VENOMOUS ANIMALS IN AUSTRALIA

Venomous creatures in Australia — some of them with poisons strong enough to kill you — include spiders, snakes, jellyfish, octopuses, ants, bees and even platypuses. In his book “Sunburned Country”, Bill Bryson wrote that Australia “has more things that can kill you than anywhere else...This is a country where even the fluffiest of caterpillars can lay you out with a toxic nip; where seashells will not just sting you but will actually sometimes go for you...It’s a tough place,

Venomous is the correct term for animals with poison. If you call them poisonous technically that means they are poisonous to eat, like poisonous mushrooms or possibly fugu (blowfish in Japan). Ethan Freedman told Live Science, The terms "venom" and "poison" are not interchangeable. Venom is injected directly by an animal, whereas poison is delivered passively, such as by being touched or ingested. "If you bite it and you get sick, it's poisonous. If it bites or stings you and you get sick, then it's venomous," said Jason Strickland, a biologist at the University of South Alabama who studies venom. In a research article published in 2013 in the journal Biological Reviews, scientists proposed a third category of natural toxins: the "toxungens." Toxungens are actively sprayed or hurled toward their victim without an injection. For example, spitting cobras can spew toxins from their fangs.[Source:Ethan Freedman, Live Science, March 27, 2023]

Powerful toxins (lethal dose): 1) anthrax (0.0002); 2) geographic cone shell (0.004); 3) textrodoxotine in the blue ring octopus and puffer fish (0.008); 4) inland taipan snake (0.025); 5) eastern brown snake (0.036); 6) Dubois’s sea snake (0.044); 7) coastal taipan snake (0.105); 8) beaked sea snake (0.113); 9) western tiger snake (0.194); 10) mainland tiger snake (0.214); 11) common death adder (0.500). Lethal doses is defined as the amount in milligrams needed to kill 50 percent of the animals tested.

RELATED ARTICLES:

ANIMALS IN AUSTRALIA: TYPES, UNIQUENESS, HABITATS, CLIMATE ioa.factsanddetails.com

DANGEROUS ANIMALS IN AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

ENDANGERED ANIMALS IN AUSTRALIA: SPECIES, THREATS, TRENDS, CONSERVATION ioa.factsanddetails.com

WORLD'S OLDEST LIFE FORMS: STROMATOLITES, ALGAE AND THROMBOLITES ioa.factsanddetails.com

CAMBRIAN EXPLOSION AND THE WORLD'S OLDEST ANIMALS ioa.factsanddetails.com

DINOSAURS IN AUSTRALIA: TYPES, CHARACTERISTICS, WHEN AND WHERE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ICE-AGE ANIMALS IN AUSTRALIA: WHEN, WHERE AND HOW THEY LIVED AND WENT EXTINCT ioa.factsanddetails.com

GIANT ICE-AGE ANIMALS IN AUSTRALIA: WOMBATS, KANGAROOS AND THUNDER BIRDS ioa.factsanddetails.com

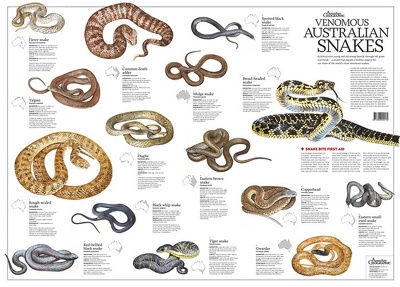

Most Venomous Snakes in Australia — and the World

1) Inland Taipans by many reckonings are the world’s most venomous snakes. According to the International Journal of Neuropharmacology their venom is very toxic and little bit can go a long way. These snakes favor in the clay crevices in Queensland and South Australia's floodplains, often within the pre-dug burrows of other animals. Because they in more remote locations than the coastal taipan, the inland taipan rarely comes into contact with humans, the Australian Museum says. A a taipan feels threatened, it coils its body into a tight S-shape before darting out in one quick bite or multiple bites. A main ingredient of this venom, which sets it apart from other species, is the hyaluronidase enzyme. According to a 2020 issue of Toxins journal (Novel Strategies for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Snakebites), this enzyme increases the absorption rate of the toxins throughout the victim's body. [Source Jeanna Bryner, Live Science, August 31, 2021]

2) Coastal Taipans live in the coastal areas of Australia and are incredibly fast, able to jump into the air fangs-first to attack a victim multiple times before they are aware of what hit them, according to the Australian Museum. When threatened, this snake, which lives in the wet forests of temperate and tropical coastal regions, lift its whole body off the ground and can jump extraordinary precision. Before 1956, when an effective antivenom was produced, this snake's bite was nearly always fatal, according to Australian Geographic. The snake's venom contains neurotoxins, which prevent nerve transmission.

