INTRODUCED ANIMALS IN AUSTRALIA

Australia has had very severe problems with animals like cane toads, rabbits, cats, camels, foxes and pigs that were introduced from outside Australia and multiplied to out of control numbers.

Some animals such as sparrows, trout, and salmon were introduced in the mid-1800s by societies that wanted Australia to be more like Britain or Europe.

Terms used describe these introduced plants and animals including include invasive and alien. Many are thriving at the expense of indigenous types. Invading species have helped wipe about a dozen native mammals, among them the desert bandicoot, Alice Springs mouse, and central hare wallaby. Corey J. A. Bradshaw and Andrew Hoskins wrote in The Conversation: Shamefully, Australia has one of the highest extinction rates in the world. And the number one threat to our species is invasive or “alien” plants and animals. Invasive species are those not native to a particular ecosystem. They are introduced either by accident or on purpose and become pests. [Source: Corey J. A. Bradshaw, Flinders University; Andrew Hoskins, CSIRO, The Conversation July 29, 2021]

Various kinds of invasive mollusks of and seaweed were introduced on the ballast water of ships. When released they drove out local species. The proliferation of rabbits resulted in a menace to sheep, and in 1907, a thousand-mile-long fence was built to keep rabbits out of Western Australia. Subsequently, a similar fence was erected in the east to prevent the incursion of dingoes. [Source: “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations”, 2007]

Introduced non-native species are called "ferals" in Australia.Ilsa Sharp wrote in “CultureShock! Australia”: Feral animals — in other words, humankind’s animals left to go wild in the bush and desert — are some of the great banes of the Australian ecology and a constant reminder of the ignorance of the early white settlers. There are feral rabbits, feral birds too, such as mynahs and starlings, and perhaps most startling of all, dogs and cats. If you are a newcomer, do not approach ‘pussycats’ seen in the countryside with the same affectionate trust you might offer your best friend’s pet cat. It could turn out to be a snarling tiger-like thing if it is a ‘feral’. [Source: Ilsa Sharp, “CultureShock! A Survival Guide to Customs and Etiquette: Australia”, Marshall Cavendish, 2009]

By the way, as an aside, you will frequently hear the word ‘feral’ used in a different context in Australia: it is a derogatory term used to dismiss contemptuously all somewhat left-wing, ‘hippie’, unconventional people, such as ‘greenies’, who protest against things or live alternative lifestyles. Often the implication of this use of ‘feral’ is that the person referred to is not only wild and out of control but also dirty, unwashed, unemployed and on welfare).

RELATED ARTICLES:

CATS (AUSTRALIA’S MOST DESTRUCTIVE INVASIVE SPECIES), ENDANGERED ANIMALS, CONTROL AND ERADICATION: ioa.factsanddetails.com

LARGE FERAL ANIMALS IN AUSTRALIA — CAMELS, PIGS, WATER BUFFALO, HORSES — DAMAGE, CONTROL AND CULLS ioa.factsanddetails.com

ANIMALS IN AUSTRALIA: TYPES, UNIQUENESS, HABITATS, CLIMATE ioa.factsanddetails.com

DANGEROUS ANIMALS IN AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

ENDANGERED ANIMALS IN AUSTRALIA: SPECIES, THREATS, TRENDS, CONSERVATION ioa.factsanddetails.com

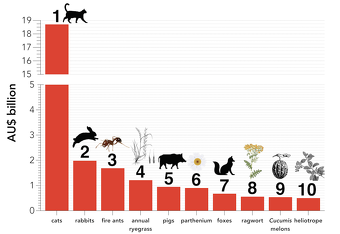

Invasive Plants and Animals Cost Australia US$16.2 Billion a Year — and It Will Get Worse

