AUSTRALIAN ANIMALS

Australia wildlife from a 1907 book: 1) Tawny frogmouth (bird), 2) Koala, 3) cockatoo, 4) long-billed cockatoo, 5) flying fox (Fruit bat), 6) Common brushtail possum, 7) numbat, 8) Bandicoot, 9) kookaburra, 10) glider, 11) cassowary, 12) Lyrebird, 13) Red kangaroo, 14) Dingo, 15) Horn kangaroo, 16) Echidna, 17) Platypus, 18) Tasmanian devil, 19) Thylacine (Tasmanian wolf), 20) quoll, 21) emu, 22) wombat, 23) black swan

There are about 386 species of mammals, 870 species of reptile and almost 900 species of birds in Australia. About 93 percent of the reptile species and 45 percent of bird species are endemic to Australia, meaning they are found nowhere else in the world. . Of the approximately 270 native land-dwelling mammal species in Australia, 84 percent are endemic,

Settlers often gave erroneous names to plants and animals, placing them in the wrong biological families, because they bore a passing resemblances to plants and animals found back home. One bird with a red breast, for example, was named a robin even though it was a flycatcher. [Source: David Attenborough, The Private Life of Plants, Princeton University Press, 1995]

Australia is perhaps most famous for its marsupials, which includes kangaroos, koalas, wallabies possums, Tasmanian devils, tree kangaroos, and bandicoots. Among the more unusual animals are echidnas, platypuses and wombats. There are also dingos, flying fox (fruit bat), giant saltwater crocodiles, frilled-neck lizards and the world’s most venomous snaakes and spiders. Birdlife includes bowerbirds, cassowaries, black swans, emu, galah, kookaburra, lyrebirds, anhinga, bellbirds, fairy penguin, rosella, and many types of cockatoos, parrots, hawks, and eagles. For now we won’t even get into the sea life found off Australia’s shores. [Source: “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations”, 2007]

Most of Australia's animals are plants and found nowhere else in the world. About 89 per cent of the marsupials in Australia and 73 per cent of other Australian animals are unique to the continent. The monotremes (platypus and echidnas) are found only in Australia and New Guinea. The reason the uniqueness of Australia’s animal life is because the Australian landmass broke off 65 million years from the Gondwanaland, the super continent made up an amalgamation of all of today's continents. After that Australia became isolated and its animals and plants evolved differently than those on other continents, with the exception of migrating species that could fly or swim beyond the shores of Australia. The only large landmass comparable in its isolation to Australia is Madagascar, which is also home to a large number of plant and animal species found nowhere else in the world.≤

The plant and animal life in Australia is so diverse that Australia has been labeled by international conservation groups as one of the world's 12 "megadiversity" nations. And, Australia love their wildlife and take pride in its diversity and potential dangers. According to “CultureShock! Australia”: Consider highway signs warning motorists to drive slowly because there may be ducks or kangaroos crossing. And the amazing spectacle of 1,000 volunteers up to their chests in bone-chilling sea water as they struggle to keep a school of 100 beached whales alive for hours on end.”

Book: “The Complete Book of Australian Animals”, edited by Ronald Strahan (Merrimack Publishers Circle, Salem N.C., 1986).

RELATED ARTICLES:

DANGEROUS ANIMALS IN AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

VENOMOUS ("POISONOUS") ANIMALS IN AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

ENDANGERED ANIMALS IN AUSTRALIA: SPECIES, THREATS, TRENDS, CONSERVATION ioa.factsanddetails.com

WORLD'S OLDEST LIFE FORMS: STROMATOLITES, ALGAE AND THROMBOLITES ioa.factsanddetails.com

CAMBRIAN EXPLOSION AND THE WORLD'S OLDEST ANIMALS ioa.factsanddetails.com

DINOSAURS IN AUSTRALIA: TYPES, CHARACTERISTICS, WHEN AND WHERE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ICE-AGE ANIMALS IN AUSTRALIA: WHEN, WHERE AND HOW THEY LIVED AND WENT EXTINCT ioa.factsanddetails.com

