Home | Category: Animals / Animals

ECHIDNAS

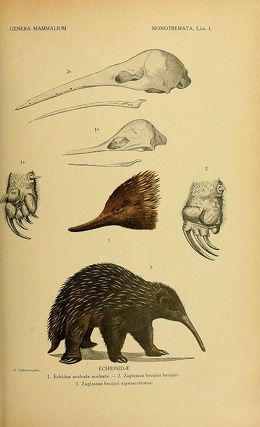

Echidna species: 1) Western long-beaked echidnas (Zaglossus bruijni); 2) Eastern long-beaked echidnas (Zaglossus bartoni); 3) Sir David's long-beaked echidnas (Zaglossus attenboroughi); 4) short-beaked echidnas (Tachyglossus aculeatus)

Echidnas (the family Tachyglossidae) are also known as spiny anteaters. Found on the Australian mainland, and in Tasmania and the highlands of New Guineas, they are porcupine-, hedgehog-like animal with a twist. Like platypuses, they are egg-laying mammals called monotremes that don’t have teeth, and though they both produce milk, they secrete it through their skin for babies (often called puggles) to lap at, because they lack nipples [Source: Amanda Schupak, CNN, May 2, 2025]

Echidna live on land and are covered in pointy quills. They have rear feet that face backward, which kick dirt out of the way as the animal burrows into the ground. Echidnas eats ants and termites and have a long sticky tongue like anteaters and pangolins..

The family Echidnas consists of two genera; Tachyglossus and Zaglossus. The genus Tachyglossus comprises one species — short-beaked echidnas (Tachyglossus aculeatus) — while Zaglossus is composed of the long-beaked echidnas of which there are three species: 1) Western long-beaked echidnas (Zaglossus bruijni), which live in highland forests; 2) Sir David's long-beaked echidnas (Zaglossus attenboroughi), discovered by Western science in 1961 and described in 1998, which prefer a still higher habitat; and 3) Eastern long-beaked echidnas (Zaglossus bartoni), of which four distinct subspecies have been identified. [Source: Neilee Wilhelm, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

All echidnas species have similar morphological features but long-beaked echidnas as their name suggests have longer snouts. They are also larger in size and have less spikes than short-beaked echidnas. Long-beaked echidnas are also located solely in New Guinea, whereas short-beaked echidnas are found in New Guinea, Australia, and Tasmania.

RELATED ARTICLES:

SHORT-BEAKED ECHIDNAS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

LONG-BEAKED ECHIDNAS: SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

PLATYPUSES: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

PLATYPUSES AND HUMANS: CONSERVATION, THEFTS, VENOM ioa.factsanddetails.com

Monotremes

Platypuses are monotremes (egg-laying mammals). All of the world's monotremes are found in Australia or New Guinea They are the platypus and four species echidnas. Regarded as "living fossils," they are relatives of early reptile-like mammals called prototherians and are more closely related to reptiles than birds. Monotremes are a different class of mammals than marsupials. Regarded as the ancestors of mammals that preceded all the other mammals living today, they don't have mammary glands with nipples. They instead have patches of skin that "weep" milk. Mammalian features of montremes include body hair and young nourished on milk. Reptilian features include a bare snout and egg-laying anatomy.

“There’s plenty of weirdness to go around on these little things,” Dr. Guillermo W. Rougier, a professor of anatomical sciences and neurobiology at Kentucky’s University of Louisville, told CNN. “They are one of the defining groups of mammals,” Rougier said. “The typical mammal from the time of dinosaurs probably shared a lot more biology with a monotreme than with a horse, a dog, a cat or ourselves.” Therefore, he said, monotremes provide a window into the origins of mammals on Earth. [Source: Amanda Schupak, CNN, May 2, 2025]

Monotremes belong to the order Monotremata. They are endothermic (use their metabolism to generate heat and regulate body temperature independent of the temperatures around them), but they have unusually low metabolic rates and maintain a body temperature that is lower than that of most other mammals. [Source: Anna Bess Sorin and Phil Myers, Animal Diversity Web (ADW)]

See Separate Article: MONOTREMES: HISTORY, EVOLUTION, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

Echidna Habitat, Range and Lifespan

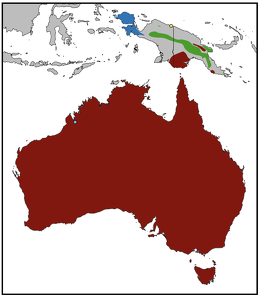

Echidna range: Short-beaked echidna (rusty red); 2) Western long-beaked echidna (blue); 3) Eastern long-beaked echidna (green); 4) Sir David's long-beaked echidna (yellow)

