Home | Category: Animals / Kangaroos, Wallabies and Their Relatives

TREE-KANGAROOS

From katedolamore,com

Tree-kangaroos are marsupials of the genus Dendrolagus, adapted for living and getting around in trees. They inhabit tropical rainforests of New Guinea and far northeastern Queensland, Australia along with some of the islands in the region. All tree-kangaroos are considered threatened due to hunting and habitat destruction. They are the only true arboreal macropods (kangaroos and wallabies). Dendrolagus means “tree hare”.

There are 14 known tree-kangaroo species. When early Aboriginals told European hunters about tree-kangaroos, the hunters thought that the Aboriginals were kidding, One explorer wrote in 1872, "to entertain the idea that any kangaroo known to us, or approaching its formation, could climb a tree would be ridiculous: the animals was not formed for such work.”

The Tree-kangaroo’s rainforest habitats are being destroyed or degraded by logging, timber production and coffee, rice and wheat farming. Such habitat loss can make tree-kangaroos more exposed to predators, such as feral and domestic dogs. Tree-kangaroos are hunted by local community and this contributes significantly to their population declines. Data on the deaths if 27 Lumholtz's tree-kangaroo, which live in the rainforests of northeastern Australia, revealed 11 were killed by vehicles, six by dogs, four by parasites and the remaining six by other causes. [Source: Wikipedia]

RELATED ARTICLES:

TREE-KANGAROOS IN AUSTRALIA: BENNETT'S, LUMHOLTZ'S, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

TREE-KANGAROOS IN PAPUA NEW GUINEA: SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

TREE-KANGAROOS IN WEST PAPUA, INDONESIA: SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

PADEMELONS: SPECIES CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

MARSUPIALS: HISTORY, EVOLUTION, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

MARSUPIALS IN AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

MARSUPIALS IN AUSTRALASIA (AUSTRALIA, NEW GUINEA, NEARBY ISLANDS) ioa.factsanddetails.com

KANGAROOS AND WALLABIES (MACROPODS): CHARACTERISTICS, HISTORY, POPULATIONS ioa.factsanddetails.com

KANGAROO BEHAVIOR: FEEDING, REPRODUCTION, JOEYS ioa.factsanddetails.com

WALLABIES: TYPES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

WALLABY SPECIES ioa.factsanddetails.com

FOREST WALLABIES (DORCOPSIS): SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

Tree-Kangaroo Range, Habitat and Diet

Twelve of the 14 known species including a couple that have only been discovered relatively recently, live in New Guinea, both in Papua New Guinea and West Papua in Indonesia, and some nearby islands, namely the Biak (Schouten) Islands and the Raja Ampat Islands near West Papua, Indonesia. Two species live in Australia.

Tree-kangaroos inhabit the tropical rainforests and thrive in the treetops and upper canopy. Although most species are found in mountainous areas, several also occur in lowlands, such as the aptly named lowlands tree-kangaroo. Because they spend much of their time in trees they are good at climbing and jumping between trees and branches. [Source: Wikipedia]

Tree-kangaroos have adapted better to regions of high altitudes. They need to find places in which they are comfortable and breeding as they only give birth to one joey per year. They are known to have one of the most relaxed and leisurely birthing seasons. They breed cautiously in the treetops during the monsoon season. They have to wary of as they may fall prey to their main natural predator, the amethystine python, which also climbs and lives in the treetops.

Tree-kangaroos mainly eat leaves and fruit found in the trees where the live. They occasionally scavenge food on the ground. Tree-kangaroos will also eat grains, flowers, various nuts, sap and tree bark. Some captive tree-kangaroos eat eggs, birds and snakes, and thus are regarded as omnivores. [Source: Wikipedia]

Tree-Kangaroo History and Evolution

Most tree-kangaroos live in New Guinea. For a long time, Australia and New Guinea were joined, along with Tasmania, as part of a larger landmass called Sahul. This was the case during the last glacial period, when sea levels were lower. As the Earth warmed and glaciers melted, sea levels rose, flooding the low-lying areas and separating New Guinea and Tasmania from mainland Australia. The flooding of the Torres Strait, which separates New Guinea from Australia, is estimated to have occurred between 8,000 and 6,500 years ago, marking the final separation of Australia and New Guinea,

It is believed that tree-kangaroos may have originally evolved from rainforest floor-dwelling pademelon-like ancestors. Pademelons are some of the smallest members of the macropod family, which includes the similar-looking but larger kangaroos and wallabies. This pademelon-like ancestor possibly evolved from an arboreal possum-like ancestor that is thought to be the ancestor of all macropods in Australia and New Guinea. [Source: Wikipedia]

During the late Eocene Epoch (38 million to 33.9 million years ago), when Australia and New New Guinea began a period of drying and shrank the area of rainforest, ancestral pademelons began to begin living in a drier, rockier environment and may have evolved into rock-wallabies, which developed a generalist feeding strategy due to their dependence on a diverse assortment of vegetation refuges. This generalist strategy allowed the rock-wallabies to easily adapt to Malesian rainforest types that were introduced to Australia from Asia during the mid-Miocene (17 million to 11.6 million years ago).

