Home | Category: Baleen Whales (Blue, Humpback and Right Whales)

BLUE WHALES

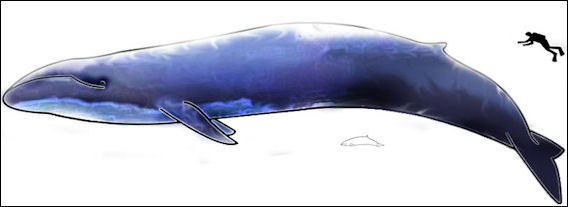

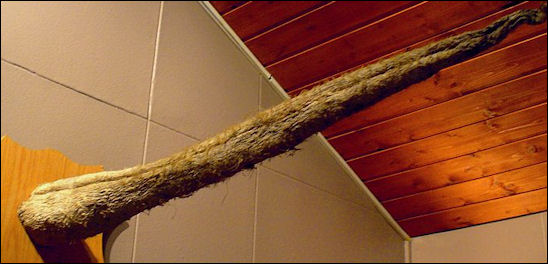

Blue whales (Scientific name: Balaenoptera musculus) are the largest animals that ever lived. They are larger than any dinosaur that ever existed. A large one is equivalent in size to 25 African elephants or all the players in the entire National Football League. The skull is large enough to occupy a room. A male’s penis is eight feet long. A breaching blue whale can reach the height of a five story building with only half of its body coming out of the water. [Source: Kenneth Brower, National Geographic, March 2009]

One field guide described the blue whale’s color as “a light, bluish gray overall, mottled with gray or grayish white.” Kenneth Brower wrote in National Geographic, “but just as often, depending on the light, the back shows as silvery gray or pale tan, Whichever the color, the back always has a glassy shine. When you are up close, you see water sluicing off the vast back, first in rivulets and sheets, and then in a film that flows in lovely, pulsed patterns downhill to the sea.” Underwater they are beautiful turquoise blue.

Blue whales are among Earth's longest-lived animals. Their lifespan is unknown but likely is in excess of 70 years. They become sexually mature around 5 to 15 years. Their average lifespan is estimated at around 80 to 90 years. Scientists have discovered that they can closely estimate the animal’s age by counting the layers of a deceased whale's waxlike earplugs, they can get a close estimate of the animal's age. Blue whales feed almost exclusively on krill, straining huge volumes of ocean water through their baleen plates (which are like the teeth of a comb). Some of the biggest individuals may eat up to 6 tons of krill a day. [Source: NOAA]

Related Articles: CATEGORY: BALEEN WHALES (BLUE, HUMPBACK AND RIGHT WHALES) ioa.factsanddetails.com ; Articles: BLUE WHALE BEHAVIOR, SONG, MATING, FEEDING, SWIMMING AND MIGRATIONS ioa.factsanddetails.com; ENDANGERED BLUE WHALES: HUMANS, THREATS, COMEBACKS AND ORCA ATTACKS ioa.factsanddetails.com ; FIN WHALES: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SUBSPECIES, FEEDING ioa.factsanddetails.com ; WHALES: CHARACTERISTICS, ANATOMY, BLOWHOLES, SIZE ioa.factsanddetails.com ; HISTORY OF WHALES: ORIGIN, EVOLUTION, SPECIES ioa.factsanddetails.com ; WHALE BEHAVIOR, FEEDING, MATING ioa.factsanddetails.com ; WHALE COMMUNICATION AND SENSES ioa.factsanddetails.com ; WHALING: HISTORY, TECHNIQUES ioa.factsanddetails.com ; ENDANGERED WHALES AND HUMANS ioa.factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Fishbase fishbase.se; Encyclopedia of Life eol.org; Smithsonian Oceans Portal ocean.si.edu/ocean-life-ecosystems ; Monterey Bay Aquarium montereybayaquarium.org ; MarineBio marinebio.org/oceans/creatures; Experts on blue whales include Bruce Mate of the Marine Mammal Institute at Oregon State University and John Calambokidis of Cascadia Research in Olympia, Washington; David Mellinger, professor at the Hatfield Marine Science Center at Oregon State University; and Trevor Branch, a fisheries scientist at the University of Washington’s School of Aquatic and Fishery science.

