Home | Category: Animals / Birds, Crocodiles, Snakes and Reptiles

CASSOWARIES

Cassowaries are among the largest land animals in Australia and New Guinea. Bigger than emus and most kangaroos, they are second heaviest bird in the world after ostrichs and the third tallest birds after the ostrichs and emus. Cassowaries stand as tall as a 1.8-meter (6-foot) man and can weigh over 60 kilograms (121 pounds). One shot in 1880 weighed 83 kilograms. Cassowaries can live 40-50 years in the wild. Age has been estimated based on the appearance of the casque (See Below), the size of the footprint, and the presence of wrinkles on the neck.

Cassowaries are large flightless birds. Cousins of emus, they have colorful plumage and live in the rain forests of northern Queensland and New Guinea in both Papua New Guinea and Papua and West Papua in Indonesia, some islands around New Guinea and Seram and Aru Islands in the Moluccas of Indonesia. The family Casuariidae includes three living cassowary species, all of the genus Casuarius. Their previous distribution may have been wider, and the current distribution may not reflect natural ranges, as cassowaries have been hunted and traded by humans for hundreds and maybe thousands of 500 years. [Source: Danielle Cholewiak, Animal Diversity Web (ADW)]

Cassowaries has even described as "monstrous purple turkies." They are prized as a source off food by tribesmen in New Guinea. In addition to There is a lot of variation between different birds ans as many as 17 subspecies of cassowary have been described but none of them are universally recognized. The Australia species, the Southern Cassowary, is the largest. Ostriches, emus and rheas belong the ratite family of big flightless birds.

Olivia Judson wrote in National Geographic: Two species are confined to the rain forests of New Guinea and nearby islands. The southern cassowary lives in the Wet Tropics of northern Queensland, in the part of Australia that sticks up at New Guinea like a spike. Some live deep in tracts of rain forest, such as the Daintree; others live on the forest edge and may wander through people’s backyards. But a cassowary is not your regular garden bird. If an adult male stretches up to his full height, he can look down on someone five feet five — i.e., me — and he may weigh more than 110 pounds. Adult females are even taller, and can weigh more than 160 pounds. ...Most of the time, however, cassowaries seem smaller than they are, because they don’t walk in the stretched-up position but slouch along with their backs parallel to the ground. [Source: Olivia Judson, National Geographic, September 2013]

three cassowaryspecies: southern cassowary (left); northern cassowary (middle); dwarf cassowary (right)

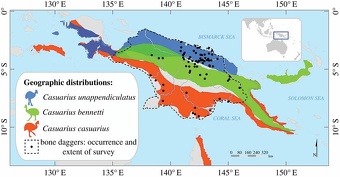

The three cassowary species:

Southern cassowaries (Casuarius casuarius) are also known as double-wattled cassowaries. They live in southern New Guinea, northeastern Australia, and the Aru Islands, mainly in lowlands. They are a species of least concern on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List.

Northern cassowaries (Casuarius unappendiculatus) are also known as single-wattled cassowaries. The can be found in northern and western New Guinea, and Yapen, mainly in lowlands. They are classified a species of least concern on the IUCN Red List.

Dwarf cassowaries (Casuarius bennetti) are also known as Bennett's cassowaries. They occur in New Guinea, New Britain, and Yapen, mainly in highlands. They are a species of least concern on the IUCN Red List.

RELATED ARTICLES:

CASSOWARIES AND HUMANS: HISTORY, SIDE BY SIDE, ATTACKS ioa.factsanddetails.com

SOUTHERN CASSOWARIES: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

CASSOWARIES OF NEW GUINEA: SPECIES, WHERE THEY LIVE, WHAT THEY'RE LIKE ioa.factsanddetails.com

EMUS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

EMUS AND HUMANS: MEAT, OIL, RANCHING AND WARS ioa.factsanddetails.com

MOAS: HISTORY, CHARACTERISTICS, REPRODUCTION, EXTINCTION, DE-EXTINCTION? ioa.factsanddetails.com

MOA SPECIES: GIANT, SMALL AND HEAVY-FOOTED ONES ioa.factsanddetails.com

BIRDS OF AUSTRALIA: COMMON, UNUSUAL AND ENDANGERED SPECIES ioa.factsanddetails.com

