Home | Category: Nature, Environment, Animals

BIRDS IN NEW ZEALAND

From “New Zealand Birds A Folding Pocket Guide to Familiar Species” Amazon

New Zealand has over 200 native bird species, with a number of these being unique to the country. The total varies depending on how species are counted and whether extinct species and migratory birds that stop briefly on New Zealand islands are included. The numbers are generally in the range of 200 to 250 total native species, which includes seabirds, shorebirds, and wetland birds as well as land birds.

The first people to arrive on New Zealand found no large mammals: no deer, no antelope, no bears, or large cats or even kangaroos like in Australia. The only mammals were small bats and the only predators were falcons, hawks, eagles and other meat-eating birds. Occupying the niches taken by large mammals were large flightless birds. Occupying the niches of small mammals were smaller flightless birds and large insects. The only other invertebrates were lizards that had their origins in the early dinosaur age.

After the first settlers — Polynesian Māori — arrived in New Zealand about 700 years ago, the environment changed quickly. Several species — most famously moas (Dinornithidae) and Haast's eagles (Hieraaetus moorei) — were hunted to extinction by colonizing peoples. The most damage was caused by habitat loss and degradation and animals brought by the colonizing humans, particularly rats — the Polynesian rat or kiore introduced by Māori and the brown rat and black rat subsequently introduced by Europeans 400 years later. Mice, dogs, cats, stoats, weasels, pigs, goats, deer, hedgehogs, and Australian possums showed up over the years and also put pressure upon native bird species. The flightless birds were especially sensitive. Birds like the kākāpō and kiwi were unable to fly and therefore unable to lay their eggs in elevated areas, with stoats and weasels in particular taking advantage of this and eating their eggs.

In the meantime, birds continue to fly into New Zealand from far away places. The spur-winged plover (Spur-winged lapwing) arrived relatively recently from Australia and has established itself in new Zealand.

RELATED ARTICLES:

MOAS: HISTORY, CHARACTERISTICS, REPRODUCTION, EXTINCTION, DE-EXTINCTION? ioa.factsanddetails.com

MOA SPECIES: GIANT, SMALL AND HEAVY-FOOTED ONES ioa.factsanddetails.com

KIWIS: EVOLUTION, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

KIWI SPECIES: NORTHERN, SOUTHERN, SPOTTED, LARGEST, SMALLEST ioa.factsanddetails.com

SOUTHERN BROWN KIWI: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

KIWIS, HUMANS AND CONSERVATION ioa.factsanddetails.com

KEAS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, PLAYFULNESS, INTELLIGENCE, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

KAKAPO: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION, SAVING THEM FROM EXTINCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

KOKAKOS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

SHEARWATERS AND PETRELS ioa.factsanddetails.com

GANNETS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, NESTING AND DIVING ioa.factsanddetails.com

BLACK SWANS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

KINGFISHERS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

NEW ZEALAND PENGUINS: SPECIES, HISTORY, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

LITTLE PENGUINS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

New Zealand — Land of the Birds and Flightless Birds

From “New Zealand Birds A Folding Pocket Guide to Familiar Species” Amazon

The Australian naturalist Tim Flannery has described New Zealand’s bird-dominated ecosystem as a “completely different experiment in evolution.” It is like, he wrote “what the world might have looked like if mammals as well as dinosaurs had become extinct 65 million years ago, leaving the birds to inherit the globe.” Jared Diamond said New Zealand's native fauna is the nearest we’re likely to come to “life on another planet.” [Source: Elizabeth Kolbert, The New Yorker, December 22 & 29, 2014]

New Zealand is sometimes viewed as the land of flightless birds. It has seen at least 44 species of flightless or almost flightless birds both past and present, including 15 species (like the giant Moa) that became extinct after the arrival humans and 16 extant species remaining as of 2017. If you include species that went extinct before the arrival of humans the total of flightless birds in New Zealand is closer to 40-45 species.

Most of flightless birds that remain today mostly live in small isolated populations, often on predator-free islands, and are threatened, endangered or in danger of becoming extinct. Wekas are a flightless bird that belong to the rail family. The inhabitant many offshore islands, where they greet new arrivals on the beach and expect them to have food. The descendants of some of New Zealand's flightless birds were flying birds that reached the islands by air and evolved into flightlessness while on New Zealand. Others are the descendants of birds that lived on the islands of New Zealand when they broke away from Gondwana 80 to 85 million years ago, Many became flightless because they had no mammal predators.