GIANT ICE-AGE ANIMALS IN AUSTRALIA: WOMBATS, KANGAROOS AND THUNDER BIRDS ioa.factsanddetails.com

MARSUPIALS: HISTORY, EVOLUTION, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

MARSUPIALS IN AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

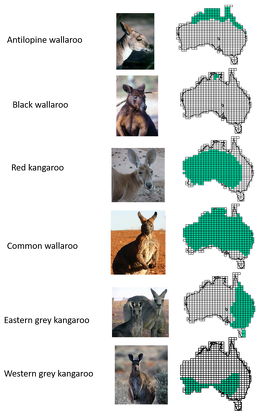

KANGAROOS AND WALLABIES (MACROPODS): CHARACTERISTICS, HISTORY, POPULATIONS ioa.factsanddetails.com

WALLABIES: TYPES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

WOMBATS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

PLATYPUSES: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

ECHIDNAS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

LIZARDS IN AUSTRALIA: TYPES, SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR ioa.factsanddetails.com

THORNY DEVILS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

FRILLED LIZARDS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

CASSOWARIES: HISTORY, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

EMUS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

BOWERBIRDS: BOWERS, TYPES, DECORATIONS, COURTSHIP DISPLAYS ioa.factsanddetails.com

LYREBIRDS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

Mammals, Reptiles, Amphibians and Birds in Australia

Australia is home to around 386 mammal species, with 364 being native and 22 introduced. This includes 2 monotremes, 154 marsupials, 83 bats, 69 rodents, and 10 pinnipeds, along with other terrestrial carnivores, ungulates, lagomorphs, cetaceans, and a sirenian.

Australia is home to approximately 270 native land-dwelling mammal species, and around 84 percent of these are endemic, meaning they are found nowhere else in the world. This includes the diverse groups of marsupials, monotremes, and other mammals. There are three types of mammals: 1) Monotremes are the oldest lineage. They lay eggs. 2) Marsupials bear tiny young they may feed in pouches. 3) Placentals include sea lions and humans. They gestate internally.

Australia is home to approximately 870 reptile species, with a high percentage (around 93 percent) being endemic. This diverse group includes turtles, lizards, snakes, and crocodiles. Australia's reptiles are particularly diverse in the arid regions of the continent. Australia is home to approximately 230 species of native amphibians, all of which are frogs, and 93 percent are endemic to the continent.

Australia is home to around 898 species of birds. This number includes those found on the mainland and its offshore islands and territories. Approximately 45 percent of these are endemic to Australia. Ilsa Sharp wrote in “CultureShock! Australia”: The hysterical cackling of Australia’s Kookaburra bird or the screech of a Cockatoo or Lorikeet for the more melodious song of a European Blackbird or Songthrush” are common sounds in Australia. “Around my suburban home in Western Australia, the chortling and burbling of Magpies, the menacing cawing of big black Australian Ravens, the shrill piping of the perky Magpie Lark, the chatter of the aggressive tail-flicking black and white ‘Willie Wagtail’ fantail, the happy chirrups of Honey-eaters, the sore-throated screech of the pink and grey Galahs and the urgent squawking of a bevy of black Carnaby’s Cockatoos overhead, all say ‘Australia’ to me in a very special way. And another thing that strikes you about Australia is the relative tameness of the wild birds, which will come very close to humans at times; that’s mainly because almost nobody harasses them, and cagebird culture is not as developed as it is in, say, Asia. [Source: Ilsa Sharp, “CultureShock! A Survival Guide to Customs and Etiquette: Australia”, Marshall Cavendish, 2009]

Wallace Line, Weber's Line and Lydekker’s Line

Animals life in Australia, New Guinea and eastern Indonesia is separated from animal life in Asia by the Wallace Line. The Wallace Line is an invisible biological barrier described by the British naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace (1823-1913). Running along the water between the Indonesia islands of Bali and Lombok, it separates the species found in Australia, New Guinea and the eastern islands of Indonesia from those found in western Indonesia, the Philippines and the Southeast Asia, which were all connected by land bridges when sea levels dropped during ice ages. Because of this tigers never ventured east of Bali and kangaroos never made it to Asia.

