Home | Category: Animals / Marsupials

WOMBATS

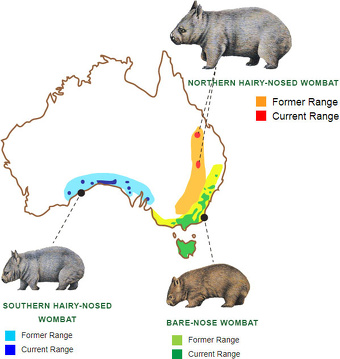

wombat species: 1) Common Wombat (Vombatus ursinus), 2) Southern Hairy-nosed Wombat (Lasiorhinus latifrons), 3) Northern Hairy-nosed Wombat (Lasiorhinus krefftii)

Wombats (Vombatidae) are one of Australia's cutest and most endearing animals. A relative of the koala, these furry marsupial looks sort of like a chubby groundhog with a big head, According to “The Australians Alphabet” from 1905:

“W stands for Wombat

Its true, but it’s droll.

When he's not up on top

He's down in a hole”.

Wombats are muscular, have short-legged and move around on all four limbs. Members of the family Vombatidae, they live in southern and eastern Australia, including Tasmania, as well as an isolated patch of about 300 hectares (740 acres) in Epping Forest National Park in central Queensland. Living species are about one meter (40 inches) in length, including their small, stubby tails, and weigh between 20 and 35 kilograms (44 and 77 pounds). They are adaptable and habitat tolerant, and are found in forested, mountainous, and heathland areas. [Source: Wikipedia +]

A group of wombats is known as a wisdom, mob, or colony.Koalas and wombats are each other's closest relatives. Among the characteristics they share are a backward-facing pouch, vestigial tail, presence of a peculiar glandular patch in the stomach, formation of a placenta, loss of some premolars, and details of their musculature. A close relationship has also been suggested by DNA studies. [Source: Phil Myers, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Vombatidae, the wombat family, contains two genera and three species.

Common wombats (Vombatus ursinus), also known as the bare-nosed wombats, with three subspecies: a) Vombatus ursinus hirsutus, found on the Australian mainland; b) Vombatus ursinus tasmaniensis, found in Tasmania; and c) Vombatus ursinus ursinus, found on Flinders Island in the Bass Strait and Maria Island in the Tasman Sea.

Northern hairy-nosed wombats, or yaminon (Lasiorhinus krefftii), which are critically endangered

Southern hairy-nosed wombats (Lasiorhinus latifrons), the smallest of the three species +

Fatso the wombat was the most popular soft toy of the 2000 Summer Olympics in Sydney. It is said wombats make good pets, love to be picked up and will do about anything for a good scratch. On a visit by the royal family to Australia a wombat became enamored with Queen Elizabeth and crawled over her while she was trying to give a speech. But there are also reports and wombats attacking and injuring people. Also on the negative side, many wombats, especially those looking for new territories, are killed by automobiles. Others have suffered due too loss of habitat, development, predation and competition from livestock and introduced animals. H. Gordon's experiments in 1985 showed a positive correlation between numbers of wombats and kangaroos in areas of grassland, but a negative correlation between numbers of wombat and cattle.

Book: “The Wombat” by Barbara Toggs, New South Wakes University Press, 1988

RELATED ARTICLES:

WOMBAT SPECIES: COMMON (BARE-NOSED) AND HAIRY-NOSED ONES ioa.factsanddetails.com

NORTHERN HAIRY-NOSED WOMBATS: ENDANGERED, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION, COMING BACK ioa.factsanddetails.com

MARSUPIALS: HISTORY, EVOLUTION, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

MARSUPIALS IN AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

ICE-AGE ANIMALS IN AUSTRALIA: WHEN, WHERE AND HOW THEY LIVED AND WENT EXTINCT ioa.factsanddetails.com

GIANT ICE-AGE ANIMALS IN AUSTRALIA: WOMBATS, KANGAROOS AND THUNDER BIRDS ioa.factsanddetails.com

