Home | Category: Animals / Nature, Environment, Animals / Kangaroos, Wallabies and Their Relatives / Marsupials

MARSUPIALS

Marsupials (Scientific name: Metatheria) are mammals with pouches who bear offspring at an earlier stage of development than other mammals. They are different from eutherians, (placental mammals), the largest mammal group on earth, which includes dogs, whales, lions and humans. Marsupial infants are born earlier and raised in a pouch at a time when they would still be embryos inside the placenta of a mammalian mother. While some marsupial live only one to a few years, some species, such as coarse-haired wombats, have lived up to 26 years in captivity.

The relatively underdeveloped young grow almost exponentially in the mother's pouch. "The young are born alive, but they're very poorly developed," Robin Beck, a lecturer in biology at the University of Salford in the United Kingdom, told Live Science. "They basically crawl to their mother's nipple, which is often in a pouch, and they basically clamp on the nipple and stay there, feeding on their mother's milk for long periods of time — usually, several months." [Source: Laura Geggel, Live Science, March 3, 2019]

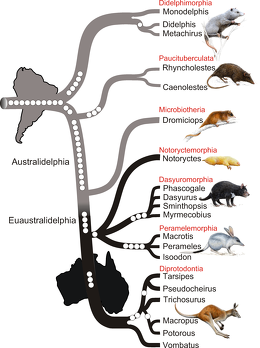

Marsupials range in range from a few grams in the long-tailed planigale to several tonnes in the extinct Diprotodon. The word marsupial comes from marsupium, the technical term for the abdominal pouch. It, in turn, is borrowed from the Latin marsupium and ultimately from the ancient Greek mársippos, meaning "pouch". Marsupials constitute a clade stemming from the last common ancestor of extant Metatheria, which encompasses all mammals more closely related to marsupials than to placentals. The evolutionary split between placentals and marsupials occurred 125-160 million years ago, in the Middle Jurassic-Early Cretaceous period. [Source: Wikipedia]

Marsupials are currently classified into seven orders and approximately 20 families, with around 335 species, according to ScienceDirect.com. The number of genera is not explicitly stated, but one source lists 83 genera. Sadly, these days many of these unique animals are threatened by unexplained outbreaks of disease — and it seems highly plausible that these are connected somehow with humans.

The first marsupial genome to be sequenced was that of the grey short-tailed opossum (Monodelphis domestica) from South America. The sequencing was completed in 2006 and published in 2007, with research led by Kerstin Lindblad-Toh at the Broad Institute. This project provided valuable insights into marsupial genetics and evolution, particularly in comparison to placental mammals. The research revealed that much of the genetic divergence between marsupials and placentals occurred in non-coding sequences rather than protein-coding genes, challenging previous assumptions. [Source: Google AI]

RELATED ARTICLES:

MARSUPIALS IN AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

MARSUPIALS IN AUSTRALASIA (AUSTRALIA, NEW GUINEA, NEARBY ISLANDS) ioa.factsanddetails.com

KANGAROOS AND WALLABIES (MACROPODS): CHARACTERISTICS, HISTORY, POPULATIONS ioa.factsanddetails.com

KANGAROO BEHAVIOR: FEEDING, REPRODUCTION, JOEYS ioa.factsanddetails.com

KOALAS: CHARACTERISTICS, EVOLUTION, HISTORY, ANATOMY, POPULATIONS, DIET ioa.factsanddetails.com

KOALA BEHAVIOR: TREES, COMMUNICATION, REPRODUCTION, YOUNG ioa.factsanddetails.com

WALLAROOS: SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

WALLABIES: TYPES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

WALLABY SPECIES ioa.factsanddetails.com

ROCK-WALLABIES: SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

PADEMELONS: SPECIES CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

TREE-KANGAROOS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

Marsupial Species, Diversity and Their Distribution

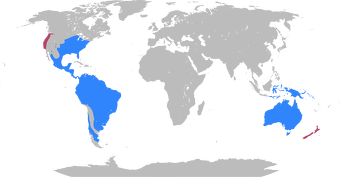

Marsupials are very ancient animals. They are very diverse in body form, and occupy an enormous range of ecological niches. There are around 334 species of marsupials, with around 70 percent of them in There are approximately 270 marsupial species found in the Australasian region, which includes Australia, New Guinea, Indonesia, and the Solomon Islands.