BOWERBIRDS: BOWERS, TYPES, DECORATIONS, COURTSHIP DISPLAYS ioa.factsanddetails.com

BOWERBIRD SPECIES: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

LYREBIRDS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

KOOKABURRAS: CHARACTERISTICS, LAUGHING, BEHAVIOR, SPECIES, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

PARROTS OF AUSTRALIA-NEW GUINEA: SPECIES, COLORS, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR ioa.factsanddetails.com

COCKATOO SPECIES: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

COCKATOOS: COLORS, DIET, LONG LIFESPANS, DANCING, VOCALIZATIONS, HUMANS ioa.factsanddetails.com

BIRDS: THEIR HISTORY, CHARACTERISTICS, COLORS factsanddetails.com ;

BIRD FLIGHT: FEATHERS, WINGS, AERODYNAMICS factsanddetails.com ;

BIRD BEHAVIOR, SONGS, SOUNDS, FLOCKING AND MIGRATING factsanddetails.com

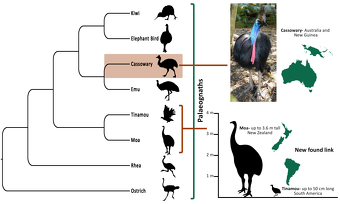

Ratites

Cassowarres are ratites, a group that embraces all flightless birds that lack a keel (a ridge of bone that extends outward from the breastbone on which flight muscles of flying birds are attached). Ratites are comprised of six extant families and some extinct families. The five families are Aptergyidae (kiwis), Casuariidae (cassowaries), Dromaiidae (emus), Rheidae (rheas), Tinamidae (Tinamous) and Struthionidae (ostriches). The family for the elephant bird is the extinct ratite family Aepyornithidae. The "moa family" belong the extinct Dinornithiformes. Ratites They are mostly large, long-necked, and long-legged, with the exceptions being the kiwi, which is also the only nocturnal extant ratite, and tinamous which can fly. Ratites were previously known as Struthioniformes. The name ratite is derived the birds’ raft raft-like sternum. [Source: Wikipedia, Ellie Bollich, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Derek Grzelewski wrote in New Zealand Geographic: The name ratite, from ratis, Latin for raft, refers to the birds’ sternum, which is flat and raft-like, lacking a keel to which flight muscles could be attached. The sterna of flighted birds have a keel to which their large flight muscles are attached, and these birds are sometimes termed carinates (from the Latin carina, a keel). Just to confuse the issue, though, some ratites — the South American tinamous, for example — have a keeled breast-bone and can fly. On the other hand, the kakapo, whose parrot relatives can fly extremely well, have a sternum as flat as that of any kiwi or moa. [Source: Derek Grzelewski, New Zealand Geographic. January-March 2000]

It was first thought that ratites shared a common flightless ancestor on the ancient supercontinent Gondwana, which later fragmented, leading to the diversification of ratites on different continents. However, modern genetic studies suggest that ratites may have lost the ability to fly independently and the ancestors of living ratites diverged relatively recently, after the breakup of Gondwana. This suggests that the loss of flight occurred in different ratite lineages — an example of convergent evolution, the process by which distantly related animals independently evolve similar traits or features as a result of adapting to similar environments or ecological niches.

Evidence suggests that ratites might have evolved flightlessness multiple times, with different lineages developing similar traits (such as large size, reduced wings) in response to similar environmental pressures. For example, kiwis, despite being geographically close to other ratites, are more closely related to extinct elephant bird, suggesting independent evolution of flightlessness. Tinamous, small, flying birds from South America, are also now considered to be part of the ratite lineage, further complicating the picture.

For more on this See Ratites and Their Evolution Under MOAS: HISTORY, CHARACTERISTICS, REPRODUCTION, EXTINCTION, DE-EXTINCTION? ioa.factsanddetails.com

Cassowary History and Evolution

ranges of cassowary species: northern cassowaries (Casuarius unappendiculatus); dwarf cassowaries (Casuarius bennetti); southern cassowaries (Casuarius casuarius)

Ostriches of Africa, rheas of South America and emus and cassowaries of Australia-New Guinea and are believed to have evolved from flying birds. The bones of their stunted wings are fused together like the wings of flying birds. Their feathers, however, are different. They lack the hook and barb system of flying bird feathers that make them aerodynamic. No doubt this system has been lost as the birds flew less.

