Home | Category: Kangaroos, Wallabies and Their Relatives

KANGAROO HOPPING

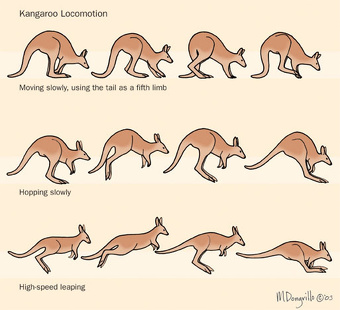

Hopping is the primary mode of locomotion for large marsupials such as kangaroos, wallabies, and rat-kangaroos. They are the only large animals known to hop. When moving rapidly, macropods use only their hind legs, keeping their tails extended behind them for balance. However, when moving slowly, they use all four feet and their tails in locomotion.

Kangaroos can cruise at speeds of 28 to 32 kilometers per hour (15 to 20 miles per hour) and can accelerate to twice that speed if necessary. Eastern grey kangaroos and red kangaroos have been clocked hopping at 64 kilometers per hour (40 miles per hour). A female red kangaroo once jumped 12.8 meters (42 feet). According to the Guinness Book of Records, there is an unconfirmed report of a eastern gray kangaroos leaping 13.6 meters (44½ feet). A gray kangaroos was observed jumping over a three-meter-high (ten-foot-high) pile of timber.

Many kangaroo species use less energy hopping at 28 to 32 kilometers per hour (15 to 20 miles per hour) mph than they do walking more slowly, when their heavy tails act like loads that have to be carried. When they hop the tail acts as a counterweight rather than a burden and they can move along at steady clip for miles, using less energy than other animals do when they run. Kangaroo tails serve as a counterbalance when hopping, a kind of chair when standing still and a fifth limb when moving slowly.

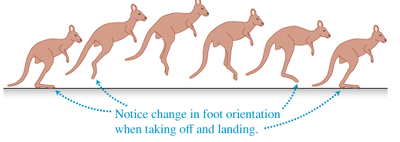

The hindquarters and legs make up to three quarters of a kangaroo's weight. There are four toes on each of the two find feet, with the one toe considerably larger than the others. Hopping kangaroos push off on their enlarged fourth toe, and to a lesser degree their fifth toe. The first toe has all but disappeared and their second and third toe are fussed together into a claw used primarily for grooming and scratching. The up and down motion of the tail of a hopping kangaroo acts as a counter-balance and the hopping motion itself helps pump air in and out of the kangaroos lungs.

Kangaroos are able to move so quickly by storing energy with each hop utilizing the principal of the spring. "Because of the elastic storage of energy in its tendons," says Domico, "the faster a 'roo' travels the more energy it saves...Kangaroos increase their speed by increasing their stride."

RELATED ARTICLES:

KANGAROOS AND WALLABIES (MACROPODS): CHARACTERISTICS, HISTORY, POPULATIONS ioa.factsanddetails.com

KANGAROO BEHAVIOR: FEEDING, REPRODUCTION, JOEYS ioa.factsanddetails.com

RED KANGAROOS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

GREY KANGAROOS: EASTERN, WESTERN, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

KANGAROOS AND PEOPLE: AUSTRALIANS, HISTORY, ART, SKIPPY ioa.factsanddetails.com

KANGAROOS IN MODERN AUSTRALIA: MEAT, LEATHER, CAR COLLISIONS AND ROO BARS ioa.factsanddetails.com

KANGAROO ISSUES: OVERPOPULATION, PESTS, CULLS, SHOOTERS, ANIMAL RIGHTS ioa.factsanddetails.com

KANGAROO ATTACKS: HUMANS, DOGS, HOW, WHY, WHERE ioa.factsanddetails.com

MARSUPIALS: HISTORY, EVOLUTION, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

MARSUPIALS IN AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

MARSUPIALS IN AUSTRALASIA (AUSTRALIA, NEW GUINEA, NEARBY ISLANDS) ioa.factsanddetails.com

WALLAROOS: SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

WALLABIES: TYPES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

TREE-KANGAROOS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

TREE-KANGAROOS IN AUSTRALIA: BENNETT'S, LUMHOLTZ'S, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

TREE-KANGAROOS IN PAPUA NEW GUINEA: SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