monito del monte (Dromiciops gliroides), a South American marsupial more closely related to Australian marsupials than other South American marsupials

Outside Australasia, the largest number of marsupials are found in Central and South America (around 120 species). There are no native marsupial species in Europe and Asia, outside Indonesia. There is only one species of marsupial native to North America: the Virginia opossum. The main reason for this distribution is that before 125 million years when the parts of supercontinent Gondwana was still close together and partly connected Australia, Antarctica and South America were semi-joined together while Africa was largely separated and Europe, Asia and North America were far away.

Radiations of marsupials took place in Australasia and Central and South America tens of millions of years ago when there were few placental competitors. Present marsupial species are very diverse. Some have remarkable parallels with placental mammals (such as marsupials with similar morphologies and life histories as moles, anteaters, shrews, primates and carnivores). Other marsupials have life histories and morphologies that seem to have parallels with without placental mammals — for example, kangaroos. [Source: Matthew Wund and Phil Myers, Animal Diversity Web (ADW)|=|]

In South America parallel radiations of large placental herbivores may have denied these herbivores niches to marsupials but marsupials there filled many carnivore niches (including a sabretooth marsupial "cat") and many rodent-like forms. In both North America and South American the of placental mammals is correlated with a decline in number and diversity of marsupials. However, it is unclear whether placental mammals caused the disappearance of marsupials through competition or the apparent pattern of replacement is the result of random historical events.

Earliest Marsupials

The earliest known marsupials, or their close ancestors, are dated to around 125 million years ago, during the Early Cretaceous period. Fossil evidence suggests they originated in North America and China. Sinodelphys szalayi, a mouse-sized, tree-climbing animal found in China, is the oldest known marsupial ancestor. A 2022 study provided strong evidence that the earliest known marsupial was Deltatheridium, which lived 83.6 to 72.1 million years ago in Mongolia This study placed both Deltatheridium and Pucadelphys as sister taxa to modern large American opossums. [Source: Wikipedia]

Marsupials spread to South America from North America during the Paleocene Period (66 million to 56 million years ago), possibly via the Aves Ridge in the present-day Caribbean. Northern Hemisphere marsupials were of low morphological and species diversity compared to contemporary placental mammals, and eventually became extinct during the Miocene Period (16 million to 11.6 million years ago). DNA evidence supports a South American origin for marsupials, with Australian marsupials arising from a single Gondwanan migration of marsupials from South America, across the Antarctic land bridge, to Australia.

Laura Geggel wrote in Live Science: Ancient marsupials appeared to flourish in North America, populating what was then the supercontinent Laurasia with about 15 to 20 different marsupial species, all of which are now extinct, Beck said. It's unclear why these marsupials did well. But for some reason, at about the time that the nonavian dinosaurs went extinct, about 66 million years ago, the marsupials made their way down to South America. At that time, North and South America weren't connected as they are today. But the two continents were very close, and a land bridge or a series of islands may have linked them. This connection allowed all kinds of animals to expand their stomping grounds. [Source: Laura Geggel, Live Science, March 3, 2019]

Dispersal of Marsupials

The two main groups of marsupials, Australidelphia and Ameridelphia, occurred in South America after marsupials dispersed from North America. Australidelphians are Australian marsupials, distinguished by a continuous lower ankle joint. Ameridelphians are American marsupials, distinguished by a separated lower ankle joint. Australidelphia eventually migrated into Antarctica and then into Australia when these continents were connected in the giant landmass Gondwanaland. Dasyuromorphs are a part of Australidelphia. The primary radiation of marsupials occurred in Antarctica[Source: Nicole Armbruster Chad Nihranz and Elizabeth Colvin, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Laura Geggel wrote in Live Science: Once in South America, marsupials and their close relatives had a field day, diversifying like crazy within 2 million to 3 million years after arriving, Beck said. For instance, marsupials and their close relatives evolved into bear- and weasel-size carnivores, and one even evolved saber teeth. Others evolved to eat fruits and seeds. "What's happening in South America is they're evolving to fill the kinds of niches that in the northern continents certainly were filled by placental mammals," Beck said. Many of these marsupials went extinct between then and now, but South America is still a marsupial hotspot today. There are more than 100 species of opossums, seven species of shrew opossums and the adorable monito del monte (Dromiciops gliroides), whose Spanish name translates to "little monkey of the mountain." [Source: Laura Geggel, Live Science, March 3, 2019]