Wombat History

Around 30,000 years ago, large wombats grazed across Australia. As the Australian climate dried out, they evolved into smaller, burrowing animals. Aboriginals hunted wombats for meat and skin. European settlers regarded them as pests and killed them because they ate crops and burrowed under and undermined fences that separated livestock from rabbits and dingoes. The hunting of wombats was encouraged until fairly recently. Now wombats are protected. [Source: Perry Barboza, Natural History, December 1995]

Depictions of wombats in Aboriginal rock art are rare, though examples estimated to be up to 4,000 years old have been discovered in Wollemi National Park. Wombat were depicted in aboriginal Dreamtime as an animal of little worth. The mainland stories tell of the wombat as originating from a person named Warreen whose head had been flattened by a stone and tail amputated as punishment for selfishness.

The name "wombat" comes from the now nearly extinct Dharug language spoken by the aboriginal Dharug people, who originally inhabited the Sydney area. The name It was first recorded in January 1798, when John Price and James Wilson, Europeans who had adopted aboriginal ways, visited the area of what is now Bargo, New South Wales.

Price wrote: "We saw several sorts of dung of different animals, one of which Wilson called a 'Whom-batt', which is an animal about 20 inches [51 centimeters] high, with short legs and a thick body with a large head, round ears, and very small eyes; is very fat, and has much the appearance of a badger."

Wombats were often called badgers by early settlers because of their size and habits. Because of this, localities such as Badger Creek, Victoria, and Badger Corner, Tasmania, were named after the wombat. The spelling went through many variants over the years, including "wambat", "whombat", "womat", "wombach", and "womback", possibly reflecting dialectal differences in the Darug language.

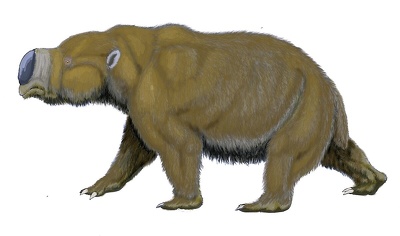

Diprotodons — Rhinoceros-Sized Mega-Wombats

During the Pleistocene Period (2.6 million to 11,700 years ago), herds of giant wombats the size of a rhinoceros roamed the plains of southern Australia. These mega-wombats were called Diprotodons. Diprotodons were the largest marsupials ever to roam the earth, weighing up to 2.8 tonnes and living between two million and 50,000 years ago and dying out around the time indigenous tribes first appeared. A relative of the modern-day wombat, these herbivores were just one of many of megafauna to roam ancient Australia. Megafauna are thought to have evolved to such large sizes to cope with inhospitable climates and food scarcity,

In 2012, Australian scientists said they had found the biggest-ever graveyard of diprotodons in remote fossil deposit in the Queensland outback. The site contains up to 50 diprotodon skeletons including a huge specimen named Kenny, whose jawbone alone is 70 centimeters (28 inches) long. Lead scientist on the dig, Scott Hocknull from the Queensland Museum in Brisbane, said Kenny was one of the largest diprotodons he had ever seen and one of the best preserved specimens. "When we did the initial survey I was just completely blown away by the concentrations of these fragments," he told AFP by telephone from the far-flung desert dig site, which he estimated at between 100,000-200,000 years old. [Source: Amy Coopes, AFP, June 21, 2012]

Hocknull likened diprotodon to "a cross between a wombat and a bear but the size of a rhinoceros". They were Pigeon-toed and with a backward-facing pouch large enough to carry an adult human, The mega-wombats in the mass graveyard appeared to have been trapped in boggy conditions at the site after seeking refuge there from extremely dry conditions during a period of significant climate change in ancient Australia,

See Separate Articles: ICE-AGE ANIMALS IN AUSTRALIA: WHEN, WHERE AND HOW THEY LIVED AND WENT EXTINCT ioa.factsanddetails.com ; GIANT ICE-AGE ANIMALS IN AUSTRALIA: WOMBATS, KANGAROOS AND THUNDER BIRDS ioa.factsanddetails.com