Map of Sunda and Sahul (marked by 125 meter depth contour), with the Wallace Line, the Weber Line and the Lydekker Line

The Wallace Line was drawn in 1859 by Wallace and named by the English biologist Thomas Henry Huxley. It separates the biogeographic realms of Asia and 'Wallacea', a transitional zone between Asia and Australia formerly also called the Malay Archipelago and the Indo-Australian Archipelago (Present day Indonesia). To the west of the line are found organisms related to Asiatic species; to the east, a mixture of species of Asian and Australian origins is present. Wallace noticed this clear division in both land mammals and birds during his travels through the East Indies in the 19th century. [Source: Wikipedia]

The Weber line is named after Max Wilhelm Carl Weber (1852 –1937), a German-Dutch zoologist and biogeographer. His discoveries as leader of the Siboga Expedition (a Dutch zoological and hydrographic expedition to Indonesia in 1899 and 1900) led him to conclude that Wallace's Line was placed too far to the west. His studies, along with others, led to a series of alternative lines delimiting the Australasian realm from the Indomalayan realm. These lines were based on the fauna and flora in general, including the mammalian fauna. [Source: Wikipedia]

Later, Pelseneer published an influential paper on this topic, in which he proposed his preferred limit Weber's Line., to honor Weber. As is the case with plant species, faunal surveys revealed that for mollusks and most vertebrate groups Wallace’s line was not the most significant biogeographic boundary. The Tanimbar Island group, and not the boundary between Bali and Lombok, appears to be the major interface between the Asia and Australasian regions for mammals and other terrestrial vertebrate groups.

Lydekker’s Line is named after Richard Lydekker (1849–1915), a British naturalist, geologist and writer. In 1896 he delineated the biogeographical boundary through Indonesia, known as Lydekker's Line, that separates Wallacea on the west from Australia-New Guinea on the east. It follows the edge of the Sahul Shelf, an area from New Guinea to Australia of shallow water with the Aru Islands on its edge. Along with Wallace's Line and others, it indicates the definite effect of geology on the biogeography of the region, something not seen so clearly in other parts of the world.

For more information on the Wallace Line See BIODIVERSITY IN SOUTHERN ASIA: WALLACE LINE, HOTSPOTS, RARE SPECIES factsanddetails.com

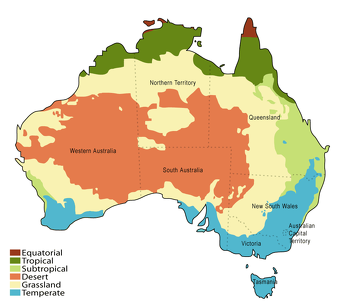

Animal Habitats of Australia

Different animals are found in Australia’s different habitats. In the rainforests. pythons, cassowaries, bandicoots and mice are the largest wild animals living on the ground. Feral foxes and pigs also live there. Possums, tree kangaroos and a monkey-like marsupial called a cuscus live in the trees. A number of colorful birds and butterflies are also found there.

The tropical wetlands supports saltwater crocodiles, pig-nosed turtles, antilopine wallaroos and many kinds of water birds. At the of the Dry (the Australian dry season) large flocks of waterbirds such as pied herons, whistling ducks and magpie geese gather in the receding swamps and lagoons.

The eucalyptus forest supports many of the animals most associated with Australia: koalas, wombats, platypus, bower birds and kookaburrras. There are also some kangaroos but not as many as in dryers areas. Other animals found in the eucalyptus forest induce echidnas, gliders, bats, and possums.

