DINOSAURS IN AUSTRALIA

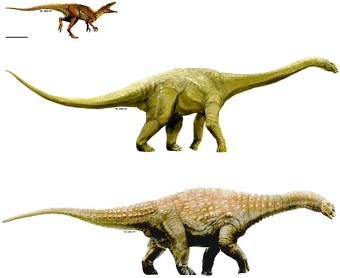

Mid Cretaceous (Latest Albian) dinosaurs from Winton Queensland Australia: Australovenator (top); Wintonotitan (middle); Diamantinasaurus (bottom)

Australia was home to a variety of dinosaurs, including ones that date before Australia separated from the Gondwana supercontinent 100 million years during the Cretaceous Period (145 million to 66 million years ago) and some when it was connected to Antarctica after that. Australia did not fully separate from Antarctica until approximately 35 million years ago, in the Eocene epoch. Australia was also home to the Eromanga Sea during the time of the dinosaurs. During the Jurassic period (201.3 to 145 million years ago), Australia was at high latitudes, with much of the continent located between 60 and 45 degrees south.

Australotitan — a brontosaurus-like sarapod — was the biggest dinosaur found in Australia. Living between 92 and 96 million years ago, it was 30 meters (100 feet) long and 6.5 meters (21.3 feet) tall. Cooper, another large sauropod, is also among the largest found in Australia. Muttaburrasaurus is a unique herbivore known only from Australia, specifically from the Winton Formation. Minmi was a small, armored herbivore, similar to an armadillo in its defense mechanism. Australovenator was a well-known megaraptora — carnivorous theropod that stood on two legs and was noted for their large hand claws. It considered Australia's most complete predatory dinosaur. Other theropod groups include southern raptors and carcharodontosaurs.

Evidence of polar dinosaurs included a shinbone fossil of unenlagiines, a type of carnivorous dinosaur related to Velociraptor that thrived in polar Australia during the Early Cretaceous. Leaellynasaura, a rare dinosaur, lived in what is now Australia when it was near the South Pole.

Many dinosaur fossils, including Australotitan and Australovenator, have been found in the Winton Formation, a layer of sedimentary rock in Queensland. Numerous dinosaur footprints have been found, including early Jurassic tracks near an Australian high school. A 200 million year old slab of rock containing over 60 dinosaur footprints was discovered. The tracks were likely left by plant-eating dinosaurs crossing a river.

See Separate Articles: ICE-AGE ANIMALS IN AUSTRALIA: WHEN, WHERE AND HOW THEY LIVED AND WENT EXTINCT ioa.factsanddetails.com ; GIANT ICE-AGE ANIMALS IN AUSTRALIA: WOMBATS, KANGAROOS AND THUNDER BIRDS ioa.factsanddetails.com

355-Million-Year-Old Footprints from Australia Reveal Earliest-Known Reptile

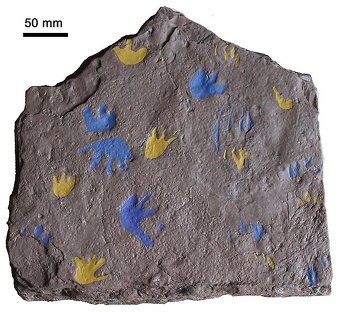

In May 2025, scientists announced that 17 footprints preserved in a slab of sandstone discovered in southeastern Australia dating to about 355 million years belonged to a reptile — rewriting the history of the evolution of land vertebrates, showing that reptiles arose much earlier than previously known. Will Dunham of Reuters wrote: The fossilized footprints, apparently made on a muddy ancient river bank, include two trackways plus one isolated print, all displaying hallmark features of reptile tracks including overall shape, toe length and associated claw marks, researchers said. They appear to have been left by a reptile with body dimensions similar to those of a lizard, they said. The footprints reveal that reptiles existed about 35 million years earlier than previously known, showing that the evolution of land vertebrates occurred more rapidly than had been thought. "So this is all quite radical stuff," said paleontologist Per Ahlberg of the University of Uppsala in Sweden, who led the study published in May 2025 in the journal Nature. [Source: Will Dunham, Reuters, May 15, 2025]

The sandstone slab from with the 355 million years old fossil reptile footprints; Footprints of front feet are shown in yellow, hind feet in blue; from Uppsala University

The story of land vertebrates started with fish leaving the water, a milestone in the evolution of life on Earth. These animals were the first tetrapods - meaning "four feet" - and they were the forerunners of today's terrestrial vertebrates: amphibians, reptiles, mammals and birds. Footprints in Poland dating to about 390 million years ago represent the oldest fossil evidence for these first tetrapods, which lived an amphibious lifestyle. These creatures were the ancestors of all later land vertebrates. Their descendants split into two major lineages - one leading to today's amphibians and the other to the amniotes, a group spanning reptiles, mammals and birds. The amniotes, the first vertebrates to lay eggs on land and thus finally break free of the water, cleaved into two lineages, one leading to reptiles and the other to mammals. Birds evolved much later from reptile ancestors.