Wombat Characteristics

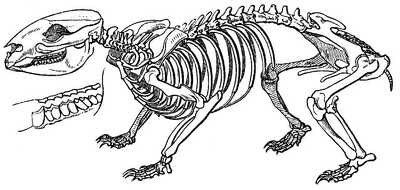

Wombats are medium to large size marsupials, weighing between 19 and 39 kilograms (41.8 to 85.8 pounds). All three species are about one meter (3.3 feet) in length and stand about 30 to 35 centimeters (12 to 14 inches) at the shoulder. They have a stocky body, short, stumpy limbs, small ears, and a very short tail. Their broad head is compactly built and adapted for constructing burrows. The limbs, also used in burrowing, are especially powerful, with short broad feet and strong, flat claws. They have a plantigrade posture (walking on the soles of the feet, like a human or a bear).[Source: Phil Myers, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Wombat fur varies in color from a sandy to brown, or from grey to black. They typically live up to 15 years in the wild, but can live past 20 and even 30 years in captivity.The longest-lived captive wombat lived to 34 years of age, making it at least one of the longest-lived marsupials ever. For a long time, according to to the Guiness Book of World Records, the longest lived marsupial every reliably recorded was a 26½ year old wombat that died at the London Zoo in 1906. In 2020, biologists discovered that wombats, like many other Australian marsupials, display bio-fluorescence under ultraviolet light.

Wombats have large brains for animals their size and are very muscular and strong. They are well adapted to a subterranean lifestyle. Their mass is concentrated in their cylindrical. muscular torso. Their stubby legs and broad feet are good for both digging and squeezing into tunnels. Large wombats can reach a weight of around 45 kilograms (100 pounds), which is about as large as a burrowing animals gets. If they were any larger there would be a risk of the tunnels they dig collapsing on them. [Source: Perry Barboza, Natural History, December 1995]

Like kangaroos. wombats have a pouch on their belly side. The only difference is that the wombat poach, like that of koalas, opens towards the rear rather than towards the head. The pouch of wombats is well developed. The embryo forms a allantoic placenta, as is true of at least some peramelids and koalas but not other marsupials. One advantage with a backward-facing pouch is that when digging, the wombat does not gather soil in its pouch over its young.

Wombats have a remarkably rodent-like skull. They have a single pair of sharp incisor teeth and are not shy about using them. All wombat teeth lack roots and are ever-growing, like the incisors of rodents.[ According to Animal Diversity Web: These teeth are heavily built and rodent-like in form. Also like the incisors of rodents, the incisors of wombats have enamel on anterior and lateral surfaces only. The incisors are followed by a large diastema. The cheek teeth are hypsodont and unrooted. The molars are relatively simple; their surfaces contain two major lophs ( bilophodont). The dental formula is 1/1, 0,0, 1/1, 4/4 = 24. On the skull itself, the coronoid process of dentary reduced and the masseter is the primary muscle used in mastication. Wombats have a strongly built zygomatic arch and short rostrum (hard, beak-like structures projecting out from the head or mouth). |=|

Australian scientists have found that wombats glow under ultraviolet light. University of Kansas biologist Leo Smith, an expert in biofluorescence, told NPR it was not clear what purpose the trait served in mammals. “It’s not something that you can necessarily come up with a really good explanation for why it might be there or what could be the advantage. Like a lot of things just evolve and they’re not good or bad, they’re just whatever,” Smith said. [Source: Josephine Harvey·Reporter, Huffington Post, December 15, 2020]

Wombat Feeding Behavior and Digestion

Wombats are strictly herbivores (eat plants or plants parts) and grazers (primarily eat grass or other low-growing plants). Their diets consist mostly of grasses, sedges, herbs, bark, and roots. Their rodent-like incisor teeth are adapted for gnawing tough vegetation. Like many other herbivorous mammals, they have a large diastema between their incisors and the cheek teeth, which are relatively simple. Although their diet is fibrous, tooth wear is not an issue for wombats, as their teeth continue to grow throughout their life. This means even a very old wombat still has a full set of teeth and can grind its food very finely to extract as much nutrients as possible.

