PROTEMNODONS — GIANT KANGAROOS

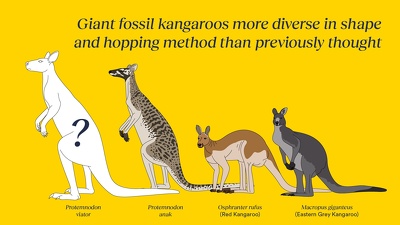

Protemnodon was a giant, now-extinct kangaroo that lived in Australia, Tasmania, and New Guinea in the Pliocene and Pleistocene Period (5.4 million to 11,700 years ago). Recent analysis of mtDNA extracted from fossils indicates that Protemnodon was closely related to Macropus (the kangaroo genus). A 2024 review of the genus recognized seven species: 1) P. anak (1874 the type species); 2) P. otibandus (1967); 3) P. snewini (1978); 4) P. tumbuna (1983); 5) P. mamkurra (2024); 6) P. viator (2024); 7) P. dawsonae (2024) Several species of Protemnodon survived up until around 50,000 years ago. P. tumbuna may have survived in the highlands of Papua New Guinea as recently as 12,000 years ago [Source: Wikipedia]

Based on fossil evidence, Protemnodon is thought to have been physically similar to wallabies, but generally larger and more robust. Protemnodon roechus was the largest in the genus, weighing around 170 kilograms (375 pounds). There have been reports in the popular media of towering ones that weighed 300 kilograms and were up 2.5 meters, ven three neters. One source said they were so big that scientists were studying whether they could hop.

Some studies show that Protemnodon species ranged from efficient hoppers of dry open habitats (such as P. viator) to slower, more quadrupedal forest dwellers (like P. tumbuna), while others have found that even species such as P. viator were very inefficient hoppers and primarily quadrupedal. The shape and articulation of the forelimbs suggests that they may have been adept at digging, while the claws on their hind feet had a curved shape, perhaps to help stabilise the animal on uneven ground.

See Separate Articles: ICE-AGE ANIMALS IN AUSTRALIA: WHEN, WHERE AND HOW THEY LIVED AND WENT EXTINCT ioa.factsanddetails.com ; GIANT ICE-AGE ANIMALS IN AUSTRALIA: DINOSAURS IN AUSTRALIA: TYPES, CHARACTERISTICS, WHEN AND WHERE ioa.factsanddetails.com

Diet of Procoptodon Goliah — Evidence It was Hunted to Extinction?

Procoptodon goliah was a giant 230-kilogram kangaroo that lived up until around the time humans arrived in Australia. Palaeontologist Dr Gavin Prideaux of Flinders University in Adelaide and colleagues found carbon isotopes and microscopic scratches in the teeth of Procoptodon goliah — the 230-kilogram kangaroo — which suggests it ate tough drought-tolerant plants. Anna Salleh of ABC wrote: Given the kangaroo's bones are distributed in dry regions where the hardy, drought-tolerant saltbush grows they conclude this was its main food. An analysis of oxygen isotopes in the kangaraoo's teeth back up the conclusion, suggesting it had to drink a lot from water holes to counteract the salt from plants it ate.[Source: June 23, 2009]

Prideaux says this and other evidence suggests the kangaroo was adapted to dry conditions, and says this undermines the idea that climate change was the reason the animal went extinct. He says saltbush does not burn well, which undermines another theory, that human burning of the landscape was the cause of extinction. Prideaux says this all points to hunting as the only viable theory to explain the animal's extinction.

But archaeologist Dr Judith Field of the University of Sydney rejects this conclusion as "completely unsubstantiated" and a "giant leap of faith". She says the research provides "terrific" information on the diet and distribution of the P. goliah. But just because the kangaroo was adapted to aridity doesn't mean it was hunted to extinction and was not vulnerable to extreme aridity, says Field. Her main concern is that there is no direct evidence showing the kangaroo was hunted by humans. "If you're going to make any case about humans and these megafauna then you've got to have them in the same place in the same time," she says. "You've got to find archaeological sites that have megafauna in them with evidence of butchering. And we just don't have these."