Short-beaked echidnas are distributed throughout the entire continent of Australia including Tasmania and eastern and southern New Guinea. Long-beaked echidnas are endemic to New Guinea but fossil records suggest populations were once in Australia.[Source: Neilee Wilhelm, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Short-beaked echidnas live a a large range of habitats as long as there are ants and termotes and ground and soil suitable for their burrowing lifestyle. Long-beaked echidnas have a narrower range and are confined to New Guinea due to their need for a humid environment. Short-beaked echidnas can survive in more arid environments as their diet provides the moisture necessary for survival. Short-beaked echidnas can inhabit anywhere from temperate or tropical forests to sandy deserts. Both genera of echidnas have specialized feet for digging and burrow for shelter. There has been evidence of short-beaked echidnas temporarily residing in abandoned rabbit burrows for cover.

Home ranges of echidnas is highly variable based on their location, but males' ranges are typically twice the size of that of a female’s. Overlap between ranges of two individuals may occur, but territory does not lead to hostility between the two. There is no home den that individuals continue to reside in, but nursery burrows may be constructed by females during reproduction periods.

Monotremes are relatively long-lived animals. Echidnas live up to 20 years in the wild and between 30 to 50 years in captivity.

Echidnas: Rare Case of Mammals Evolved from Living in Water to Living on Land

Echidnas probably evolved from a water-dwelling ancestor, according to a study published in April 28, 2025 in the journal PNAS, upending scientists' assumptions about the usual path of mammal evolutionary. "A fair few mammals have evolved from living on land to living in the water, but for an animal to go the other way is very rare," Sue Hand, a vertebrate paleontologist at the University of New South Wales in Australia, told Live Science. Chris Simms wrote in Live Science: Previously, researchers thought echidnas and their semiaquatic relative, platypuses, descended from a land-roaming animal, with the ancestors of platypuses then venturing into the water. Both animals are monotremes.[Source: Chris Simms, Live Science, May 1, 2025]

To shed more light on echidna evolution, Hand and her colleagues reexamined a humerus (upper forelimb bone) from the extinct monotreme Kryoryctes cadburyi, which lived in what is now southern Victoria, Australia, 108 million years ago, during the Cretaceous period. This species may have been an ancestor or relative of both modern platypuses and echidnas, according to the researchers. Whether K. cadburyi lived exclusively on land has been debated. Previous analysis of the bone, which was — discovered at a site called Dinosaur Cove, in the early 2000s revealed that it looked similar to bones found in echidnas.

By examining the surfaces of bones, scientists can discern clues about how related animals may be, Hand said, but what's inside the bone can reveal hints about the animals' lifestyles. So the team did micro-CT scans to view the internal microstructure of the bone. "Modern platypuses today have distinctive bones," Hand said. "They have very thick bone walls, and echidnas are almost the opposite, having quite thin bone walls. So, we were really interested to see what their common ancestor might have looked like." Despite resembling an echidna bone on the surface, the ancient humerus had thicker walls and a reduced cavity for bone marrow. "We were surprised to find that the internal structure looked more like a platypus than an echidna," Hand said. Such heavy bones would act like ballast, making it easier for the animal to dive below the water's surface. This means that K. cadburyi was likely a semiaquatic burrower and that the monotreme family used to be semiaquatic, the researchers concluded.

The ancestors of echidnas then moved permanently onto land, and their bones became lighter as they adapted to a new way of life, the researchers said in the study. Because of the dearth of fossils from platypus and echidna ancestors, it's not clear when this transition to the land happened. Most of their extinct relatives have been identified solely from their teeth and jaws, and the K. cadburyi humerus is the only monotreme limb bone from that period discovered so far.

There are many instances in which mammals have evolved from living on land to living wholly or partly in water. These animals include whales, dolphins, seals and beavers, Hand said. But it's virtually unheard of to see mammals evolve in the opposite direction. "It has happened before in the fossil record, but the more aquatic a mammal becomes, the harder it would be to go back to land," she said. However, mammals that are semiaquatic burrowers, like modern-day platypuses, would be the ideal group for being able to go either way, she said. This is because they are adapted to both land and water.