Bird Species in New Zealand

Native New Zealand birds include the tui, bellbird and kea. The morepork owl which usually dines on lizards and mice gets it name from its call "morepork, morepork." The kakapo is a large, fat, seriously endangered parrot with a mysterious foghorn-like call. The bellbird growls and mimics other birds before producing its own song. It has traditionally been so admired by the Maori they were sacrificed and eaten after a birth to ensure the child had a good singing voice and speaking manner. The New Zealand pigeon is a bird the Maori ate for food. It is plump, produces a loud thrashing noise when it flaps its wings and has difficulty getting off the ground but has managed to thrive because of its prodigious breeding habits.

Many species of native New Zealand birds are known for their tameness and curiosity that in some cases borders on obnoxiousness. South Island robins, fantails, tomtits, and tiny riflemen (New Zealand's smallest bird) land a few feet away from hikers with little concern. Keas are notorious for trying to get into hiker's backpacks.

New Zealand is home to three native birds of prey: the Kārearea (New Zealand Falcon), the Kāhu (Swamp Harrier), and the Ruru (Morepork). Introduced species include the Little Owl, and several birds of prey, such as the Haast's Eagle, have become extinct. [Source: Google AI]

Introduced bird species include 1) blackbirds (Turdus merula), brought by settlers who missed their familiar calls from England; 2) house sparrows (Passer domesticus), introduced to control insects, but often became a pest by eating crops themselves; and 3) magpie (Gymnorhina tibicen), introduced from Australia to control insect pests on farms. 4) Starlings (Sturnus vulgaris) were introduced from Europe in the 1800s and has become a devastating invasive species, damaging crops and competing with native birds. Mallards (Anas platyrhynchos), an introduced duck, are now the most common ducks in New Zealand. 5) Peacocks (Pavo cristatus) and Pheasant (Phasianus colchicus) were introduced as a game bird for sport.

Helping Endangered Birds in New Zealand

New Zealand has many endangered birds, including well-known species like the Kākāpō, a flightless parrot, and the extremely rare New Zealand fairy tern (tara iti), with fewer than 40 individuals remaining. Other notable threatened birds include the Takahē, a large flightless bird brought back from the brink, and various petrels and albatrosses such as the Chatham Island tāiko and Antipodean wandering albatross. The primary threats to these birds are introduced predators, habitat loss, and human disturbance.

By 1970 only 18 black robins — a species of robin unique to Chatham Island in southern New Zealand survived because of invasive predators and changes in the island's vegetation. The birds lived on a small island, Little Mangere, off the coast of Chatham Island and were having a hard time because much of the island’s vegetation had been destroyed to make a landing pad for helicopters serving lobster-fishing ships. By 1976 only five birds and two females remained and they were declared rarest birds in the world.

In 1976, under conservationist Don Merton, the remaining robins were moved to a forest on nearly Mangee island in a dangerous trap and release operation. The effort was successful but even so by 1978 only five robins survived as old birds died off from old age. To increase their chance of survival the eggs of a robin were taken and placed in the nests of warblers. The technique worked. By 1985, the population had grown to 38. By the late 1990s, there were 150 of these robins. Now there is thriving, self-sustainable population.

Derek Grzelewski wrote in New Zealand Geographic: The concept of island sanctuaries is not new. In 1894, Richard Henry masterminded the transfer of some 750 kiwi and kakapo to Resolution Island, in Fiordland. But he underestimated the enemy. Stoats swam across from the mainland, and 14 years of work was undone. [Source: Derek Grzelewski, New Zealand Geographic. January-March 2000]

Despite that setback, many of our offshore islands have now been turned into refuges for species that elsewhere are either extinct or extremely rare. Some of them were natural sanctuaries on account of their distance from the mainland or their inaccessibility, and only needed to have landings strictly controlled. Others, in the fashion of McLennan’s peninsula, have had to be restored through painstaking trapping of noxious animals and subsequent vigilance against reinvasion. Whatever their past, these islands now serve as insular aviaries, genetic safe houses which offer endangered species an evolutionary second chance, the opportunity of an assisted comeback.

For kiwi, there is no more telling example than Kapiti, a sliver of mountainous, rain-soused land lying off the west coast north of Wellington. Former home of Te Rauparaha, then the site of a whaling station, then a ne’er-do-well sheep farm, in 1897 the island was turned into a wildlife sanctuary. The cleared forest slowly grew back, and the resident caretakers methodically eradicated the vermin. Between 1980 and 1986, 22,500 possums were removed from this 2000 hectares island, and a week before my visit the reserve was officially declared rat-free. Kapiti, now aflutter with birds unseen in most parts of the country.

