Home | Category: Kangaroos, Wallabies and Their Relatives

TREE-KANGAROOS IN AUSTRALIA

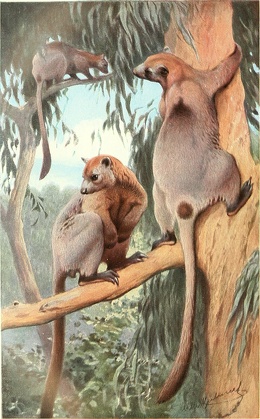

Two species of tree-kangaroos are found in Australia, Bennett's tree-kangaroo (Dendrolagus bennetianus) and Lumholtz's tree-kangaroo (Dendrolagus lumholtzi). Bennet's tree-kangaroos and Lumholtz's tree-kangaroo are found in the rainforests of northern Queensland. Both of these marsupials about the size of a cat. Their numbers have declined dramatically due to logging and loss of habitat due to agriculture.

Lumholtz's tree-kangaroos live on the southeast part of Cape York, near the coast in northern Queensland. Bennett's tree-kangaroos live about 150 kilometers north of Lumholtz's tree-kangaroo on the eastern part of Cape York, north of the Daintree River, near the coast in northern Queensland

Tree-kangaroos are marsupials of the genus Dendrolagus, adapted for living and getting around in trees. They inhabit tropical rainforests of New Guinea and far northeastern Queensland, Australia along with some of the islands in the region. All tree-kangaroos are considered threatened due to hunting and habitat destruction. They are the only true arboreal macropods (kangaroos and wallabies).

Most tree-kangaroos live in New Guinea. For a long time, Australia and New Guinea were joined, along with Tasmania, as part of a larger landmass called Sahul. This was the case during the last glacial period, when sea levels were lower. As the Earth warmed and glaciers melted, sea levels rose, flooding the low-lying areas and separating New Guinea and Tasmania from mainland Australia. The flooding of the Torres Strait, which separates New Guinea from Australia, is estimated to have occurred between 8,000 and 6,500 years ago, marking the final separation of Australia and New Guinea,

RELATED ARTICLES:

TREE-KANGAROOS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

TREE-KANGAROOS IN PAPUA NEW GUINEA: SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

TREE-KANGAROOS IN WEST PAPUA, INDONESIA: SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

MARSUPIALS: HISTORY, EVOLUTION, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

MARSUPIALS IN AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

MARSUPIALS IN AUSTRALASIA (AUSTRALIA, NEW GUINEA, NEARBY ISLANDS) ioa.factsanddetails.com

KANGAROOS AND WALLABIES (MACROPODS): CHARACTERISTICS, HISTORY, POPULATIONS ioa.factsanddetails.com

KANGAROO BEHAVIOR: FEEDING, REPRODUCTION, JOEYS ioa.factsanddetails.com

WALLABIES: TYPES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

WALLABY SPECIES ioa.factsanddetails.com

Bennett's Tree-Kangaroos

Bennett's tree-kangaroos(Dendrolagus bennettianus) are large tree-kangaroos and share the honor with koalas as being the biggest tree-dwelling mammals in Australia. The largest males of both species weigh almost 14 kilograms (31 pounds). Bennett's tree-kangaroos are very agile and are able to leap nine meter (30 feet) from an upper branch down to a lower branch and have been known to drop as 18 meters (59 feet) from branches in a tree to the ground without injury.

Bennett's Tree-kangaroo is named in honor of Dr. George Bennett, a zoologist and curator of the Australian Museum in Sydney, according to the Rootourism website. The species was formally described by De Vis in 1887.

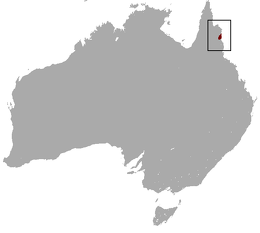

Bennett's tree-kangaroos are endemic to tropical rainforests in northeastern Queensland, Australia in relatively limited area, extending from the Daintree River in the south to Mt. Amos in the north and Mt. Windsor in the west. Within this range, which covers less than 4000 square-kilometers (1,544 square miles), these tree-kangaroos inhabit highland rainforest down to lowland riparian forests They are usually found in the canopy, but do come down to the forest floor to feed leaves and fruit that have fallen to the ground. [Source: Hien Nguyen, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List Bennett's tree-kangaroos are listed as Near Threatened. In CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild) they are in Appendix II, which lists species not necessarily threatened with extinction now but that may become so unless trade is closely controlled. Bennett’s tree-kangaroos mainly lived in protected areas with in the the Wet Tropics World Heritage Area, but may be still hunted by aboriginal groups. They are rare and elusive and usually don’t come in contact much with humans. In the past hunting pressure drove them into the mountains, where taboos and terrain prevented further pursuit by humans but with the decline of hunting some have returned to lower elevations. Their main predators, other than humans, are dingoes and Amethystine pythons.