The Outback, or Central desert, supports large mobs of red kangaroos, emus, flocks of galahs and cockatoos, a variety of snakes and lizards, wedge-tailed eagles, and small marsupials such as bilbies and cyads. Many of these animals survive off spinifex grass or animals that eat it. Most species breed in the cooler winter. Eggs and young are vulnerable to attacks from dingoes and eagles.

Mice Invasions

The mouse populations in Victoria can reach plague proportions. Some granaries are infested with so many rodents they look as if they have a coat of fur. The populations soar during abundant grain harvests brought on by periods of high rainfall. When the harvests fall the population decreases as a result of disease and cannibalism. In 1931 the Nullabar Plain town of Loongana was invaded by an army of mice. It was so bad a stationmaster SOSed for help saying: "Rest is impossible. Everywhere one looks are thousands of animals which seem to have come out of the sky. They are eating everything...attacking furniture and bedding.

House mice (Mus musculus) are an introduced species in Australia. It is believed to they first arrived as stowaways on board the First Fleet of British colonists in 1788. An early localised plague of mice occurred around Walgett in New South Wales in 1871. In 1872 another plague was recorded near Saddleworth in South Australia with farmers ploughing the soil to destroy mice nests.

Mouse plagues occur periodically throughout Australia. They mostly occur in the grain-growing regions in southern and eastern Australia, as often as every four years. Aggregating around food sources during plagues, mice can reach a density of up to 3,000 per hectare (1,200 per acre). The plagues destroy crops and grain stores. Mice cause damage to homes and businesses by chewing electrical wires and invading buildings, in the process driving people nuts and impacting agricultural livelihoods.

See Separate Article: INTRODUCED ANIMALS IN AUSTRALIA: RABBITS, FOXES, CATS AND MOUSE PLAGUES ioa.factsanddetails.com

Australian Mammals Glow Under a Blacklight

In October 2020, researchers reported that platypuses fluoresce a psychedelic blue-green color under black light. The species joined a short list of mammals known to do this, including opossums and flying squirrels. After that scientists began doing more investigating, mostly with Australian mammals, and found that a number of mammals fluoresce. Cara Giaimo wrote in the New York Times: “When he heard about the platypus discovery, Kenny Travouillon, curator of mammals at the Western Australian Museum, borrowed a black light lamp from the arachnology department. (They normally use the lamps to find scorpions, which also fluoresce.) After confirming that their preserved platypuses glowed, he and his colleagues moved on to the rest of the collection. “We just went around for a bit of fun,” he said. “Putting the torch on all of them and let’s have a look.” [Source: Cara Giaimo, New York Times, December 20, 2020]

“This was only a first pass. Fluorescence occurs when pigments in certain materials absorb ultraviolet rays, which are usually invisible to people, and re-emit them as colors that we can see. Black light lamps and flashlights soak these pigments with UV rays and cause them to glow — but they often emit visible light as well, which can muddy the waters. More rigorous studies involve filtering out this visible light, and measuring the fluorescence’s true strength and color.

“But what they saw was encouraging. Bilbies — endangered marsupials with long snouts and rabbit-like ears — had orange and green accents. The quills of hedgehogs, porcupines and echidnas shone bright white, as if dipped in correction fluid. Some specimens were more reserved: Of two wombat species they examined, only one fluoresced, and “kangaroos didn’t seem to do very much at all,” Travouillon said. The museum planned to team up with a nearby university to do a more systematic study, with better equipment in 2021.