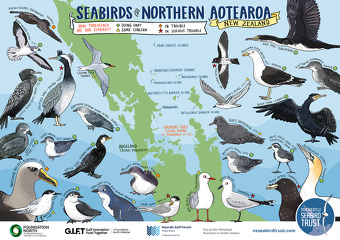

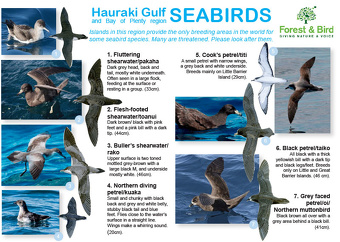

Seabirds in New Zealand

New Zealand has been described as the "seabird capital of the world," with a diverse array of species, including albatrosses, petrels, penguins, gannets, shags, and shearwaters, due to its extensive coastline and surrounding oceanic islands. However, many of these birds are at risk, facing threats from fishing interactions, pollution, habitat loss, and introduced predators.

Muttonbirds(dusky sheerwaters) are found in great numbers on the South Island of New Zealand. Young muttonbirds can weigh twice as much as adults. Humans and some colonies of keas feed on them. Muttonbirding is practiced in New Zealand. See Muttonbirds and Muttonbirding Under BIRDS OF AUSTRALIA: COMMON, UNUSUAL AND ENDANGERED SPECIES ioa.factsanddetails.com

Boobies and gannets catch fish. They fly with fish stored in a crop, a bag that branches internally from their throat. Bar-tailed godwits fly 7,000 miles each year — from Alaska to New Zealand. And they do so without stopping to eat, drink or rest. Kidnappers Cape (15 miles southeast of Napier) is the home of the largest mainland gannet rookery in the world. From October to May, more than 5,200 breeding pairs of these impressive yellow-headed birds and their young can be seen here. Gannets are huge birds. They have eight-foot wingspans and usually nest offshore, but for some unexplained reason they began nesting at Kidnappers Cove 130 years ago. See Napier Under EASTERN NORTH ISLAND OF NEW ZEALAND ioa.factsanddetails.com

Snares Islands is about 200 kilometers (130 miles) south of New Zealand’s South Island. On her visit there, Laura Sessions wrote in Natural History Magazine: The chorus of screeching birds drowned out our rumbling boat motor, and even from several miles away we could smell the acrid white guano that coats much of the Snares’s rocky coasts. During the summer breeding season the Snares, whose entire area totals not much more than one and a quarter square miles, are home to more than six million seabirds — as many as nest along the coasts of Great Britain and Ireland combined. [Source: Laura Sessions, Natural History Magazine, March 2003]

Today in the New Zealand archipelago, such dense seabird colonies persist only on small offshore islands, but at one time much of the coastline of the North and South Islands would have been equally pungent and raucous. New Zealand once supported one of the most diverse seabird faunas in the world; the country was particularly rich in species of petrels. Nowadays those populations have crashed, and many species have been extirpated on the mainland.

Some of the small islands of New Zealand are particularly rich in petrels and shearwaters. David Attenborough wrote: “In New Zealand, shearwaters returning after months at sea to nest in tunnels on the tops of cliffs often find that in their absence their holes have been taken over by primitive lizards, tuataras. Once established, a tuatara becomes the permananet year-round caretaker, keeping the hole clear of blockages so that when the birds return the next season, all they have to do is clear out the nest chamber at the far end. A tuatera will eat shearwater eggs and chicks but considerately it never takes those belonging to its landlord that lie at the far end of the shared tunnel.”

RELATED ARTICLES:

SEA BIRDS: TYPES, MIGRATIONS AND THREATS ioa.factsanddetails.com

SHOREBIRDS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND TYPES ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

SEAGULLS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND ATTACKS ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

TERNS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SPECIES AND ARCTIC TERN MIGRATIONS ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

GANNETS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, NESTING AND DIVING ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

SHEARWATERS AND PETRELS ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

ALBATROSSES: CHARACTERISTICS, NESTING AND THREATS ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

LARGE — WANDERING AND ROYAL —ALBATROSSES: CHARACTERISTICS, SUBSPECIES AND COURTSHIP ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

Impact of Rats on Petrels and Ecosystems in New Zealand

Laura Sessions wrote in Natural History Magazine: A series of inadvertent natural experiments, involving the mix of people, rats, and wildlife on some of New Zealand’s offshore islands, suggests in even greater detail how rats may have affected native fauna over time. For example, on off-shore islands such as Aorangi and Stephens — which became home to Polynesians but never to Pacific rats — petrels, other small birds, invertebrates, frogs, and lizards still abound. Those species have largely disappeared from islands inhabited for long periods by Pacific rats. [Source: Laura Sessions, Natural History Magazine, March 2003]

It is the petrels, though, that most dramatically illustrate the magnitude of the damage that rats probably inflicted in New Zealand. Thirteen species of petrel once bred on the South Island. Today only six still breed there, and only one, Hutton’s shearwater, remains on the island in great numbers. The seven extirpated species certainly disappeared before the Europeans arrived and may have been gone even before the Polynesians settled in New Zealand.

