Home | Category: Nature, Environment, Animals

ANIMALS OF NEW ZEALAND

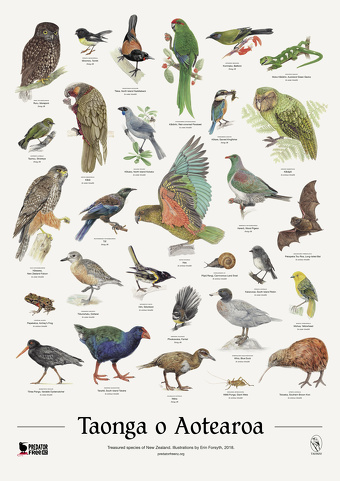

Because New Zealand was isolated from the rest of the world for some 85 million year, much of its indigenous flora and fauna evolved independently and became unique. Native insects, spiders, snails, earthworms, reptiles and many freshwater fish, plants and birds are found nowhere else in the world.

The first people to arrive on New Zealand found no large mammals: no deer, no antelope, no bears, or large cats or even kangaroos like in Australia. The only mammals were small bats and the only predators were falcons, hawks, eagles and other meat-eating birds. Occupying the niches taken by large mammals were large flightless bird. Occupying the niches of small mammals were smaller flightless birds and large insects. The only other invertebrates were lizards that had their origins in the early dinosaur age.

As many as 80,000 species of native animals, fungi and plants are believed to live in New Zealand. Only about 30,000 have been described and named. It is said that New Zealand is home to only two native mammal species — two bats — but this doesn’t include marine mammals. If these are included then the broader New Zealand Region has about 63 recognized native mammal species or subspecies.

Among the Unusual species giant snails and unusual mountain frogs. Some of the land mammals introduced to New Zealand have become pests, such as rabbits, deer, pigs Australian possums. New Zealand has only three native amphibian species, all of which are primitive frogs from the genus Leiopelma. These are Archey's frogs, Hamilton's frogs, and Hochstetter's frogs. Maud Island frogs, previously thought to be a separate species, are now considered the same species as Hamilton’s frog. In addition to these native species, there are three introduced frog species that are also found in the country. There are no native salamanders in New Zealand.

New Zealand is home to 106 known native reptile species, all of which are unique to the country and are either endemic tuataras, skinks, or geckos. There are no native snake species in New Zealand, only an introduced one and a visiting resident sea snake. The New Zealand reptile fauna, known as herpetofauna, includes the ancient tuatara, more than 100 species of endemic lizards (skinks and geckos), and a visiting sea turtle, though these are not included in the native terrestrial herpetofauna count.

New Zealand has over 200 native bird species, with a number of these being unique to the country (endemic). While the precise total varies depending on how species are counted and whether extinct species are included, the numbers are generally in the range of 200–250 total native species, which includes seabirds, shorebirds, and wetland birds as well as land birds.

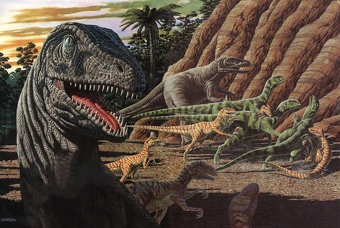

Dinosaurs in New Zealand

Dinosaurs lived in what is now New Zealand during the Cretaceous period (145 to 66 million years ago). Evidence include fossils of a sauropod, a theropod, and an ankylosaur found in areas like Hawke's Bay. However, the evidence consists of rare, fragmented fossils, making it difficult to identify specific species, though they likely resembled dinosaurs found in Australia, Antarctica and other southern hemisphere location. The discovery of a toe bone from a large theropod in the 1970s proved the existence of dinosaurs in New Zealand, changing the prior belief that the landmass was too small for them to exist. [Source: Google AI]

Joan Wiffen was the paleontologist who discovered the first dinosaur bone in New Zealand in 1975 — a toe bone from a large, carnivorous theropod. Mangahouanga Stream in Hawke's Bay, has yielded significant discoveries, including the first theropod bone and later, a fragment of a giant sauropod (titanosaur). One of the more significant discoveries, in the 1980s, was of "armored dinosaur" (ankylosaur). A vertebra found in 1999 was identified as belonging to a Titanosaur — one of the largest known dinosaurs, confirming the presence of sauropods in New Zealand.