The Australian footprints were preserved in a sandstone slab measuring about 14 inches (35 cm) across that was found on the banks of the Broken River near the town of Barjarg in the state of Victoria. The footprints each are approximately 1-1.5 inches (3-4 cm) long. They appear to have been left by three individuals of the same reptile species, with no tail drag or body drag marks. No skeletal remains were found but the footprints offer some idea of what the reptile that made them looked like. "The feet are rather lizard-like in shape, and the distance between hip and shoulder appears to have been about 17 cm (6.7 inches). Of course we don't know anything about the shape of the head, the length of the neck or the length of the tail, but if we imagine lizard-like proportions the total length could have been in the region of 60 cm to 80 cm (24 to 32 inches)," Ahlberg said. "In terms of its overall appearance, 'lizard-like' is probably the best guess, because lizards are the group of living reptiles that have retained the closest approximation to the ancestral body form," Ahlberg added.

The modest size of the earliest reptiles stands in contrast to some of their later descendants like the dinosaurs. This reptile probably was a predator because plant-eating did not appear until later in reptilian evolution. The bodies of herbivorous reptiles tend to be big and clunky, whereas this one evidently was lithe with long, slender toes, Ahlberg said.

The researchers also described newly identified fossilized reptile footprints from Poland dating to 327 million years ago that broadly resemble those from Australia. Those also are older than the previous earliest-known evidence for reptiles - skeletal fossils from Canada of a lizard-like creature named Hylonomus dating to around 320 million years ago, as well as fossil footprints from about the same time.

The reptile that left the Australian footprints lived during the Carboniferous Period, a time when global temperatures were similar to today's, with ice at Earth's poles but a warm equatorial region. Australia at the time formed part of the ancient supercontinent Gondwana and lay at the southern edge of the tropics. There were forests, partly composed of giant clubmoss trees. "The tracks were left near the water's edge of what was probably quite a large river, inhabited by a diversity of big fishes," Ahlberg said.

Carnivorous Dinosaurs in Australia 120 Million Years Ago

Jake Kotevski and Stephen Poropat wrote in The Conversation: Between 122 and 108 million years ago, the Australian landmass was much farther south than today. Victoria was positioned within the Antarctic Circle, separated from Tasmania by a vast rift valley rather than open sea. This was the Early Cretaceous, and lush forests filled with dinosaurs dominated the landscape. Most of the dinosaur fossils found in Victoria belong to small plant-eaters called ornithopods. But there are also a few theropod fossils — a diverse group that includes all known carnivorous dinosaurs, as well as modern birds.[Source: Jake Kotevski PhD Candidate, School of Biological Sciences, Monash University and PhD Candidate, Museums Victoria Research Institute, Stephen Poropat, Research Associate, School of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Curtin University. The Conversation February 19, 2025]

More than 250 theropod bones have been found in the Victorian Cretaceous. In the palaeontology collections of Museums Victoria, we have now identified five theropod fossils of particular importance. Our work on these bones has been published today in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

Research over the past decade has revealed striking similarities between Australian and South American dinosaurs. These include megaraptorids with claws shaped like scythes, and small, fleet-footed elasmarian ornithopods. There were also armoured parankylosaurians and colossal sauropods with long necks and small heads. These parallels may seem surprising at first, but both continents retained a connection to Antarctica throughout much of the Cretaceous Period. Our newly described fossils show that a bunch of different carnivorous dinosaurs seen in South America also thrived in the Cretaceous of southeastern Australia. Two shinbones provide the first evidence of carcharodontosaurs (“shark-toothed lizards”) in Australia. A third shinbone provides strong evidence for the presence of unenlagiines, a southern group of dromaeosaurs (“running lizards”). A fourth shinbone and two tail vertebrae with their chevrons, which are from a megaraptorid, represent one of Australia’s largest-known carnivorous dinosaurs.