The petrel species that became extinct were precisely the ones whose size and habitat made them most accessible to the Pacific rats. Petrel species that were too big a mouthful for rats persisted on the mainland, even in lowlands, where rats were common. In contrast, the smaller petrel species all disappeared, even where their breeding habitats remained intact. Scarlett’s shearwater, for instance, disappeared from the west coast of the South Island, even though the area retains some of the largest tracts of relatively undisturbed forest in the country. The only small petrel species that survived were the ones that nested on rat-free offshore islands or in cold mountainous regions, inhospitable to subtropical rats. Many of those refuges were later invaded by other, even feistier rat species and by stoats introduced by Europeans.

If rats were responsible for killing off petrels and other native species, what additional effects might their depredations have had? By eliminating huge colonies of seabirds, for instance, Pacific rats could have generated ecological damage far beyond the extinction of particular species. Richard Holdaway, an independent extinction biologist, has drawn particular attention to the amount of organic waste once generated by the seabird colonies — mainly guano, but also lost eggs, dead birds, spilled food, and molted feathers. That waste would have constituted a bonanza of nutrients that flowed continuously from the sea to the land. (Miners on other oceanic islets, such as Nauru and Christmas Island, have come across guano-derived phosphate rock deposits as thick as seventy-five feet.)

The Pacific rat may be the only mammal in the world, besides our own species, that has fundamentally altered an ecosystem on a continental scale. The massive wastes of the seabird colonies on the mainland would have added phosphorus, nitrogen, and carbon to relatively nutrient-poor soils, and lowered the pH of the soil. The birds would also have aerated the soil as they burrowed to shape their nests. The nutrients would have fostered the growth of plants that sustained invertebrates, lizards, birds, bats, and other herbivores. Take the case of Hutton’s shearwater. Holdaway estimates that a remnant colony of these birds on the South Island still supplies more than 1,000 pounds of guano per acre in each breeding season. Extrapolating from that estimate, he maintains that before the appearance of the rats, seabird colonies could have supplied two million tons of fertilizer a year.

The possible implications of the loss of such a nutrient flow are astonishing. Pacific rats have spread to hundreds of islands and have eliminated hundreds of seabird populations. If those changes have equally disrupted hundreds of food webs, it could be that these small rodents have altered island wildlife across the entire Pacific. Holdaway’s next step is to collaborate with investigators from a variety of disciplines to examine the possible connections between petrel disappearances and changes in those food webs. The Pacific rat may be the only mammal in the world, besides our own species, that has fundamentally altered an ecosystem on a continental scale.

Bar-Tailed Godwits — Birds That Fly Nonstop Between Alaska and New Zealand

Every year in September and October bar-tailed godwits fly 11,265 kilometers (7,000 miles) from Alaska to New Zealand — the longest nonstop migration of a land bird in the world— to breed and raise its young. They travel eight to ten days without eating, drinking or resting along the way.Jim Robbins wrote in the New York Times: Tens of thousands of bar-tailed godwits are taking advantage of favorable winds for their annual migration from the mud flats and muskeg of southern Alaska, south across the vast expanse of the Pacific Ocean, to the beaches of New Zealand and eastern Australia.“The more I learn, the more amazing I find them,” said Theunis Piersma, a professor of global flyway ecology at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands and an expert in the endurance physiology of migratory birds. “They are a total evolutionary success.” [Source: Jim Robbins, New York Times, September 20, 2022]

The godwit’s epic flight through pounding rain, high winds and other perils is so extreme, and so far beyond what researchers knew about long-distance bird migration, that it has required new investigations. In a 2022 paper, a group of researchers said the arduous journeys challenge “underlying assumptions of bird physiology, orientation, and behavior,” and listed 11 questions posed by such migrations. Dr. Piersma called the pursuit of answers to these questions “the new ornithology.”The extraordinary nature of what bar-tailed and other migrating birds accomplish has been revealed in the last 15 years or so with improvements to tracking technology, which has given researchers the ability to follow individual birds in real time and in a detailed way along the full length of their journey. “You know where a bird is almost to the meter, you know how high it is, you know what it’s doing, you know its wing-beat frequency,” Dr. Piersma said. “It’s opened a whole new world.