As a whole few dinosaur fossils have been found in New Zealand. New Zealand's landmass broke away from Gondwana about 85 million years ago, carrying the existing flora and fauna with it. The conditions in New Zealand were not ideal for fossilization, leading to only fragmentary remains being preserved. The bones found are often single pieces, sometimes found in concretions formed after being swept into the sea and then pushed back to the surface by geological activity.

For more information on this topic see The Hunt for New Zealand’s Dinosaurs by Vaughan Yarwood, New Zealand Geographic, July–September 1993 nzgeo.com

New Zealand’s Isolation and Its Unique Animal Life

Elizabeth Kolbert wrote in The New Yorker: New Zealand can be thought of as a country or as an archipelago or as a small continent. It consists of two major islands — the North Island and the South Island, which together are often referred to as the mainland — and hundreds of minor ones. It’s a long way from anywhere, and it’s been that way for a very long while. The last time New Zealand was within swimming distance of another large landmass was not long after it broke free from Australia, eighty million years ago. The two countries are now separated by the twelve-hundred-mile-wide Tasman Sea. New Zealand is separated from Antarctica by more than fifteen hundred miles and from South America by five thousand miles of the Pacific. [Source: Elizabeth Kolbert, The New Yorker, December 22 & 29, 2014]

As the author David Quammen has observed, “Isolation is the flywheel of evolution.” In New Zealand, the wheel has spun in both directions. The country is home to several lineages that seem impossibly outdated. Its frogs, for example, never developed eardrums, but, as if in compensation, possess an extra vertebra. Unlike frogs elsewhere, which absorb the impact of a jump with their front legs, New Zealand frogs, when they hop, come down in a sort of belly flop. (As a recent scientific paper put it, this “saltational” pattern shows that “frogs evolved jumping before they perfected landing.”) Another “Lost World” holdover is the tuatara, a creature that looks like a lizard but is, in fact, the sole survivor of an entirely separate order — the Rhynchocephalia — which thrived in the early Mesozoic. The order was thought to have vanished with the dinosaurs, and the discovery that a single species had somehow managed to persist has been described as just as surprising to scientists as the capture of a live Tyrannosaurus rex would have been.

At the same time, New Zealand has produced some of nature’s most outlandish innovations. Except for a few species of bats, the country has no native mammals. Why this is the case is unclear, but it seems to have given other groups more room to experiment. Weta, which resemble giant crickets, are some of the largest insects in the world; they scurry around eating seeds and smaller invertebrates, playing the part that mice do almost everywhere else. Powelliphanta are snails that seem to think they’re wrens; each year, they lay a clutch of hard-shelled eggs. Powelliphanta, too, are unusually big — the largest measure more than three and a half inches across — and, in contrast to most other snails, they’re carnivores, and hunt down earthworms, which they slurp up like spaghetti.

New Zealand, Gondwana, and Island Ecology

New Zealand broke off from the supercontinent Gondwana about 85 million years ago. This event initiated the formation of the Tasman Sea between New Zealand and Australia, and by 55 million years ago, New Zealand had drifted to its current position, becoming isolated in the Pacific Ocean. In contrast, Australia broke away from the supercontinent Gondwana in stages, with the initial separation occurring around 130-100 million years ago as India and Antarctica began to drift away, and the final definitive separation from Antarctica happening around 45-55 million years ago. Australia then continued its journey northwards as a separate continent.