Rorquals, Baleen Whales and Balaenopteridae

Blue whales are rorquals in the family Balaenopteridae. A 2018 analysis estimates that the Balaenopteridae family diverged from other families in between 10.48 and 4.98 million years ago during the late Miocene Period. The 18th century Swedish naturalist Linnaeus derived the genus name from Latin “balanena” (“whale”) and the Greek “pteron” (“fin” or “wing”) The species name “musculus” is the diminutive of Latin word for mouse (“mus”). The full name — “little mouse whale” — appears to have been Linnaeus’s idea of a joke. [Source: Kenneth Brower]

Rorquals are the largest group of baleen whales They comprise ten species in three genera, including blue whales, which can reach 180 tonnes (200 short tons) and fin whales, which reaches 120 tonnes (130 short tons). They smallest member of the family, the northern minke whale, reaches nine tonnes (10 short tons). Rorquals take their name from the French word rorqual, which in turn is derived Old Norse word for whale. Wall Street Journal Wikipedia

Rorquals also including Bryde's, sei and humpback whales. The shape and color of the body, and the size and shape of fins, varies considerably among species. Unlike right whales, roquals have a small dorsal fin and long furrowlike pleats on the throat and breast that expand greatly when the whale has a mouthful of food and water. The pleats allow the whales to take in more food and grow to gargantuan sizes. The pleats — also described as a series of longitudinal grooves and folds of skin — runs from below the mouth back to the navel (except with sei and common minke whale, which have shorter grooves). They "permitting the whales to engorge great mouthfuls of food and water in a single gulp".These "pleated throat grooves" distinguish balaenopterids from other whales.

Longevity in blue whales, and other large cetaceans, is estimated by counting the number of ovarian scars in sexually mature females, changes in the coloration of eye lenses, and counting the number of ridges on baleen plates. According to Animal Diversity Web: The skulls of these mysticetes can be recognized by a combination of the following technical characteristics: the nasals and the nasal processes of the premaxillae extend backward beyond the supraorbital processes of the frontals; the nasals are reduced in size; the frontals are small and barely or not exposed on the dorsal surface; the supraoccipital extends forward beyond the zygomatic process of the squamosal; the rostrum is broad and flat. [Source: Phil Myers, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Blue Whale History

The earliest discovered anatomical modern blue whale is a partial skull fossil found in southern Italy, dating to the Early Pleistocene Period, roughly 1.5–1.25 million years ago. Whole genome sequencing suggests that blue whales are most closely related to sei whales with gray whales as a sister group. This study also found significant gene flow between minke whales and the ancestors of the blue and sei whale. Blue whales also displayed high genetic diversity.

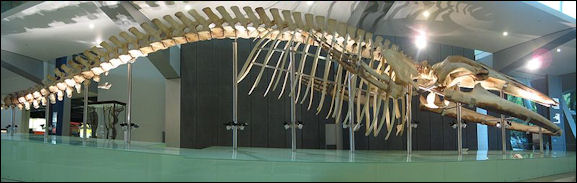

Pygmy blue whale skeleton

There are five currently recognized subspecies of blue whales. The Australian pygmy blue whale diverged during the Last Glacial Maximum. Their more recent divergence has resulted in the subspecies having a relatively low genetic diversity, and New Zealand blue whales have an even lower genetic diversity.

Scientists led by Alistair Evans of Australia’s Monash University, who studied fossil records, worked out that it took 3 million generation for a dolphin-size aquatic mammals to evolve into a blue whales. By comparison sheep-size mammals needed 1.6 million generations to evolve into elephants (or 5 million generations for rabbit-size mammals, 24 million generations form mouse-size mammals. Getting bigger is not just about bones and muscles enlarging; hearts and eyes have to be re-engineered and diet and metabolism change. Whales grew twice as fast as land animals perhaps because water supports added mass better. [Source: National Geographic]

Thanks to their speed and the remoteness of their calving and feeding areas, blue whales survived the go go whaling era of the 18th and 19th centuries but the invention of explosive harpoons and steam-powered catcher boats helped make up for lost time. In the first six decades of the 20th century 360,000 blue whale war killed, including entire populations like the ones around South Georgia Island and off Japan. They were hunted mainly for the oil in their blubber and bones and were highly sought after because of their large size and the fact they were easy to hunt because they stayed near the surface.