Ostriches, rheas and emus and cassowaries are believed to have evolved from three different families of flying birds, with emus and cassowaries evolving from the same one and ostriches and rheas each evolving from different ones. They are this good examples of convergent evolution — the process by which distantly related animals independently evolve similar traits or features as a result of adapting to similar environments or ecological niches.

Cassowaries are closely related to emus; some classification schemes group them within the same family. It appears they evolved from a common ancestor in Australia, but the time of their divergence is still unclear. A fossil thought to be an intermediate form between cassowaries and emus dates back to the late Oligocene Period (33 million to 23.9 million years ago) and Early Miocene (23 million to 16 million years ago) [Source: Danielle Cholewiak, Animal Diversity Web (ADW)]

The three species of cassowary are found abundantly in the fossil record dating back to the Upper Pleistocene Period (125,000-11,000 years ago), and earlier fossils have been found from the Late Miocene Period (11.6 million to 5.3 million years ago) and early Pliocene Period (5.4 million to 2.4 million years ago). |=|

Cassowary Characteristics

Southern cassowaries are the largest of the three cassowary species. Adults are 1.5 to 1.8 meter (4.9 to 5.9 feet) tall, although some females may reach 2 meter (6.6 feet) and weigh 58.5 kilograms (130 pounds). It is not uncommon to see exceptionally large females weighing more than 70 kilograms (150 pounds). The largest southern cassowary ever recorded weighed 85 kilograms (187 pounds) and 190 centimeters (6.3 feet) tall. Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present: In general, the sexes are fairly similar, though females are slightly larger and more brightly colored, and have larger casques. Cassowary males and females look pretty much the same when they're young, but females may eventually grow about 30 centimeters (a foot) taller.

Cassowaries have striking metallic blue or purple necks with bright red, yellow or blue lobes of flesh called wattles. Color patterns vary from bird to bird and can be used to identify individuals. The dark brown or black hairlike plumage that covers the bodies of cassowaries is difficult to see in the shady rainforest. Their drooping plumage of cassowaries is black and different than that of other large flightless birds. Ostrich feathers are soft and fluffy. Rheas, which endure older weather, have long, shaggy feathers. As is the case with emus, each cassowary feather has a double shaft of equal length. The only noticeable part of the wings are five quills.

Olivia Judson wrote in National Geographic: “Their feathers are glossy black; their legs are scaly. Their feet have just three toes — and the inside toe of each foot has evolved into a formidable spike. Their wings are tiny, having shrunk almost to the point of nonexistence. But their necks are long, and bare of all but the lightest coating of short, hairlike feathers. Instead the skin is colored with amazing hues of reds and oranges, purples and blues. At the base of the neck in the front, a couple of long folds of colorful skin, known as wattles, hang down. Cassowaries have large brown eyes and a long, curved beak. On their heads they wear a tall, hornlike casque. You need only see two or three to know that unlike, say, sparrows, cassowaries can easily be recognized as individuals. This one has splendid long wattles and a straight casque; that one has a casque that curves rakishly to the right.This clear individuality, together with their size and the fact that they do not fly, makes them strangely humanlike. [Source: Olivia Judson, National Geographic, September 2013]

Cassowaries have strong, thick, heavy legs with powerful thigh muscles and large feet. They can run at speeds up to 50 kilometers per hour (30 miles per hour), and can jump 1.5 meters (5 feet) from a standing position. No one knows for sure how fast cassowaries can run. Unlike emus that run through the open outback, cassowaries run through the rain forest and have to negotiate through obstructions such as trees, shrubs, vines and creeks. The dagger-like claws on their innermost toes can be deadly weapons. Cassowaries jump and kick with both feet to defend themselves.

