Home | Category: Animals / Kangaroos, Wallabies and Their Relatives

WALLABIES

Some wallaby species: 4) Grey Forest Wallaby (Dorcopsis luctuosa); 5) Brown Forest Wallaby (Dorcopsis muelleri); 6) Macleay’s Forest Wallaby (Dorcopsulus macleayi); 7) Small Forest Wallaby (Dorcopsulus vanheurni); 8) Bridled Nail-tailed Wallaby (Onychogalea fraenata); 9) Northern Nail-tailed Wallaby (Onychogalea unguifera)

Wallaby are a small or middle-sized macropod native to Australia and New Guinea, with introduced populations in New Zealand, Hawaii, the United Kingdom and a few other places. They belong to the same taxonomic family as kangaroos and sometimes the same genus, but kangaroos are specifically categorised into the four largest species of the family. The term "wallaby" is an informal designation generally used for any macropod that is smaller than a kangaroo or a wallaroo that has not been designated otherwise. The name wallaby comes from Dharug walabi or waliba, an Aboriginal name. In the past they were called brush-kangaroos. [Source: Wikipedia]

Wallabies come in many sizes and varieties. The most common species are the agile wallaby, red-necked wallaby, and swamp wallaby. Many reach a length of about of a little less than two meters (six feet), including their tails, when fully grown. Their powerful hind legs are used for hopping at high speeds and jumping great heights and distances, and also to deliver vigorous kicks to fend off potential predators. Swamp wallabies wade through wetlands. The spectacled hare-wallaby was given its name by European settlers who though the animal looked like a hare when it was was in a crouched position. Dwarf wallabies, native to New Guinea, are the smallest known wallaby species and one of the smallest known macropods. They are about 46 centimeters (18 inches) from their nose to the end of their tail, and weighs about 1.6 kilograms (3.5 pounds).

The terms for wallabies are roughly the same as those for kangaroos. Young are referred to as "joeys". Adult male wallabies are called "bucks", "boomers", or "jacks". Adult females are called "does", "flyers", or "jills". A group of wallabies is called a "mob", "court", or "troupe". Scrub-dwelling and forest-dwelling wallabies are known as "pademelons" (genus Thylogale) and "dorcopsises" (genera Dorcopsis and Dorcopsulus), respectively.

Wallabies are widely distributed across Australia, particularly in more remote, heavily timbered, or rugged areas, less so on the great semi-arid plains that are better suited to the larger, leaner, and more fleet-footed kangaroos. Wallabies are herbivores (eat plants or plants parts) and consume a wide variety of grasses, vegetables, leaves and other foliage. Some have adapted to agricultural and urban areas. Wallabies may cover vast distances when foraging.. Mobs often congregate around the same water hole during the dry season.

Wallabies have been hunted for meat and fur and still are in some places. They may be prey to dingoes, domestic and feral dogs, feral cats, and red foxes. Many wallabies are killed by vehicles as they often feed near roads and urban areas.

RELATED ARTICLES:

KANGAROOS AND WALLABIES (MACROPODS): CHARACTERISTICS, HISTORY, POPULATIONS ioa.factsanddetails.com

WALLABY SPECIES ioa.factsanddetails.com

WALLABY SPECIES OF SOUTHWEST AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

WALLAROOS: SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

ROCK-WALLABIES: SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

BRUSH-TAILED ROCK-WALLABIES: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

HARE-WALLABIES: SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

QUOKKAS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION, ROTTNEST ioa.factsanddetails.com

FOREST WALLABIES (DORCOPSIS): SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

PADEMELONS: SPECIES CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

KANGAROO BEHAVIOR: FEEDING, REPRODUCTION, JOEYS ioa.factsanddetails.com

KANGAROOS HOPPING: MOVEMENTS, METABOLISM AND ANATOMY ioa.factsanddetails.com

MARSUPIALS: HISTORY, EVOLUTION, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

MARSUPIALS IN AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

MARSUPIALS IN AUSTRALASIA (AUSTRALIA, NEW GUINEA, NEARBY ISLANDS) ioa.factsanddetails.com

Types of Wallabies

Wallabies are not a distinct genetic group. Nevertheless, they fall into several broad categories.

The seven species of pademelons or scrub wallabies (genus Thylogale) of New Guinea, the Bismarck Archipelago, and Tasmania are small and stocky, with short hind limbs and pointed noses. The three species (two extant and one extinct) of nail-tail wallabies (genus Onychogalea) have a horny spur at the tip of the tail — a distinguishing feature whose purpose is unknown. The seven species of dorcopsises or forest wallabies (genera Dorcopsis (four species, with a fifth as yet undescribed) and Dorcopsulus (two species)) are all native to the island of New Guinea.