Derek Grzelewski wrote in New Zealand Geographic: New Zealand was once an island Eden, an ark that broke off the ancestral supercontinent of Gondwana and never quite arrived anywhere, but stayed afloat in the South Pacific, becoming a world unto itself. [Source: Derek Grzelewski, New Zealand Geographic. January-March 2000]

There are several such arks anchored around the planet — Mauritius, Hawaii, Galapagos — which, though distant and distinct from one other, all have one thing in common. Life on them evolved in isolation from a pool of original stowaways, and subsequent immigrants were few, usually birds and insects. According to eminent American naturalist Edward 0. Wilson, such islands are the key to our understanding of how nature works, because the links between species are simpler and clearer than in continental ecosystems. The ecological tapestry of islands is woven more coarsely and contains fewer threads.

In 1967, Wilson and mathematical ecologist Robert MacArthur published their findings in a book entitled The Theory of Island Biogeography, which has become a canon of evolutionary biology. Each island, they proposed, could sustain only so many species, so if a new species arrived and colonised the island, an older resident would be forced into extinction. The arrival of human settlers to such islands — along with the entourage of vermin that accompanied them — typically unleashed a wave of extinctions and set the ecological tapestry unravelling.

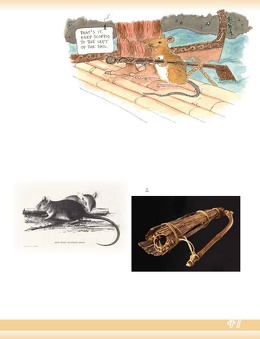

Are Rats Proof That People Arrived in New Zealand 2,000 Years Ago?

The widely held belief is that first human inhabitants of New Zealand arrived sometime in the A.D. 1200s. But there are those who argue they arrived earlier and offer rats as proof. In 1996, Richard Holdaway, an independent extinction biologist, presented evidence that rats first made landfall on New Zealand as early as 2000 years ago. Laura Sessions wrote in Natural History Magazine: That date has called into question the entire sequence of prehistoric events that shaped New Zealand — and, not surprisingly, has fueled much debate in New Zealand about the strength and validity of Holdaway’s evidence. [Source: Laura Sessions, Natural History Magazine, March 2003]

Holdaway and Nigel Prickett of the Auckland Museum have devoted much attention to answering two of New Zealand’s most sensitive archaeological questions. When did settlers ancestral to today's Maori arrive in New Zealand, and were they the first to introduce rats to its islands? Or were rats, which are not native to New Zealand, already there, left behind by earlier voyagers who are not yet visible in the archaeological record? [Source: Eric A. Powell, Archaeology magazine, Volume 56 Number 2, March/April 2003]

From 1991 until 1995 Holdaway took part in a collaborative study to examine fossils for signs that early Polynesian settlement had led to changes in animal populations and the mix of animal species Eric A. Powell wrote in Archaeology magazine: The Pacific rat (Rattus exulans), called kiore in Maori, is considered proxy evidence for human settlement throughout the Pacific. Rats are not native to Polynesia and they cannot swim, so they must have been transported from island to island as stowaways or as food on the great canoes the Polynesians piloted across the ocean. In 1996, Holdaway published a paper that presented radiocarbon dates on rat bones from nonarchaeological sites in New Zealand. The bones came from deposits that were created by birds, most likely owls. Holdaway's dates showed rats in the New Zealand archipelago nearly 2,000 years ago, implying humans had visited New Zealand at the same time. His data was criticized on several fronts. Objections were raised concerning the poor preservation of the rat bones, and critics pointed out that rat diet and the contamination of the bone by ancient carbon could have thrown off the dates.

Holdaway makes no claims for permanent early settlement, concluding that the rats were left behind by explorers who either failed or did not attempt colonization. He points out that had early explorers stayed for any significant period of time, they would have devastated the local fauna, particularly the flightless moa, an event that surely would have shown up in the archaeological record. He thinks the people who introduced the kiore stayed only a few years at most.