This isn't the only clue that echidnas have a watery past. When echidnas are developing, their beaks have receptors for detecting small electrical currents — which in other animals are typically used for finding prey in the water. Platypuses have even more of these receptors. In addition, echidnas' hind feet, which are used for burrowing, point backward, much like platypuses' hind feet, which the animals use like a rudder when swimming. "Platypus-like fossils date back 100 million years, but the oldest echidna fossils are less than two million years old," said Tim Flannery, a paleontologist at the Australian Museum in Sydney, who wasn’t involved in the research. "The paper adds to the evidence that echidnas had platypus-like ancestors, and is another brick in the wall in what is becoming an irrefutable case," Flannery told Live Science.

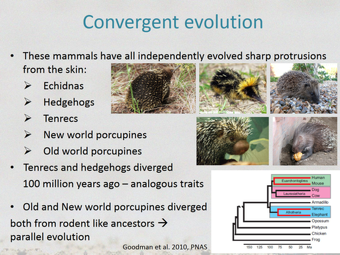

Convergent Evolution of Hedgehogs, Porcupines and Echidnas

Marion Rae of Reuters wrote: Once upon a time, millions of years ago, the humble hedgehog spread over Africa, Asia and Europe, while a freak of nature gave Australia the spiky echidna. Australia is home to the dianthus erinaceus or hedgehog plant, the chocolate hedgehog cake and the common hedgehog slug, and US porn star Ron "Hedgehog" Jeremy calls Australia home, but the lovable hedgehog is nowhere to be found on the vast continent which was cast adrift at least 200 million years ago. Curiously, the hedgehog made famous by writer Beatrix Potter and Australia's echidna often fall victim to mistaken identity, along with the spiny porcupine familiar to North Americans. [Source: Marion Rae, Reuters. August 13, 2003]

From Quizlet

Yet they are, in fact, one of the world's clearest examples of convergent evolution, say scientists. Convergent evolution, the emergence of chance look-alikes, involves an evolutionary pattern in which completely unrelated species share similar traits because each has independently adapted to similar ecological and environmental conditions. "If you were a little animal and you eat insects you have to be on the ground, then one of your main problems in life is that you get eaten by big things, so you have to come up with a defense mechanism," said Erna Walraven, senior curator at Sydney's harborside Taronga Zoo. "Both hedgehogs and echidnas, independently, have come up with spikes," Walraven said.

The hedgehog is essentially an insect-eating mammal and the porcupine is a large plant-eating rodent, while the echidna is part of an elite group of monotremes — along with the Australian platypus — which are a mixture of mammal and reptile. "If you go back 200 million years ago, you have a number of different animal mammal groups evolving in different spots and in different ways," said Anne Musser, convergent evolution specialist at the Australian Museum.

About 350 million years ago, Antarctica, India, Australia, Africa and South America formed a single landmass, a southerly "supercontinent" named Gondawana by scientists. Australia, Antarctica and South America were all joined as East Gondawana before Australia separated and moved north as the landmass broke up, while Antarctica moved south and froze over. "As Gondawana separated the animals that were marooned were the ones that were able to evolve into what we have now — marsupials made it south in time to get aboard the ark that was Australia," Musser said. The hedgehog became part of northern hemisphere history and the American porcupine flourished in its own ark.

While people often refer to Australia's echidna as a cousin of the hedgehog, Taronga Zoo's Walraven said hedgehogs and echidnas were as far removed from each other as they could be. The reproductive system is what typifies the difference. The echidna, a monotreme, has a pouch, lays eggs and then suckles its young. The hedgehog gives birth to "hoglets", usually four to six offspring at a time. Their tiny spines are covered with a membrane which shrivels away and hardens within hours. The young echidna hatches after about 10 days incubation and will then remain in its mother's pouch for seven to eight weeks. During this time it gradually becomes spiky. There are many species of hedgehogs, given their almost global distribution, but the one most commonly referred to — and fictionalized by children's writer Beatrix Potter with her Mrs. Tiggy-Winkle hedgehog character — is the erinaceus europaeus. Hedgehogs are usually brown and yellow and have an immensely developed stomach muscle which allows them to curl up into a ball for protection when they are frightened. It eats bugs and berries and has a penchant for slugs, bird eggs and snakes.

Australia's echidna is about 40-55 centimeters long, the erinaceus europaeus hedgehog is 20-25 centimeters long with a round body, stiff spines and a hairy underbelly. The echidna, one of the oldest unchanged creatures in the world, likes to live in the bush and comes out at night to eat ants and termites with its sticky tongue. There are more than a dozen species of hedgehog found throughout Africa, Asia and Europe, including the British Isles, where they feast on the eggs of now endangered birds. The American porcupine, about 75 centimeters long when fully grown, has quills protecting its back, sides and tail, which usually lie flat against its body until the animal is faced with danger.