On a side note, within the last 1 million years, one of South America's opossums traveled north and now lives in North America. This is the Virginia opossum (Didelphis virginiana), the only marsupial living north of Mexico, Beck said. Also, opossums belong to a different order than possums. Possums are native to Australia and New Guinea, are closely related to kangaroos, and have a number of anatomical differences, such as enlarged lower incisors, that the South American opossum lacks, Beck said.

Marsupial Habitats and Ecosystems

Marsupials are very adaptable and flexible and live a wide range of habitats in temperate and tropical climates in freshwater areas, deserts, semi-deserts, savannas grasslands, chaparral, forests, rainforests, scrub forests and mountains. They are found around lakes, ponds, rivers, streams, wetlands and swamps as well as urban, suburban and agricultural areas. .[Source: Matthew Wund and Phil Myers, Animal Diversity Web (ADW)|=|]

Marsupials occupy an enormous variety of terrestrial habitats throughout Australia, Australasia (excluding New Zealand) and Central and South America. They have evolved to fill many niches in many habitats. Many species are fully terrestrial, many are arboreal (live mainly in trees), and at least one species, yapoks (water opossums) of South American, is semi-aquatic.

With their great diversity of food habits, behavior and habitat use, marsupials can substantially impact their communities and ecosystems in a variety of ways. They may help pollinate plants, distribute seeds, or control pest populations. Most species are prey for other species and thus are an important component of many food webs. Species that dig burrows (e.g. wombats and marsupial moles) create habitat for other organisms and/or help aerate soil. Parasites of marsupials are as diverse as their hosts.

Marsupial Characteristics

Marsupials, like all mammals, are endothermic (use their metabolism to generate heat and regulate body temperature independent of the temperatures around them) and homoiothermic (warm-blooded, having a constant body temperature, usually higher than the temperature of their surroundings). Marsupials in general tend to have lower basal metabolic rates than other mammals. Some authors have suggested that this may be related to their saltatorial (adapted for leaping) locomotion that many marsupials employ.

Matthew Wund and Phil Myers wrote in Animal Diversity Web: Marsupials differ from placental mammals in a number of important and obvious ways. The palate of marsupials is usually "fenestrated," that is, it contains large gaps or spaces in its bony surface. The angular process of the dentary is inflected (bent) medially in almost all marsupials. The braincase is small and narrow. It houses a relatively small and simple brain compared to that of similar-sized placental mammals. The jugal (bony arch of the cheek) is large, extending posteriorally so that it contacts, and forms part of, the glenoid fossa (shallow, depressed area on a bone). The lacrimal canal (tear duct) is slightly anterior to the orbit around the eyes so that it opens on the surface of the face rather than inside the orbital space. The bullae (bones are the ears) are sometimes not ossified. When they are, they are formed largely by extensions from the alisphenoid (bones behind the eyes). [Source:Matthew Wund and Phil Myers, Animal Diversity Web (ADW)|=|]

Tracking-Marsupial-Evolution-Using-Archaic-Genomic-Retroposon-Insertions: In genomes there is an intricate association between SINE elements and the much longer long interspersed elements (LINEs), as the replication of SINEs ultimately depends on the enzymatic machinery of LINEs; Using the TinT method in marsupial genomes, we detected independent SINE-LINE associations that overlapped in time; The L1 system dominates SINE retropositions in Didelphimorphia (SINE1_Mdo, SINE1a_Mdo); The retroposon-like transposable element (RTE) system predominates in the lineage leading to the kangaroo (WALLSI1-4), and LINE2- (MIR, MdoRep1, THER1_MD) and LINE3- (MIR3) mobilized SINE systems are present in both lineages and were active over long periods of marsupial evolution; Experimental screening revealed the activities of two, sometimes three, SINE-LINE associations at some deep nodes; For instance, at least three SINE-LINE associations were active in the common ancestor of the four Australasian orders (RTE-WALLSI1a/L1-WSINE1/L2-MIR_Mars) (Figure S1); In most other mammalian genomes, only one SINE-LINE group was active at a time; thus, the discovery of multiple groups may indicate a long branch and/or overlapping activity; As several different SINE-LINE systems were also active at the Australidelphia node (RTE-Mar1a,b,c_Mdo/L1-WSINE1/RTE-WALLSI3), we favor overlapping, extended activity of retroposition systems in marsupials; The extended presence of diverse SINE transposition systems found in marsupial genomes is unique in mammals; Twenty-four SINE subfamilies were extracted from genomic data of M; domestica and M; eugenii to screen for nested insertions, revealing information about their relative activity periods; Elements shown in black denote L3-, those in blue L2-, those in green RTE-, and those in red L1-mobilized SINEs; Ovals represent the 50% probability of the activity distribution and horizontal lines indicate the 90% probability of the activity distribution; Relative time axes are given at the bottom