Bennett's Tree-Kangaroo Characteristics and Diet

As we said before Bennett’s tree-kangaroo are among the largest arboreal (tree-dwelling) animals in Australia, with their average weight being 10.5 kilograms (23.1 pounds).. Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present. Males weigh from 11.5 to almost 14 kilograms (25 to 31 pounds). lbs), while the females range between about 8 to 10.6 kilograms (18 to 23 pounds). Their non-prehensile tail (73-80 centimeters females, 82-84 centimeters males) is longer than their head and body length (69-70.5 centimeters for females, 72-75 centimeters for males). [Source: Hien Nguyen, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]|

Bennett’s tree-kangaroos have mostly dark brown fur. The chin, throat, and belly are lighter in color. The feet are black; the forehead is greyish, the snout, shoulders, neck, and back of the head are a rusty tint. The tail has black patch at the base and light area on the top.

Bennett’s tree-kangaroos are herbivores (animals that primarily eat plants or plants parts) and primarily folivores (eat leaves). They particularly favor trees such as Ganophyllum, Aidia, and Schefflera and also eat a fair amount of the the vine Pisonia, and the fern Platycerium. Fruit is also consumed when available both in trees and on the ground. Preferred food trees are defended within territories and visited regularly. |=|

Bennett's Tree-Kangaroo Behavior

Bennett’s tree-kangaroos are very wary and shy, motile (move around as opposed to being stationary) and predominantly nocturnal (active at night), foraging and navigating their territories mainly at night. They are adapted for an arboreal (tree-dwelling) lifestyle, and are quite agile and mobile in the canopy, using their tails as a counterbalance when moving along branches. Once on the ground, they are able to move around well enough, hopping with their body leaning forward and the tail arched upward. [Source: Hien Nguyen, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Bennett’s tree-kangaroos are one of the few distinctly territorial macropods. Adult males maintain territories up to 25 hectares (61 acres), overlapping the territories of several females, which also maintain discrete territories. Populations of up to 0.3 Bennett’s tree-kangaroos per hectare can be supported in preferable habitats. Virtually all adult males carry scars from numerous intense, territorial conflicts, some even missing ears. Though solitary, adult males often come near females while navigating their territories, especially near food trees. The territories of adult females do not overlap. Individual females are solitary except when accompanied by one or two young or interacting with an adult male. |=|

Territories are usually centered around large trees used to rest in during the day. These resting areas, or roosts, are left at night and the tree-kangaroos forage amongst preferred feed trees, which are often found toward the edge of closed forest areas. During the day, Bennett’s tree-kangaroos are well camouflaged and difficult to see, sitting high in the canopy, often hidden by vines and branches. They sometimes sun themselves at the top of the canopy, sitting on vines, which hides views of them from from below.

Mating appears to be polygynous, since with the territories of several females are within the territory of a single male. |=|

Lumholtz's Tree-Kangaroos

Lumholtz's tree-kangaroos (Dendrolagus lumholtzi) are the smallest tree-kangaroos and the ones parhaps most closely linked in evolutionary terms to terrestrial kangaroos and wallabies. A 1985 study concluded that many of their behaviors — such as exclusively using bipedal hopping on the ground, moving paired limbs together when feeding, and being reluctant to climb downwards headfirst — made them less like tree-dwelling tree-kangaroos and more like their terrestrial ancestors. [Source: David Kellner, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

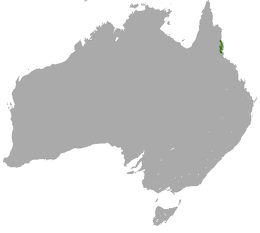

Lumholtz’s tree-kangaroos inhabit an area of approximately 5,500 square kilometers (2,123 square miles) in Northeast Queensland, Australia. Their range extends from the Daintree River in the north to the southern end of Cardwell Range in the south, where rainforest and wet sclerophyll forest interface in the west and the coast in the east. Their greatest concentrations are in the fragmented forests of the Atherton tablelands.