“When a co-worker told Jake Schoen, a conservation technician at the Toledo Zoo the platypus news, “we got pretty excited about it,” he said. He had already modified a camera to photograph fluorescence for another project. After checking out the zoo museum’s own preserved platypus specimen, Schoen next turned his lens on the Tasmanian devils, Spiderman and Bubbles. “The tricky part was having them sit still for a fraction of a second,” he said. Eventually, Bubbles cooperated. When the UV flash went off, voilá: A cool blue glow emerged around her eyes, at the bases of her whiskers, and inside the cups of her ears. “Presumably all of its skin is fluorescent,” Schoen said. The portrait he captured looks a bit like a velvet painting. Preserved Tasmanian devils at the Western Australian Museum glowed in a similar way, Travouillon said.

“What do the scientists who found that platypuses glow think? “These observations are exciting,” said Erik Olson, an associate professor of natural resources at Northland College in Ashland, Wisconsin, and one of the authors of the platypus paper. “Others say it’s easy to read too much into these findings. “While looking at photos of animals with Day-Glo fur or skin gives the impression that perhaps they appear this way to one another, that’s very unlikely, said Michael Bok, a visual systems biologist at Lund University in Sweden who was not involved in any of this research. “It would be incredibly surprising,” he said, if these animals “could make out these fluorescent patterns in any sort of natural lighting environment.” He compares it to human fingernails and teeth — biological materials that also fluoresce, to little fanfare or avail.

“In a 2017 paper, two biologists reviewed hundreds of known examples of fluorescing birds, plants, crustaceans and other organisms, and found only a few cases where these patterns might play a role in camouflage, mate attraction or other behaviors. Schoen and others at the Toledo Zoo hope to work with contacts at the Save the Tasmanian Devil Program to potentially “tease out whether or not this is actually an ecologically adaptive trait,” he said.

More than 100 Threatened Species Hit Hard by Australian Bushfires

More than 100 threatened species of animals and plants in Australia were hit hard by the Australian bushfires in 2019 and 2020, pushing many towards extinction. Nearly 50 threatened species — 47 plants and one spider — were believed to have had more than 80 percent of their range affected, including seven critically endangered plants. Another 65 have had more than half their area in the fire zone. The worst affected mammal is believed to be the Kangaroo Island dunnart, an endangered mouse-like marsupial endemic to the 160 kilometers long South Australian island. [Source: Adam Morton, The Guardian, January 20, 2020]

Adam Morton wrote in The Guardian: Species believed to have had at least half and up to 80 percent of their living area affected include the endangered long-footed potoroo in New South Wales and Victoria, the glossy black-cockatoo in South Australia, the Blue Mountains water skink, the rufous scrub-bird and three critically endangered turtles. They are among 331 threatened and migratory species that are believed to have had more than 10 percent of where they live in burned areas across all six states. The list includes 272 species of plant, 16 mammals, 14 frogs, nine birds, seven reptiles, four insects, four fish and one spider.

John Woinarski, professor of conservation biology at Charles Darwin University, said: “This gives us grave concern about the conservation of many threatened species in Australia.” He said it was too early to call extinctions, but that many species had almost all the entire area of their population burned. “It is all the more reason that we need urgent and sustained action to recover these species,” Woinarski said. “The emergency board is full and over-flowing.”

The analysis includes a special note on the koala, which has been the focus of local and international concern about the impact of the fires on wildlife. About 12 percent of koala range in NSW, Queensland and the Australian Capital Territory — the three jurisdictions in which it is listed as vulnerable — is believed to have been affected by fires. Koalas also live in South Australia and Victoria, but are not listed in those states.

The threatened species commissioner, Sally Box, said the results were just the first step in understanding the damage wrought by the bushfire crisis, and that the list would be refined. She said some species on the list were likely to have been worse affected than others, giving the example of the critically endangered Wollemi pine, or “dinosaur tree”. The last known natural stand of Wollemi pine is in the fire zone and it appears on the list, but the NSW government last week announced it had been saved by firefighters.

“Some species are more vulnerable to fire than others and some areas were more severely burned than others, so further analysis will be needed before we can fully assess the impact of the fires on the ground,” Box said. “Already we are seeing positive examples of threatened species having survived the fires.”