TREE-KANGAROOS IN WEST PAPUA, INDONESIA: SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

Macropod Hopping Anatomy and Dynamics

According to National Geographic: Graced with large, powerful hind legs and feet; a big, muscular tail; and a narrow, strongly fused pelvis, a kangaroo moves like a bouncing ball. The trick is in its elastic tendons, which store and recover the force of each hop, like a spring. [Source: Jeremy Berlin, National Geographic, February 2019]

Macopods have a plantigrade posture suited for walking on the soles of the feet, like a human or a bear. According to Animal Diversity Web: They have long, narrow hind feet and powerful hind limbs. The fourth toe of the hind foot is the longest and strongest. It lies in a line with the main limb elements and transmits the thrust of hopping (this toe is secondarily somewhat reduced in rock wallabies and tree kangaroos). The outside (fifth) toe is also large. As is true of all members of their order (and members of the order Peramelemorphia as well), macropods are syndactylous, that is, the second and third toes are fused for most of their length, but end in separate nails that are used for grooming. The big toe is greatly reduced or (usually) absent. The tail is long and heavy in most macropods, but it is not prehensile. Instead, it is used as a balancing or stabilizing organ. The tails of members of one group of macropods, the nail-tail wallabies (genus Onychogalea), have a horny tip. This tip is pressed into the substrate for purchase when the animal jumps. [Source: Phil Myers, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

To move fast, most members of this group use a bipedal form of hopping. The animal takes off with a push from its large and muscular hind limbs and lands on its hind feet and tail. At high speeds (up to 50 km/h!) the tail remains off the ground and is used for balance. At slow speed, macropods land on their forelimbs and tail, while swinging their hindlimbs forward. Curiously, they can't walk backwards. At low speeds, hopping locomotion is inefficient and expensive energetically. At high speeds, however, it is highly efficient. |=|

While a tail and hind feet specialized for hopping characterize most macropods, a few have shorter and broader hind feet and a shorter tail than the kangaroos and wallabies. These forms include the tree-kangaroos (genus Dendrolagus), which are excellent climbers; pademelons (genus Thylogale), which often walk with a quadrupedal gait; and the relatively short-tailed quokkas (genus Setonix). |=|

Studying Kangaroo Movement

Beginning in 1973, Professor Terry Dawson, then at Harvard University, used treadmills to study kangaroo movement. He told National Geographic: “One young lady hopped for half an hour. She’d come out of here pen and stand in the treadmill waiting for us to turn it on.” [Source: Luna Syr, National Geographic]

Observing red kangaroos Dawson and his team found that longer strides rather than more frequent ones produced increases in speed. Hopping strides ranged from around 75 centimeters to 5.2 meters (2.5 to 17 feet). Eighty percent of he the animal’s muscle mass is concentrated around the pelvis. These muscles are chock-a-block with capillaries and energy-producing mitocondria. Large tendons and calf muscles contract and release like springs.

According to National Geographic: At slow speeds, kangaroos use their forelegs and tail to hold themselves up while swinging their hind legs forward. For red kangaroos, walking changes to hopping at around six kilometers per four (four miles per hour). The top speeds reached were around 56 kilometers per hour (35 miles per hour). Dawson said: “It’s an incredibly graceful way of moving. They appear to be just gliding along.

Later Dawson moved Australia and became a professor at the University of New South Wales. During hopping, the kangaroo tail acts as a counterbalance, and as a spring to store up energy for the next bounce. "Hopping is an exaggerated gallop, enabling the kangaroo to make longer steps," says Dawson.

Hopping Requires More Energy Than Previously Thought

Genelle Weule of ABC wrote: Hopping does not help Australian marsupials save energy, instead the physical feat requires the aerobic capacity of a super-athlete, research shows. This view of marsupial metabolism may help explain how large animals such as kangaroos developed hopping, says Dawson "Large hoppers are so specialised we can't really see how they've got to where they are," says Dawson. But the discovery that marsupials can produce high levels of energy suggests hopping may have originated in small, active, arboreal forms such as possums, Dawson and Dr Koa Webster from Macquarie University told the 59th annual scientific meeting of the Australian Mammal Society. [Source: Genelle Weule, ABC, July 9, 2013]

It had been assumed that marsupials had low metabolisms and hopping conserved energy while travelling at high speeds that rival many placental mammmals such as horses. "It was thought they had low energy production overall and hopping was a way of getting around the limitations of not being athletic enough," says Dawson. But Dawson and Webster's research suggests the opposite is true.