Corey J. A. Bradshaw and Andrew Hoskins wrote in The Conversation: “Invasive species don’t just cause extinctions and biodiversity loss — they also create a serious economic burden. Our research reveals invasive species have cost the Australian economy at least US$260 billion in the last 60 years alone. Our paper also reveals feral cats are the worst invasive species in terms of total costs, followed by rabbits and fire ants. Some costs involve direct damage to agriculture, such as insects or fungi destroying fruit. Other examples include measures to control invasive species like feral cats and cane toads, such as paying field staff and buying fuel, ammunition, traps and poisons. [Source: Corey J. A. Bradshaw, Flinders University; Andrew Hoskins, CSIRO, The Conversation July 29, 2021]

As a wealthy nation, Australia has accumulated more reliable cost data than most other regions. These costs have increased exponentially over time — up to sixfold each decade since the 1970s. We found invasive species now cost Australia around US$16.2 billion a year, or an average 1.26 percent of the nation’s gross domestic product. Our analysis found feral cats have been the most economically costly species since 1960. Their US$12.3 billion bill is mainly associated with attempts to control their abundance and access, such as fencing, trapping, baiting and shooting. Feral cats are a main driver of extinctions in Australia, and so perhaps investment to limit their damage is worth the price tag.

As a group, the management and control of invasive plants proved the worst of all, collectively costing about US132 billion. Of these, annual ryegrass, parthenium and ragwort were the costliest culprits because of the great effort needed to eradicate them from croplands. Invasive mammals were the next biggest burdens, costing Australia A$63 billion.

For costs that can be attributed to particular states or territories, New South Wales had the highest costs, followed by Western Australia then Victoria. Red imported fire ants are the costliest species in Queensland, and ragwort is the economic bane of Tasmania. The common heliotrope is the costliest species in both South Australia and Victoria, and annual ryegrass tops the list in West Australia. In the Northern Territory, the dothideomycete fungus that causes banana freckle disease brings the greatest economic burden, whereas cats and foxes are the costliest species in the Canberra area and New South Wales.

Cane Toads

Cane toads (Rhinella marina) are large, terrestrial, true toads native to South and mainland Central America that have been introduced to Northern Australia as well as various islands in Oceania and the Caribbean. Cane Toads are big time pests in Queensland and are also found in the Northern Territories and New South Wales. They are unsightly and in some places they gather in huge numbers. Their toxic skin has killed many native species.

Cane toads are the world's largest toads. One 10½ inch specimen at zoo in Iowa weighed slightly over five pounds). In Queensland they are sometimes found living in concentrations of 500 an acre. They have been described as a "mobile cow patties" and "ugly even by toad standards."

Cane toads are considered the most widely-introduced amphibian species in the world and one of the world's most destructive introduced species. They were brought to Australia to control grey-backed cane beetle (Lepidoderma albohirtum) which threatened sugar cane production but there is no evidence that they have controlled any pest in Australia and they are now considered pests themselves not only in Australia but in all Pacific and Caribbean Islands they were also brought to. In their native range cane toads are common but there are natural ways their numbers are kept in check.

Cane toads have been described an "eco-nightmare" in Australia. They capable of covering huge distances, according to a 2006 study in the journal Nature. Cane toads can quickly colonize and take over habitats, due in part to the ability of female cane toads to produce up to 30,000 eggs in a season every year for their 10- to 15-year lifespan . Cane toads can move up to 1.8 kilometers in one night. By 2006, they were found in an area covering over a million square kilometers.

RELATED ARTICLES:

CANE TOADS IN AUSTRALIA: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

CANE TOAD PESTS IN AUSTRALIA: WILDLIFE AND EFFORTS TO GET ROD OF THEM ioa.factsanddetails.com

Foxes in Australia

Introduced European red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) are a serious conservation problem in Australia. A 2012 study estimated there were more than 7.2 million red foxes in Australia and their number was growing). Within 100 years of their introduction, they foxes spread across continental Australia and currently inhabits all regions of the continent with the exception of the tropical northeastern in Queensland. About the the only good thing that can be said about them is that they they eat a lot of introduced rabbits.