Lumholtz’s tree-kangaroos are often found in remnant and secondary rainforests on basalt soils mainly at elevations of 600 to 1200 meters (1968.5 to 3937 feet). They prefer upland rainforest and occurs at very low densities in lowland forests. Densities are twice as high on basaltic soil than on acid igneous or metamorphic rock substrate soils possibly due to basalt soil’s higher nutrient content) and have been observed in secondary and remnant forest fragments as small as 20 hectares (50 acres). Preferred habitats include microphyll vine forest, notophyll vine forest, sclerophyll communities, and cleared land. Lumholtz’s tree-kangaroos is often found in edge forest communities. It is unclear if this is because they spend a lot of time or because that is where they are most easily spotted by humans.

Lumholtz’s tree-kangaroos are not endangered or threatened. They are designated as a species of least concern on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List and have no special status on the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). They have been hunted by indigenous Australian populations for thousands of years but this practice is believed to have mostly stopped. The species has the potential to be an ecotourism draw. Habitat loss is a threat. Only around 12 percent of their range is in protected lands. They have a low birthrate and preference for small patches of isolated forest, they are vulnerable to being chopped down. Among the known predators are feral dogs, dingoes, humans and amethystine pythons. It is possible that juveniles are hunted by wedge-tailed eagles. The main anti-predator adaptation of Lumholtz’s tree-kangaroos are camouflage coloring and ability to seek refuge in hard to get places in the rainforest canopy.

Lumholtz's Tree-Kangaroo Characteristics and Diet

Lumholtz's tree-kangaroos are among are the smallest macropods (kangaroos and wallabies). They have a body and head length of 48 to 65 centimeters (19 to 26 inches), and a 60–74-centimeter (24–29 inch) -long tails. Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present: Males are larger than females. Males on average weigh 7.2 kilograms (16 pounds) and females weigh 5.9 kilograms (13 pounds). [Source: David Kellner, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

The hindlimbs of Lumholtz's tree-kangaroos are well developed but proportionally smaller than those of terrestrial kangaroos. Their tail and muscular forelimbs are proportionally larger than those of terrestrial kangaroos. The tail is hairy, uniformly thick and may be up to 15 percent longer than their head and body length. Their ears are short. Long, curved claws are present on all five digits of the forepaws. The hind paws include a large fourth digit and medium fifth digit; the first and second digits are fused together, but with two claws. No big toe is present. Both the fore and hind paws have large, fleshy pads with numerous tuberculations (papillae), used for gripping tree surfaces.

The entire body of Lumholtz's tree-kangaroos is covered in hair: back hair is grizzled gray with blackish tips and the underbelly is creamy or sometimes orange. The muzzle is black and there is a distinctive pale gray forehead band. The forepaws, hindpaws, and tip of the tail are also black. The adult tail is bicolored: the lower surface is black, and the upper surface is gray (same color as the back). Juveniles have an all-black tail and lack the pale forehead band.

Lumholtz’s tree-kangaroos are generalist herbivores (eat plants or plants parts) and are primarily folivores (eat leaves). They feed on the leaves of at least 37 species of plants, including trees, vines, shrubs, and epiphytes — mostly consuming adult leaves, but sometimes eating eating young leaves or flowers. Among the species commonly eaten are Cryptocarya triplinervis of the Lauraceae family, Alstonia scholaris of the Apocynaceae family, and Ripogonum album of the Vitaceae family. Lumholtz’s tree-kangaroos have been observed feeding several species of plant that are toxic to most mammals, including weedy Lantana camara, shining stinging trees (Dendrocnide photinophylla), and wild tobacco plants (Solanum mauritianum). Lumholtz’s tree-kangaroos have never been observed drinking water and there are few or no water bodies within the home ranges of most individuals. It is therefore assumed they get the water they need from the plants they eat. When feeding, Lumholtz’s tree-kangaroos move their forelimbs simultaneously to grab leaves, bring them closer to the mouth, and then chew. Digestion includes foregut fermentation.

Lumholtz's Tree-Kangaroo Behavior

Lumholtz’s tree-kangaroos are arboreal (live mainly in trees), scansorial (good at climbing), nocturnal (active at night), but do feed and move occasionally during the day, motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), sedentary (remain in the same area) and solitary (their mean group size of 1.07 adults or subadults). Males have home ranges of approximately four hectares (eight acres), which tend to overlap significantly with home ranges of other males and females. Females have home ranges of approximately two hectares (five acres), which do not overlap those of other females. [Source: David Kellner, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Lumholtz’s tree-kangaroo individuals tend ignore each other, even when in the same tree and do not appear to defend territories. Adults spend over 99 percent of their time in trees and are inactive (either resting or alert) for 90 percent of the time. They prefer to climb trees under 40 centimeters diameter and spend most time on horizontal branches or supported by multiple branches. There are no significant differences among different age groups, with the exception of young which tend to be more active than adults and more exploratory.