The swamp wallaby (genus Wallabia) is the only species in its genus. Quokkas are also monotypic. Also known as short-tailed scrub wallabies (genus Setonix), they are now restricted to two offshore islands of Western Australia which are free of introduced predators.

The 19 known species of rock-wallabies (genus Petrogale) live among rocks, usually near water; two species in this genus are endangered. Rock wallabies are relatively small, about one meter (three feet long) and weigh around nine kilograms (20 pounds). They move around cliffs and ledges with agility of a mountain goat. When threatened they can escape by hopping 15 to 20 feet "from one precarious perch to another". Rock wallabies have been compared with goats and fulfill as similar niche. They are adapted for rugged terrain with modified feet that can grip rocks with skin friction rather than dig into soil with large claws. The relationship between several of the 19 species is not well understood.

The two living species of hare-wallabies (genus Lagorchestes) are small animals that have the movements and some of the habits of hares. The banded hare-wallaby (Lagostrophus fasciatus) is thought to be the last remaining member of the once numerous subfamily Sthenurinae, and although once common across southern Australia, it is now restricted to two islands off the Western Australian coast which are free of introduced predators. It is not as closely related to the other hare-wallabies (genus Lagorchestes) as the hare-wallabies are to the other wallabies.

Parma wallabies (Notamacropus parma) are the smallest kangaroo or wallaby. About the size of a chubby cat, adults are about 50 centimeters (1.6 feet) tall, with a tail between 40 and 55 centimeters long. They live in the bush of southeastern Australia in mobs with around a dozen members and eat leaves, shoots and grasses.

Brush Wallabies

There are several species of wallabies that have "brush" in their name. The most commonly referred to is the Brush-tailed rock-wallaby (Petrogale penicillata), which is a type of rock-wallaby found in eastern Australia. Another species is the western Brush wallaby (Notamacropus irma), also known as the black-gloved wallaby, found in southwestern Western Australia.

The term brush wallaby is does not define a taxonomic group. By some reckonings agile wallabies and the red-necked wallabies — among the wallabies most closely related to kangaroos and wallaroos and, aside from their size, look very similar — are considered brush wallabies. These are the ones most frequently seen, particularly in the southern states. According to this reckoning, which is not widely accpeted, there are nine species (eight extant and one extinct) of brush wallaby. Their head and body length is 45 to 105 centimeters (18 to 41 inches) and the tail is 33 to 75 centimeters (13 to 30 inches) long.

Brush-tailed rock-wallabies are fairly plentiful. They are widespread in the Great Dividing Range in eastern Australia (they are described in the rock wallaby section). Black-striped wallabies are considered brush wallabies. One of the brush wallaby species, the dwarf wallaby (Notamacropus dorcopsulus), native to New Guinea, is the smallest known wallaby species and one of the smallest known macropods. They are about 46 centimeters (18 inches) from nose to the end of the tail, and it weighs about 1.6 kilograms (3.5 pounds).

Wallaby Characteristics

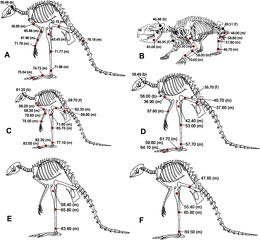

As with other macropods like kangaroos, the hind limbs of wallabies are adapted for fast, powerful, hopping. The fourth digit of the hind feet bears the bulk of the energy transferred from the leg to the ground during hopping. In addition to hopping, macropods engage in a slower — 'pentapedal' — form of locomotion, in which the tail is used in conjunction with the forelimbs to support the weight of the body while the hind legs are swung forward. Their tails serve as a counterbalance when hopping, a kind of chair when standing still and a fifth limb when moving slowly. [Source: Natalie Morningstar, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

The hind legs are larger than the forelimbs and specialized for leaping. The significantly smaller forelimbs contain five digits and are used for eating and slower movements. The big toe is absent in the hindlimbs which are syndactylous (with toes fussed together) and elongated for use in rapid bipedal motion. The fourth toe is the longest and the most specialized digit of the hindfoot. This, along with the loss of the big toe are adaption for hopping.

Wallabies and kangaroos are herbivores (eat plants or plants parts) and mainly eat grass. Wallaby stomachs are divided into four chambers that enable them to ferment and extract nutrients from high-fiber food sources, such as grasses. They have the ability to move the lower jaw forward and backward, maximizing the shredding effect. Like all marsupials, females have a pouch in the skin of the abdomen in which their young live and nurse.