3) Eastern Tiger Snakes (Notechis scutatus) have powerful venom but only kill an average of one human a year according to the University of Adelaide.. Native to the mountains and grasslands of southeast Australia and mostly brown with beige stripes, the eastern tiger snake sometimes has yellow and black bands on its body. Patterning can vary among different populations, according to the Australian Museum. Its potent venom can cause poisoning in humans in just 15 minutes after a bite.

4) Eastern Brown Snakes live mostly in eastern Australia and are responsible for more human fatalities than any other snake species in Australia. Their venom is very powerful, containing powerful toxins that can cause paralysis and internal bleeding. The initial bite is often painless, according to the Australian Museum. "They're the only snakes in the world that regularly kill people in under 15 minutes," Bryan Fry, who studies venom at the University of Queensland, told ABC News in 2024. "Even more insidiously than that is that for the first 13 minutes, you're going to feel fine." They generally hunt during the day and are often found in the suburbs of cities and large towns, putting them in close contact with humans. Many eastern brown snake bites are the result of people trying to kill them.

5) Common Death Adders are another deadly snake in Australia. Before the introduction of antivenom in the 1950s, about 60 percent of common death adder bites were fatal. According to Live Science: Common death adders are found across coastal areas of southern, eastern and northern Australia. They are recognizable thanks to their broad, triangular heads, short, thick bodies and thin tails. Common death adders are ambush predators and wait for prey — including frogs, lizards and birds — under leaves until they are ready to strike. Bites to humans are rare and normally involve a person stepping on one by accident. Their venom causes paralysis and can lead to death:

RELATED ARTICLES:

VENOMOUS SNAKES IN AUSTRALIA: VENOM, SPECIES, BITES, AVOIDANCE, TREATMENT ioa.factsanddetails.com

TAIPANS (WORLD'S DEADLIEST SNAKES): SPECIES, VENOM, BITES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR ioa.factsanddetails.com

TIGER SNAKES: CHARACTERISTICS, REGIONAL MORPHS, VENOM, BITE VICTIMS ioa.factsanddetails.com

BROWN SNAKES: SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, VENOM, BITE VICTIMS ioa.factsanddetails.com

PYTHONS IN AUSTRALIA: SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

VENOMOUS SNAKES: THEIR VENOM, BITES AND ANTIVENINS factsanddetails.com ;

VENOMOUS SNAKES AND HUMANS: BITES, ANTIVENINS, WHAT TO DO factsanddetails.com;

Funnel Web Spiders — the World’s Deadliest Spiders

The funnel web spider is recognized as the deadliest spider in the world. Native to Australia, its venom contains 40 different toxic proteins, according to Mount Sinai School of Medicine. This spider was responsible for several human deaths in the Sydney area, but no deaths have been reported from a funnel web spider in Australia since 1980. [Source: Olivia Munson, USA TODAY, February 26, 2023]

Native to Australia and New Zealand, atrax spiders, which include the funnel web spider, are said to be "very large, very poisonous, very aggressive; lunges at prey or in self defense...Bite: painful...may include muscle spasm, profuse sweating, high blood pressure, fluid in lungs, coma."

According to the BBC the funnel-web spider is also one of the most aggressive and deadliest creatures on Earth. It is incredibly defensive, and because of this can bite several times in a single attack. The bite itself is very painful, and symptoms can arise quickly. If a bite is left untreated it can lead to serious illness and even death. Children are especially susceptible to bites and must be taken to hospital as soon as possible if bitten. [Source: James Cutmore, BBC, November 2, 2024]

Deadly Cone Snails

Deadly cone snails are found in Australian waters. All cone snails are venomous and capable of stinging. The sting of many of the smaller species is roughly equivalent to a bee or hornet sting, but the sting of a few of the larger tropical fish-eating species, such as Conus geographus, Conus tulipa and Conus striatus, can be fatal. Other dangerous species include Conus pennaceus, Conus textile, Conus aulicus, Conus magus and Conus marmoreus.