Janet M. Wilmshurst Atholl J. Anderson, Thomas F. G. Higham, and Trevor H. Worthy wrote in PNAS: we provide a reliable approach for accurately dating initial human colonization on Pacific islands by radiocarbon dating the arrival of the Pacific rat. Radiocarbon dates on distinctive rat-gnawed seeds and rat bones show that the Pacific rat was introduced to both main islands of New Zealand ≈A.D. 1280, a millennium later than previously assumed. This matches with the earliest-dated archaeological sites, human-induced faunal extinctions, and deforestation, implying there was no long period of invisibility in either the archaeological or palaeoecological records. [Source: Janet M. Wilmshurst Atholl J. Anderson, Thomas F. G. Higham, and Trevor H. Worthy, PNAS, June 3, 2008]

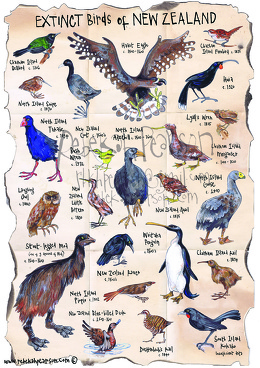

Impact of the First People on New Zealand's Animals

Humans arrived in New Zealand from Polynesia about A.D. 1300. They and the animals they brought with them, namely dogs and rats, were responsible for the exterminated many of New Zealand indigenous animals, including moas and at least 18 other species of bird including the flightless New Zealand goose, the Fjordland crested penguin, the giant rail (more than a meter tall) as well as several species of lizards and insects. The devastating ecological consequences of human arrival are well documented on many East Polynesian islands and show striking similarities in terms of deforestation and faunal extinctions or declines.

The first people to arrive on New Zealand found no large mammals: no deer, no antelope, no bears, or large cats or even kangaroos like in Australia. The only mammals were two species of small bat and the only predators were falcons, hawks, eagles and other meat-eating birds.

The colonization of New Zealand by human triggered a devastating transformation, also in a relatively short period of time. There was widespread deforestation. Overhunting contributed to widespread faunal extinctions and the decline of marine megafauna, fires destroyed lowland forests. The introduction of the , Pacific rat is believed have led to the extinction of bird and reptile species. [Source: Janet M. Wilmshurst Atholl J. Anderson, Thomas F. G. Higham, and Trevor H. Worthy, PNAS, June 3, 2008]

Kate Evans wrote in Eos Science News: There are discrepancies between Antarctic Peninsula ice core tells about burning in New Zealand and that preserved in the charcoal records found in lake sediments across New Zealand. Both show a sharp increase in fire around 1300, but the ice core shows soot levels peaking in the 16th and 17th centuries, whereas the lake sediments show burning falling away, then rising to a new peak around 1840, coinciding with mass European immigration and land clearing. [Source: Kate Evans, Eos Science News, American Geophysical Union, October 26, 2021]

For Joe McConnell from the Desert Research Institute (DRI) in Reno, Nev., that divergence simply shows local, catchment-level paleofire records aren’t particularly accurate when scaled up—but Winton wondered whether there’s something else going on as well. “The New Zealand local fire record and the Antarctic black carbon record look quite different around the 16th and 17th centuries after the 13th century initial rise. To me that raises exciting questions about other factors that could regulate the ice core signal, such as changes in atmospheric processes or shifts in climate oscillations. What about changes in the hydrological cycle?” Chemical analysis of biomarkers in the soot in these and other ice cores could provide more clarity about what kind of vegetation was burned, she said, and perhaps help to resolve the puzzle. “It would be really interesting to further explore what was going on during that time period.”

Threatened and Endangered Animals in New Zealand

There a number of threatened species in New Zealand, including kakapos, New Zealand fairy terns (tara iti), yellow-eyed penguin (hoiho), New Zealand greater short-tailed bat, kaki (black stilt), Hector’s dolphins and several wēta species. Among the primary threats are introduced predators like stoats, rats, and possums, as well as habitat loss, pollution, and climate change. The Department of Conservation (DOC) uses the New Zealand Threat Classification System (NZTCS) to assess and manage these species.