Blue Whale Habitats and Populations

Blue whales are found in all oceans except the Arctic Ocean. They live in the tropics as well as among drift ice of Antarctic waters. Blue whales occur mostly in the open ocean far from land but do make appearance near California, Australia, Sri Lanka and other places. Blue generally migrate seasonally between summer feeding grounds and winter breeding grounds, but some evidence suggests that individuals remain in certain areas year-round. Information about distribution and movement varies with location, and migratory routes are not well-known. In general, distribution is driven largely by food requirements — they occur in waters where krill is concentrated. [Source: NOAA]

In the North Atlantic Ocean, their range extends from the subtropics to the Greenland Sea. Blue whales have been sighted in the waters off eastern Canada, in the shelf waters of the eastern United States, and infrequently in the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean. Along the West Coast of the United States, eastern North Pacific blue whales are believed to spend winters off of Mexico and Central America. They likely feed during summer off the U. S. West Coast and, to a lesser extent, in the Gulf of Alaska and central North Pacific waters. Blue whales with young calves have been observed often in the Gulf of California from December through March. Thus, at least some calves may be born in or near the Gulf of California; this area is probably an important calving and nursing area for the species.

In the Pacific Ocean there are two distinct populations, the California group and others that live near Japan and Russia. To figure out which whales were which, the scientists turned to song. "We were trying to separate the catches into east and west, but we didn't know the boundary between the two," said Dr Trevor Branch from the University of Washington. "So we used the current locations of where they sing to figure out the dividing line. Their repetitive calls are different." [Source: Matt McGrath, BBC, September 5, 2014]

In the northern Indian Ocean, there is a "resident" population. Blue whale sightings, strandings, and acoustic detections have been reported from the Gulf of Aden, Arabian Sea, and across the Bay of Bengal. The migratory movements of these whales are largely unknown, but may be driven by oceanographic changes associated with monsoons. In the Southern Hemisphere, Antarctic blue whales occur mainly in relatively high latitude waters south of the "Antarctic Convergence" and close to the ice edge in summer. They generally migrate to middle and low latitudes in winter, although not all whales migrate each year.

Blue Whale Subspecies

Four or five subspecies of blue whale are recognized, some of which are divided into population stocks or "management units". Pygmy blue whales are typically distributed north of the Antarctic Convergence and are most abundant in waters off Australia, Madagascar, and New Zealand. An unnamed subspecies of blue whale is found in the southeastern Pacific Ocean, particularly in the Chiloense Ecoregion, and migrates to lower latitude areas, including the Galapagos Islands and the eastern tropical Pacific. The blue subspecies are. [Source: NOAA]

1) The Northern Indian Ocean subspecies (B. m. indica) ubspecies can be found year-round in the northwestern Indian Ocean, though some individuals have recorded travelling to the Crozet Islands during between summer and fall. Some members of this population live off Sri Lanka the entire year. [Source: Wikipedia]

2) Northern subspecies (B. m. musculus) is generally divided into three populations: A) The North Atlantic population population is mainly documented from New England along eastern Canada to Greenland, particularly in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, during summer though some individuals may remain there all year. They also aggregate near Iceland and have increased their presence in the Norwegian Sea. They are reported to migrate south to the West Indies, the Azores and northwest Africa. B) The Eastern North Pacific population mostly feed off California from summer to fall and then Oregon, Washington State, the Alaska Gyre and Aleutian Islands later in the fall. During winter and spring, blue whales migrate south to the waters of Mexico, mostly the Gulf of California, and the Costa Rica Dome, where they both feed and breed. C) The Central/Western Pacific population is documented around the Kamchatka Peninsula during the summer; some individuals may remain there year-round. They have been recorded wintering in Hawaiian waters, though some can be found in the Gulf of Alaska during fall and early winter.