Cone snails have been described as "the deadliest creatures on the planet, for their size." Small creatures with beautiful shells found in the South Pacific and Indian Oceans, they inject venom with short barbs into their victim. The poison can cause paralysis an even death in fish and humans. Humans are rarely deliberately attacked. Deaths and injuries often have been the result of divers innocently pocketing the shells and finding out the harpoons can penetrate swimsuits.

Symptoms of a cone snail sting may include an excruciating pain at the penetrated area, much worse than a bee’s sting. As the pain fades, numbness soon sets in, followed by dizziness, slurred speech, and respiratory paralysis. Death can follow within half an hour afterward, but this is rare. Presently, there is no known anti-venom. Applied pressure on the wound, immobilization and artificial respiration (mouth-to-mouth resuscitation) are the only recommended treatments for victims. [Source: Miranda Hall, Animal Diversity Web (ADW)]

Related Articles: DEADLY CONE SNAILS: CHARACTERISTICS, TOXINS, DEATHS AND DRUGS ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

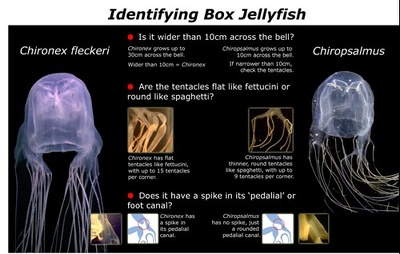

Box Jellyfish

The box jellyfish — which is found off mostly of the north and northeast coast of Australia and to a lesser degree in Southeast Asia — is arguably the world’s most venomous creature. Victims sometimes die within three minutes and over 80 people have died from their stings off of Queensland alone since 1880. What makes them particularly dangerous is the fact that their translucent box-shaped bodies and 60 spaghetti-like tentacles are difficult to see. They are also known as marine stingers or sea wasps. [Source: William Hammer, National Geographic August 1994]

Box jellyfish, named for their body shape, have tentacles covered in biological booby traps known as nematocysts — tiny darts loaded with poison. People and animals unfortunate enough to be injected with this poison may experience paralysis, cardiac arrest, and even death, all within a few minutes of being stung.But of the 50 or so species of box jellyfish only a few have venom that can be lethal to humans.

Very little is known about box jellyfish. Scientists have traditionally observed them underneath piers feeding on fish attracted to light, and no one had ever kept one alive in captivity until 1977. Now scientists studying keep them in disk-shaped aquariums with circulating in a current that is similar to natural conditions. Strangely enough the box jellyfish was not even identified until 1956. Before that time there were reports of swimmers leaping out of the water in agony not having any idea what caused the stringy red welts and the inferno of pain.

Related Articles:

BOX JELLYFISH: CHARACTERISTICS, SPECIES AND VENOM ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

BOX JELLYFISH: STINGS, VICTIMS AND DEATHS ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

PORTUGUESE MAN-OF-WAR: CHARACTERISTICS, REPRODUCTION AND STINGS ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

Blue-Ringed Octopuses

Blue-ringed octopuses are the most well-known venomous octopuses. The name Blue-ringed Octopus is actually given to a group of octopods consisting of four different species: 1) the greater blue-ringed octopus (Hapalochlaena lunulata), 2) the southern blue-ringed octopus (Blue-ringed octopus), 3) the blue-lined octopus (Hapalochlaena fasciata) and 4) the common blue-ringed octopus (Hapalochlaena nierstraszi). These octopuses are small enough to fit in the palm of your hand. The greater blue-ringed octopus has larger rings than the blue-ringed octopus and is most commonly found on Australia's northern coast. Theblue-lined octopus, has lines instead of rings on its body and is found only in New South Wales. [Source: Ashleigh MacConnell, Animal Diversity Web (ADW); [ Harry Baker, Live Science, March 27, 2023]

All octopuses produce venom, but only a few can cause death to humans. Three or four species of closely-related blue ringed octopus rank with some cone shells for the title of the world's most poisonous mollusks — and for that matter the most poisonous creature in the sea. Residing in the waters off of Australia, Indonesia, and parts of Southeast Asia, these species of octopus carry a toxin capable of killing a person in minutes, with some carrying enough toxin to kill 10 people. Fortunately the octopus are not aggressive, and bite only when taken out of the water and provoked.