The known distance record for a godwit migration is 13,000 kilometers, or nearly 8,080 miles. It was set last year by an adult male bar-tailed godwit with a tag code of 4BBRW that encountered inclement weather on his way to New Zealand and veered off course to a more distant landing in Australia. He had flapped his wings for 237 hours without stopping when he touched down. The globe-trotting birds are in search of an endless summer, and some 90,000 or so depart Alaska from the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta and environs, where they breed and raise their young. Both Alaska and New Zealand are rich in foods that godwits like, especially the insects in Alaska for newly hatched chicks. And New Zealand has no predatory falcons, while Alaska offers secure habitat.

Sea-faring Polynesian cultures, the scientists wrote in the paper, knew about the migrations long ago and used the birds to assist in navigation. Once they reach New Zealand and the austral summer, the sleek birds — with mottled brown-and-white aerodynamic wings; cinnamon-colored breasts; long, slender beaks; and stilt-like legs — feed on glistening mud flats until March, when they begin their journey back north. The birds are cherished by many New Zealanders. The cathedral at Christchurch began ringing its bells to welcome the birds, but an earthquake in 2011 toppled the bell tower. Another cathedral in the city of Nelson has taken over the task and will ring its bells for the birds later this month. “I tell people try exercising for nine straight days — not stopping, not eating, not drinking — to convey what’s going on here,” said Robert E. Gill Jr., a biologist with the U.S. Geological Survey in Anchorage who has studied the birds in Alaska since 1976. “It stretches the imagination.”

Distances vary, but all told, in a year, the godwits cover some 30,000 kilometers, or nearly 18,720 miles, because they take a less direct route to return north in March. They fly nonstop from New Zealand to China’s Yellow Sea and its rich tidal flats, where they refuel, and then return to Alaska. And they are proficient at the incredibly risky endeavor; the survival rate is more than 90 percent. “It’s not really like a marathon,” said Christopher Guglielmo, an animal physiologist at Western University in London, Ontario, who studies avian endurance physiology. “It’s more like a trip to the moon.”

How Bar-Tailed Godwits Fly Nonstop Between Alaska and New Zealand

Other birds do stay aloft for long periods using a technique called “dynamic soaring,” while godwits power themselves by continuous flapping, which takes far more energy. Jim Robbins wrote in the New York Times: Godwits are avian shape-shifters, endowed with an unusual plasticity. Their internal organs undergo a “strategic restructuring” before departure. The gizzards, kidneys, livers and guts shrink to lighten the load for the trans-Pacific journey. Pectoral muscles grow before takeoff to support the constant flapping the trip requires. They are built for speed, with aerodynamic wings and a missile-shaped body. The only baggage the birds carry is fat, by gobbling up insects, worms and mollusks to double their weight from one to two pounds before embarking on their trip. Because godwits directly use fat to fuel their flight, Dr. Guglielmo in one paper called them “obese super athletes.” [Source: Jim Robbins, New York Times, September 20, 2022]

The journey of these ultra-endurance athletes is made possible by a suite of adaptations. Bird lungs are the most efficient lungs of any vertebrate and help the godwits’ performance in the thin atmosphere of higher altitudes. Bar-tailed godwits in Russia have recently been documented flying at altitudes of three to four miles above ground. No other birds make the same length of powered migration under such punishing conditions, but recent research shows that common swifts stay airborne for virtually all of the 10 months when they’re not breeding or nesting, although they eat and drink during that time.

Wayfinding among the godwits is among the biggest questions recent studies have prompted. “What mechanisms explain birds acting as if they possess a Global Positioning System?” researchers asked. Crossing a nearly featureless Pacific Ocean without navigational cues required an internal “map to define position and a compass to tell direction,” they said. The birds find their way back to the same specific sites at the end of their flight, something they do for each of the 15 or 20 years of their lives. “They have figured out the aerosphere they live in,” Dr. Gill said. “They can predict when to leave and when not to leave, how high to fly, and they know exactly where they are and they know their destination.”The godwits probably rely on several cues for navigation, especially the sun and stars. Some experts believe that they may be able to sense magnetic lines on the planet through a process called quantum entanglement.