Tooth form varies considerably among species of marsupials, but an easy and reliable character for recognizing members of the group is that the number of incisors in the upper jaw is different from the number in the lower (except in one family, the Vombatidae). The number is equal in most (but not all) placental mammals. Also, the maximum number of incisors (seen in several families) is 5/4, in contrast to 3/3 in placentals. The number of premolars and molars also differs between the groups (3/3 4/4 in marsupials, 4/4 3/3 in placental mammals), and the pattern of tooth replacement (milk teeth by adult teeth) differs, but these traits are difficult to use to recognize specimens.

Postcranial skeletons (skeleton excluding the skull) of marsupials differ from those of placental mammals in that modern marsupials have epipubic bones (bones that that project forward from the pubic bones of the pelvic girdle) in the body wall, projecting anteriorally from the pelvis. Epipubic bones are vestigial in recently extinct thylacines and were absent in at least one extinct group. The presence of epipubic bones is shared with monotremes.

Distinguishing among most of the orders and families of modern marsupials is not difficult. Two frequently-used characteristics are the conformation of the feet, and the number and position of the lower incisors. The second and third toes of syndactylous species (with digits, typically fingers or toes, that are fused or webbed together) .are mostly enclosed in a sheath of skin and appear fused, except for the claws. Members of the orders Peramelemorphia and Diprotodontia are syndactylous. Others have separate toes, sometimes referred to as polydactylous. Members of the Diprotodontia and Paucituberculata have a pair of enlarged, forward-projecting (procumbent) lower incisors, a condition called diprotodonty. Other groups are polyprotodont, with numerous small and unspecialized lower incisors. Marsupial moles (Notoryctemorphia) are an unusual group, probably because of their extreme specialization to a fossorial (engaged in a burrowing life-style or behavior, and good at digging or burrowing), mode of life. Their incisor morphology is not clearly diprotodont or polyprotodont and their feet are neither polydactylous nor syndactylous.

Marsupial Behavior

Marsupial can be arboreal (live mainly in trees), scansorial (good at climbing), cursorial (with limbs adapted to running), terricolous (live on the ground), fossorial (engaged in a burrowing life-style or behavior, and good at digging or burrowing), saltatorial (adapted for leaping), natatorial (equipped for swimming), diurnal (active during the daytime), nocturnal (active at night), crepuscular (active at dawn and dusk), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), territorial (defend an area within the home range), and social (associates with others of its species; forms social groups). [Source: Matthew Wund and Phil Myers, Animal Diversity Web (ADW)|=|]

Marsupial means of locomotion may include walking, gliding, hopping, running and swimming. Some marsupials glide like flying squirrels. Many are solitary. Most are nocturnal, a primary reason why tourist don't see many species. A large number tend have a low resting metabolic rate which helps them survive in Australia's hot, dry weather. Hibernation (when normal physiological processes are significantly reduced, thus lowering the animal's energy requirements) is practiced by some during the winter. Others remain active throughout the year.