See Separate Article: BLUE-RING OCTOPUSES AND VENOMOUS OCTOPUSES ioa.factsanddetails.com

Why Does Australia Have So Many Venomous Animals?

One answer to question above relates to the geological history of the Australian continent. Australia became a separate landmass about 100 million years ago when it split from the southern supercontinent Gondwana, Kevin Arbuckle, an associate professor of evolutionary bioscience at Swansea University in the U.K. told Live Science. The venomous insect lineage is two to three times older than this separation, he said. [Source: Elana Spivack, Live Science, November 26, 2023]

Elana Spivack wrote in Live Science: Put another way, some already venomous species simply got stuck on Australia when it became an isolated landmass. Venomous arthropods there include trap-jaw ants (genus Odontomachus), which can inflict a painful bite; but these insects also live in other tropical and subtropical regions around the world, not just Australia. Similarly, Australian bulldog ants (genus Myrmecia), which can simultaneously sting and bite, are among the deadliest ants in the world and have reportedly killed three people since 1936, according to Guinness World Records. These venomous ant lineages were already on Gondwana at the time of separation and stayed there once Australia became its own continent.

As for spiders, funnel-web spiders (genera Hadronyche and Atrax) are the only exclusively Australian ones that can kill humans with a venomous bite, Arbuckle said. Male Sydney funnel-web spiders (Atrax robustus) are thought to have killed 13 people, although no human deaths have been recorded since antivenom was introduced in 1981, according to the Australian Museum. An Australian species of widow spider, the redback (Latrodectus hasselti), can also kill with a venomous bite. Their ancestors, too, predate Australia as a separate continent. Likewise, venomous cephalopods, including squid, octopus and cuttlefish, have existed for up to 300 million years. They've lived in the surrounding waters for eras before Australia existed on its own.

Another part of this answer stretches back 60 million years to "an accident of history," according to Michael Lee, a professor of evolutionary biology at the South Australian Museum and Flinders University. Back then, continental drift pushed Australia over the frigid South Pole, which wiped out most of its reptiles. When the continent slowly drifted northward, it warmed up and attracted reptiles once again. By chance, 40 million years after this "accident," the first snakes colonized the continent — and they happened to be from the venomous front-fanged Elapidae family, which includes cobras, mambas, coral snakes and taipans. They became the land's snake ancestors, which then evolved into more venomous snakes. Of Australia's 220 snake species, 145 are venomous, Lee told Live Science via email. These deadly serpents account for 65 percent of Australia's snake population, though only about 15 percent of the world's snakes are venomous.

As for jellyfish, every species is venomous. They also date back over 500 million years and have been floating through the ocean since before Australia existed. While deadly box jellyfish (such as Carukia barnesi) and Portuguese man o' war (Physalia physalis) reside in Australian waters, Arbuckle emphasized that these creatures populate tropical and subtropical waters, not just those Down Under. They're a "not particularly Australian phenomenon," he said. Rather, Australia's coastline fosters an ecosystem fit for these creatures.

Enumerating just how many venomous creatures Australia hosts is difficult. "The short answer is lots, and probably more than [we] think," Dieter Hochuli, an ecology professor at the University of Sydney, told Live Science. Aside from snakes, however, Arbuckle argued Australia's venomous fauna are actually well within typical range. "Contrary to popular belief, Australia isn't particularly abundant or diverse in venomous invertebrates," he told Live Science. "Australia has a remarkably enduring and prominent image as the home of highly venomous animals, yet for the most part this is overstated." He wondered if part of this belief stems from the continent's "scientific capital" and "excellent infrastructure" for public health and medical care. "Its venomous animal diversity is not unusual at all for a largely tropical area," Arbuckle said.