RELATED ARTICLES:

HEDGEHOGS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION, HUMANS factsanddetails.com

HEDGEHOG SPECIES factsanddetails.com

PORCUPINES IN ASIA factsanddetails.com

Echidna Characteristics

Echidnas have the lowest body temperature of any mammal, with a normal temperature range of 22.2̊ to 24.4̊C (72̊ to 75.9̊F). Atill, they are endothermic (use their metabolism to generate heat and regulate body temperature independent of the temperatures around them) and homoiothermic (warm-blooded, having a constant body temperature, usually higher than the temperature of their surroundings). |=|

Echidnas have a long tubular snout and spines on their back like those of porcupines and hedgehogs. Echidnas are covered in brown or black fur. Short-beaked echidna spines are typically yellow, fading to black at the tip. Long-beaked echidnas have fewer spines that are white, gray, or black.

Short-beaked echidnas can be 30 to 45 centimeters (11.8 to 17.7 inches) in length and weigh from 2.5 to seven kilograms (5.5 to 15.4 pounds). Their beak is approximately half the length of the head and their short tail, is 10 centimeters (four inches or less. Long-beaked echidnas are a little larger: ranging from 60 to 100 centimeters (two to 3.3 feet) in length and weigh five to 10 kilograms (11 to 22 pounds). Their beak length ranges from 10 centimeters to 15 centimeters (four to six inches). This length creates a downward curve in their beaks.

Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is not present: Both sexes are roughly equal in size and look similar. [Source: Neilee Wilhelm, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Like platypuses, echidnas lay have poisonous spurs but aren't any reports of anyone being seriously hurt by one. Like platypuses, in which only males have venomous spurs, both male and female echidnas have spurs with venom but it seems either there is less venom or it is less toxic than that of platypuses.

While echidnas lack teeth, their extended snouts have pores for electroreception and sticky tongues to assist in achieving a meal. They have short stout legs with long claws for digging. Their hind feet are also pointed backward, which gives them an unusal gait. The hind feet also have a spur on the inner ankle.

Echidna Food and Eating Behavior

Echidnas are primarily carnivores (eat meat or animal parts) and insectivores (eat insects). Short-beaked echidnas feed primarily on termites, ants and their eggs larvae but also eat beetles, their eggs and larvae, and earthworms. Long-beaked echidnas diets are mainly earthworms and possibly other subterranean arthropods. This limiting factor is hypothesized to be a reason for the limited range of this genus.

The long snout of echidnas helps them root out ants in the soil. Their tongues are ideal for lapping in arthropods. Echidnas lack teeth. Instead they have keratinous rows of spines on their palate to grind prey. Psuedoteeth on their tongue help them grind the termites. Short-beaked echidnas forage for invertebrates by digging and often rip apart rotting logs with their claws.

Short-beaked echidnas have a sticky tongue that can reach up to 18 centimeters (seven inches) to lasso in invertebrate prey. The tongue is made sticky by mucous secreted from their sublingual salivary glands. Short-beaked echidnas in arid environments get sufficient water by consuming only termites. The tongue of long-beaked echidnas is not sticky and only extends about two to three centimeters from their elongated snout but they do have rows of keratinous spines for grinding prey. [Source: Neilee Wilhelm, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

For echidnas in zoos, getting enough ants for them to eat is difficult and the they generally don’t fancy mealworms or crickets, which are insects commercially available to zookeepers. Instead they are fed cat food mixed with fiber, which replaces the carbohydrates chitin, which forms the outer skeleton of ants.

Echidna Behavior

Echidnas are fossorial (engaged in a burrowing life-style or behavior, and good at digging or burrowing), nocturnal (active at night), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), sedentary (remain in the same area) and employ aestivation (prolonged torpor or dormancy such as hibernation). [Source: Neilee Wilhelm, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Echidnas are generally solitary except in the breeding season and when females are with young. They . burrow in the sand or live in rock crevasses. When threatened, echidnas rolls into a spiky pincushion ball, with only their snout and claws exposed.

Echidna hind feet are oriented backwards. This serves them well when they are digging, and they are indeed efficient diggers, but it also gives them a unique, awkward-looking gait that has been described as rolling and wobbling from side to side. Their unusual hind limb bones and claw structures allows echidnas to use their claws for grooming.

Echidnas may go into torpor when they experience food shortages, dependent on season and climate. This occurs during the cold season, from April to July. Both body temperature and metabolic rate decrease. Short-beaked echidnas enter torpor for short periods based on resources, not weather.