Marsupial sense and communicate with vision, touch, sound and chemicals usually detected by smelling. Marsupials are not very vocal. When they are, vocalizations are used in mating encounters, to express territoriality, for mother and young communication, and to express alarm and warn others when danger is sensed. It has been hypothesized that Australian marsupials have color vision because they have rods that perceive red, blue, and green like the rods of primates). Many species have conspicuous color patterns that may convey information about sex or species identity. Pheromones (chemicals released into air or water that are detected by and responded to by other animals of the same species) may also used in communication of reproductive receptivity. |=|

Marsupial Mating and Reproduction

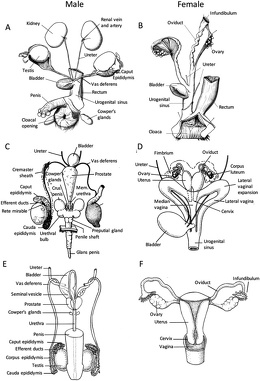

Comparative mammalian reproductive anatomy: A) Male prototheria – Echidna; B) female prototheria – Echidna; C) male metatheria – Tammar Wallaby; D) female metatheria – Tammar Wallaby; E) male eutheria – Human; F) female eutheria – Human, from Marsupial — an overview ScienceDirect Topics

Mating systems of marsupials vary considerably. They can be 1) monogamous (have one mate at a time); 2) polygynous (males have more than one female as a mate at one time); or 3) They are polygynandrous (promiscuous), with both males and females having multiple partners. Many species are solitary throughout the year, only coming together to mate — a pattern that is consistent with promiscuous mating systems . Males of some species defend their access to several females. Polygyny can take the form of male dominance hierarchies in highly social species such as whiptail wallabies, which can live in groups of up to 50 individuals. Monogamy is practiced by greater gliders, which live in small family groups that consist of a mated pair and their offspring. [Source: Matthew Wund and Phil Myers, Animal Diversity Web (ADW)|=|]

After ejaculating sperm some male marsupials produces a kind plug of which seals the female's orifice and prevents competitors from impregnating her. Some marsupials have bifurcated penises. One Australian zoo director experimenting with the breeding of endangered marsupials told Culture Shock: Maybe we have double the chance of success!’ [Source: Ilsa Sharp, “CultureShock! A Survival Guide to Customs and Etiquette: Australia”, Marshall Cavendish, 2009]

According to Animal Diversity Web: Marsupials and placental mammals differ strongly in their reproductive anatomy and pattern. In females, the reproductive tracts of marsupials are fully doubled. The right and left vaginae do not fuse to form a single body, as they do in all placental mammals, and birth takes place through a new median canal, the pseudovaginal canal. Right and left uteri also are unfused (varying degrees of fusion are found in placental mammals). Also, in the developing marsupial embryo, the arrangement of ducts that become the female reproductive tract is different in marsupials compared to placentals. In some (but by no means all) species of marsupials, females develop a pouch or marsupium in which the young are nursed. In males, the penis, like the female vagina, is bifid, or doubled. The scrotum lies in front of the penis instead of posterior to it, as in placental mammals.

It has been suggested that the marsupial pattern of reproduction is more primitive than for eutherian mammals. Lillegraven (1975) argued that marsupial young must be born quickly, before the mother's immune system can respond the presence of foreign tissue in the form of a developing embryo. Most development takes place in the pouch, safe from maternal immune attack. Eutherians "solved" the problem of immune rejection through the evolution of a complex set of interactions that take place in the trophoblast, a part of the developing egg of eutherians that is not found in marsupials. Whether this is likely to be true — and whether retaining a primitive style of reproduction suggests any kind of competitive inferiority — has been hotly debated.

Marsupial Offspring and Parenting

Marsupial young are altricial, meaning they are underdeveloped at birth. They may be so small that in many cases a dozen marsupial newborns can be placed in a teaspoon. The rearing of offspring is done exclusively by females who keep their young in their pouch. During the pre-weaning stage provisioning and protecting are done by females Pre-independence protection is provided by females. The post-independence period is characterized by the association of offspring with their parents. [Source: Matthew Wund and Phil Myers, Animal Diversity Web (ADW)|=|]

Matthew Wund and Phil Myers wrote in Animal Diversity Web: Perhaps the most conspicuous difference between marsupials and placental mammals is in the degree of development of the young at birth. Marsupial young are tiny at birth; litters always weigh less than one percent of the mother's body weight and individual young sometimes weigh only a few milligrams. They are born after a very short gestation period (8 to 43 days, depending on species; always less or equal to the length of an estrus cycle), and in what seems to our placental-biased point of view to be an extraordinarily underdeveloped state. A placenta is formed in only a few species and, even in those, the gestation period is extraordinarily short. At the time newborn marsupials emerge from their mother's reproductive tract and crawl to the pouch, they are tiny and have just begun forming functional organs. The forelimbs are fairly well developed, as they are required for the young pull to themselves along the mother's belly by grasping hairs with the forelimbs, but the hindlimbs are mere paddles. The heart, kidneys, and lungs are all barely functional. Even the brain is at an early ontogenetic stage. Most development takes place in the pouch and the lactation period is prolonged.