Large predatory dinosaurs – on the scale of Tyrannosaurus – are notably absent from the Australian fossil record. Instead, Australian dinosaur populations seem to have been dominated by medium-sized carnivores called megaraptorids. Megaraptorid fossils are only known from South America and Australia. The most complete skeletons are from South America, including a relatively large one – roughly nine metres long. Carcharodontosaurs might have been the apex predators in South America, but megaraptorids ruled the roost in the land down under.

Types of Carnivorous Dinosaurs in Australia 120 Million Years Ago

Jake Kotevski and Stephen Poropat wrote in The Conversation: Carcharodontosaurs were apex predators in South America and Africa for much of the mid-Cretaceous. This group of theropods had large skulls, massive teeth and small arms. They were some of the largest predators to ever walk the Earth. Despite their success in South America and Africa, carcharodontosaur fossils had never been found in Australia – until now. With the two shinbones, we now have the first evidence of the group on this continent. Curiously, these Australian carcharodontosaurs are much smaller than their African and South American cousins, and the bones we have most closely resemble a carcharodontosaur from Thailand. [Source: Jake Kotevski PhD Candidate, School of Biological Sciences, Monash University and PhD Candidate, Museums Victoria Research Institute, Stephen Poropat, Research Associate, School of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Curtin University. The Conversation February 19, 2025]

One of the Victorian carcharodontosaur shinbones was found on the Otway Coast. The other was found on the Bass Coast, in rocks nearly 10 million years older. This demonstrates these predators were successful in this area for at least 10 million years. It’s a notable find. The large-bodied carcharodontosaurs of Africa and South America were seemingly specialised for hunting long-necked sauropods. However, this food source was likely not available to the Victorian polar carcharodontosaurs: sauropod fossils have never been found in Victoria.

Unenlagiines were lightly built (and likely feathered) predatory dinosaurs, related to Velociraptor of Jurassic Park fame. Most unenlagiine fossil remains have been found in South America. Historically, Australia had limited evidence for their presence, as well. Our description of a new unenlagiine shinbone from Victoria provides robust evidence for their success in polar Australia during the Early Cretaceous. The snouts of unenlagiines were relatively longer, and their arms relatively shorter than those of their dromaeosaur cousins from the Northern Hemisphere. This implies they had a rather different diet. The Victorian unenlagiine presumably ate fish or small land-dwelling animals. One possibility is the small mammals for which the Victorian Cretaceous is perhaps most famous – more than 50 mammal jaws have been found to date, and some are from ancient relatives of platypus and echidna.

Australia’s only reasonably complete megaraptorid is Australovenator wintonensis from Winton, central Queensland. The shinbone and tail vertebrae we describe provide evidence for a large megaraptorid in southeast Australia. Despite being almost 30 million years older than the roughly five- to six-metre-long Australovenator, the Bass Coast megaraptorid was at least 5% larger: approaching the size of its South American relatives. The large, muscular arms and fingers tipped with fearsome scythe-like claws were presumably the primary weapons of megaraptorids. In contrast to almost every other group of medium-sized carnivorous dinosaurs, megaraptorids had elongated snouts with small teeth.

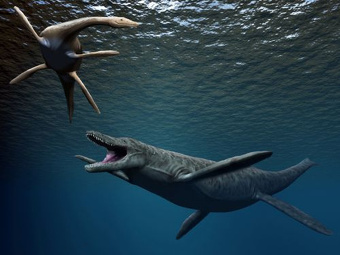

Sea Monsters That Swam in the Australian Desert 110 Million Years Ago

In the seas that covered much of Australia 110 to 98 million years ago was a predator called Kronosauraus that was 10 meters long, weighed 11 tons and had a two meter long skull with teeth the size of bananas. Kronosaurus was one of the largest known plesiosaurs (marine dinosaurs. Like all plesiosaurs, Kronosaurus had four paddle-like limbs, a short tail and, like most pliosaurids, a long head and a short neck. The largest identified skulls of Kronosaurus are much larger than those of the largest known theropod dinosaurs in size. The front of the skull is elongated into a rostrum (snout) and front ends of each side of the mandible (lower jaw) fuse and contains up to six pairs of teeth. The large cone-shaped teeth would have been used for a diet consisting of large prey. The front teeth are larger than the back teeth. The back pair of flipper-like limbs are larger than the front. The flippers would have given a wingspan of more than 5 meters (16 feet) for the largest representatives.