Lumholtz’s tree-kangaroos rest in the canopy and sleep in a curled position supported by multiple branches. Feeding takes place in the canopy or middle zone, often at the forest edge, where vines are common. The tail is used for balance, hanging low under the center of gravity. Wild Lumholtz’s tree-kangaroos tend to use the ground primarily for escape purposes; they are capable of dropping considerably distances from the canopy to the ground without hurting themselves. When on the ground they only exhibit bipedal hopping. When in trees they are capable of various movements, including hopping, individual movement of paired limbs, and use of the arms to pull themselves up.

Lumholtz’s tree-kangaroos sense using vision, touch, sound and chemicals usually detected with smell and communicate with touch, sound and pheromones (chemicals released into air or water that are detected by and responded to by other animals of the same species). Adults do not communicate much or at all with each other. However, they are capable of vocalization when agitated or disturbed. According to Animal Diversity Web: Vocalizations include a soft ‘pffft’ exhalation noise when mildly agitated and a louder ‘woof’ and moaning when more agitated. All of these noises are relatively soft, none audible from over 30 meters away by a human. Hearing is not thought to be particularly well developed in Lumholtz’s tree-kangaroos, as the pinnae (external part of the ear) are smaller than those of terrestrial macropods. The relative importance of sight and smell are not well studied. It is thought, however, that males use olfactory cues to determine when females are in estrus.

In June 2019, there were reports that many Lumholtz's tree-kangaroos were going blind. Normally they are rarely seen but at that time they began showing up at schools, sheds and in the middle of roads, unable to see and confused. Veterinarian Andrew Peters, from Charles Sturt University, said he had found evidence of optic nerve and brain damage, suggesting that a viral infection was involved. [Source: Wikipedia]

Lumholtz's Tree-Kangaroo Mating, Reproduction and Offspring

Lumholtz’s tree-kangaroos are polygynandrous (promiscuous), with both males and females having multiple partners. They engage in year-round breeding, with an average inter-birth interval is 1.4 years. The female estrus cycle is between 47 and 64 days, with an average of 56.4 days. The gestation period ranges from 42 to 48 days. The usual number of offspring is one. Females usually come into estrus about two months after their young have permanently left the pouch. There is no evidence that females exhibit postpartum estrus or embryonic diapause (temporary suspension of development of the embryo). [Source: David Kellner, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Lumholtz’s tree-kangaroo males and a females likely form brief consort relationships. They will stay together for a maximum of several days, during which copulation may occur up to three times a day. It is believed males patrol their home range, approaching females whose ranges overlap with theirs. Males use olfactory and behavioral cues to determine whether females are in estrus. Before copulation, a male repeatedly sniffs the female’s cloaca and pouch, perhaps to detect pheromones that indicate estrus. During copulation, the male positions himself behind the female, rub his head, neck, and shoulders against the cloaca, and mate.s Copulation may last from 10 to 35 minutes. In captivity, copulation occurs most frequently on the ground; however, it is not known whether this is the case in the wild. A copulatory plug inhibits later fertilization by the sperm of other males. Active mate guarding and competition have not been observed. |=|

Lumholtz’s tree-kangaroo young are altricial, meaning they are relatively underdeveloped at birth. Parental care is provided by females. Males are not involved in parenting. The average weaning and the average time to independence is 13 to 14 months. There is an extended period of juvenile learning. On average females reach sexual or reproductive maturity at age 2.04 years. On average males reach sexual or reproductive maturity at 4.6 years.

Lumholtz’s tree-kangaroo young stay in and use their mother’s pouch for about a year after birth. Joeys begin to look outside the pouch at around eight months and take make their first forays outside the pouch at approximately 10 months. At this stage mothers can be very protective, sometimes grabbing joeys and encouraging them to return to the pouch. Young continue to suckle from the mother for about a month or two after they permanently leave the pouch. Mothers invest a lot of time teaching their offspring which leaves to eat and how to maneuver safely high in the canopy. Mother-young behavioral interactions involve frequent physical contact, often initiated by the young. Juveniles may remain in their mother’s home range up to 21 months after birth.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org , National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, David Attenborough books, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2025