The birds also possess an uncanny knack for weather forecasting. “They know what conditions to leave on that will not only provide wind at the start that is favorable, but throughout their entire flight,” Dr. Gill said. “They can piece the puzzle together in terms of what the conditions are in Alaska and between there and Hawaii, between Hawaii and Fiji, and between Fiji and New Zealand. How migration abilities are passed on to the next generation — whether genetically or learned or a combination — is still unknown.

“You study adults, and you think these birds just have it down, they are super robots, they are amazing,” said Jesse Conklin, an independent researcher at the University of Groningen who studies the species. “But when you study young birds, they make mistakes and do all kinds of weird stuff. So they weren’t just born with this routine.” Incredibly, it is possible that three-month-old godwit juveniles fly their nonstop maiden voyage without adult supervision. That has yet to be confirmed.

The energetics of their nonstop migration are also a conundrum. Current models say the birds should conk out after three or four days, yet they fly for more than a week. “We can’t explain the physiology that allows them to do this,” Dr. Guglielmo said. “We know what the energy costs should be from wind tunnel experiments, but when we try to use our models, the energy costs we know they used are much lower.” The birds use half or less of the energy expected.

One answer may be that the birds can lower their metabolic rate on these journeys, burning far less energy than they would for other kinds of flying. “Are they going into a suspended animation state when they are doing these monster flights?” Dr. Guglielmo asked. “I don’t think they are in a normal physiological state when they are doing this,” he said, adding they might enter into a state like something akin to “marathon runners getting into the zone.”

Whether or how the birds sleep is another mystery. It’s been shown that some bird species are capable of unihemispheric sleep, that is, putting one half of their brain to bed while using the other half to fly. Others believe the birds don’t sleep at all but catch up on their rest when they reach New Zealand.

Experts believe the birds communicate frequently, especially about the timing and safety of their trip. Some suggest that the birds gather to create a kind of group mind that helps them make decisions on important matters and take votes on migration, among other things. “It’ll be near hurricane weather and a bird will be stamping around the estuary, calling, trying to get someone to go with her,” Dr. Conklin said. “I watched a bird do this for five days straight. Her clock said go, and everybody else said no. She got outvoted.” She stayed, he said, “but as soon as the weather turned, she was in the first flock out.”

Prehistoric and Extinct Birds in New Zealand

Prehistoric birds in New Zealand include giant penguin, the world’s largest parrot, an eagle with a three-meter wingspan, and 3.6 meter-tall moa birds. The largest eagle ever, the Harpagornis, lived in New Zealand. It had a 2.7-meter (nine-foot) wingspan and weighed 13.5 kilograms (30 pound)s. It's talons were s big as the claws of a tiger. Holes the same size of these as talons have been found in medium-size moas, which indicates that the eagles may have fed on them.

In 2019, scientists announced the discovery of a giant penguin that they estimated stood as tall as a person, based on fossil leg bones discovered by an amateur palaeontologist on New Zealand’s South Island. The new species,Crossvallia waiparensis, was 1.6 meters tall and weighed 80 kilograms — four times more and 40 centimeters taller than the emperor penguin, the largest living penguin. The giant penguin was identified as new to science by a team from Canterbury Museum in Christchurch and Senckenberg natural history museum in Frankfurt after bones were found by Leigh Love, an amateur palaeontologist, at Waipara. [Source: Patrick Barkham, The Guardian, August 14, 2019]

See Separate Articles: NEW ZEALAND PENGUINS: SPECIES, HISTORY, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com ; PENGUINS: CHARACTERISTICS, HISTORY AND SWIMMING ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

Hunted sustainably by the Maori in precontact times, the huia (Heteralocha acutirostris) was driven to extinction in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when its distinctive feathers became fashionable among Westerners in New Zealand and abroad.

In 1894, a cat owned by a lighthouse keeper on a small island killed the last 15 Stephen Island wrens, rendering the species extinct. Predator control efforts today include establishing predator-free islands and managing predator populations to protect vulnerable native species. There are also conservation programs focused on restoring and protect critical habitats.

Herculean Parrot — the Largest Parrot Ever Known

In August 2019, scientists announced that they had fossils of the largest parrot ever recorded — named the Herculean parrot (Heracles inexpectatus) — in New Zealand. The bird stood about one meter (39 inches) tall and weighed up to seven kilograms (15.5 pounds). AFP reported: The remains of a super-sized parrot that stood more than half the height of an average human and roamed the earth 19 million years ago have been discovered in New Zealand. Judging by the size of the leg bones, the bird would have stood about one meter (39 inches) tall and weighed up to seven kilograms (15.5 pounds), according to a report by an international team of palaeontologists published in August 2019 in Biology Letters. “"It could have flown but we're putting our money on it being flightless," Paul Scofield, the senior curator of natural history at Canterbury Museum, told AFP.