In 2006, scientists announced that they had identified two new species of ancient marine reptile — Umoonasaurus and Opallionectes — that swam in an Australian outback sea 115 million years ago. Reuters reported: Umoonasaurus and Opallionectes, belonged to the plesiosaurs group which included a predator like a killer whale from the Jurassic period, says palaeontologist Dr Benjamin Kear from the University of Adelaide. Kear, whose team studied 30 opalised fossils mainly from around the outback mining town of Coober Pedy in South Australia, publish their research in the journal Palaeontology and online in the journal Biology Letters. Kear says the long-necked marine reptiles swam in the shallow water of an inland sea that once existed in central Australia. Freezing polar water covered large parts of Australia 115 million years ago when the island continent was much closer to Antarctica. [Source: Reuters, July 27, 2006]

The Umoonasaurus was about 2.4 meters long and had three crest-like ridges on its skull. "Imagine a compact body with four flippers, a reasonably long neck, small head and short tail, much like a reptilian seal," Kear says. The team named the reptile after the Aboriginal name for Coober Pedy, Umoona. The Opallionectes was six meters long, with masses of needle teeth used to trap small fish and squid. Its name means 'the opal swimmer from Andamooka', the scientists say. Kear says most of the fossils found were of juvenile creatures, leading the scientists to believe they had discovered a seasonal breeding ground for the ancient reptiles.

In August 2022, a trio of amateur paleontologists, known as the “Rock Chicks” — consisting of Cynthia Prince, her sister and a friend — unearthed the first confirmed head and body of a 100 million-year-old plesiosaur known as an elasmosaur at a cattle station in western Queensland, the Queensland Museum said. [Source: Moira Ritter, Miami Herald, December 8, 2022]

In April 2025, in Alcheringa, an Australasian Journal of Paleontology. scientists at The Australian National University announced that they had examined the stomach contents of an opalized marine predator, nicknamed Eric, that died between 66 and 208 million years ago A team led by Joshua White team used X-rays and CT imagery to take a scan of the fossilized gut. They identifying gastroliths, or stomach stones, and 17 “previously undescribed fish vertebrae inside Eric’s gut,” confirming to the scientists that plesiosaurs were almost exclusively fish consumers, a statement by Australian National University said. “Eric was a mid-tier predator, sort of like a sea lion equivalent, that ate small fish and was likely preyed upon by larger, apex predators,” White said in the statement. [Source: Irene Wright, Miami Herald, Apr 25, 2023]

Minmi Paravertebra

Minmi paravertebra is one of the better known Australian dinosaurs. Alive during the Early Cretaceous period, between 125 and 110 million years ago, it was an ankylosaur — a quadrupedal dinosaur covered in bony armour — discovered in 1964 near Minmi Crossing, Queensland, and was the first ankylosaur known from the Southern Hemisphere. According to the Australian Museum Minmi had thin bony rods (ossified tendons, or 'paravertebrae') along its spine that may have been for muscle attachment. This extra muscle power along with its comparatively long legs may have made Minmi a speedy runner. A study of gut contents found that Minmi ate seeds, ferns and other soft plant material. [Source: Australian Museum]

Ankylosaurs were heavy-bodied, quadrupedal herbivores. They were armoured for protection against predators. Minmi was unique among ankylosaurs (and other dinosaurs) in having small, backwardly directed bony projections (paravertebrae, or ossified tendons) along the backbone to provide extra attachment for back muscles. These were similar to the bony structures found in crocodiles that strengthen and support the back during the 'high walk'. Along with its unusually long legs, these paravertebrae suggest that Minmi could have outrun at least some predators rather than relying solely on armour for protection. Minmi had belly armour (absent in most ankylosaurs and related stegosaurs) along with armour (scutes, spikes and dermal ossicles) over the neck and trunk. Minmi did not have a clubbed tail and, unlike almost all other ankylosaurs, had no dermal armour on the skull.