European red foxes foxes were brought to Australia for the purpose of recreational hunting by European settlers in search of challenging prey and to uphold the traditional of fox hunting as practiced in England. They were initially introduced to the British colonies of Van Diemen's Land (Tasmania) as early as 1833, and to the Port Phillip District and Sydney Regions of New South Wales as early as 1845. Red foxes were hunted by sportsmen around Melbourne in the 1860s and were firnly entrenched in Adelaide and Sydney by 1890, Queensland by the 1920s and Western Australia by the 1930s. Interestingly, even though they were first introduced to Tasmania, a permanent population of them was not established there untol 2010.

Most extinctions of animals in Australia are due or at least partly due to foxes. Red foxes are now one of most aggressive predators in Australia. They kill large number of marsupials. They have have decimated wildlife in Western Australia and contributed the extinction of ten native mammals. The spread of the red foxes corresponds directly with the declining populations of brush-tailed, burrowing and rufous bettongs, Greater bilbies, numbats, bridled nailtail wallabies and quokkas. Most of these species now only live in limited areas (such as islands) where red foxes are absent or rare. In 2016, researchers documented that some red foxes in Australia can to climb trees to look for birds, baby koalas and other creatures such as sugar gliders dispelling the long-held belief that creatures that lived in trees were safe from them.

Urban Foxes of the Melbourne Area

Larissa Dubecki wrote in The Age: Lured by plentiful scrap food in Melbourne's rubbish bins and back yards, there are more foxes in Melbourne than many rural areas. Conservative estimates put the figure at 12 foxes per square kilometer in the Melbourne metropolitan area, which is higher than the average for rural areas, says scientist Penny Fisher from the Victorian Animal Research Institute. "They live in creek beds, parks; they're in large numbers at the Docklands where they live in deserted warehouses and shipping containers," she says. [Source: Larissa Dubecki, The Age, June 14, 2001 ]

They have been sighted in the early hours in Bourke Street and, last month, one was sucked into the engine of a departing Boeing 737 at Melbourne Airport. Mark Fenby, a fox catcher with Outfoxed pest control, is amused by the naivety of city dwellers when it comes to foxes. Foxes have "always lived in the city", he says. "People think they don't live here and then they call me to get one out of their back yard. I wouldn't be in business if they didn't live in the city." He reckons there are tens of thousands living in Melbourne and he's caught about 100 in the past month. He catches them in a broad band of suburbs including Prahran and Eltham. He also catches a lot in Camberwell.

The night-hunting fox likes to eat native wildlife, says Linton Staples, managing director of Animal Control Technologies. "They'll eat anything. Any species of ground-nesting animal is at risk." Foxes prey on a range of small creatures weighing up to 10 kilograms, which includes possums and ducks, but they do not seem to bother cats. They tend to live unnoticed until they nest beneath a house or in its roof, where their rustlings are often mistaken for possum noises.

Efforts to Control Foxes in Australia

The main forms of control are baits, typically containing 1080 poison, and offering bounties for killed foxes. Fox hunting is legal in all states and they are typically shot with the aid of spotlighting at night or attracted using fox whistles during the day. The eyeshine signature (from the tapetum lucidum in the eye) of foxes, and body shape and silhouette are used to identify them. Local eradication programs have been been hampered by the denning behaviour and nocturnal habits of foxes. [Source: Wikipedia]

At one time farmers in some some area lost five percent of their newborn lambs to foxes. To ward of the predators, Marabou Pro-Products produced a foul-tasting green paint that scared off foxes when applied to the lamb's neck. Farmers ravaged by dingoes also bought some of the stuff.

Within smaller fenced reserves, getting rid of feral cats and red foxes can allow the reintroduction of endangered mammal species. However, such efforts can can be very time-consuming, costly and labour-intensive. At the Australian Wildlife Conservancy's Pilliga reserve, a red fox nicknamed Rambo evaded all attempts to trap, poison, or shoot him for four and a half years, delaying planned mammal reintroductions until the fox's presumed death in 2022.