Rock-wallabies that migrated into these introduced forests adapted to spend more time climbing trees. One living species of rock-wallaby in particular, the Proserpine rock-wallaby (Petrogale persephone), displays equal preference for climbing trees as for living in rocky outcrops. During the Late Miocene (11.6 million to 5.3 million years ago), semi-arboreal rock-wallabies could have evolved into the now extinct tree-kangaroo genus Bohra. Global cooling during the Pleistocene Period ( 2.58 million to 11,700 years ago) caused extensive drying and rainforest retractions in Australia and New Guinea. The rainforest contractions isolated populations of Bohra which evolved into today's tree-kangaroos. As they adapted to lifestyles in geographically small and diverse rainforest fragments and niches, they became specialized for a canopy-dwelling lifestyle and new species arose.

The extinct species Dendrolagus noibano from the Pleistocene of Chimbu Province, Papua New Guinea is substantially larger than any living species. It has since been suggested to be a larger extinct form of Doria's tree-kangaroo.

Tree-Kangaroo Characteristics

Tree-kangaroos have small hind legs and more developed forelimbs than other kangaroos. They do not hop around so much but move around in trees like a bear. Unlike their earthbound cousins, tree-kangaroos have strong forelimbs that help them clamber up trunks and negotiate branches.

Though they are similar in overall form to kangaroos, wallabies, and other macropods, however their longer forelimbs and shorter hindlimbs means that their limbs are of similar proportions and uniform width. Tree kangaroos do not have prehensile tails like some monkeys which can grab branches and serves as a fifth limb. While tree-kangaroos have long tails, these are used for balance and counter-balance when they are moving through trees, rather than for grasping.

Lumholtz's tree-kangaroos are the smallest tree-kangaroos. They have a body and head length of 48 to 65 centimeters (19 to 26 inches), and 60–74-centimeter (24–29 inch) -long tails. Males weigh an average of 7.2 kilograms (16 pounds) and females weigh 5.9 kilograms (13 pounds). Grizzled tree-kangaroos are one of the larger tree-kangaroos. They have a head and body length of 75 to 90 centimeters (30 to 35 inches), with males being considerably larger than females. They weigh 8 to 15 kilograms (18 to 33 pounds).

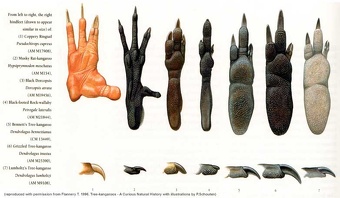

Tree-kangaroos are awkward on the ground but do hop around. Up in trees they can move around with the dexterity of a slow monkey— and even hop from branch to branch. Tree-kangaroos adaptations for their arboreal (tree-swelling) life-style include longer and broader hind feet with longer, curved nails and a sponge-like grip on their paws and soles of their feet. Tree-kangaroos have a much larger and more pendulous tail than terrestrial kangaroos, giving them enhanced balance while moving about the trees. Like terrestrial kangaroos, tree-kangaroos do not sweat to cool their bodies, rather, they lick their forearms and allow the moisture to evaporate in an adaptive form of behavioural thermoregulation.

Tree-Kangaroo Species

Tree-kangaroos in Australia:

Lumholtz's tree-kangaroos (Dendrolagus lumholtzi) live on the southeast part of Cape York, near the coast in northern Queensland

Bennett's tree-kangaroos (Dendrolagus bennettianus) live about 150 kilometers north of Lumholtz's tree-kangaroo on the eastern part of Cape York, near the coast in northern Queensland

Tree-kangaroos in New Guinea:

Grizzled tree-kangaroos (Dendrolagus inustus) live in northern New Guinea in both Papua New Guinea and West Papua in the Indonesian part New Guinea and the Bird’s Head in West Papua in the Indonesian part New Guinea

Seri's tree-kangaroos (Dendrolagus stellarum) live mostly in central West Papua in the Indonesian part New Guinea in New Guinea but part of their range extends into central Papua New Guinea; Seri's tree-kangaroos have been described as both a subspecies of Doria's tree-kangaroos and a separate species based on its absolute diagnostability

Tree-kangaroos in Papua New Guinea:

Matschie's tree-kangaroos (Dendrolagus matschiei) live in a small area near the coast of central eastern Papua New Guinea; these monkeylike marsupials have a body and head length of 50 to 81 centimeters (20 to 32 inches;, adult males weigh 9–11 kilograms (20-25 pounds) and adult females weigh 7–9 kilograms (15-20 pounds)

Doria's tree-kangaroos (Dendrolagus dorianus) live in southeast Papua New Guinea; Their body and head is 51–78 centimeters (20–31 inches), with a long 44–66 centimeters (17–26 inches) tail, and weigh 6.5–14.5 kilograms (14–32 pounds).