During the Early Cretaceous, part of Queensland formed a large island separate from the rest of Australia. The environment is interpreted as a mix of floodplains and woodlands. Although Minmi was found in marine sediments, it was undoubtedly washed out to sea from this nearby terrestrial environment. It is presumed Minmi was a herbivore based on analysis of other ankylosaurs. A study of preserved gut contents (cololites) in Kunbarrasaurus, a closely related species, shows that it ate the seeds and fruiting bodies of flowering plants as well as ferns and other soft-leaved plants. This is the first such study in either ankylosaurs or stegosaurs, and the best evidence yet for the diet of herbivorous dinosaurs. The plant material found in Kunbarrasaurus' abdominal region was finely diced, and it may have cut its food with its serrated cheek teeth after nipping the vegetation off with its beak. The food would then be within the mouth (possibly helped by development of fleshy cheeks).

Tracks From 21 Types of Dinosaurs Found in Western Australia

In 2017, palaeontologists said that dinosaur tracks found in ancient rocks in Westerm Australia was the the most diverse and remarkable such discovery ever, hailing them as Australia’s Jurassic Park.. An "unprecedented" 21 different types of dinosaur tracks were found found on a stretch of Australia's remote coastline, scientists said, and dated to 145 million years ago to 100 million years ago. Most of Australia's dinosaur fossils have previously come from the eastern side of the vast country. [Source: AFP, March 27, 2017]

There are thousands of tracks around a site called Walmadany. Of these, 150 could “confidently be assigned to 21 specific track types, representing four main groups of dinosaurs," Steve Salisbury, lead author of a paper on the findings published in the Memoir of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, said."There were five different types of predatory dinosaur tracks, at least six types of tracks from long-necked herbivores (eat plants or plants parts) sauropods, four types of tracks from two-legged herbivores (eat plants or plants parts) ornithopods, and six types of tracks from armoured dinosaurs." The largest dinosaur tracks ever — from a kind of sauropod — recorded were discovered there.

AFP reported: Palaeontologists from the University of Queensland and James Cook University said it was the most diverse such discovery in the world, unearthed in rocks up to 140 millions years old in the Kimberley region of Western Australia. Steve Salisbury, lead author of a paper on the findings published in the Memoir of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, said the tracks were "globally unparalleled". "It is extremely significant, forming the primary record of non-avian dinosaurs in the western half of the continent and providing the only glimpse of Australia's dinosaur fauna during the first half of the Early Cretaceous Period," he said. "It's such a magical place — Australia's own Jurassic Park, in a spectacular wilderness setting." He added: "Among the tracks is the only confirmed evidence for stegosaurs in Australia. There are also some of the largest dinosaur tracks ever recorded."

It was almost lost, with the Western Australian government in 2008 selecting the area as the preferred site for a massive liquid natural gas processing precinct. Alarmed, the region's traditional Aboriginal custodians, the Goolarabooloo people, contacted Salisbury and his team to officially research what they knew was there. They spent more than 400 hours investigating and documenting dinosaur tracks in the Walmadany area. "We needed the world to see what was at stake," Goolarabooloo official Phillip Roe said, explaining the dinosaur tracks formed part of a songline that extends along the coast and then inland, tracing the journey of a Dreamtime creator being called Marala, the Emu man.

Aboriginal Australians have developed and are bound by highly complex belief systems — known as the Dreamtime — that interconnect the land, spirituality, law, social life and care of the environment. A songline is one of the paths across the land which mark the route followed by localised "creator-beings", stories that have been handed down through the generations. "Marala was the Lawgiver. He gave country the rules we need to follow. How to behave, to keep things in balance," Roe said. The area was eventually awarded National Heritage status in 2011 and the gas project subsequently collapsed.

Australia’s Polar Dinosaurs

At a fossil site known as Flat Rocks on the South Australia coast, near the resort town of Inverloch, about two-hours southeast of Melbourne, 100 million years rocks have yielded fossils of polar dinosaurs that thrived when Australia sat about 3,200 kilometers (2,000 miles) further south than it does today and was connected to Antarctica. Scientists have also unearthed polar dinosaur fossils in Alaska and on a mountain in Antarctica. These dinosaurs thrived in environments that were cold and darkfor at least part of the year. "The moon would be out more than the sun, and it would be tough making a living," paleontologist David Weishampel of Johns Hopkins University told Smithsonian magazine.[Source: Mitch Leslie, Smithsonian magazine, December 2007]

Tom Rich, a paleontologist at Museum Victoria in Melbourne, has led excavations at Flat Rocks. Mitch Leslie wrote in Smithsonian magazine: Every year from late January to early March, Dinosaur Dreaming — the polar dinosaur project led by Rich — descends on the shore near Inverloch. Most of the dinosaur bones they find at Flat Rocks, Kool explains, come from "hypsis" (pronounced HIP-sees), short for hypsilophodonts. These small, darting plant-eaters typically stood about as tall as turkeys. Their distinctive thighbones, which sport a downward-pointing spur, are easy to recognize.