Echidnas sense and communicate with sound, vibrations, touch and chemicals usually detected with smell. Due to their solitary nature, communication between echidna individuals has rarely observed. They have of electroreceptors in their beak that are mainly used to detect vibrations and movements of prey but may also be used to communicate. Echidna make grunting noises when startled. [Source: Neilee Wilhelm, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Echidna Mating, Reproduction and Offspring

Echidnas are oviparous, meaning that young are hatched from eggs, and are polygynandrous (promiscuous), with both males and females having multiple partners. They engage in seasonal breeding — from July to August. Echidnas are typically solitary outside of mating. Males seek out females, and several follow her, forming what is colloquially called an "echidna train". Males then battle to for the opportunity to mate with the female. [Source: Neilee Wilhelm, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Echidnas only have one young a year. Like platypuses, they lay eggs and nurse their young on milk. Female echidnas lay thimble-size eggs in a fur-lined, pouch-like fold in the skin of their belly for about 10 days until a small "puggle" (baby echidna) breaks free using a bird-like egg tooth. The puggle remains in the fold after birth, taking in large quantities of milk and growing at very fast rate.

Echidnas become sexually mature between five and 12 years of age. They have one external opening called a cloaca for expelling waste and reproduction. Males have penises made for only copulation. The penis is bifurcated and forked at the end, giving the males a four-headed penis. Females produce one small, nearly round, leathery egg from the cloaca and transfer it directly to their pouch where it incubates for an average of ten days. Mothers prepare for hatching in this time by finding or digging a burrow. Observances of captive echidnas breeding in the Perth Zoo demonstrate nearly identical patterns to that of reproduction in the wild.

Parental care is carried out by females. Young (puggles) are altricial, meaning they are relatively underdeveloped at birth. Puggles are pink and hairless, weighing only 0.3 grams, when they hatch. They remain in the pouch-like skin fond for around 50 days, where they lap up milk. Female echidnas do not have teats. Instead they have milk patches on their skin where milk simply leaks out. After the pouch period is over mothers are able to leave the young in a burrow to forage for food. They return every five to six days to feed the puggles. When mothers leave the den, they cover the entrance with soil to keep their young safe from predators. Young echidnas become independent at one year old.

Four-Headed Penis of the Echidna Male

Echidna males have bifurcated penis that is forked at the end, giving them a four-headed penis.

Both short-beaked and long-beaked echidnas have penises with four heads. While the penis has four distinct tips, only two are used at a time during mating. Scientists have observed that echidnas alternate between the two functional tips during multiple ejaculations. Echidnas are unique among mammals: they are the only ones that have four-headed penises.

Although the echidna penis has four heads, only two of them become erect and functional during mating. Echidnas alternate which two heads they use, allowing for multiple ejaculations without significant pauses. This unusual anatomical feature has been the subject of scientific study to understand its purpose and function.

The echidna penis is very unusual amongst mammals. The four heads are actually rosette-like glans (cone-shaped vascular bodies at the end of the penis or clitoris): Only two of these four glans ever become functional during erection and which glans are functional appears to alternate between subsequent erections.[Source: Dr Jane Fenelon and Professor Marilyn Renfree,University of Melbourne, and Associate Professor Stephen Johnston, University of Queensland, Pursuit, June 9. 2021

According to scientists at the University of Melbourne and University of Queensland: Most mammals have a single urethral tube which carries the semen to the penis tip. The echidna urethra starts as a single tube, but toward the end of the penis it splits into two and each of these then splits again – resulting in each of the four branches ending up at one of the four glans. We’re not sure exactly why they only use two glans at any one time. It’s possible that it’s to do with male competition for females. By alternating the use of each side our tame echidna can ejaculate 10 times without significant pause, potentially allowing him to out-mate less efficient males.

How the Four-Headed Echidna Penis Works

Exactly how male echidnas were able to use their four-head penises in the way they do has always been a mystery. But June 2021, scientists announced, in a study published in the journal Sexual Development that for the first time we have untangled what is going on anatomically, based on observations of echidna at Currumbin Wildlife Sanctuary on the Gold Coast, which has established a small breeding colony of echidnas. [Source: Dr Jane Fenelon and Professor Marilyn Renfree,University of Melbourne, and Associate Professor Stephen Johnston, University of Queensland, Pursuit, June 9. 2021

According to scientists at the University of Melbourne and University of Queensland: Around 50 injured echidnas are brought to the wildlife hospital at Currumbin every year, the majority from road accidents. Unfortunately, many of these echidnas are hurt beyond recovery and have to be euthanised. It’s these animals we used for the study, but we were also able to observe a tame echidna. To understand the mechanisms at work we used microCT (Computer Tomography) scanning in combination with microscopy techniques. A normal CT scan, which uses computer technology to make 3D images from X-rays, only picks up mineralised (hard) tissue, but by staining the penis with iodine we could pick up the soft tissue details. This meant we could create a 3D model of the whole echidna penis and its important internal structures in order to see how it operates.