Queensland Particularly Rich in Toxic and Venomous Creatures

Queensland has a lot of toxic and venomous animals. Robert George Sprackland wrote in Natural History magazine: Generally speaking, some of the most fertile grounds for bioexploration are tropical reef communities. Such reefs harbor a phyla-spanning host of organisms that produce powerful toxins. So it is no surprise that Queensland, whose coastline includes the entire Great Barrier Reef, is home to the widest array of toxic creatures in Australia. [Source: Robert George Sprackland, Natural History magazine, October 2005]

Some 300 species of cone shells live in and around the reef, each with a venom that may include as many as a hundred distinct chemicals — yielding perhaps several thousand biochemically interesting compounds. Also among the well-armed sea fauna of Queensland are all ten of the most dangerous sea snakes in the world. Many other Queensland creatures — including various species of fishes and mollusks — hold the distinction of being the most venomous of their kind. There are also box jellyfish.

The diversity of wildlife in Queensland is hardly limited to sea creatures. In the rainforest of the tropical north, more species of flowering plants are thought to occur within a few typical acres than are found in all of North America. Among the land fauna are nine of the ten most venomous land snakes in the world. And new species from northern Queensland are still being discovered and formally described every year; many more are still unknown to science. There is plenty in Queensland to keep bioexplorers busy for a long time.

Scientists Seeking Useful Drugs from Toxic Animals in Australia

In Brisbane you have Gehrmann Laboratories where the Venom Evolution Lab is housed, and the the Queensland Bioscience Precinct. Wilson da Silva wrote in Australia Geographic: In the midst of this $130 million showpiece, completed in 2002, stands the palm-fringed Institute for Molecular Bioscience. Between them, these two locations have some of the most sensitive, fancy and expensive scientific instrumentation in Australia, much of which is designed to coax insights from the tiniest fragments of molecules. At the institute there are 21 high-tech microscopy facilities, and an auditorium-sized mass spectrometer able to do 100 scans per second to a resolution of less than one part per million, identify 1200 proteins an hour and map the plethora of peptides in a venom. All of this is backed by high-powered graphics-accelerated computers for image processing and visualisation. [Source: Wilson da Silva, Australia Geographic, January 28, 2021

In this hive of 21st-century scientific bravura, some 400 scientists probe the genetic and molecular basis of living things, seeking to apply their findings to the design of new drugs or the development of new treatments that improve health, combat disease or make cities and food more sustainable. “This is the centre of the world in terms of venom research,” says Professor Glenn King, a biochemist at the institute. “There are other places doing excellent work in antivenom research, and groups in Belgium and Melbourne doing great work on venom toxins, but in terms of research breadth across drug development, pharmacology, chemistry and structural biology, we’re definitely the leaders.”

In 2005, Robert George Sprackland wrote in Natural History magazine: In Brisbane, laboratory workers at a six-year-old biotechnology company called Xenome Ltd have the unenviable task of “milking” cone shells. The job is not an easy one. Because the snail can bend its proboscis to sting from virtually any angle, there is no safe way to hold a live cone shell. To get the venom, the technicians dangle a small fish from forceps for the snail to sting. The snail’s venom kills the fish, but it can then be safely extracted from the fish’s tissue. In spite of that roundabout — and costly — procedure, Xenome’s efforts have been worthwhile. The company is developing a drug based on cone-shell toxin for treating severe long-term pain. Its effects are similar to those of morphine, but because of its potency, effective doses are smaller, and so far at least, it seems not to be addictive. [Source: Robert George Sprackland, Natural History magazine, October 2005]

Xenome’s work is an outgrowth of a major bioprospecting project in Australia, initiated in 2003 by Peter Beattie, the premier of Queensland, and his government. Known as the Queensland Bioscience Precinct, the project aims to encourage the discovery of new biochemicals that might spawn major pharmaceutical products. What sets apart the Queensland bioexplorers is that they focus on molecules derived from animals, instead of from plants. At least 25 percent of the medicines currently available come from plant products, but relatively few animals so far have been assessed for medically useful chemicals. Thus, animal bioexplorers are entering largely uncharted territory, and the odds are good, they believe, that a mother lode is still out there, waiting to be discovered.