The dig in 2007 turned up some rarer finds, such as a thumbnail-size tooth from an as yet unnamed meat-eating dinosaur. One rock yielded a long, black fang that looks like an obsidian toothpick and may have come from a pterosaur, a type of flying reptile. Rich's colleague Anthony Martin of Emory University in Atlanta announced that patterns in a 115-million-year-old layer of mud at Flat Rocks are dinosaur tracks. The 14-inch-long, three-toed footprints came from a type of meat-eating dinosaur called a theropod. Judging from the size and spacing of the prints, it must have stood about 12 feet high, making it the largest carnivorous dinosaur known to have lived there.

Dinosaurs also thrived farther south. Antarctica hasn't moved much in the past 100 million years, stalling over the South Pole. Today, well-insulated animals and stubbly plants can survive the continent's brutal cold, at least close to the coast. But fossilized leaves and other plant remains suggest that during the dinosaurs' day Antarctica had a temperate climate. Judd Case of Eastern Washington University in Cheney says that Antarctic dinosaurs from the late Cretaceous period around 70 million years ago resembled those that lived in other parts of the world some 60 million years earlier. Case says this suggests that some kinds of dinosaurs hung on in Antarctica long after they had died out elsewhere. Perhaps Antarctica was an oasis for them as flowering plants spread across the rest of the world and outcompeted the pine tree relatives that

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see “The Strange Lives of Polar Dinosaurs” by Mitch Leslie, Smithsonian magazine, December 2007 smithsonianmag.com

How Australia’s Polar Dinosaurs Survived

Mitch Leslie wrote in Smithsonian magazine: At the time dinosaurs arose, around 220 million years ago, the earth's continents were fused into a single supercontinent we now call Pangea. It began breaking up around 200 million years ago, and Australia and Antarctica, which were still stuck together, stayed near the South Pole. When the fossilized creatures Rich studies were scurrying around, about 100 million years ago, southern Australia sat close to the bottom of the planet, and was just starting to pull away from Antarctica. (Australia's current position reflects that it has been inching northward "at the rate your fingernails grow," Rich says.) [Source: Mitch Leslie, Smithsonian magazine, December 2007]

During the animals' heyday in the early Cretaceous period, the sun didn't rise in southern Australia for one and a half to four and a half months every year. At the North and South poles, the gloom lasted for six months. Plant growth in these areas would have periodically slowed or stopped, potentially creating a food crisis for any dinosaurs that lived there. In more than 20 years of digging, Rich and his colleagues have found the remains of at least 15 species. For example, the knee-high hypsi Leaellynasaura amicagraphica (named for Rich's daughter, Leaellyn) once dodged predators at what is now Dinosaur Cove. Rich's son, Tim, got his name attached to another Dinosaur Cove denizen, the six-foot-tall Timimus hermani, which probably looked and ran like an ostrich.

Dinosaurs had two choices when winter arrived — tough it out or try to escape. The question of how dinosaurs survived the polar cold has gotten entangled with the broader question of whether the ancient beasts were warmblooded (endothermic), like modern birds and mammals, or coldblooded (ectothermic), like modern reptiles. In a cold environment, endotherms keep their bodies warm enough for muscles to flex and nerves to fire by generating heat through their metabolism. Ectotherms, by contrast, warm their bodies by absorbing heat from their surroundings — think of a lizard basking on a rock. Endothermy isn't necessarily better, notes David Fastovsky of the University of Rhode Island. Endotherms have the edge in stamina, but ectotherms need much less food.

The prize discovery from Rich's Dinosaur Cove excavation suggests that Leaellynasaura stayed active during the long polar winters. A two-inch-long Leaellynasaura skull the color of milk chocolate is the closest to a complete dinosaur skull the team has found. The base remains partly embedded in a disk of gray rock scored by numerous grooves where Kool meticulously exposed the fossil with a fine needle. Enough of the bone is visible for Rich to analyze the size of the eye sockets. Hypsis generally had big eyes, but Leaellynasaura's are disproportionately large — perhaps so they could capture more light during the protracted murk of polar winters. Moreover, the back of the same skull has broken off to expose a mold of the brain, known as an endocast. Rich found that the dinosaur had bulging optic lobes, parts of the brain that process visual information. Leaellynasaura's optic lobes are larger than those from hypsis that lived in non-polar environments, suggesting that it had extra brainpower to analyze input from its big eyes. Other dinosaurs might have migrated north, if they lived in the Southern Hemisphere. Rich says his dinosaurs would have made unlikely travelers. They were small, and an inland sea would have blocked their path to warmer climes.