Two cassowary species — northern and southern cassowaries — have the distinctive wattles, which are long folds of unfeathered skin that hang from the neck. The wattles are brightly colored; colors vary by region and may change with mood of the bird. The hair on the neck is velvety. Other distinctive features, according to Animal Diversity Web, include an extremely long aftershaft, nearly as long as the main feathers (similar to Emus), and remiges that are reduced to bare quills and curve under the body. Their wings are stunted, with a smaller body-to-wing proportion than in some other ratites, and, like most other ratites, cassowaries have no tail feathers. They have small, rudimentary clavicles, a small procoracoid process, no syrinx, and reduced caeca. They have three toes like most ratites, and short middle phalanges. [Source: Danielle Cholewiak, Animal Diversity Web (ADW)]

Cassowary Casque

Unlike emus and ostriches, cassowaries don’t have feathers on their heads and necks. On the top of their its head is a brown hand-size, horny head ornaments called a casque, which is made from keratin, the same material in human fingernails and hair. In some species the casque is flattened. In other species it rises like a helmet.

All three cassowary species possess a casque, which grows slowly throughout the bird's first few years. Olivia Judson touched a cassowary. She wrote: “The skin on her neck was velvety. And her casque was not hard, as I had expected, but spongy. Olivia Judson , National Geographic, September 2013]

The function of the casque is poorly understood. It was originally thought that cassowaries used it to push aside underbrush as they travel through the dense forests. However, more recently they have been observed using it to push aside forest litter in search of food on the ground. The casque may also be important in social dynamics, as it signals age of the individual. The casques may amplify deep acoustic sounds made by cassowaries. There are also theories that they serve as helmet protecting the bird from falling seeds where they forage, or from collisions with trees as they sprint through the forest. [Source: Danielle Cholewiak, Animal Diversity Web (ADW); Rumble, November 13, 2020]

Brendan Borrell wrote in Smithsonian magazine: It's an odd structure, neither horn nor bone; it has a hard covering but is spongy inside and somewhat flexible overall. Some researchers have speculated that cassowaries use the strange protuberance...as a weapon for settling territorial disputes. Ornithologists in New Guinea have proposed another function: amplifier. They reported seeing cassowaries inflate their necks, vibrate their bodies and emit a pulsing boom that drops below the threshold of human hearing. "An unsettling sensation," is how one author described standing in front of a thrumming bird. [Source: Brendan Borrell, Smithsonian magazine, October 2008]

Cassowary Diet and Feeding Behavior

Cassowaries feed mainly on fruit, bulbs and insects. Any protein consumed by a cassowary is completely digested, even bones. Cassowaries follow regular routes through the forest and feed on fruit according to their availability throughout the year. In captivity, cassowaries are fed a mixture of fruits and dog or monkey food as a protein source. They eat almost 19 liters of fruit and almost a liter of a protein source a day in captivity.

Cassowaries eat fruits found in the rain forest floor that are poisonous to humans. They don’t get sick because their digestive system is very short and toxic substances are excreted as waste before they can be absorbed. Some fruits are found in cassowary droppings with skins still intact. Cassowaries have very active livers and unusual combinations of stomach enzymes that also may play a role in getting rid of the toxins.

Scientists studying cassowary scat have identified the seeds of 300 plant species. Describing such cassowary scat, Olivia Judson, wrote in National Geographic: “On the ground in front of me there’s a large round pile of what looks like moist purple mud. It’s roughly the volume of a baseball cap, and it’s studded with berries and seeds — more than 50. Some of the seeds are larger than an avocado stone. I kneel down to look more closely. Putting my nose just a couple of inches away, I take a sniff. It smells of fruit mixed with a whiff of vinegar. There’s also a hint of that mouth-puckering, astringent flavor you get from strong black tea. Peculiar. But not unpleasant. [Source: Olivia Judson, National Geographic, September 2013]

Cassowary Behavior

Cassowaries are generally solitary animals. They generally only join up with other cassowaries during the mating season or when food supplies are low. During the breeding season you can find them in pairs and in the nesting season you can find males with young. Cassowaries have home ranges up to seven square kilometers (2.7 square miles). They regularly patrol their ranges to keep intruders out. The shape and size of the range varies with the season and the food supply.

Cassowaries are generally shy birds and usually avoid humans. To see one is rare as they are very good at disappearing into the forest long before they are discovered. However, cassowaries travel regular paths in the forest and establish regular crossing points at rivers.