The reintroduction of competitive species has also been suggested as a method of control. Research by the CSIRO concluded that the presence of dingos not only decreases the presence of foxes but increases native fauna. Chris Johnson of James Cook University and Euan Ritchie of Deakin University have advocated the reintroduction of Tasmanian devils to the mainland to perform a similar role, as evidenced by the past eradication of foxes from Tasmania, as well as to ensure the ongoing survival of that native species.

Mouse Plagues in Australia

The mouse populations in Victoria can reach plague proportions. Some granaries are infested with so many rodents they look as if they have a coat of fur. The populations soar during abundant grain harvests brought on by periods of high rainfall. When the harvests fall the population decreases as a result of disease and cannibalism. In 1931 the Nullabar Plain town of Loongana was invaded by an army of mice. It was so bad a stationmaster SOSed for help saying: "Rest is impossible. Everywhere one looks are thousands of animals which seem to have come out of the sky. They are eating everything...attacking furniture and bedding.

House mice (Mus musculus) are an introduced species in Australia. It is believed to they first arrived as stowaways on board the First Fleet of British colonists in 1788. An early localised plague of mice occurred around Walgett in New South Wales in 1871. In 1872 another plague was recorded near Saddleworth in South Australia with farmers ploughing the soil to destroy mice nests. [Source: Wikipedia, Google AI]

Mouse plagues occur periodically throughout Australia. They mostly occur in the grain-growing regions in southern and eastern Australia, as often as every four years. Aggregating around food sources during plagues, mice can reach a density of up to 3,000 per hectare (1,200 per acre). The plagues destroy crops and grain stores. Mice cause damage to homes and businesses by chewing electrical wires and invading buildings, in the process driving people nuts and impacting agricultural livelihoods.

Mice reproduce rapidly, with a female producing many offspring every three weeks, allowing their numbers to quickly expand exponentially and reaching the millions. Modern farming methods that involve sowing crops directly into old stubble, for environmental reasons, have inadvertently created more mouse food and cover. Using zinc phosphide coated grain is the primary control method. Homemade and commercial traps are not always effective against large infestations. Residents protect their homes by using materials like steel wool to close hole and block entry points. Introducing barn owls into plagued areas by placing nesting boxes has been suggested as a control method. The MouseAlert app allows for the reporting of mice and management activities to help coordinate future control efforts.

The plague of 1917 was one of the largest mouse plagues in Australia. It occurred in and around the Darling Downs area of Queensland, areas around Beulah, Campbells Creek and Willenabrina in Victoria and parts of South Australia including Balaklava. Eventually mice reached the Goldfields-Esperance and Wheatbelt regions of Western Australia. A mouse plague occurred in 2020-2021 in Victoria, Queensland and New South Wales after favourable breeding conditions were created after periods of drought followed by heavy rains, which provide abundant food and shelter. In March 2021, mice were stripping food and other items from the shelves of a supermarket in Gulargambone (382 kilometers (237 miles) north west of Sydney). Health concerns for people were raised when mice killed by baits were found in drinking water tanks. Mice chewing through walls and ceilings, and eating crops and grain stores were estimated to have caused $100 million in damage. Homeowners setting traps were reporting catching 500 to 600 mice per night. The plague caused the complete evacuation (420 inmates and 200 staff) of the Wellington Correctional Centre in June 2021 as dead mice and damage to infrastructure led to concerns for health and safety of inmates and staff.