Thylacoleo — Marsupial Lion

Thylacoleo ("pouch lion") were an extinct genus of carnivorous marsupials commonly referred to as marsupial lions. They lived in Australia from the late Pliocene to the Late Pleistocene Periods (3.6 million until around 40,000 years ago). They were the largest and main apex predator within Ice-Age Australian ecosystems. The largest and last species, Thylacoleo carnifex, approached the weight of a lion. Their average weight has been estimated to ranges from 101 to 130 kilograms (223 to 287 pounds). Individuals stood around 75 centimeters (30 inches) at the shoulder and were about 150 centimeters (59 inches) from head to tail. [Source: Wikipedia]

The ancestors of marsupial lions are believed to have been herbivores, something unusual for carnivores. They are members of the Vombatiformes, an almost entirely herbivorous order of marsupials, of which koalas and wombats are the only extant representatives. This clasiification is based largely on the teeth of marsupial lions, which are laid out those of koalas and wombats. Desoite this, pound for pound, T. carnifex had the strongest bite of any mammal species, living or extinct. A T. carnifex weighing 101 kilograms (223 pounds) had a bite comparable to that of a 250 kilograms African lion, and research suggests that Thylacoleo could hunt and take prey much larger than itself.[20] Larger animals that were likely prey include Diprotodons (giant wombats) and giant kangaroos.

Using 3D modeling based on X-ray computed tomography scans, scientists found marsupial lions were unable to use the prolonged, suffocating bite typical of living big cats. They instead had an extremely efficient and unique bite; the incisors would have been used to stab at and pierce the flesh of their prey while the more specialised carnassials crushed the windpipe, severed the spinal cord, and lacerated the major blood vessels such as the carotid artery and jugular vein. Compared to an African lion which may take 15 minutes to kill a large catch, the marsupial lion could perhpas kill a large animal quicker, maybe in less than a minute. The skull was so specialized for big game that it was very inefficient at catching smaller animals, which possibly contributed to its extinction.

Thylacoleo had highly mobile and powerful forelimbs used to grapple prey, with each foot having a single very large retractable hooked claw set on large semi-opposable thumbs, which are suggested to have been used deal a killing blow. The hind feet had four functional toes, the first digit being much reduced in size, but possessing a roughened pad similar to that of possums, which may have assisted with climbing. Its strong forelimbs and retracting claws mean that Thylacoleo possibly climbed trees and perhaps carried carcasses to keep the kill for itself (like leopards do today). The climbing ability would have also helped them climb out of caves, which could therefore have been used as dens to rear their young. Specialised tail bones called chevrons strengthened the tail, likely allowing the animal to use it to prop itself up while rearing on its hind legs, which may have been done when climbing or attacking prey.

Nimbadons — Large, 15-Million-Year-Old, Tree-Dwelling Marsupials

Nimbadons were sheep-sized relatives of modern-day wombats that lived in Australia’s treetops 15 million years ago and were strikingly similar to koalas. According Dr Karen Black from the University of New South Wales said they were the largest arboreal marsupial herbivores ever known. As of 2012 more than 30 Nimbadon skulls and numerous skeletons had been recovered from the fossil cave, known as AL90, at Riversleigh, in north-western Queensland.. Discovering such a large cluster suggests the animals may have traveled in mobs — or herds — like modern-day kangaroos, Black told Associate Press. The Nimbadon skulls included those of babies still in their mothers' pouches, allowing the researchers to study how the animals developed. The skulls revealed that bones at the front of the face developed quite quickly, which would have allowed the baby to suckle from its mother at an extremely young age. Those findings suggest the Nimbadon babies developed very similarly to how kangaroos develop today — likely being born after a month's gestation and crawling into their mother's pouch for the rest of development, Black said. [Source: Associated Press, July 16, 2010]

Black wrote in SBS News: Studies of the exquisitely preserved skulls and teeth has revealed that Nimbadon was a browser of soft vegetation, had relatively forward-facing eyes and an unusual short, bulbous snout. Like the koala, Nimbadon had powerful forelimbs with highly mobile shoulder, elbow and wrist joints. These would have allowed significant extension and rotation of the arms, movement that is essential for manoeuvring through a tree canopy, reaching for new supports and for balancing on branches. Nimbadon's hands and feet were extremely large and equipped with long, flexible fingers and toes, semi-opposable first digits and massive, sharp, re-curved claws. Combined with the deep carpal tunnel of the wrist (to house the flexor tendons of the fingers), these features suggest Nimbadon possessed an exceptionally powerful grasp with claws capable of deeply penetrating the tree trunk during climbing. [Source: Karen Black, University of New South Wales, SBS News, November 24, 2012]

Like the koala, Nimbadon may have adopted a trunk-hugging climbing style. Interestingly, Nimbadon may also have been hanging from tree branches. Nimbadon is unique among marsupials in having short hindlimbs relative to its forelimbs. These limb proportions are found today in animals such as sloths and some apes that regularly hang from tree branches using their powerful forelimbs.