Wombats are mainly grazers that feed primarily at night. Before livestock was introduced by Europeans around 200 years ago, wombats and kangaroos were the primary grazing animals in Australia. In the relatively wet springs of southeastern Australia, wombats feed on tender shoots of green grass. which is high in protein and low in fiber. This changes as the weather dries and the grass turns brown and loses its protein. Wombats are vulnerable to drought and lack of pastures, Unlike kangaroos which cover a large area, wombats are tied to a fairly small territory and stay close to their burrows which requires a lot of effort to build. [Source: Perry Barboza, Natural History, December 1995]

Wombats have a simple stomach and a short, broad cecum (a pouch connected to the junction of the small and large intestines), where much of digestion takes place. They digest their food in a manner similar to grazing ruminant animals such as cows and sheep. They ground up their food well, releasing starches and proteins. The fiberous material is digested with help of microbes that break down the cellulose through fermentation in the wombat's cecum and hindgut, the largest part of the animals digestive system. [Source: Perry Barboza, Natural History, December 1995]

A wombats digestive system is more efficient than cattle or kangaroos. The fermentation process in wombats begins soon after the food is swallowed and much of the nutrition is lost to the bacteria. Wombats recycle waste nitrogen and are able to reuse 42 percent of the nitrogen from their urea. Wombats have a very slow metabolic rate. They need only 32 percent as much food per bodyweight as kangaroos and 25 percent as much as sheep. Because they spend almost all of time in their burrows and come out at night, when temperatures are the same as their burrows, the use little energy maintaining their body temperature. This allows the wombats to survive when food is scarce such as in a drought.

Mystery of Wombat’s Cube-Shaped Poop

Wombats produce distinctive cubic feces and arrange them on rocks and logs to mark territories and attract mates, It is thought the cubic shape makes them more stackable and less likely to roll. The method by which wombats produces their fecal cubes is not well understood, but it is believed to involve, the wombat intestine which stretches preferentially at the walls, with two flexible and two stiff areas around the intestine. Adult wombats produces between 80 and 100, two centimeters (0.8 in) pieces of feces in a single night, and four to eight pieces each bowel movement. In 2019 the production of cube-shaped wombat feces was the subject of the Ig Nobel Prize for Physics, won by Patricia Yang and David Hu. [Source: Wikipedia]

A study published in January 2021 in Soft Matter revealed how the intestines bare-nosed wombats (Vombatus ursinus) constricted to create poop cubes. [Source: Elizabeth Gamillo, wrote in Smithsonianmag.com “In 2018, study co-author Patricia Yang, a mechanical engineer at Georgia Institute of Technology, and her team previously found that the cube-shaped poop formed at the end of the wombat’s digestive process and that the wombat’s intestinal wall contained elastic-like properties.

“To build on those results and fully understand how the wombat’s soft intestinal walls created sharp cube-like edges in the poop, Yang and her team dissected two wombats and examined the texture and structure of the intestinal tissue. A 2-D mathematical model created from the wombat’s intestinal tract showed how the organ expanded and contracted during digestion — and eventually squeezed out the excrement. “A cross-section of the wombat’s intestine is like a rubber band with two ends kept slightly taut and the center section drooping. The rigid and elastic parts contract at different speeds, which creates the cube shape and corners,” Yang told Slate. [Source: Elizabeth Gamillo, Smithsonianmag.com, February 8, 2021]

The wombat's 10-meter (33-foot) -long intestines are ten times the size of the wombat itself. Digestion take around 8 to 14 days to complete — four times longer than a human. Wombat digestion aids their survival in arid conditions and it produces drier feces because all nutrients and water have been extracted and put to use in the body. After removing all nutritional content from food, contractions in the intestine shape the poop into a cube. “The contractions are very subtle, and these corners get more and more accentuated over 40,000 contractions that the feces experiences as it travels down the intestine,” David Hu, a professor of fluid mechanics at the Georgia Institute of Technology and co-author of the study, told Gizmodo. “Hu says that their findings could also help raise wombats in captivity because their feces’ shape is a tell-tale sign of health. “Sometimes [captive wombats’] feces aren’t as cubic as the wild ones,” Hu told Science.