“When the bones were found in 2008 no one was certain what they were, and they spent 11 years gathering dust on a shelf until the team looked at them again earlier this year. "The thought they were from a giant parrot did not enter our minds. We thought it could be some type of eagle until we went back and looked at it again," Scofield said.

“The parrot has been named Heracles inexpectatus to reflect its Herculean size and strength — and the unexpected nature of the discovery. "Heracles, as the largest parrot ever, no doubt with a massive parrot beak that could crack wide open anything it fancied, may well have dined on more than conventional parrot foods, perhaps even other parrots," Mike Archer, from the University of New South Wales Palaeontology research centre, said.

“The bird was approximately the size of the giant "dodo" pigeon and twice the size of the critically endangered flightless New Zealand kakapo, previously the largest known parrot. Evidence of the parrot was unearthed in fossils near St Bathans in southern New Zealand, an area that has proved a rich source of fossils from the Miocene period which extends from about five million to 23 million years ago.

“New Zealand, home to the now-extinct flightless bird moa which was up to 3.6 meters tall with neck outstretched, is well known for its giant birds. "But until now, no-one has ever found an extinct giant parrot –- anywhere," associate professor Trevor Worthy from Flinders University said. "We have been excavating these fossil deposits for 20 years, and each year reveals new birds and other animals... no doubt there are many more unexpected species yet to be discovered in this most interesting deposit."

Southern Takahe

The takahe is a plump, tasty ground-dwelling bird hunted by the Maori for food. It was thought to be extinct, with the last known specimens collected in 1898. Careful surveys rediscovered the species in 1948 in an isolated valley in the Murchison Mountains of South Island. There were two species of takahe: the South Island takahē (Porphyrio hochstetteri), which is alive today, and the North Island takahē or mōho (Porphyrio mantelli), which is now extinct. They were formerly considered the same species, but genetic and morphological evidence confirms they were distinct species.

Takahe belong to the coot family and reside in moorlands of mountains. They look like their European relative, the moorhen, but are considerable larger and are more subtlety colored with blue or green plumage and a striped red and white bill. Takahe feed a tussock, a kind of grass that is very low in nutrients. As a result they have to feed almost around the clock and eat only the parts of the grass that are rich in sugar and minerals. Females build their nest below tussock clumps. The greatest threat to takahe today are red deer that also eats tussock but in doing so kills the plants.

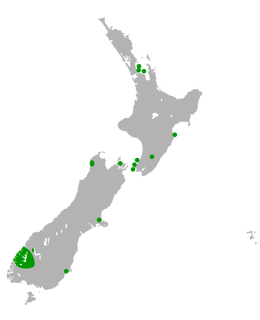

South Island takahe are endemic to New Zealand's South Island, where they reside in alpine tussocks grasslands and sub-alpine shrublands. Following conservation and reintroduction efforts South Island takahe have been introduced to the islands of Tiritiri Matangi, Kapiti, Mana, Maud, and Rarotoka, off the coast of New Zealand's South Island. Island populations live in modified grasslands. [Source: Jose Lara, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

South Island takahe are large, colorful rails with an average length of 63 centimeters (2.1 feet). Rails are a large, cosmopolitan family of small- to medium-sized terrestrial or semi-amphibious birds that exhibit considerable diversity in their forms. South Island takahe have deep to peacock-blue heads, breasts, necks, and shoulders. The wings and back are olive-green and blue. The bill is large and red, as is the shield. South Island takahe also have large, powerful, red legs and feet. Young South Island takahe are deep blue to black at hatching but quickly take on the coloration of adults. There is little sexual dimorphism (differences between males and females). Both sexes are roughly equal in size and look similar but males are a little larger. Their average weight if males is 2.7 kilograms (6 pounds); of female 2.3 kilograms (5pounds).

On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List South Island takahe are listed as Endangered. It is further classified as Nationally Critical under the New Zealand Threat Classification System. As of October 2023, there were about 500 South Island takahe and their growth was around eight percent a year. Threats in the past have included hunting, loss of habitat, and introduced predators. Loss of habitat and introduced predators continue to be threats but they are also threatened by lack of genetic diversity and low fertility rates.