The kakapo, a large, flightless parrot, is one of New Zealand's most best-known endangered species. The New Zealand fairy tern is critically endangered with only a few breeding pairs left. The Maui dolphin is a subspecies of Hector’s dolphin. It is also critically endangered, with between 50 and 60 left. The Mahoenui giant wēta is a nationally endangered insect whose survival is linked to spiny gorse. New Zealand also has threatened plant species, such as the, coastal peppercress, and limestone cress.

Human developments, such as house construction, have led to habitat loss and fragmentation for many species. Warming sea temperatures are a threat to penguins, and other climate-related issues impact various species. Human activity and pollution, especially on popular beaches, threaten species like the fairy tern. In the past Australian birds such as galahs, cockatoos and lorikeets were sometimes smuggled into New Zealand, laundered there and legally re-exported to Europe and North America.

In 1894, a cat owned by a lighthouse keeper on a small island killed the last 15 Stephen Island wrens, rendering the species extinct. Predator control efforts today include establishing predator-free islands and managing predator populations to protect vulnerable native species. There are also conservation programs focused on restoring and protect critical habitats.

Mammals in New Zealand

New Zealand is home to only two land-based native mammal species — the long-tailed bat and the short-tailed bat (a third, greater short-tailed bat was last seen in 1967 and is considered extinct). But there are numerous marine mammals such as Hector’s dolphins and New Zealand sea lions and other species of whales and dolphins that reside in New Zealand waters. If these are included then the broader New Zealand Region has about 63 recognized native mammal species or subspecies.

There are three resident pinniped species in New Zealand: 1) endemic New Zealand fur seals (kekeno); 2) New Zealand sea lions (pakake/whakahao), and 3) Southern elephant seal which breeds on subantarctic islands. Leopard seals are often seen in New Zealand waters. They primarily inhabit the Antarctic region but show up in New Zealand's waters during autumn and winter

Dolphins in the Fiordland area are famous for welcoming ships into the bays and sounds. There are also places where people swim with dolphins. The major species found in New Zealand include dusky dolphins, Hector's dolphins and bottlenose dolphins.

The waters of New Zealand are on migratory routes and are feeding ground for various whales, including humpback whales, blue whales, pygmy right whales, pilot whales and sperm whales. Southern right whales migrate to some places off the coast of New Zealand. Pygmy right whales are found in waters off New Zealand. They are sometimes mistaken for bowhead whales.

Related Articles:

SEALS AND SEA LIONS IN NEW ZEALAND: SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

SPECIES OF DOLPHIN IN AUSTRALIA AND NEW ZEALAND ioa.factsanddetails.com

COMMON DOLPHINS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND SHORT- AND LONG-BEAKED ONES ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

BOTTLENOSE DOLPHINS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, FEEDING, MATING, SPECIES ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

PILOT WHALES — LONG-FINNED, SHORT-FINNED — CHARACTERISTICS AND BEHAVIOR ioa.factsanddetails.com

WHALE STRANDINGS IN NEW ZEALAND: INCIDENTS, REASONS WHY, RESCUES ioa.factsanddetails.com

BLUE WHALES: CHARACTERISTICS, SIZE, HISTORY, RANGE AND BIG HEART ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

HUMPBACK WHALES: CHARACTERISTICS, FEEDING AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

RIGHT WHALES: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, FEEDING, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

SPERM WHALES: CHARACTERISTICS, SPECIES AND BIG HEADS AND BRAINS ioa.factsanddetails.com

Reptiles and Amphibians in New Zealand

New Zealand is home to 106 known native reptile species, all of which are unique to the country and are either endemic tuataras, skinks, or geckos. There are no native snake species in New Zealand, only an introduced one and a visiting resident sea snake. The New Zealand reptile fauna, known as herpetofauna, includes the ancient tuatara, more than 100 species of endemic lizards (skinks and geckos), and a visiting sea turtle, though these are not included in the native terrestrial herpetofauna count.

Some geckos feed on nectar in the of flowers of native flax. In doing so they help spread the pollen from plant to plant. Sometimes a half dozen or so geckos feed on a single flower and some geckos travel a considerable distance to reach the flowers. It is believed the geckos are the primary source of pollination. Since mammals have been introduced the number of geckos has been reduced and the flax doesn’t pollinate as easily as in the past.