Wombat Behavior

Wombats are fossorial (engaged in a burrowing life-style or behavior, and good at digging or burrowing), nocturnal (active at night), crepuscular (active at dawn and dusk), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), sedentary (remain in the same area), territorial (defend an area within the home range), and have dominance hierarchies (ranking systems or pecking orders among members of a long-term social group, where dominance status affects access to resources or mates). |=|

Little is known about the behavior of wombats. They are shy creatures and tend to be antisocial. They spend all day in their burrows, coming out at night to graze on grass. They forage early in the evening during the austral winter and late at night in the summer. They only time they seek the company of other wombats is during the mating season. Although mainly crepuscular and nocturnal, wombats may also venture out to feed on cool or overcast days. They are not commonly seen, but leave ample evidence of their passage, treating fences as minor inconveniences to be gone through or under.

Wombats are generally placid and easily tamed. They like to sleep on their backs with their legs sprawled. When at rest their breathing is so light some people have mistaken them dead. Wombats have an extraordinarily slow metabolism. They generally move slowly but can run short distances at speeds of up to 40 kilometers per hour (25 miles per hour) and jump over one-meter-high fences. When wombats walk, their behinds sway from side to side. This feature, along with their large heads and habits, such as curling up to rest on their sides or sitting on their haunches with their forepaws folded in front, make wombats appear slow and clumsy.

Wombats are generally quiet animals. Bare-nosed wombats can make a number of different sounds, more than hairy-nosed wombats. Wombats tend to be more vocal during mating season. When angered, they can make hissing sounds. Their call sounds somewhat like a pig's squeal. They can also make grunting noises, a low growl, a hoarse cough, and a clicking noise.

Wombat Burrows and Home Territories

Wombats are burrowers. They build impressive burrow systems with many burrows. Some burrows are tens of meters in length. Wombat have powerful front legs, ideal for digging, and equally strong rear legs that push dirt out the way. Even their pouch design is an adaption as it faces backwards so dirt doesn;t get into while the wombat is digging. [Source: Perry Barboza, Natural History, December 1995]

Wombat burrows are large and conspicuous. Wombats spend a great deal of energy making their burrow. Large burrows may have burrows that extend more than 30 meters (100 feet) and descend two meters (six feet) underground and house more than one wombat. Wombats often live near streams or similar bodies of water due to their preference of building burrows above creeks and streams. Due to their grazing and soil-displacing habits, wombats may help to provide different microsites that influence vegetative growth patterns in these environments. [Source: Benjamin Galetka, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Multiple wombats might use the same burrow, but rarely at the same time. When burrowing, they remove dirt in front of them using the claws, then "bulldoze" the dirt backwards using their rump. They use a similar tactic for dealing with predators in their burrow, backing up at the attacker. Wombats may have multiple resting chambers, in which they build nests out of grass, leaves and sticks. To conserve energy, they may spend up to 16 hours a day sleeping in these chambers. [Source: Benjamin Galetka, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Wombats defend home territories centered on their burrows, and they react aggressively to intruders. The common wombat occupies a range of up to 23 hectares (57 acres), while the hairy-nosed species have much smaller ranges, of no more than four hectares ha (10 acres). When attacked, wombats dive into a nearby burrow, using their rumps to block a pursuing attacker. According to an urban legend, wombats sometimes allow an intruder to force its head over the wombat's back, and then use its powerful legs to crush the skull of the predator against the roof of the tunnel. However, there is no evidence to support this.