Rabbits in Australia and the Damage They Cause

European rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus) are one of the most destructive introduced species in Australia. A 2022 study by PNAS, a peer reviewed journal of the US National Academy of Sciences, estimated there were 200 million rabbits in Australia. They have caused hundreds of millions of dollars worth of damage, primarily by eating crops and grass and shrubs grazed on by cattle, sheep and other livestock. Their munching also causes erosion and the destruction of native plants. The burrowing activity of rabbits speeds up decertification

Delphine Paysant of AFP wrote: The rabbit may look small and placid — yet it is voracious in the extreme. Herbs, bulbs, seeds, shrubs — its appetite extends to all kinds of herbaceous plant. This contributes to desertification of the outback, deprives other species of food and also eats away at crops.The agricultural and horticultural damage wrought by the critters comes in at some 200 million Australian dollars ($130 million) each year, according to the Western Australian ministry for agriculture and food. [Source: Delphine Paysant, AFP, September 3, 2023]

European rabbits inhabit about 70 percent of the Australia’s land area. They can have seven litters, with an average five offspring each years, and they can reach maturity in as little as three months. They breed so rapidly it is theoretically possible for one randy pair to generate a population of nearly 14 million rabbits in three years. Their numbers can rise and fall reaching peaks when food is plentiful such as after rainy periods and falling during times of drought. abbits are particularly damaging when their populations boom and they consume large amounts vegetation, destroying grasslands and depriving native fauna, including kangaroos and wallabies, and domesticated animals, such as sheep and cattle, of food.

"Oh-h-h the bastards" a manager of a station near Alice Springs told National Geographic journalist Rick Gore, "A couple of years ago this was all grass. Now its as bare as a baby's bottom. Their's been lots of rain recently, but it brings the sprouts up just enough for the rabbits to eat. There's rabbits from here to another seventy miles west. It's got beyond a joke. I'm wondering whether this land will ever recover."

Ironically, when the wool market crashed and the popularity of rabbit meat in Spain and Italy increased, rabbits, pound for pound, are worth five times more than sheep.

History of Rabbits in Australia

European rabbits were first introduced to Australia in the 18th century with the First Fleet, and later became widespread, because of Thomas Austin, a sheep farmer. In 1859, he released wild rabbits on his property near Winchelsea, Victoria for sport hunting. These rabbits, along with earlier domestic importations, rapidly spread across the continent, creating the fastest known invasion by a mammal worldwide. Now, for many Australians, “rabbit” is synonymous with “pest”.

The first reported of European rabbit population boom was in 1827 in Tasmania. An article in the Colonial Times and Tasmanian Advertiser read: "the common rabbit is becoming so numerous throughout the colony, that they are running about on some large estates by thousands. We understand, that there are no rabbits whatever in the elder colony" i.e., New South Wales. At the same time in New South Wales, Cunningham noted, "rabbits are bred around houses, but we have yet no wild ones in enclosures." He also mentioned the scrubby, sandy rubble between Sydney and Botany Bay would be ideal for farming rabbits.

Twenty-four rabbits brought from England were released in 1859 on Austin’s estate in Victoria. Rabbits were introduced around Melbourne in the 1860s. They spread to Adelaide and Sydney by 1870, and Queensland and Western Australia by the 1910s. By the 1940s there were 600 million of them — or one for every 100 people.

From their early years in Australia, rabbits benefited from a general absence of predators and were able to adapt to their mostly new, drier climate. They spread at a rate of 110 kilometers (65 miles) a year. Within 70 years, they had occupied around 70 percent of Australia's land mass. That made it "the fastest known invasion by a mammal anywhere in the world," according to a report by Australia's national science agency CSIRO.[Source: Delphine Paysant, AFP, September 3, 2023]

The myxomatosis virus, a disease introduced from Brazil in the 1950s nearly wiped them out, reducing the population to 100 million within two years. The disease which causes fatal tumours in rabbits, was initially heralded as a success. But survivors quickly developed an immunity to the disease. In the 1980s rabbit populations surged when three straight wet years produced enough vegetation for them to feed and multiply. By 1991 there were about 200 million of them. Australia also introduced a Spanish flea, supposed to spread disease among rabbits. Again, the plan failed. Worse, the parasite infected other species.