Much of development in marsupials occurs after birth while the young are nursing. In about 50 percent of marsupial species, young develop within the confines of a marsupium, or pouch. Weaning may take place after a year or more in some species (such as kangaroos and wallaroos). Thus, female marsupials invest very little energy and resources into gestation, but lactation requires a substantial investment. The pouch itself (or protective folds of skin in many species) may be permanent, or may only develop at the onset of reproduction. In either case, resources must be devoted to producing and maintaining the structures that will protect the developing young. |=|

Young generally do not associate directly with their mothers for much more than several weeks once they are fully independent of the pouch. This is generally true for both non-social and social species. In at least one species (Red-necked wallaby), extended associations between females and their independent young are known to reduce the success of future reproduction. |=|

Marsupials 'More Evolved' than Humans?

Marsupials have a radical evolutionary history that suggests they are "more evolved" than previously thought, a study published on April 28, 2024 in the journal Current Biology suggests. Patrick Pester wrote in Live Science: Marsupials used to be considered an evolutionary stepping stone between egg-laying mammals called monotremes, such as platypuses, and placental mammals, such as humans. While modern science now recognizes that marsupials and placentals evolved from a common ancestor around 160 million years ago, the authors of the study argue that marsupials retain a slight stigma from the days when they were classified as an intermediary. [Source:Patrick Pester, Live Science, May 2, 2023]

By scanning the skulls of placental mammals and marsupials in various stages of development, the researchers concluded that the developmental strategy of placental mammals — and not marsupials — is closer to that of their common ancestor, suggesting that if anything, marsupials have evolved more than placental mammals since the split. "They have a much more extreme evolutionary story compared to placentals, so the idea of them as being these half animals or half mammals is wrong," study co-author Anjali Goswami, a research leader of life sciences at the Natural History Museum in London, told Live Science. "In a sense, they're the more evolved or more divergent group."

Placental mammals have a range of developmental strategies. For example, human babies are practically helpless at birth, unable to walk, while zebra foals are mobile within hours, according to the book "Encyclopedia of Child Behavior and Development" (Springer, 2011). However, no placental newborns are as immature as marsupial offspring. Marsupials give birth to fetus-like embryos that climb from the birth canal to their mothers' pouches to complete development, according to the San Diego Zoo.

For the new study, researchers created 3D images of 165 mammal skulls, ranging from fetal to adult, across 22 species. Then, they placed points on the images that acted as 3D coordinates to capture the overall skull shape and determine how the skulls developed in each species. Finally, they compared this development between marsupials and placental mammals to what they estimated for their hypothetical common ancestor.

Placental skull development was more similar to that of the predicted ancestral mammal than was the marsupial skull development. That led the authors to hypothesize that the common ancestor developed like placentals, and that the extreme marsupial strategy of finishing gestation in a mother’s pouch came later. First author Heather White, a postdoctoral researcher at the Natural History Museum, told Live Science that marsupials underwent a deceleration in their rate of skull growth compared with placental mammals and the ancestral mammal; thus, it's the marsupial strategy that has changed more from the ancestor state. "It really does put marsupials in a new light, which is very exciting," White added.

Gregory Funston, a postdoctoral fellow of paleontology at the Royal Ontario Museum in Canada who was not involved in the study, told Live Science that the new research keys into a major misconception that, historically, shaped a lot of research, with marsupials thought of as less successful intermediates. "I'm really impressed by the study, and I hope that it will help to shift our thinking about marsupials as much as I think it will," Funston said. "Of course we've known they aren't intermediates for a long time, but White and colleagues' study convincingly argues that marsupials actually have a highly specialized developmental pattern."

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org , National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, David Attenborough books, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2025