Wombat Defenses Fighting Behavior and Attacks

Wombats are vulnerable to attacks from dogs and dingoes when they are above ground at night. Tasmanian devils prey on wombats. But wombats can put up a good fight and their bodies and burrows provide good defenses. The rear of a wombat's body is very tough, with most of the posterior made of cartilage. This, combined with its lack of a meaningful tail, makes it difficult for any predator that follows the wombat into its burrow to bite and injure the wombat.

Don't let the cutsiness of wombat fool you. When cornered by dogs they can be quite ferocious and powerful. Barboza wrote: "Below ground they are invincible...Within the confines of its burrow, the wombat uses its bony lower back as a shield. Shoving backward with its powerful hind legs, the animal can block attackers (including other wombats. There have been unsubstantiated reports of wombats crushed invading dogs to death by pressing them against the roofs of their of burrows or smothering them at the end of a blind tunnel.

Humans attacked by wombats can receive bite marks and puncture wounds from wombat claws. Startled wombats can charge humans and knock them over, resulting in broken bones from the fall. One even knocked a scientist unconscious while he tried to pull it across a road. One naturalist, Harry Frauca, once received a bite 2 centimeters (0.8 in) deep into the flesh of his leg — through a rubber boot, trousers and thick woollen socks. The Independent, reported that on April 6, 2010, that a 59-year-old man from rural Victoria state was mauled by a wombat (thought to have been angered by mange causing a number of cuts and bite marks requiring hospital treatment. The man killed the wombat with an axe. [Source: Wikipedia]

Wombat Reproduction and Young

Wombats appear to be polygynous (males have more than one female as a mate at one time). Males have penile spines, a non-pendulous scrotum, and three pairs of bulbourethral glands. The testes, prostate, and bulbourethral glands enlarge during the breeding season. The mating rituals of common wombats includes the male chasing the female in circles for several minutes at a time until the female slows down enough for him to catch up. At this point he bites her rump, grasps her with his forelegs, and flips her onto her side. The male then mounts her while laying on his side; after which the female may break off into a jog, and the chasing behavior ensues again. These sessions may last about 30 minutes.

Female wombats give birth to a single young after a gestation period of roughly 20–30 days, which varies between species. Parental care is provided by females. Young are altricial, meaning they are relatively underdeveloped at birth, and about the size of a jelly bean when born. All species have well-developed pouches, which the young leave after about six to seven months. Wombats are weaned after 15 months, and are sexually mature at 18 months.

Young wombats can be very rambunctious. Describing a wombat at play, Perry Barboza wrote in Natural History magazine, "A young wombat eager to play charges into another juvenile, often butting with its head or biting, and then runs away to solicit a chase. While running the wombat may indulge in shoulder rolls and somersaults." [Source:Perry Barboza, Natural History, December 1995]

Wombat Mange — A Nasty Disease

Sarcoptic mange is a skin infection in mammals caused by skin-burrowing parasites mite, Sarcoptes scabiei, which causes hair loss and may lead to a slow, painful death. University of Tasmania wildlife ecologist Scott Carver told ABC it was the most severe disease he had seen in animals. "Wombats lose hair, they become irritated, they are not able to sleep properly and, ultimately, they are fighting a losing battle," he said. [Source: Rhiannon Shine, ABC, July 15, 2018]

In the mid 2010s, at least half the wombats in Narawntapu National Park in Tasmania's north had mange and a campaign was launched to help them. Kellie Simpson has spent 125 hours watching wombats in the park and has collected the most comprehensive data yet on their behavior. She said mange affected the wombats' behavior and left them with poorer body condition. "Wombats with mange spent less time walking, they spent more time drinking water, they had a slower feeding rate," she said. [Source: Selina Bryan, ABC, January 11, 2015]

.