Efforts to Control Rabbits in Australia: Fences, Shooters and Diseases

For more than a century, authorities have been doing everything they can to reduce rabbit numbers and mitigate the damge they cause. Delphine Paysant of AFP wrote: Intensive hunting, traps, bulldozers to destroy burrows, poison or even explosives — everything has been tried. But the rabbit has resisted and its numbers have progressed. In 1901, Australia decided to construct an 1,800 kilometer-long (1,118 miles) barrier — the Rabbit-Proof Fence — in a bid to stop the furry creatures proliferating to the country's western agricultural lands. Yet by the time construction was completed, rabbits had already reached the other side. An extension followed then another, taking the fence to beyond 3,000 kilometers (1864) of barriers and fences. All in vain. Australia tried plan B — introducing predators, such as the fox. The 'cure' proved to be worse than the disease. It turned out the fox preferred to target easier prey such as small marsupials endemic to the country and already threatened with extinction. [Source: Delphine Paysant, AFP, September 3, 2023]

Australian ranchers have combated the rabbits by digging up their warrens, spraying pesticides, sicking dogs on them, and hiring professional rabbit killers, who shoot and trap the rodents and then sell their skins and meat on the world market. On one farm alone 60,000 rabbits were killed in one month. [National Geographic Geographica, June 1991].

Rabbit shooters have killed millions of rabbits and have exported many to Europe as meat. They usually hunt at night, picking off rabbits stunned by bright headlights with a.22 rifle. One shooter, who slept in a trailer during the day and hunted from his Toyota pick-up at night, said he sometimes bags 400 rabbits a night. "I gut'em and pair'em and put'em in the chiller for Perth," he said.

The latest strategy to control rabbits has been deliberate introduction of rabbit calcivirus, a leporine hemorrhagic disease, which miraculously does not harm any other Australian animals. In the mid-1990s the Australian rabbit population was decimated by a virus native to China and Europe that was being experimented with on an island off os South Australia but was accidentally introduced to the mainland, perhaps by a bush fly or another insect that had bitten an infected rabbit and was blown by freak winds three miles across the ocean to mainland sometime in 1995. The disease, which poses no threat to humans or other animals, killed its victims in less than three days. It first causes the blood coagulation and clot, which robs the brain and part of the body of oxygen, which lead to lethargic behavior. The rabbits ultimately die of acute respiratory and heart failure.

The disease spread rapidly across Australia. Five million rabbits were killed in a few months. In some infected areas, the death rate was 98 percent. Originally the disease was supposed to be introduced to the mainland in 1998 and carefully controlled before it was released nationwide. After the accident released it quickly spread to the Flinders Range, 800 kilometers (500 miles) from the original experimentation site. There were also worries in the scientific community that the disease might mutate. On top of this, the highly contagious pathogen can spread quickly to other countries via mosquitoes.

Around 2000, the disease arrived in New Zealand, which also had rabbit population issues. Delphine Paysant wrote in AFP: The stoat, introduced as a predator to the rabbit left deprived as the population dropped, fell back on targeting the kiwi, a bird endemic to the island which became threatened in turn. Both Australia and New Zealand represent classic cases in terms of what not to do regarding the introduction and management of invasive species, says Elaine Murphy, principal scientist at New Zealand's Department of Conservation and an expert on introduced mammals and the threats to diversity they pose.While rabbit numbers look to have stabilised under the 300 million mark, the Australian government says it is maintaining research into means of permanently stemming the propagation problem. [Source: Delphine Paysant, AFP, September 3, 2023]

Campaigns Against Feral Animals

In many case wildlife managers have resorted to poisoning introduced species or allowing shooters to go after them. The Department of Conservation and Land Management launched a program called Project Eden, whose purpose has been to help endangered species by killing ferals. The projects receives government funds and private donations from supermarkets and other businesses. One Project Eden project involved fencing off the 1,050-square- kilometer (405-square-mile) Peron Peninsula and trapping and killing goats, foxes and cats. Cat and goat numbers were reduced and the foxes were almost eliminated. Native species were released into the area and seem to thriving.