While a 70 kilograms tree-dwelling marsupial may seem improbable, large arboreal and/or climbing mammals are well known, especially in rainforest habitats like that of Nimbadon's. For example, the orangutan, the largest living arboreal mammal, can reach weights in excess of 100 kilograms. Bears are also habitual climbers. The Malayan Sun Bear spends a significant amount of time feeding within the canopies of the lowland tropical rainforests of South East Asia, and has even been known to build nests in the trees. Nimbadon's climbing ability would have given it access to multiple layers of the rainforest canopy for both food and protection from predators. It may also have played a role as a large seed disperser in Australia's ancient forests, supplementing its diet with fruit. Perhaps the bulbous snout and enlarged nasal sinuses are evidence for an enhanced olfactory system to detect these fruits.

So how did an ancient cave become a graveyard for so many tree-dwelling individuals of Nimbadon? The geology of AL90 suggests that the ancient cave's entrance was vertically orientated, with its opening at ground-level. Obscured by vegetation, the entrance would have acted as a kind of pit-fall trap with unsuspecting animals dropping in. While moving through the tree crowns that would have arched over the cave's entrance, every once in a while individuals would have missed their grip and dropped into what was to become the AL90 time capsule. The large number of Nimbadon within the fossil cave suggests they may have been common within their rainforest environment and may have moved through the tree tops in herds or large family groups. Nimbadon disappeared from the fossil record around 15 million years ago, at a time that coincided with the beginning of Australia's transformation from lush greenhouse environments to the dryer, cooler, climatically unpredictable continent we see today. The primary inland rainforest habitat of Nimbadon gradually gave way to open forests and with this change, Nimbadon's time came to an end.

Diprotodons — Rhinoceros-Sized Mega-Wombats

During the Pleistocene Period (2.6 million to 11,700 years ago), herds of giant wombats the size of a rhinoceros roamed the plains of southern Australia. These mega-wombats were called Diprotodons. Diprotodons were the largest marsupials ever to roam the earth, weighing up to 2.8 tonnes and living between two million and 50,000 years ago and dying out around the time indigenous tribes first appeared. A relative of the modern-day wombat, these herbivores were just one of many of megafauna to roam ancient Australia. Megafauna are thought to have evolved to such large sizes to cope with inhospitable climates and food scarcity,

In 2012, Australian scientists said they had found the biggest-ever graveyard of diprotodons in remote fossil deposit in the Queensland outback. The site contains up to 50 diprotodon skeletons including a huge specimen named Kenny, whose jawbone alone is 70 centimeters (28 inches) long. Lead scientist on the dig, Scott Hocknull from the Queensland Museum in Brisbane, said Kenny was one of the largest diprotodons he had ever seen and one of the best preserved specimens. "When we did the initial survey I was just completely blown away by the concentrations of these fragments," he told AFP by telephone from the far-flung desert dig site, which he estimated at between 100,000-200,000 years old. [Source: Amy Coopes, AFP, June 21, 2012]

Hocknull likened diprotodon to "a cross between a wombat and a bear but the size of a rhinoceros". They were Pigeon-toed and with a backward-facing pouch large enough to carry an adult human, The mega-wombats in the mass graveyard appeared to have been trapped in boggy conditions at the site after seeking refuge there from extremely dry conditions during a period of significant climate change in ancient Australia,

Towering super-kangaroos up to 2.5 meters tall called protemnodon have also been discovered at the location, along with the remains of tiny frogs, rodents and fish — an important find in what is now an extremely arid region. "Very little is known about arid zone fish and their evolution, and finding a fossil record for them is amazing," said Hocknull. A huge array of other animal bones have also been found at the site, including the teeth of a six-meter long venomous lizard called megalania and the teeth and bony back-plates of an enormous ancient crocodile. "We're almost certain that most of these carcasses of diprotodon have been torn apart by both the crocodiles and the lizards, because we've found shed teeth within their skeletons from both animals," Hocknull said.