Initially, we thought we’d find some sort of valve mechanism on the urethra when it first started branching to control the one-sided action seen in our tame echidna. Instead, we found that the erectile tissues that make up the echidna’s penis are a very unusual. All mammalian penises consist of two erectile tissues, the corpus cavernosum and the corpus spongiosum. The main role of the corpus cavernosum is to fill up with blood and maintain an erection. The corpus spongiosum also fills up with blood, but its main role is to ensure that the urethral tube remains open at erection so that semen can pass through. In most other mammals, both the corpus cavernosum and the corpus spongiosum start off as two separate tissues at the base of the penis but then the corpora spongiosa merge into one. In the echidna, the corpora cavernosoa merge into one structure and the corpora spongiosa remains as two separate structures.

Furthermore, we found that the major blood vessel of the penis also splits into four branches following the branching of the urethra. In effect, this means that the end of the echidna penis acts like two separate glans penises. Blood flow can be directed down one side of the corpus spongiosum or the other to control which half becomes erect and which branch of the urethra remains open.

The study shows that the echina penis has more similarities to those of turtles and crocodiles. Some marsupials like the bilby also have a split urethra, but these split into two branches only and, in these species, it’s the corpora cavernosum that separates into two structures when the urethra splits.Previous studies had suggested that the echidna resembled some snakes and lizards which have hemipenes (split penises). However, we found that the echidna penis had some similarities to those of crocodiles and turtles. For example, some turtles have a five glans penis, which appears to have a similar internal anatomy.

There’s some evidence that the penis in all amniotes (reptiles, birds and mammals) has the same evolutionary origin. Our study shows that while the echidna penis is mammalian in origin – it has some evolutionary innovations all of its own. This is probably because they don’t need to use their penis for urine, so they didn’t have the evolutionary constraints of other mammals to stick to the standard penis design. Regardless, the echidna penis functions efficiently to transfer sperm directly to the female reproductive tract.

Echidna Venom Could Help Treat Diabetes

In December 2016, in a study published in Nature’s online journal Scientific Reports, Australian researchers announced that they had discovered that a hormone produced in both platypus and echidna venom could hold the key to treating type-2 diabetes. Sofia Charalambous wrote in Australian Geographic: Research led by Professor Frank Grützner at the University of Adelaide and Associate Professor Briony Forbes at Flinders University in Adelaide has revealed that a hormone usually produced in the gut of both humans and animals is actually also found in the venom of Australia’s iconic monotremes, the platypus and the echidna.[Source: Sofia Charalambous, Australian Geographic, December 6, 2016]

The hormone, known as glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), is produced by all animals to stimulate the release of insulin to lower blood glucose. Typically, it degrades pretty quickly and because of its short life span, it’s not sufficient for maintaining a proper blood sugar balance for people with type-2 diabetes. Medication with a longer-lasting form of the hormone is needed to provide an adequate release of insulin. However, GLP-1 works a little differently in monotremes. New findings in the study published Scientific Reports revealed that GLP-1 in platypus and echidnas appears to have evolved resistance to the normal degradation seen in humans and other animals. The researchers also found the hormone appears both in the gut and the venom of these animals.

The platypus produces venom during breeding season in order to ward off other males when competing for females. Because GLP-1 is an element of the venom being used by competitors, the platypus must develop resistance to the hormone in order to protect itself, as well as continue to process the hormone for its normal function in the gut. “Our analysis indeed found signatures of this tug of war between the normal function in gut and the novel function in venom,” Frank explained.

Dr Tom Grant, an expert in the ecology and biology of the platypus from the University of New South Wales who was not involved in this research, has commented on the unexpected discovery, acknowledging the potential benefits of the findings. “It obviously has possible implications for the management of human type-2 diabetes, once it has tested in animal models,” he said. “As well as this, however, the research gives us further insight into the different molecular evolution in our unique egg-laying mammals.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org , National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, David Attenborough books, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2025