Ifola (Dendrolagus notatus) live in a fairly large area in central Papua New Guinea

Goodfellow's tree-kangaroos (Dendrolagus goodfellowi) live in central and southeast Papua New Guinea

Golden-mantled tree-kangaroos (Dendrolagus pulcherrimus) live in a small area near the coast in northern Papua New Guinea; they were first described as a subspecies of Goodfellow's tree-kangaroo but fairly recently has been elevated to species status based on its absolute diagnostability

Lowlands tree-kangaroos (Dendrolagus spadix) live in the lowlands central southern Papua New Guinea

Tenkile (Dendrolagus scottae) live in a couple of small areass in northern Papua New Guinea; A population of the tenkile (Scott's tree-kangaroo) recently discovered in the Bewani Mountains may represent an undescribed subspecies

Tree-kangaroos in West Papua in the Indonesian part New Guinea:

Ursine tree-kangaroos (Dendrolagus ursinus) live in the Bird’s Head in West Papua in the Indonesian part New Guinea

Dingisos (Dendrolagus mbaiso) live in a relatively small areas of central West Papua in the Indonesian part New Guinea

Wondiwoi tree-kangaroos (Dendrolagus mayri) live in small area on the southeast of the Bird’s Head in West Papua in the Indonesian part New Guinea; they were thought to be extinct until 2018 and are among the 25 "most wanted lost" species in the Global Wildlife Conservation's "Search for Lost Species"

Tree-Kangaroo Behavior

Tree-kangaroos are arboreal (live mainly in trees), scansorial (good at climbing), usually nocturnal (active at night), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), sedentary (remain in the same area) and usually solitary. They sleep about 60 percent of the time, curled up in a tree. Tree-kangaroo are often found way up in the canopy deep in remote rainforests, which is partly why they weren't discovered by Europeans until late in the 19th century.

On the ground tree-kangaroos move at approximately human walking speed and hop awkwardly, leaning their body far forward to balance the heavy tail. However, in trees, they can be quite agile. They climb by wrapping their forelimbs around the trunk of a tree and, while allowing their forelimbs to slide, hop up the tree using their powerful hind legs. When descending down tree trunks, they usually back down. They are expert leapers; nine meters (30 feet) downward jumps from one tree to another have been recorded. Tree-kangaroos have the ability to jump to the ground from 18 meters (59 feet) or more without being hurt.

Lumholtz’s tree-kangaroos rest in the canopy and sleep in a curled position supported by multiple branches. Feeding takes place in the canopy or middle zone, often at the forest edge, where vines are common. The tail is used for balance, hanging low under the center of gravity. Wild Lumholtz’s tree-kangaroos tend to use the ground primarily for escape purposes; they are capable of dropping considerably distances from the canopy to the ground without hurting themselves. When on the ground they only exhibit bipedal hopping. When in trees they are capable of various movements, including hopping, individual movement of paired limbs, and use of the arms to pull themselves up.

Lumholtz’s tree-kangaroos sense using vision, touch, sound and chemicals usually detected with smell and communicate with touch, sound and pheromones (chemicals released into air or water that are detected by and responded to by other animals of the same species). Adults do not communicate much or at all with each other. However, they are capable of vocalization when agitated or disturbed. According to Animal Diversity Web: Vocalizations include a soft ‘pffft’ exhalation noise when mildly agitated and a louder ‘woof’ and moaning when more agitated. All of these noises are relatively soft, none audible from over 30 meters away by a human.

Tree-Kangaroo Mating, Reproduction and Offspring

Little is known about the reproduction of tree-kangaroos in the wild. The only published data is from captive animals. Female tree-kangaroos reach sexual maturity as early as two years of age and males at 4.6 years. The female's estrus period is thought to be around two months. They have one of the longest marsupial offspring development/maturation periods; pouch life for the young is eight to nine months and weaning occurs three to eight months after that.

Some species of tree-kangaroo, such as Matschie's tree-kangaroo have been successfully bred and studied in captivity, but most have not. From what can be surmised, females breed annually, producing one young per litter. As they live in tropical rainforest with little differentiation between seasons, tree-kangaroos are not likely to be seasonal breeders, and, instead, are probably opportunistic breeders, breeding when food is plentiful. Captive Matschie's tree-kangaroo and Goodfellow’s tree-kangaroo have lived and remained reproductively capable for over 20 years, though this is probably less likely to occur in the wild. It is estimated that tree-kangaroos may ideally produce six offspring in a lifetime. [Source: Hien Nguyen, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

A few hours before birth, the mother begins to clean the pouch by licking it thoroughly. Then she sits down with her tail brought forward between her legs and squats with her back rounded. The single newborn emerges from the cloaca, rupturing the fetal membranes, and climbs into the pouch with no assistance from its mother, where it grows for the next ten to twelve months. Joeys continue to nurse for several months after permanently leaving the pouch, returning frequently to their mother for milk, which they obtains only from "their own" teat. [Source: Scherrie Johnson, Animal Diversity Web (ADW)]

Young accompany their mothers for up to two years, of which the first nine months is spent in the pouch. Females may exhibit embryonic diapause (temporary suspension of development of the embryo) or quiescence , in which case quiescence is most likely lactational, as with other macropods. Joeys typically remain with their mothers until developing into sub-adults, usually weighing over five kilograms. Adult males usually only contact juveniles when consorting with adult females, although males accompanying juveniles have been observed after the loss of the mother.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org , National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, David Attenborough books, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2025