Wallabies are diprotodont marsupial (with only two large, forward-facing incisors in their lower jaw) with a bilophodont occlusal pattern (Bilophodont molars are a specific type of molar tooth morphology characterized by having two parallel ridges, or 'lophs,'). Females have pouches that open to the outside and contain four mammae. Wallabies also have a powerful tail that is used mostly for balance and support.

Wallaby Behavior

Wallabies are terricolous (live on the ground), saltatorial (adapted for leaping), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary) and sedentary (remain in the same area). Most are nocturnal (active at night) or crepuscular (active at dawn and dusk) but some are diurnal (active during the daytime). They can be solitary or social. The latter tend to live in small groups but can gather in large mobs, sometimes with other species, at good feeding spots. Some have dominance hierarchies (ranking systems or pecking orders among members of a long-term social group, where dominance status affects access to resources or mates). [Source: Peter Hundt, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

The main natural enemies of wallabies, introduced red foxes are dingoes and birds of prey. Dingoes catch and hunt wallabies and kangaroos. Wallabies defend themselves by kicking with their hind legs. Some species of wallaby issue alarm calls and thump their feet to alert others of danger. When attacked by a dingo, a tamar wallaby is often trapped with its back up against a tree. It then attempts to strike the dingo with its forepaws, and finally thrusts its hindlimbs forward, aiming for the attacker's belly. The force of the hindlimbs or gashes made by a wallaby's sharp claws can seriously injure a dingo. [Source: Annette m. Labiano-Abello, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

The fighting style of most wallabies and kangaroos consists of the use of the forelimbs to grab and hold an opponent around the head, neck or shoulders. They use their hindlimbs to kick forward and use their tails for balance and support.

Wallaby Communications

Wallabies sense and communicate with vision, touch, sound and chemicals usually detected by smelling. They are known to transmit information through scent cues, especially when females are in estrus. Males determine the readiness of females to mate based upon their smell. In addition, there is some visual and tactile communication during mating, based upon chasing behavior and the mating process itself.

According to Animal Diversity Web: Wallabies often communicate with hoarse growls and cough-like vocalizations, particularly to communicate aggression. It has been noted that several wallabies also express alarm by stamping their feet on the ground. Soft clucking is common in males attempting to attract mates and for females interacting with their young. The use of pheromones (chemicals released into air or water that are detected by and responded to by other animals of the same species) to check females as they approach estrus has also been observed in Tammar wallabies. [Source:Natalie Morningstar, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Wallabies live in fairly organized societies, in which males compete for hierarchical mating rights. Males also engage in an olfactory courtship ritual with the females. After a female gives birth, mother/young interaction is minimal — the offspring is not assisted into the pouch and interaction is limited to cleaning the joey. Once the offspring leaves the pouch, however, the mother and young will communicate by clucking and grunting, play, and will groom each other.

Wallaby Mating, Reproduction and Offspring

Most wallabies engage in year-round breeding but some engage in seasonal breeding Gestation periods tend to be short — between 20 and 40 days. Typically one joey is born. Females of some species are capable of producing three offspring at different times per year . The weaning age is usually several months; often young continue nursing after they have left the pouch.

Young are extremely altricial, meaning they are relatively underdeveloped at birth. Often they weigh around a gram or less at birth and complete their development inside their mother's pouch, attached to her nipple. Most or all of the parental care is provided by females. Males may be involved in protecting a group with young but their role in child rearing usually extend much beyond that.

Many wallabies employ embryonic diapause (temporary suspension of development of the embryo). Also known as "delayed birth" because embryonic development is temporarily posponed, it is employed when conditions for birthing are not good — such as weather being too hot, when not much food is available or when a female is already has a joey in her pouch — and delays birth until better conditions are available. A female that is nursing a joey in her pouch may have a dormant embryo in its uterus. Then, when the joey stops nursing, the embryo resume its development. [Source: Annette M. Labiano-Abello, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Uterine gestation is very brief, and much of the development of the embryo takes place in the pouch outside of the uterus. The pouch contains the nipples. The birthing process starts with the newborn leaving the cloaca and freeing itself from the fetal membranes. Instinctively, led by sense of smell and gravity, it makes its way to the pouch. Once in the pouch, the newborn attaches its mouth to a single teat, from which the newborn gets milk high in fat and nutrients.