In 2009 and 2010, Australia carried out the world’s biggest pest eradication program on the sub-Antarctic Macquarie Island, where thousands of mice and rabbits are damaging the world-heritage island. Reporting from Commonwealth Bay there, Pauline Askin wrote in Reuters Life!: The pests are causing so much environmental damage that native flora and fauna, including species of seals, penguins and sea birds, are at risk, Australian wildlife officials say. The eradication exercise involved aerial baiting and about 12 hunters and 11 dogs and started in May 2010. It is “the largest eradication worldwide for rabbits, rats or mice,” said Keith Springer, eradication manager with the Parks and Wildlife Services in Australia’s Tasmania state. [Source: Pauline Askin, Reuters Life!, December 15, 2009]

Australia’s Macquarie Island lies about half way between New Zealand and Antarctica, where the cold polar water meets warmer water, and is one of the few islands in the Pacific sector of the Southern Ocean where fauna in the region can breed. The long, thin island is a breeding place for millions of seabirds, mostly penguins. Seals, including the world’s largest species, the elephant seal, haul out on the beaches for breeding. Around 80,000 elephant seals arrive on Macquarie each year. Fur seals are beginning to re-establish populations on the island after being nearly exterminated by commercial operations in the early 19th century.

The US$22 million eradication project required about 300 tonnes of poisonous bait being scattered over the island. But the key to success will be the delivery of fresh bait using large storage containers that can transport the bait and keep it protected from weather, condensation and pests. Six English Springer spaniels are being trained to detect rabbits, but ignore penguins, seals and seabirds. Two of the spaniels, Ash and Gus, traveled to the island in late October 2009 for training in the conditions they will face on the island during winter 2010. “The two dogs performed really well on Macquarie but were a bit overwhelmed by the number of rabbits at first, they didn’t know which scent to follow first,” said Springer.

Insulated kennels have been built to ensure the dogs can withstand Macquarie’s extreme oceanic climate with heavy cloud, strong westerly winds and a rainfall of 900 mm a year. “The dog kennels are made out of 44 gallon drum on its side with an insulated floor and a weather proof dog flap at the entry and a tiny little porch out the front,” said Marty Passingham who is now at Commonwealth Bay as part of an expedition to restore Australian Antarctic explorer Sir Dougas Mawson’s huts. “In May, the conditions for the dogs will be cold, wet and snowy.”

Rabbits were introduced to Macquarie by seal hunters as a source of food around 1878. It is believed there are between 60-100,000 rabbits currently on the island, which is located 1,500 kms (930 miles) southeast of Hobart, Tasmania. Cats were also brought to the island by seafarers to stop mice eating food stores, but their population also exploded. The cats kept the mice and rabbit populations down, but also killed tens of thousands of seabirds. A cat eradication program on Macquarie started in 1985 with the last cat killed in 2000. But when the cats died, rabbit numbers increased rapidly and have now altered large areas of island vegetation.

Dana Bergstrom of the Australian Antarctic Division was the lead author of study on the cat eradication published in British Ecological Society's Journal of Applied Ecology in January 2009. "Our study shows that between 2000 and 2007, there has been widespread ecosystem devastation and decades of conservation effort compromised," Bergstrom said in a statement. The unintended consequences of the cat-removal project show the dangers of meddling with an ecosystem — even with the best of intentions, the study said. "The lessons for conservation agencies globally is that interventions should be comprehensive, and include risk assessments to explicitly consider and plan for indirect effects, or face substantial subsequent costs," Bergstrom said. [Source: Associated Press, January 14, 2009]

Several conservation groups, including the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Birds Australia, said the eradication effort did not go far enough and that the project should have taken aim at all the invasive mammals on the island at once. "It would have been ideal if the cats and rabbits were eradicated at the same time, or the rabbits first and the cats subsequently," said University of Auckland Prof. Mick Clout, who also is a member of the Union's invasive species specialist group.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org , National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, David Attenborough books, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2025