To understand the energy demands of hopping, they studied the oxygen consumption, muscle anatomy and mitochondrial densities of kangaroos and much smaller marsupials such as bettongs and quadripedal marsupial mice. They found that hopping is energy intensive. "Although marsupials have a low resting metabolism, they have the capacity to expand it very markedly," says Dawson. "So kangaroos are actually super-athletes. Instead of having a spring to make them more efficient hopping is actually an extended gallop to allow them to go faster. They've got more muscle than just about any other mammal and they've got more mitochondria and blood vessels in their muscle," says Dawson. But kangaroos are not alone, even the smaller animals' aerobic capacity rival or surpass equivalent-sized placental mammals, they found. T

How Hopping Might Have Evolved

Genelle Weule of ABC wrote: The discovery that all marsupials appear to have this innate ability to ramp up their metabolic rate when needed led the researchers to speculate about how hopping may have evolved. "Possums are the closest relatives of the kangaroo. The notion was that they must have come from possum-type animals in trees, but we didn't know how they could [if they had a low metabolic rate]," says Dawson.

To investigate how this leap may have happened, Dawson and Webster looked at the evolution of bush babies or galagos — a type of African primate that is both a tree-dweller and ground hopper — as an analogy to the evolution of kangaroos. The size of a rat, these energetic primates can leap up to two to three metres. "They're very fast moving in trees, but some [species] have actually come down in more open woodland." Once on the ground, bush babies hop at high speed to evade predators. "We've seen how bush babies came down out of the trees in recent geological time have got this hopping going on, so it's not a long bow to pull now that we know that marsupials have the metabolic capacity for fast hopping."

Dawson and Webster found striking similarities when they compared the anatomy and muscle structure of bush babies to small marsupials. "The small leaping bush babies have got almost identical limb structure and function and long tail that you get in small hopping kangaroos — the wallabies, small potoroos and bettongs," says Dawson. "So we have a template for how the marsupials might do it, or the possum might have developed it."

Kangaroos Use Their Tails When They Walk

Kangaroos use their tail as an extra leg and use their tail more than their forelimbs when they walk according to a study published in the Royal Society Biology Letters in 2014. Stuart Gary of ABC wrote: When kangaroos walk they had been observed to use what is known as a "pentapedal tail walk", says Dawson. This unusual gait means the animal effectively always has three points on the ground, with one of them always being their tail, and the other two being either their two hind legs, or their two forelimbs. However the energetics of pentapedal walking indicated that it was less energy efficient than walking on four legs, says Dawson. "This was always a puzzle," he says. [Source: Stuart Gary, ABC, July 2. 2014]

While previous literature suggested kangaroos used their tail as a "strut to hold the body in place while they move the back legs forward," Dawson suspected something else was happening. "It appeared to me they were using the tail for propulsion when walking," he says. To test this hypothesis, Dawson and colleagues trained one male and four female red kangaroos (Macropus rufus) to walk over a force-measuring platform that monitored the energy used by different parts of the kangaroo as it walked.

The researchers found that kangaroos walk by using the tail to lift both hind legs and the body's centre of gravity forward, while the forelimbs were used as struts and didn't provide any of the propulsion. The tests showed there was far more propulsion energy provided by the tail than scientists had thought. The kangaroo's tail provides as much propulsive energy as one of the hind legs, between a quarter and a third of the full propulsion needed to move the animal forward, they found. "We expected this is because the muscles in the tail and hind legs are highly aerobic, with a lot of mitochondria in them doing a lot of work," says Dawson.

Mitochondria act as a cell's power house, providing energy. "The muscle structure of the front legs have little mitochondria and they're not organised for propulsion, so instead of the tail being the strut, the front legs were filling that role," says Dawson. "I can now understand where that energy goes and why if they're going to walk more than five meters they get up and hop instead."

Dawson says the team is interested in mechanical analogues to walking and locomotion. "There's interest in the robotic side of things and how other forms of locomotion can work," says Dawson. "You can locomote just using your legs, but there are other options for stability and it's interesting from that point of view."

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org , National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, David Attenborough books, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2025