How Australia’s Animals and Plants Are Adapting to Climate Change

Ary Hoffmann wrote in The Conversation: Climate change is one of the greatest threats facing Australia’s wildlife, plants and ecosystems, Yet among this growing destruction there is a degree of resilience to climate change, as Australian animals and plants evolve and adapt. Some of this resilience is genetic, at the DNA level. Natural selection favours forms of genes that help organisms withstand hotter and drier conditions more effectively.Over time, the environmental selection for certain forms of genes over others leads to genetic changes. These genetic changes can be complex, involving many genes interacting together, but they are sufficient to make organisms highly tolerant to extreme conditions. [Source: Ary Hoffmann, The Conversation, March 28, 2017. Ary Hoffmann is a Professor at the School of BioSciences and Bio21 Institute, University of Melbourne.]

Some of this resilience is unrelated to DNA. These are “plastic” changes — temporary changes in organisms’ physical and biochemical functions that help them deal with adverse conditions or shifts in the timing of environmental events. Plastic changes occur more quickly than genetic changes but are not permanent — the organisms return to their previous state once the environment shifts back. These changes also may not be enough to protect organisms from even more extreme climates.

In Australia there is evidence of both genetic and plastic adaptation. Some of the first evidence of genetic adaptation under climate change have been in vinegar flies on the east coast of Australia. These flies have a gene that encodes the enzyme alcohol dehydrogenase. This gene has two major forms: the tropical form and the temperate form. Over the past 30 years, the tropical form of the gene has become more common at the expense of the temperate one.

Plastic adaptation due to climate change has been demonstrated in common brown butterflies in southern Australia. Female butterflies are emerging from their cocoons earlier as higher temperatures have been speeding up their growth and development by 1.6 days every decade. According to overseas research, this faster development allows butterfly caterpillars to take advantage of earlier plant growth.

In many cases, it is not clear if the adaptation is genetic or plastic. The average body size of Australian birds has changed over the the past 100 years. Usually, when comparing birds of the same species, birds from the tropics are smaller than those from temperate areas. In several widespread species, however, the birds from temperate areas have recently become smaller. This might be the direct result of environmental changes or a consequence of natural selection on the genes that affect size.

In the case of long-lived species like eucalypts, it is hard to see any adaptive changes. However, there is evidence from experimental plots that eucalypts have the potential to adapt.Different eucalypt species from across Australia were planted together in experimental forestry plots located in various environments. These plots have unwittingly become climate change adaptation experiments. By monitoring the plots, we can identify species that are better at growing and surviving in extreme climatic conditions. Plot results together with other forms of DNA-based evidence indicate that some trees unexpectedly grow and survive much better, and are therefore likely to survive into the future.

Species with short generation times — a short time between one generation (the parent) and the next (the offspring) — are able to adapt more quickly than species with longer lifespans and generation times. For species with short generation times, recent models suggest that the ability to adapt may help reduce the impacts of climate change and decrease local extinction rates.However, species with long generation times and species that cannot easily move to more habitable environments continue to have a high risk of extinction under climate change. In those cases, management strategies, such as increasing the prevalence of gene forms helpful for surviving extreme conditions and moving species to locations to which they are better adapted, can help species survive.

Yowie — ‘Australia’s Bigfoot’

Hilary Whiteman of CNN wrote: The small town of Kilcoy is not the site of the first, or even the most recent, “Yowie” sighting. But it had a monument marking an astonishing encounter decades ago, one that Tony Solano says he’ll never forget. “To this day, I am still convinced. Take it to my grave,” said Solano, who hasn’t spoken in any detail about what happened for 20 years. [Source: Hilary Whiteman, CNN, December 25, 2024]

Kilcoy is home to just 2,000 people, and there were even fewer on December 28, 1979, when Solano and a friend, then both 16, spotted something scary — and almost inexplicable — in the woods. They didn’t know what it was at the time, but the incident became folklore, and a drawcard for tourists to the small rural community, set in rolling hills about one hour north of Brisbane in the state of Queensland.