If animal toxins, and their therapeutic potential, are such underexplored pharmaceutical territory, why do so many bioexplorers converge on Australia? Things that sting and bite, after all, occur around the world. The answer is as straightforward as the whereabouts of a gold rush: you go where the yield is most likely to be high. Not only do countless venomous animals live Down Under, but some, such as certain species of cone shells, may also produce toxins with a lengthy list of ingredients. (By contrast, the venom of a typical highly venomous snake may include only a handful of chemical components.) Bill Bryson was exaggerating only slightly when he claimed to have looked up a particular animal in the fictitious “Things That Will Kill You Horridly in Australia, volume 19.” Part of the scientific recognition that Australia is such a rich potential source of new animal toxins can be traced to the work, in the 1950s, of Hugo Flecker, a naturalist and physician living in Cairns, Queensland (See Box Jellyfish). The sea wasp was dramatic proof that there were still dangerous unknown creatures to be discovered and studied. Since Flecker’s time many other toxic marine organisms have been described, and their study has been conducted in a more systematic way.

Australian Venom Scientists

Wilson da Silva wrote in Australia Geographic: Researching venom can be a hazardous pursuit. Ask Associate Professor Bryan Fry. This Brisbane-based molecular biologist has been bitten 27 times by venomous creatures, mostly snakes on land and box jellyfish and stingrays at sea. He’s also had 23 broken bones and 400 stitches, has been concussed three times and once fractured his spine in three places, after which he spent months in hospital relearning how to walk. [Source: Wilson da Silva, Australia Geographic, January 28, 2021

Bryan is no masochist. But if you study venom, you need to go into some wild places and confront a lot of deadly creatures to collect the material that’s fundamental to your research. It may be dangerous, but it’s necessary, because Bryan’s work with the venoms he collects is crucial to making the antidotes — the antivenoms — needed to treat the millions of people bitten around the world each year by venomous animals.

Of course, there’s no one antivenom that works across all species: each needs to match the toxins of a particular species. To make matters more complicated, the toxins can vary widely within the same species, depending on the environment they live in and the prey they take. Without a detailed understanding of exactly what’s in a venom, it’s not possible to predict how the human body will react to it, what organs will be affected and how to treat a patient.

“There is a global database of antivenoms maintained by the World Health Organization, but it’s based on what is known about each species of snake,” explains Bryan, who heads the Venom Evolution Lab at the University of Queensland (UQ). “How well these have been tested against the full geographic range of any particular snake, or how it performs against snakes that are close relatives and may therefore have some cross-reactivity, we just don’t know.”

Much of the lab’s time is taken up delving into the extraordinary complexity of venoms. And that means so much more than just determining what toxins make up the venoms of the world’s venomous creatures. It’s often also about exploring the sometimes-sizeable toxin variability between geographic ranges of the same species. And it can be about investigating what elements of one antivenom might work across related or unrelated species — known as cross-reactivity.

To do all this, the lab’s researchers rely on the world’s most diverse venom collection — ranging from Antarctic octopuses, king cobras and Komodo dragons to vampire bats — much of it collected during Bryan’s two decades of fieldwork.

Understanding venoms is essential, because envenomation — being bitten by a venomous animal — is a huge global problem. Around the world about 5.4 million people a year are bitten by venomous snakes alone. Between 81,000 and 138,000 of them die. Venoms not only kill but can cause paralysis, bleeding disorders, kidney failure and tissue damage, all of which can lead to limb amputation or other permanent disabilities. Children suffer more severely because of their smaller body mass.

As one of the world’s leading venom specialists, Bryan is an author on almost 250 scientific papers and has led 40 field expeditions to collect venoms. And he’s contacted by people from all over the world, sometimes in the middle of the night, asking for help.

“I get phone calls at two in the morning from researchers who are assisting doctors to treat bite victims,” he says. “I recently consulted on a bite in Brazil, of somebody who kept a pet cobra illegally, and one veteran researcher asked, ‘What’s this cobra’s venom likely to do?’ It was one we’d worked on, so I said, okay, in addition to the paralysis, for which they’ll need artificial respiration, this cobra’s venom also affects the muscles. So you need to monitor for muscle breakdown…and [possible] kidney failure.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org , National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, David Attenborough books, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2025