Opalized Fossils

Some fossils in Australia in the Coober Pedy area of South Australia — the world’s premier opal-producing region — and Lightning Ridge, New South Wales undergo a rare process called opalization. This phenomenon, almost exclusively observed in Australia, turns bones that are preserved in silica into opals, a kind of gemstone. The opal matrix can preserve intricate details of the original organism, making them visually stunning and scientifically significant.

In opalized fossils the original organic material (like bone, shell, or wood) has been replaced by opal, a mineraloid composed of hydrated silica. This process typically occurs when silica-rich water fills cavities left by decaying organic matter, eventually hardening into opal. Opal forms from silica (silicon dioxide) dissolved in water. This silica-rich water infiltrates cracks and voids in the rock, often created by decaying organic matter like bones or shells. As the water evaporates, it leaves behind a deposit of silica, which hardens into opal. If the silica fills a cavity left by a decayed organism, it can create a detailed opalized cast or impression of the original object.

Opalized mollusc shells have been found in Coober Pedy. Opalized teeth from various creatures are found in Lightning Ridge. Boulder opal fields produce opalized wood and vegetation. Fossils of other marine animals, like reptiles, have also been found in opal fields. Belemnites: are fossilized squid, which sometimes some have been found opalized. Opalized fossils are relatively rare, making them highly sought after by collectors and researchers.

Discovering an Opalized Dinosaur Jawbone

The opal trader Mike Poben was one of the first people to realize the significance of opalized fossils. In 2013, a pair of miners turned up at his door offering him some rough opal. ABC reported: Mike bought a few bags of these, known as "skin shells": ancient sea shells that have turned into opal. The first bag was mostly junk. But inside the second bag, Mike found a small fragment, about as big as the joint of his middle finger. When he turned it over, he saw two small fan-shaped ridges and a vein of blue-green opal. As he looked at the piece through his magnifying glass, the hair started rising on the back of his neck. "I think I was shocked, first of all … something in the back of my head said tooth," he said. "And then something else said, 'If these are teeth, then this is a jawbone.' "Opalised jawbone with teeth are rare as rocking horse shit … you just don't find them." [Source: Michael Dulaney and Elizabeth Kulas for Days Like These, ABC, November 20, 2020]

A geological quirk means some of the richest veins of the most valuable opals in the world — black opals — are found around Coober Pedy, in South Australia, and Lightning Ridge. The modern Gulf of Carpentaria is the last remnant of a shallow inland sea that once covered most of eastern Australia about 100 million years ago. Back then, the Australian continent sat 60 degrees south of where it is today, and Lightning Ridge was almost coastal real estate. The dry and dusty region of today was once within the catchment of rivers and lagoons that drained into this sea, and the area would have been covered with densely vegetated, lush forests. Millions of years later, what these great ancient seas have left behind is a strange sort of aquatic spirit in Coober Pedy and Lightning Ridge.

After a few year Mike contacted and met with Phil Bell, a paleontologist, and his Italian colleague, Federico Fanti. Dr Bell knew right away that these opals, flashing with blues and pinks, were unique. "It was still kind of dirty [and] still had a lot of rock adhering to the surface of it," he recalled. "I saw not only the beautiful color in these two pieces of bone, but also the teeth. And it was obvious we were looking at the jawbone of a dinosaur."

From there, Dr Bell began scouring museums around the world, comparing the jawbone to other fossil records, hoping to find a match. After two years a match was found. "It's a new species. They have proved beyond scientific doubt that it's a previously undiscovered animal — a new Australian dinosaur." The species that furnished Mike with the opalised jawbone were dog-sized herbivores, probably between one meter and two meters in length. They likely travelled in herds, picking at the low branches and eating plants that grew around the freshwater lagoons of the region. Some of the species had a kind of beak on the lower jaw. They now also have a full scientific name, inspired by Mike: Weewarrasaurus pobeni.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org , National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, David Attenborough books, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2025