Solano said he and a friend were “armed to the hilt” during a camping trip on private property near Sandy Creek, a narrow waterway that winds almost 45 kilometers (28 miles) through the region. “We had probably three or four guns, a.22,.22 Magnum, 20-gauge shotgun solids … We were out hopefully chasing some pigs, but it never eventuated,” said Solano, of a time well before Australia introduced some of the world’s toughest gun laws.

Solano’s memories are hazier than they once were, but he says he will never forget the sounds of branches snapping, and the terror that surged through his body as his friend fired shots at a beast that loomed 2 to 3 meters (6.5 to 9.8 feet) tall in nearby bushes. The bullets missed, and the boys spent a wide-eyed night beside loaded guns before leaving their campsite to raise the alarm. After steadying their nerves, they returned a few days later with their biology teacher to make a plaster cast of its massive footprint and posed for a photo with it for the local paper, looking suitably afraid.

The town went wild. Before long, Yowie branding was slapped on everything from spoons to T-shirts and, within a year, Kilcoy got its first Yowie statue, a sculpture carved from a single beech log hoisted onto a plinth in the center of town as a warning — or a lure — for curious onlookers. The wooden Yowie stood for decades in Yowie Park, becoming a target of trophy hunters who regularly lopped off its genitals as a souvenir.

Yowie Sightings

Hilary Whiteman of CNN wrote: The small town of Kilcoy is not the site of the first, or even the most recent, “Yowie” sighting. And hunters of Australia’s version of Bigfoot are no more likely to see it there than anywhere else in the country’s vast, rugged bushland. Yet, for decades, a vacant-eyed replica of a towering, hairy beast has stared into the distance from a plinth in the center of town. It’s a monument to an astonishing encounter decades ago, one that Tony Solano says he’ll never forget. “To this day, I am still convinced. Take it to my grave,” said Solano, who hasn’t spoken in any detail about what happened for 20 years. [Source: Hilary Whiteman, CNN, December 25, 2024]

Harrison’s first encounter with a Yowie was in 1994, when he was living in a home surrounded by trees on Tamborine Mountain in southeast Queensland. “I was walking towards the front door in the dark, and there was this awful noise coming from the swamp just beyond the fence,” he told CNN. “It was guttural, really guttural. I know koalas can make some pretty horrific noises, but this is nothing, nothing like a koala.” Harrison said he heard it walking on two feet, ripping foliage from the ground with every step. “And then it would throw whatever it’s pulling out, and you can hear it hit the other trees.” Did he see it as well? “No, this is all audio. But it was absolutely horrifying,” Harrison said.

The next time was 1997, when one chased him through a field in the hinterland town of Ormeau. This time he saw it. “The way I describe it, is like a bear and a lion all in one. It was huge,” he said. An even closer encounter followed in 2009, when Harrison says he “got hit in the chest by one,” in wilderness around the tiny town of Kilkivan, north of Kilcoy. “You don’t get any closer than that,” he said. The next day, Harrison said he went for a solo hike and saw two Yowies. He didn’t have his phone on him, so wasn’t able to take a photo.

However, years later Harrison and his team took thermal imaging equipment into the mountain ranges of D’Aguilar National Park, north of Brisbane, and caught on camera what they claimed were two Yowies. Blurry images show beasts standing at least 2.7 meters (9 feet) tall, he said. It’s hard to make out the Yowies’ features, but for a team of Yowie hunters who’ve dedicated years — even decades — to finding proof that they exist, the significance was extraordinary.

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see “Australia’s Bigfoot’ watched over the small town of Kilcoy for decades. Then one day, it disappeared” By Hilary Whiteman, CNN, December 24, 2024 cnn.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org , National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, David Attenborough books, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2025