Healthy Wallabies More Likely to Give Birth to Boys

Healthy female wallabies are more likely to give birth to sons than daughters, according to a November 2009 study involving tammar wallabies published online in the journal Biology Letters. The research, led by Dr Kylie Robert of the University of Western Australia, supports the as yet unproven Trivers-Willard hypothesis that mothers will give birth to different sexes depending on their condition. Uneven sex ratios are seen in many mammal species, including humans, but despite decades of research and debate it is still poorly understood why they occur, says Robert. [Source: Fiona MacDonald, ABC, November 24, 2009]

Fiona MacDonald of ABC wrote: The Trivers-Willard hypothesis suggests that mothers in better condition give birth to boys, because strong males will have more mating success, while females are a safe option if the mother can't ensure her baby will be well fed. "In wallaby populations, females will always be mated with regardless of how strong and healthy they are," says Robert. "Weak males, on the other hand, are unlikely to have much reproductive success as they will be outcompeted by stronger males."

By swapping mothers' joeys for offspring of the other sex, Robert and her team are the first to provide experimental support for the theory. The research involved 32 tammar wallaby mothers from Tutanning Nature Reserve in Western Australia. After all joeys were removed from their pouches, mothers that birthed a son were given a daughter to raise and vice versa, while a control group of mothers had their original offspring returned to them. The study found that mothers who had originally birthed sons successfully raised more offspring to weaning, regardless of sex, than mothers who originally had daughters, proving that they could better provide for their children.

The fact that marsupial mothers invest the majority of their resources after they've given birth, when their offspring is in the pouch, make them ideal to explore the reasons behind sex allocation, says Robert. "Most mammals invest a lot into their offspring before they give birth, so we can't manipulate these pregnancies to find out which mothers are putting in the most."

Professor Andrew Cockburn of the Australian National University, an expert on sex allocation in mammals and who was not involved with the study, believes it is significant research that paves the way for future work. "What they've done is just the first step," he says. "More research is needed to tease apart the importance of maternal investment in male and female offspring, but they've proved that the marsupial system will be useful in finding out more about sex allocation."

The finding is significant for breeding programs that aim to restore populations of endangered kangaroos and wallabies, Roberts says. "Animals bred in captivity are in good condition and often produce predominately one sex - usually males." "If we can learn the physiological signals that tell a mother whether they should have a boy or a girl then we could reproduce them and optimise the sex ratio for successful breeding programs."

Wallabies Do Freestyle in the Womb

Wallaby embryos start doing the 'Australian crawl' — the style of swimming used in the Olympic freestyle events — while still in their mother's womb, high-resolution ultrasounds reveal, according to a study published in in March 2013 in Nature Scientific Reports. provides a unique insight into the development of marsupials. [Source: Genelle Weule, ABC, March 18, 2013] . The paddling movements prepare the tiny blind and hairless embryo for the journey to its mother's pouch when it is born, says study co-author Dr Geoff Shaw from the University of Melbourne. "They've got this glorious 'Australian crawl'. The four limbs go in this circular pattern on both sides - left, right, left, right, swinging their arms around which propels them across the fur. They actually start those sorts of movements ... three days before [birth] when they really are a very early embryo.” Marsupials have “all evolved from the same origins and the physiological needs that they have are pretty much the same. But given how immature they are at the time they are born, to find that they are doing quite complex controlled movements three days before birth is just astonishing."

Marsupials have very rapid development periods compared to other mammals. They have ultra-short pregnancies and give birth to very immature, almost embryonic young Tammar wallabies are pregnant for around 26 days before giving birth to a joey that weighs around one gram that crawls unassisted to its mother's pouch. During pregnancy the embryo is still a "hollow ball" until about day 18, and it is only in the last eight days that the cells transform into an identifiable embryo, says Shaw. "Humans begin co-ordinated limb movements about week 12 of pregnancy. When wallabies begin their coordinated movements, three days before birth, they are developmentally equivalent to about a four to five-week old human foetus," says Shaw.

To study the development of the wallaby embryo, Shaw and colleagues including researchers from the Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research in Germany, selected a group of 20 wallabies and synchronised their pregnancies. They then monitored the wallabies over their 26-day active gestation phase with daily ultrasounds. "About the time we were expecting them to give birth we even watched them 24 hours a day to see when they actually gave birth to have that extra bit of data," says Shaw. Not only did the ultrasounds show the embryo moving while in the uterus, but from halfway through the pregnancy the lining of the uterus showed strong rolling movements. "That probably stirs things up around the embryo and makes sure the nutrition gets to where it should be around the baby," says Shaw.

Shaw says the findings are likely to apply to other marsupials, but these would be much harder to study. "You need a very high resolution ultrasound if we deal with smaller marsupials than the wallaby. Some of them have got absolutely minute babies that are able to climb when they are born and attach to the teat. Like the honey possum from Western Australia, for example, their babies are a ten one thousandths of a gram when they're born. They look like a grain of rice."

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org , National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, David Attenborough books, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2025