In 2023, scientists announced that they had found the skeletons of several of the world's largest marsupials ever at a "unique" fossil site in Western Australia. The remains were of Diprotodons, giant marsupials related to wombats and koalas and lived during the Pleistocene epoch (about 2.6 million to 11,700 years ago). These megafauna stood up to 1.7 meters (5.6 feet) tall at the shoulder, were 3.8 meters (12.5 feet) long and weighed up to 2.8 metric tons (3.1 tons). Researchers found the skeletons of at least 10 Diprotodon adults and juveniles may be among the fossils, at the site. which could mean the site was on a major migration route for Diprotodon, the team said in a statement released by the Western Australian Museum on October 19. [Source: Patrick Pester, Live Science, October 25, 2023]

Patrick Pester wrote in Live Science: There are parts of the ancient marsupials' skulls, bones and teeth lying all over the ground, Gilbert Price, a paleontologist at the University of Queensland who is part of the excavation, said. "I've never seen a fossil site quite like this," Price said. "It's not normal to be able to walk across the landscape and just look on the ground and say, 'That's a vertebra, there's another part of a leg bone, there's a skull over there…' This is the sort of stuff that you might see in a movie like Jurassic Park."

3.1-Ton Diprotodons — Largest Marsupials Ever

Diprotodon emerged around two million years ago and went extinct about 25,000 years ago. Climate change and human activity may have been factors in their extinction, but they co-existed with Aboriginal people for more than 20,000 years, according to the Australian Museum in Sydney. Researchers have found Diprotodon fossils all across Australia. They were first unearthed at the site of the new excavation, located in Du Boulay Creek, in 1991. The new discoveries establish the creek as a site of major scientific significance, according to another statement.

The researchers also found evidence of ancient mangroves and crab fossils among the megafauna. Price said the fossil deposit combines land animals like Diprotodon with "estuarine or almost marine types of conditions." "It's something that's absolutely unique in the fossil record, not only to this part of Western Australia, but the entire continent itself," he added.

Ambulator — 250-Kilogram, 3.5-Million-Year-Old Migrating Marsupial

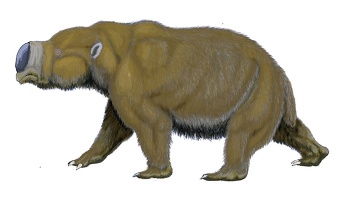

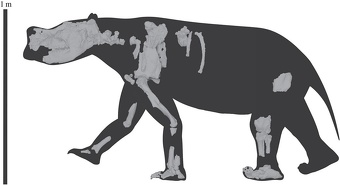

In 2023, scientists described a new species — Ambulator keanei — that weighed around 250 kilograms (550 pounds), was around on meter (3.3 feet) tall at the shoulder and had a body plan similar to a bear or rhinoceros. A. keanei once migrated long distances across Australia and belonged to the family Diprotodontidae, which once included giant wombat-like marsupials. The largest species in this group, Diprotodon optatum, was larger than car and weighed up to three tons (2.7 metric tons). [Source: Harry Baker, Live Science, June 2, 2023]

Harry Baker wrote in Live Science: , Scientists unearthed the partial skeleton of A. keanei in 2017 from an eroding cliff face at the Kalamurina Wildlife Sanctuary in South Australia. The bones date to around 3.5 million years ago during the Pliocene epoch (5.3 million to 2.6 million years ago). In a study, published May 31, 2023 in the journal Royal Society Open Science, researchers used 3D computer scans of the bones to create a model of what A. keanei may have looked like. The model suggests that the marsupial may have walked differently to similar-size animals that are alive today, which may have helped it to survive in a rapidly changing ecosystem.

"Most large herbivores today such as elephants and rhinoceroses are digitigrade (walking on their toes and not touching the ground with their heels, like a dog, cat, or rodent) , meaning they walk on the tips of their toes with their heel not touching the ground," study lead author Jacob van Zoelen, a doctoral candidate at Flinders University in Australia, said in a statement. "Diprotodontids are what we call plantigrade (walking on the soles of the feet, like a human or a bear), meaning their heel-bone [calcaneus] contacts the ground when they walk, similar to what humans do."