South Island takahe have been the focus of major conservation and reintroduction efforts. Populations have been established on four offshore islands where there are no invasive predators. Captive breeding has been successful. Captive-reared birds have been released into secure mainland sanctuaries and areas such as Kahurangi National Park. The main wild population in the Murchison Mountains is managed to increase its population size and ensure it reaches the area's natural carrying capacity. South Island takahe do not have any native predators. The invasive species that threaten them the most are red deer, and stoats. In captivity South Island takahe have lived up to 20 years. It is estimated they can live between 14 and 20 years in the wild.

Southern Takahe Behavior, Diet and Reproduction

South Island takahe are terricolous (live on the ground), diurnal (active mainly during the daytime), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary) and sedentary (remain in the same area). They are very territorial (defend an area within the home range), most confrontations occur during incubation. Home ranges of South Island takahe vary in size from 1.2 to 4.9 hectares (3 to 15 acres) Densities are highest in moist lowland habitats. [Source: Jose Lara, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

South Island takahe are technically omnivores (eat a variety of things, including plants and animals), primarily herbivores (eat plants or plants parts) and recognize as folivores (eat leaves). Animal foods include insects. Among the plant foods they eat are leaves, roots, tubers, seeds, grains, and nuts. They consume the leaf bases and seeds of native tussock grasses, including broad leafed snow tussock (Chionochloa rigida), mid-ribbed snow tussock (Chionochloa pallens) and curled snow tussock (Chionochloa crassiuscula). They most often take insects when raising young. They also eat rhizomes of native ferns.

South Island takahe are monogamous (having one mate at a time) and engage in seasonal breeding. They breed once a year, following the New Zealand winter, in October. A deep, bowl-shaped nest is constructed of fine grass. The number of eggs laid each season ranges from one to three, with being the norm. The average time to hatching is 30 days. Different survival rates have been reported, but on average only one chick will survive to adulthood.

According to to Animal Diversity Web: Mate selection involves several courtship behaviors. Duetting and neck-pecking, of both sexes, are the most common behaviors. Following courtship, the female solicits the male by positioning her back toward the male, spreading her wings, and putting her head down. Allopreening and copulation is then done by the male.

During the pre-birth stage provisioning is done by females and protecting is done by males and females. During the pre-weaning and pre-independence stages provisioning and protecting are done by males and females.The average fledging age is three months and the average time to independence is one year. South Island takahe pairs, when not incubating eggs, are generally seen in close proximity to each other. In contrast a breeding pair is rarely together during incubation, so it is assumed that one bird is always on the nest. Females incubate significantly more during the day and males more at night. Post-hatch observations suggest that both sexes spend similar amounts of time feeding the young. The young are fed until they are about three months old, at which time they become independent.

Penguins in New Zealand

New Zealand is home to about ten penguin species if you include the ones that nest or show up at is remote island territories, some of which are near Antarctica: 1) New Zealand little penguins, 2) Fiordland penguins (crested penguins), 3) yellow-eyed penguins, 4) Australian little penguins, 5) erect-crested penguins, 6) Snares penguins, 7) rockhopper penguins, 8) Western rockhopper penguins, 9) Eastern rockhopper penguins and 10) royal penguins. There is some debate as whether rockhopper penguins are a single species with several subspecies are is three species. Macaroni penguins have been reported in New Zealand waters. Probably other penguin species enter New Zealand waters too.

The penguins for which New Zealand is best known are New Zealand little penguins (Kororā), yellow-eyed penguins (Hoiho), and Fiordland penguins (Tawaki). New Zealand little penguins are smallest penguin in the world, while yellow-eyed penguins are among the world's rarest and most endangered. Few penguins other than little penguin make it to New Zealand’s North Island. Mostly penguins are found along the coasts of the South Island, on Stewart Island (Rakiura), and on New Zealand’s subantarctic islands further south.

In 2019, scientists announced the discovery of a giant penguin that they estimated stood as tall as a person, based on fossil leg bones discovered by an amateur palaeontologist on New Zealand’s South Island. The new species,Crossvallia waiparensis, was 1.6 meters tall and weighed 80 kilograms — four times more and 40 centimeters taller than the emperor penguin, the largest living penguin. The giant penguin was identified as new to science by a team from Canterbury Museum in Christchurch and Senckenberg natural history museum in Frankfurt after bones were found by Leigh Love, an amateur palaeontologist, at Waipara. [Source: Patrick Barkham, The Guardian, August 14, 2019]

See Separate Article: NEW ZEALAND PENGUINS: SPECIES, HISTORY, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org , National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New Zealand Geographic, New Zealand Tourism, New Zealand Herald, Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various books, websites and other publications

Last updated September 2025