social (associates with others of its species; forms social groups). Eastern wallaroos are mostly nocturnal and solitary. Common wallaroos home territories range from 40 to 76 square kilometers (15.4 to 29.3 square miles), with average being 65 square kilometers (25 square miles). The home range depends on suitable vegetation availability. Most Common wallaroos find a large patch of vegetation and stay there but have been known to travel up to 18 kilometers outside of their home range in search of food. [Source: Kyle Davis, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Common wallaroos move around by hopping on their massive hind legs like kangaroos. They generally move around to new feeding areas within their home range. They sense and communicate with vision, touch, sound and chemicals usually detected by smelling. The most frequent visual and tactile forms of communication are grooming and fighting. Common wallaroos interact with each other through grooming. Grooming occurs between every individual but is more frequent between young and their mothers. Males rarely groom each other.

Males sometimes engage in fighting, or "boxing" with other males. In such fights males mostly use their powerful legs to kick-box until one contestant forfeits. Most fights involve two sexually-mature males competing for females and displaying dominance. During the fight males bob their heads, arch their heads back and flick their neck into an erect posture. Males do this head-bobbing motion multiple times until it attracts another male's attention. Other males then either fight or display submission. The matches are rarely fatal or produce serious injuries. Males display dominance this this way in order to stay at the top of their social hierarchy or gain access to females for mating.

As an alarm call, common wallaroos, make a hissing noise by exhaling through their nose. Common wallaroos are preyed on by red foxes, introduced species to Australia, which mainly take young wallaroos when they are fresh out of the mother's pouch and defenseless. Common wallaroos avoid predators by forming groups and using alarm signals. Alarm signals are powerful and loud foot stomps, followed by high-pitched hisses that warn others of danger — to which they respond by running away.

Common Wallaroo Mating, Reproduction and Offspring

Common wallaroos are monogamous (have one mate at a time). They generally breed once a year and engage in year-round breeding. The number of offspring is one. The gestation period ranges from 30 to 38 days, with the average being 36 days. Breeding intervals are influenced by the number of pouch young a female. A female can't accommodate two joeys and must wait until one has left the pouch before another can be raised. Females wait until weaning has stopped in order to mate again. [Source: Kyle Davis, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

To attract a mate, male common wallaroos display their dominance to other males and show their strength to females through frequent "boxing matches" where two males fight until one surrenders (See Behavior Above). Males interact with a potential mate by sniffing her and displaying himself to her. This display includes a side-to-side sweeping motion, indicating to the female that he is ready to mate

Parental care is provided mostly by females but males are involved in protecting the group. During the pre-birth, pre-weaning and pre-independence stages provisioning is done by females and protecting is done by males and females. The post-independence period is characterized by the association of offspring with their parents. The weaning age ranges from 15 to 16 months. The average in which young become independent ranges from eight to nine months. Females reach sexual or reproductive maturity at 21 to 24 months; males do so at 18 to 19 months. [Source: Kyle Davis, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Common wallaroo young are altricial, meaning they are relatively underdeveloped at birth. Their average weight at birth is only 0.7 grams. The young, or joey, stays in the mother's pouch after birth for protection and remains there full-time until around age six months, when they may tumble out of the pouch, but quickly climbs back in. Soon after, the joey becomes active and grows rapidly. At eight to nine months mothers don't allow their joeys to climb back into their pouch and the joeys are considered independent. After independence, young continue to have a close relationship with their mother, including resting together and grooming each other. The father provides protection against predators for the entire weaning period. After about 20 months, the young are fully independent, no longer relying on a parent for any kind of food acquisition. At this age, their relationship with the father usually weakens but their relationship with their mother remains strong.

Black Wallaroos

Black wallaroos (Osphranter bernardus or Macropus bernardus) and the smallest wallaroo and the most heavily built wallaroos. Occupying an area of steep, rocky ground in Arnhem Land in northern Australia, they have a head and body length of around 60 to 70 centimeters (2 to 2.3 feet), excluding their tail. Males weigh 19 to 22 kilograms (42 to 49 pounds) females about 13 kilograms (29 pounds). Because they are very shy and wary of humans and found only in a small area of remote and very rugged country, relatively little is known about them. Their average lifespan in captivity is 11.8 years.