Sarcoptic mange affects more than 100 mammalian species worldwide, including humans and dogs. The disease is referred to as scabies in humans and mange in other species. Australian native mammals that are known to be affected by mange include ringtail possums, brown bandicoots, koalas and common wombats. Mange infection in an animal can result in aggressive scratching, hair loss, skin thickening and crusting, skin discoloration, open wounds (from scratching), weight loss, and in severe cases, death (as a result of secondary infection and suppressed immune system). [Source: Department of Natural Resources and Environment Tasmania nre.tas.gov.au ]

It is thought that humans were the original host of sarcoptic mites, who then passed it on to their domestic animals, with subsequent spill-over events to wildlife. Current evidence strongly indicates that mange was introduced to Australia (and Tasmania) by Europeans and their domestic animals about 200 years ago. The current distribution of mange disease is considered worldwide.

Of the native Australian mammal species known to be affected by mange, wombats appear to be most impacted. Wombat burrows are believed to have good conditions for the survival of mites and the transfer of mites between wombats. Laboratory studies have shown that cool, humid conditions lead to the longest survival of mites away from their host — such conditions can occur in wombat burrows.

Wombat populations throughout south-eastern Australia are affected by mange. In Tasmania, mange has been reported from northern, eastern, central and southern areas of Tasmania, including Flinders Island. No confirmed observations of mange have been recorded from western Tasmania nor on Maria Island. The disease generally occurs at low prevalence, but more extreme outbreaks can occur within populations. It is not known why these outbreaks occur, but they appear to be associated with times of nutritional stress and/or overcrowding (i.e. high-density wombat populations).

Combating and Treating Wombat Mange

There is no method to eradicate mange from the wild, however individual wombats and other animals can be treated for mange. While treatment may be relatively straightforward for tame or captive animals, it is more challenging to treat animals in the wild, especially for wombats which are typically nocturnal, live underground and are not well-suited to captivity. Preliminary results from recent treatment trials of new drugs are promising and further research is underway to determine the best and safest way to treat wombats in the wild. Whilst treatment methods will help combat mange outbreaks and treat individual animals, it will not eliminate mange from wild populations. [Source: Department of Natural Resources and Environment Tasmania nre.tas.gov.au ]

To treat the animals, researchers have installed flaps at the entrance to burrows that applies medication. As a wombat passes through the flap the treatment is poured on its back. The current treatment of mange in Wombats requires regular doses of moxidectin (Cydectin) using the method of burrow flaps or pole and scoop. The number and recurrance of treatment depends on the dosage amount (high or low dose).

Recommended treatment methods are delivery of the acaricides (pesticides that kill mites and ticks) via a burrow flap over a wombat burrow that doses the wombat as it enters and exits the burrow, or by direct application straight onto the wombat via a scoop on a pole. The pole and scoop method is generally used for badly affected wombats that can be easily approached. Wombats should not be chased to apply treatment.

Two studies of the effectiveness of treating mange in common wombats using the burrow flap method have been conducted in the wild, one in Tasmania and one in NSW. Results indicate that the effectiveness of the treatment regime is variable at the population level. Both studies highlighted the considerable logistical challenges in treating all individuals and all burrows.

Multiple doses of Cydectin are required, as the drug isn’t easily absorbed through affected skin and therapeutic drug levels need to be maintained for long enough for the skin condition to improve and the animal to resist re-infection from the environment.

A new treatment method, using Fluralaner (Bravecto) has now been approved for use on wombats by the Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority. Treatment involves a spot-on dose that is applied to the back of the wombat using a pipette. Persons who are trained and experienced in the use of veterinary chemicals, who have appropriate experience in identifying mange infection and fluralaner toxicity signs in wombats may use this product . Permits may also be required from NRE Tas depending on the method of treatment administration.

Reinfection of treated wombats can occur if infected wombats remain in the population, if other hosts transmit mites to wombats, or if mites remain viable and infectious in the landscape. Due to the potential for the mites to develop resistance to the acaricides continuous treatment is not encouraged.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org , National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, David Attenborough books, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2025