Cassowaries have poor eyesight. They produce grunting, snorting and bellowing noises that sound more like those of a beast than a bird. Cassowaries are capable of producing a low frequency boom sound that is at the lower limit of human hearing, and is the lowest frequency sound produced by any bird. It is believed that this helps them communicate with each other in dense brush. [Source: Rumble, November 13, 2020]

When threatened solitary cassowaries usually quickly retreat and crash through the forest with their feet hitting the ground like drum beats. Males protecting eggs are another story. They will fight rather than retreat. Cassowaries attack with their feet. A single blow from cassowary feet can rip open a man's stomach. Humans have been killed by such attacks, as males can be extremely aggressive when protecting nests or young.

Cassowaries fight with their beaks and wings and particularly their legs and claws. They have three toes on each foot. The long-nailed inner claw can be used as a lethal weapon. Male cassowaries use their razor-sharp spikes on both inside toes. They can inflict great damage with these spikes and their powerful kick.

Cassowary Breeding Behavior

Cassowaries nest on the ground in thickets. The breeding season starts in May or June. Females and males stay in the separate territories for most of the year. During the breeding season females cross over into there territories of nearby males and males can become more aggressive, hissing and growling and even letting out ferocious roars.

Males claim territories and pair with a female for a period of several weeks, during which time she lays three to five eggs. The eggs weigh about half a kilogram (one pound) and are green with a rough surface. After the female lays a clutch of eggs she wanders into the territory of another male and mates with him. Each male she mates is given a clutch of eggs. .[Source: Danielle Cholewiak, Animal Diversity Web (ADW)]

Cassowaries start breeding at age four or five and can live 40 years or more. After females abandons their eggs males build a rudimentary nest on the forest floor. Male cassowaries incubate the eggs, raise the chicks and remain with them for nine months. Males never leave the nest when the eggs are incubating, which is about 50 days, and doen't eat or drink during that time.

Cassowary Young

Cassowaries have the third largest eggs in the animal kingdom behind ostriches and emus. Ostrich eggs weigh 1100 grams, emus eggs weigh 637 grams and cassowary eggs weigh 584 grams.

Cassowary chicks are about the sizes of chicken and have brown or black and white stripes running across the back. They look sort of like extra large ducklings. Chicks losse their stripes after a few months “become a pretty ugly-looking mousy brown". After about a year, they begin developing adult colors and develop wattles and casques on top of their head. Young cassowaries do not fully gain adult plumage for three years.

Cassowary chicks are raised by their fathers. Brendan Borrell wrote in Smithsonian magazine: After they hatch, they follow the male for six to nine months as he protects them from predators such as wild pigs and dogs, and guides them to fruit trees within a home range several hundred acres in size. [Source: Brendan Borrell, Smithsonian magazine, October 2008]

When cassowaries become adolescents they are banished from the home range of their father's. They wander off establish their own territories and attempt to locate food sources. Many cassowaries die at this stage because they can not find enough food and are vulnerable to attacks from predators or get disoriented.

Cassowaries, the Rainforest and Seed Dispersal

Cassowaries are forest-dwelling birds who live mostly in rainforests and move around on the ground through trees and bushes in a hunched position with their heads held in more horizontal position than a vertical one. All three cassowary species require a large volume and diversity of fruit for their diet year-round but are generally segregated by altitude, ranging from lowland swamp forests to higher altitude montane forests.

Scientists studying cassowary scat have identified the seeds of 300 plant species, making the bird a key player in spreading rain-forest plants over great distances. Cassowaries are the main distributors of the seeds of more than 70 species of rainforest tree, most of whom have seeds that are too large for other forest creatures to eat. If cassowaries did not disperse the seeds over a large area these trees would only be found in isolated areas. Cassowaries play an important role in the distribution of the seeds of 80 species other rainforest plant. Many of these have seeds that are toxic to other animals. Other are consumed by small animals such as rat-kangaroos that damages the seeds and make them unable to sprout.