The tuatara, found on islands near the New Zealand mainland, is a two-foot-long reptile that looks like a lizard but actually belongs to a separate order of reptiles (“Rhynchocephalia”) that thrived between 70 and 200 million years ago. Older than dinosaurs, it is regarded as a living fossil like the coelacanth, a fish thought to have become extinct 60 million years ago that was found by a South African fisherman in the Indian Ocean in 1938.

New Zealand has only three native amphibian species, all of which are primitive frogs from the genus Leiopelma. These are Archey's frogs, Hamilton's frogs, and Hochstetter's frogs. Maud Island frogs, previously thought to be a separate species, are now considered the same species as Hamilton’s frog. In addition to these native species, there are three introduced frog species that are also found in the country. There are no native salamanders in New Zealand.

See Separate Articles: TUATARAS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION, UNIQUENESS AMONG REPTILES ioa.factsanddetails.com ; FROGS IN NEW ZEALAND: SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

Birds in New Zealand

New Zealand has over 200 native bird species, with a number of these being unique to the country. The total varies depending on how species are counted and whether extinct species and migratory birds that stop briefly on New Zealand islands are included. The numbers are generally in the range of 200 to 250 total native species, which includes seabirds, shorebirds, and wetland birds as well as land birds.

The first people to arrive on New Zealand found no large mammals: no deer, no antelope, no bears, or large cats or even kangaroos like in Australia. The only mammals were small bats and the only predators were falcons, hawks, eagles and other meat-eating birds. Occupying the niches taken by large mammals were large flightless birds. Occupying the niches of small mammals were smaller flightless birds and large insects. The only other invertebrates were lizards that had their origins in the early dinosaur age.

After the first settlers — Polynesian Māori — arrived in New Zealand about 700 years ago, the environment changed quickly. Several species — most famously moas (Dinornithidae) and Haast's eagles (Hieraaetus moorei) — were hunted to extinction by colonizing peoples. The most damage was caused by habitat loss and degradation and animals brought by the colonizing humans, particularly rats — the Polynesian rat or kiore introduced by Māori and the brown rat and black rat subsequently introduced by Europeans 400 years later. Mice, dogs, cats, stoats, weasels, pigs, goats, deer, hedgehogs, and Australian possums showed up over the years and also put pressure upon native bird species. The flightless birds were especially sensitive. Birds like the kākāpō and kiwi were unable to fly and therefore unable to lay their eggs in elevated areas, with stoats and weasels in particular taking advantage of this and eating their eggs.

In the meantime, birds continue to fly into New Zealand from far away places. The spur-winged plover (Spur-winged lapwing) arrived relatively recently from Australia and has established itself in new Zealand.

RELATED ARTICLES:

BIRDS OF NEW ZEALAND: SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

MOAS: HISTORY, CHARACTERISTICS, REPRODUCTION, EXTINCTION, DE-EXTINCTION? ioa.factsanddetails.com

MOA SPECIES: GIANT, SMALL AND HEAVY-FOOTED ONES ioa.factsanddetails.com

KIWIS: EVOLUTION, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

KIWI SPECIES: NORTHERN, SOUTHERN, SPOTTED, LARGEST, SMALLEST ioa.factsanddetails.com

SOUTHERN BROWN KIWI: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

KIWIS, HUMANS AND CONSERVATION ioa.factsanddetails.com

KEAS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, PLAYFULNESS, INTELLIGENCE, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

KAKAPO: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION, SAVING THEM FROM EXTINCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

KOKAKOS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

SHEARWATERS AND PETRELS ioa.factsanddetails.com

GANNETS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, NESTING AND DIVING ioa.factsanddetails.com

BLACK SWANS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

KINGFISHERS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

NEW ZEALAND PENGUINS: SPECIES, HISTORY, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

LITTLE PENGUINS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New Zealand Tourism Board, New Zealand Herald, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN and various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2025