Black Wallaroos are found in limited areas on the sandstone escarpment and plateau of the western edge of Arnhem Land, a region of northern Australia located to the west of the Gulf of Carpentaria. They usually occur in a wide range of vegetation types varying from closed forests to open Eucalyptus forests to hummock grasslands and heaths. In most cases, they are found in areas that have large boulders in the landscape. |=|

Black wallaroos are one of the smallest species in the kangaroo family. They are roughly two thirds the size of common wallaroos. Females are about 80 centimeters (2.6 feet) tall and males about one meter (3.3 feet) tall. Their common name comes from the color of the male fur, which ranges from sooty brown to glossy black. Females are a dark brown to grey in color. The ears are shorter than common wallaroos. Unlike kangaroos where the muzzle is covered with hair, the black wallaroo's nose is completely naked. |=|

On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List black wallaroos are listed as Near Threatened. In CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild) they have no special status. They do not interact much with humans mainly because they live in such a small, remoate area of Australia. They do not intrude on grazing land, and do not disturb crops. They are considered not good to eat — the meat has a rank and unpleasant smell and taste. A large part of the habitat of black wallaroos is located in Kakadu National Park in Australia, which is protected. The largest threat to their survival are fires and droughts, perhaps exacerbated by climate change.

Black Wallaroo Behavior and Reproduction

Black Wallaroo are motile (move around as opposed to being stationary and somwhat social (associates with others of its species; forms social groups). They sense using touch and chemicals usually detected with smell. They tend to be solitary except while breeding; with no more than three individuals being found in a group (usually an adult male and female, along with a large joey. Mothers often groom their young while it is still suckling but after it has exited the pouch. Aggressive behaviors have been observed between males, but rarely lead to injury, and usually end quickly. Threatening displays include stiff-legged walking, pulling on grass or bushes, and upright postures. Black Wallaroo animals are extremely shy, running until out of sight if approached. This makes them difficult to observe, and makes them one of least studied kangaroo and wallaby. [Source: Evan Hyatt, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Black Wallaroos are grazers (primarily eat grass or other low-growing plants), who spend between seven and 14 hours a day feeding, depending on the season. They are most active at dawn and dusk, but relatively inactive during the middle of both the day and night when they are resting. They eat mostly grasses and shrubs but will occasionally eat other plants. Predators include eagles, which take the young, dingos, foxes, crocodiles, and humans. Black wallaroos use camouflage to hide from predators. They are also quick and agile and can to escape from predators to a hiding place.

Black wallaroos engage in year-round breeding and employ delayed implantation (a condition in which a fertilized egg reaches the uterus but delays its implantation in the uterine lining, sometimes for several months). The gestation period ranges from 31 to 36 days; longer if delayed implantation is implemented. Similar to other wallaroos, breed continously throughout the year under good conditions. Females often increase their area of activity in order to attract the largest most dominant male in that area. Reproduction is often tied to lactation, which depends on the availability of food resources. |=|

Young are altricial, meaning they are relatively underdeveloped at birth. Parental care is carried out by females. Young are only a few centimeters in length when born and find their way to the mother's pouch and attach themselves to a nipple. Young are attached to the nipple for about four months of age, during which time the mother may be carrying another embryo in the uterus in embryonic diapause. After the young detach themselves from the nipple, they continue to live in the pouch, but the mother is able to give birth to another baby, which resumes uterine development after the embryonic diapause stops. In this way, female wallaroos are able to support two different aged joeys in the pouch simultaneously. Young emerge from the pouch after about six months. The mother can control the opening of the pouch with muscles to either keep the joey inside when the mother is alarmed or to get the joey to exit the pouch. Even after the joey is not living in the pouch anymore, it returns to the pouch to suckle for many months.

Antilopine Wallaroos

Antilopine wallaroos(Osphranter antilopinus or bernardus Macropus) are known as antilopine kangaroos and antilopine wallabies, They live grassy plains and woodlands and are gregarious, unlike other wallaroos which are solitary. Antilopine wallaroos have lived in the wild up to 16 years of age, while the longest lived antilopine wallaroo in captivity was 15.9 years of age. [Source: Kurt Bonser, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Antilopine wallaroos inhabit savanna woodlands throughout the northern, tropical regions of Australia, from the Kimberley to the Gulf of Carpentaria. They are also found in the Cape York Peninsula. During the day they hang out in shaded wooded areas to avoid the hot sun. At dusk they graze (eat grass or other low-growing plants) in grasslands and at dawn return to wooded areas. During the cooler wet season, antilopine wallaroos may also graze during the day, but they seek shelter from rain in wooded areas. Eastern populations have been found on slopes and tops of small hills. They may also be found in valleys and low-lying depressions on the floodplains of major rivers, especially in moist areas populated with short green grass. Northern populations favor sites with permanent water where fires occur late in the season.