Olivia Judson wrote in National Geographic: In the course of a day a single adult cassowary eats hundreds of fruits and berries. Cassowary digestion is gentle, though, and does not harm the seeds, which emerge intact. And so, as a cassowary wanders through its territory, eating, drinking, bathing, and defecating, it moves seeds from one part of the forest to another — sometimes over distances of half a mile or more. It also moves seeds up hills and across rivers. In short, it transports seeds in ways that gravity alone cannot. By means of their fruit-scented droppings, then, cassowaries are a powerful vehicle for spreading seeds around. [Source:Olivia Judson, National Geographic, September 2013]

“And for a lot of trees, cassowaries are the only vehicle. Australia does have other fruit-eaters — small birds, bats, and marsupials such as the musky rat-kangaroo, a furry creature with a pointed face, big ears, and a long, naked tail — but these are too small to carry big fruits very far. And in the rain forest, many trees produce big, heavy fruits with big, heavy seeds, because such seeds grow better in the gloom of the forest floor.

“As animals roam around, eating fruit and passing seeds, they create the forest of the future: They give plants new places to grow. Thus, as fruit-eaters-in-chief, cassowaries are also chief architects of the forest. They help some plants to sprout too. Ryparosa kurrangii, for example, is a tree known only from a small region of Australia’s coastal rain forest. One study showed that without passing through a cassowary, only four percent of Ryparosa seeds grow; after passing through a cassowary, 92 percent do. (Why this makes such a difference is not known.) And so, if the cassowary were to vanish, the structure of the forest would gradually change. Trees of some species would become less widespread, and some species would probably disappear altogether. Which would be a shame.

Threats to Cassowaries

There used to be tens of thousands of cassowaries in Queensland and their range extended from Townville to Cookstown. Now there only between 1,500 and 4,000 are left between Port Douglas and Cookstown. Cassowaries populations have been hurt by destruction of habitat, illegal hunting, fragmentation of habitats by roads and communities, dogs (which are especially dangerous to young and adolescent cassowaries), foreign diseases, competition from feral pigs, and cars. In Queensland large chunks of cassowary rain-forest habitat has been cleared for sugar cane and banana plantations.

Cassowaries that live close to humans, feed on crops and other human foods. Some get used to hand outs and being feed. These birds are more vulnerable than untame birds. They approach too close to cars and dogs.

Olivia Judson wrote in National Geographic: “How many are left? This is the most contentious question in cassowary biology. In Australia the bird is listed as endangered; most tallies put the number of cassowaries around 1,500 to 2,000. But these are guesstimates: No one knows for sure. [Source: Olivia Judson, National Geographic, September 2013]

“What is clear is that cassowaries have problems. Feral pigs may destroy cassowary nests, and cassowaries sometimes die in pig traps. Another hazard is traffic. In Mission Beach, a pretty seaside town south of Cairns, several cassowaries are killed on the roads every year. I saw one victim, lying in the back of a pickup truck belonging to the Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service; the ranger had collected it right after the accident was called in. It was a young female, just on the edge of sexual maturity. Her casque was small, and she still had a few brown feathers. The bed of the truck was smeared with blood, and muck was oozing out of her mouth. Her legs were scraped. Her eyes were open but unseeing.

“The ranger was visibly upset, and talked in a steady stream about local cassowary politics, explaining how some groups want to fence off the roads and build underground tunnels for cassowaries to use, while others argue this won’t work, and lobby instead for lower speed limits and more cassowary-crossing signs. “There have been three dead birds in the last six weeks,” he said. He lifted the body out of the truck and put it in a freezer, to await an autopsy. As he did so, another cassowary appeared from behind a building, a jarring contrast between the majesty of the living and the mangled body of the dead.

“Roads also carve up the forest. And as the forest becomes more fragmented, it becomes harder for young cassowaries to find their own territories. Because these birds are so territorial, it takes a certain amount of suitable habitat to sustain a population at all. Which brings me to the other big problem: development. In Mission Beach a development called Oasis is typical. It has paved streets with names like Sandpiper Close, lined with streetlamps. But there are no houses yet: just empty lots, the grass neatly mown, garnished with For Sale signs. The only inhabitants are a flock of ibises, sheltering from the sun in the shade of the few remaining trees.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org , National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, David Attenborough books, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2025