As a result, A. keanei would have conserved energy by evenly distributing its weight when walking, but its gait would have made running more difficult, he added. Its efficient strides may have enabled the newly described species to walk extremely long distances — a huge benefit because, at the time, Australia's lush woodland and grassland areas were transitioning to hot and arid deserts, forcing herbivores (eat plants or plants parts) animals like A. keanei to travel farther between food and water sources, study researchers wrote in an article for The Conversation.

The secret to A. keanei's efficient walking was a joint in its forearm wrists that gave it a "heeled hand," van Zoelen said. The joint meant that "the digits [on the hand] became essentially functionless and likely did not make contact with the ground while walking." This could help explain a longstanding marsupial mystery: Scientists have found fossilized footprints belonging to D. optatum, the largest ever marsupial, but the fossils don't have any toeprints. The new finding suggests this is because those toes never touched the ground.

A. keanei’s discovery may also help explain how D. opatum grew so big. The newfound marsupial’s even weight distribution may also have occurred in D. opatum and could have been a key factor in how D. opatum grew so large, the new research hints. The new find is important because until now, most knowledge about Diprotodontids came from jaw and teeth fossils, which has left big knowledge gaps about the family. They are very distantly related to other marsupials, which means it is hard to infer anything about them from living species. "There is nothing quite like them today," van Zoelen said. But findings like this will help improve our understanding of these extinct beasts, he added.

Genyornis — Australian Thunder Bird

Genyorni were ostrich-size flightless birds sometimes called Australia’s thunder bird. Members of the family Dromornithidae, which are related to modern waterfowl such as ducks, swans and geese, they stood more than two meters (seven feet) tall and weighed up to 240 kilograms (530 pounds) In 2022, Archaeology magazine reported: Charred eggshell fragments from numerous sites across Australia suggest that, 50,000 years ago, the continent’s earliest human inhabitants frequently dined on genyorni eggs. Analysis of samples from the site of Wood Point indicates that people raided the birds’ nests for their protein-rich eggs, each of which weighed more than three pounds. This likely contributed to the bird’s extinction. [Source: Archaeology Magazine, September 2022]

Genyornis newtoni was the largest genyorni species. Between 2013 and 2019, a team of paleontologists found numerous a G. newtoni fossils in southern Australia’s Lake Callabonna, including skull fragments, a skeleton and an articulated skull scientists reported in June 2024 in the journal Historical Biology. Mindy Weisberger of CNN wrote: Compared with the skulls of most other birds, G. newtoni’s skull is quite short. But the jaws are massive, supported by powerful muscles. “They would have had a very wide gape,” said lead study author Phoebe McInerney, a vertebrate paleontologist and researcher at Flinders University in South Australia. One previously unknown detail was a wide triangular bony shield called a casque on the upper bill, which may have been used for sexual displays, the study authors reported. [Source: Mindy Weisberger, CNN, June 4, 2024]

“The skull also hinted at G. newtoni’s diet. A flat gripping zone in the beak was suited for ripping up soft fruits and tender shoots and leaves, and a flattened palate on the underside of the upper bill may have been used for crushing fruits to a pulp. “We knew from other evidence that they likely ate soft food, and the new beak supported that,” McInerney said. “The skull also showed some evidence of adaptations for feeding in water, maybe on freshwater plants.”

This suggestion of underwater feeding is unexpected, given G. newtoni’s massive size, said Larry Witmer, a professor of anatomy and paleontology at Ohio University who was not involved in the research. “Maybe that shouldn’t be too surprising given that dromornithids like Genyornis are related to the group including ducks and geese, but Genyornis was six or seven feet tall and weighed maybe as much as 500 pounds,” Witmer said. Additional fossil discoveries could help resolve whether such adaptations were unused features inherited from aquatic ancestors, “or whether these giant birds were wading into the shallows in search of soft plants and leaves.”

“It surprised me how superficially goosey it looked, with its large spatulate bill, but definitely unlike any goose we have today,” Blokland said. “It has some aspects reminiscent of parrots, which it is not closely related to, but also landfowl, which are much closer relatives. In some ways it appears like a strange amalgamation of very different looking birds.”

For the new reconstruction, Blokland began with the bony external ear region, “as there were several specimens that preserved this part,” he said. From there, he constructed a scaffold that was consistent across multiple skull fossils. Some areas of the reconstruction were based on skulls belonging to other dromornithids or to modern waterfowl, and anatomical studies of modern birds hinted at how muscles and ligaments might move the bones.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org , National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, David Attenborough books, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2025