Antilopine wallaroos range in weight from 15 to 70 kilograms (33 to 154 pounds) and range in length from 1.5 to 1.9 meters (4.9 to 6.2 feet). Paws and feet of both sexes are white on the ventral side and are black tipped. Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is very much present: Males are much larger than females. Males weigh up to 70 kilograms (154 pounds) while females usually weigh 15 to 30 kilograms (33 to 66 pounds) Sexes are colored or patterned differently with the male being more colorful.

Adult males are usually a reddish tan color while female are brownish tan in the back and hind parts and usually have gray heads and shoulders. Females also have white tips on the back of their ears. Adult males have a distinct swelling of the nose above the nostrils that is possibly used for cooling. Females develop their pouches after about 20 months. In joeys, the fur coloration is apparent after six to seven months. The shape of a female joey’s head is more petite than the male joey’s.

Antilopine wallaroos are not endangered. They are designated as a species of least concern on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List and have no special status on the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). They have been traditionally been hunted and stil; are hunted the Aboriginal people of Australia. Because they graze in grasslands, Antilopine wallaroos may compete with cattle for forage. They have likely benefited from human conversion of forests to agricultural land and grasslands.

Antilopine Wallaroo Behavior

Antilopine wallaroos are saltatorial (adapted for leaping), crepuscular (active at dawn and dusk), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), sedentary (remain in the same area), social (associates with others of its species; forms social groups). The home territories of males are up one square kilometer (0.38 square mile), while the home ranges of females are generally les than 20 hectares (50 acres). [Source: Kurt Bonser, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Antilopine wallaroos are very social animals. Older males, however, are often solitary. Groups (mobs) of males and females are often seen together. Both male and female antilopine wallaroos groom each other. After joeys reach their mother's pouch, the mob sexually segregates; the males separate into small "bachelor groups". In turn, females form large groups of females and their young. Antilopine wallaroos move to and from grazing grounds and return to the same area or "camp" repeatedly, both in groups and individually. Males also fight frequently. Antilopine wallaroos communicate with vision, touch and sound and sense using vision, touch and chemicals usually detected with smell. Before fighting, males make a hissing sound and toss their heads. They also hiss, and stamp their feet, when alarmed.

Antilopine wallaroos are herbivores (eat plants or plants parts), and their diet is mainly composed of grass. They seek areas with short grass, like low tussock grass, or where tall grass has been burnt and reduced to shoots. There are no known predators of antilopine wallaroos other than humans.

Antilopine Wallaroo Mating, Reproduction and Offspring

Unlike most kangaroos and wallaroos, Antilopine wallaroos engage in seasonal breeding. Mating occurs at the beginning of the wet season, usually around December. The gestation period ranges from 34.1 to 35.9 days, with one offspring being born. [Source: Kurt Bonser, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Young are altricial, meaning they are relatively underdeveloped at birth. Parental care is provided by females. The post-independence period is characterized by the association of offspring with their mothers. The average weaning age and time to independence is 15 months. Females reach sexual or reproductive maturity at 16 to 20 months; males do so at two years.

Females come into estrus within a few days of each other. Although estrus of females does not seem to be related to the age of their young (joeys), estrus always occurs after the permanent emergence of the joey. An increased amount of fighting by male antilopine wallaroos has been observed near the beginning of the breeding season. To attract a mate, a male sniffs the female’s cloacal region, then shows his ventral surface and erect penis. Male antilopine wallaroos lose interest in their mate and young once the neonate reaches its mother's pouch.

After birth the neonate climbs into the mother's pouch, much like all macropods. After about 20 weeks, the joey begins to emerge from the pouch. At about six months the joey completely comes out of the pouch for the first time, and at about 37 weeks the mother does not allow the joey back in the pouch. A joey is gradually weaned, feeding less and less from its mother until about 15 months after birth.

Once all neonates reach their mother's pouch, the group sexually segregates; large males form small groups while females and young remain together in large groups. Even after weaning, young antilopine wallaroos maintain a close relationship with their mother, resting together and grooming each other.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org , National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, David Attenborough books, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2025