3) Pygmy blue whale (B. m. brevicauda) is divided into three populations: A) The Madagascar population migrates between the Seychelles and Amirante Islands in the north and the Crozet Islands and Prince Edward Islands in the south were they feed, passing through the Mozambique Channel. B) The Australia-Indonesia population appear to winter off Indonesia and migrate to their summer feeding grounds off the coast of Western Australia, with major concentrations at Perth Canyon and an area stretching from the Great Australian Bight and Bass Strait. C) Eastern Australia/New Zealand population - This stock may reside in the Tasman Sea and the Lau Basin in winter and feed mostly in the South Taranaki Bight and off the coast of eastern North Island. Blue whales have been detected around New Zealand throughout the year.

4) Antarctic subspecies (B. m. intermedia) subspecies includes all populations found around the Antarctic. They have been recorded to travel as far north as eastern tropical Pacific, the central Indian Ocean, and the waters of southwestern Australia and northern New Zealand.

5) Blue whales off the Chilean coast may be a separate subspecies based on geographic separation, genetics, and unique song types. Chilean blue whales may overlap in the Eastern Tropical Pacific with Antarctica blue whales and Eastern North Pacific blue whales. Chilean blue whales are genetically differentiated from Antarctica blue whales and are unlikely to be interbreeding. However, the genetic distinction is less with the Eastern North Pacific blue whale and there may be gene flow between hemispheres.

Blue Whale Size

Blue whales reach weight of 190,000 kilograms (190 tonnes, 418,500 pounds, 209.3 U.S. tons), They reach lengths 33.5 meters (109.91 feet), with their average length being 25 to 27 meters (82 to 88.5 feet), about twice the length of a bus. Sexual dimorphism (differences between males and females) exists: Females are larger than males. [Source: Tanya Dewey and David L. Fox, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) ]

According to the Guinness Book of Records, the longest blue whale was a 33.5-meter (110-foot) -long female caught near the Falkland Islands in 1909. The heaviest one on record was a 90½-foot-long 190-ton female caught in the Southern Ocean in March 1947. By contrast the largest dinosaurs weighed about 100 tons. One hundred ninety tons is almost half a million pounds.

It is not such a surprise that such a large creature is found in the sea. On land its skeleton world have a difficult time carrying that much weight. In the sea, the water takes care of much of weight-bearing duties and bones are not as vital a they are on land. Brower wrote in National Geographic,”Just as an elephant might pick up a little mouse in its trunk. So the elephant, in it turn, might be taken up by a blue whale’s colossal tongue. Had Jonah been injected intravenously, instead of swallowed, he could have swam in the arterial vessels of this whale, boosted along even ten seconds or so by the slow, godlike pulse.” [Source: Kenneth Brower, National Geographic, March 2009]

Blue whale penis, world's largest and longest

Antarctic blue whales are generally larger than other blue whale subspecies. For example, in the North Atlantic and North Pacific, blue whales can grow up to about 27.4 meters (90 feet), but in the Antarctic, they can reach up to about 33.5 meters (110 feet) and weigh more than 150,000 kilograms (150 tonnes, 330,000 pounds, 165 U.S. tons). Like other baleen whales, female blue whales are somewhat larger than males. [Source: NOAA]

The skull of a blue whale measures 5.8 meters (19 feet). The whale's tongue larger than an elephant. The brain of the blue whale weighs seven kilograms (15 pounds) and is 2.3 kilograms (5 pounds) lighter than the brain of the sperm whale. The great whales have the smallest brains of all mammals in relationship to their size. The blue whale's brain represents only 0.005 percent of its total body mass.

Blue Whale Characteristics

Blue whales are members of the roqual family of baleen whales, They can generate 600 horsepower, travel long distances at 20 knots and maintain speed of 12 to 14 miles per hour all day long. They are endothermic (use their metabolism to generate heat and regulate body temperature independent of the temperatures around them) and homoiothermic (warm-blooded, having a constant body temperature, usually higher than the temperature of their surroundings). [Source: Tanya Dewey and David L. Fox, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Blue whales have a long body and generally slender shape. Their mottled blue-gray color appears light blue under water — hence their name, the blue whale. The mottling pattern is variable and can be used to identify individuals. According to Animal Diversity Web: Blue whales are slate to grayish blue and mottled with lighter spots, particularly on the back and shoulders. The undersides often become covered with microorganisms, giving the belly a yellowish tinge. Because of this blue whales are sometimes called "sulphurbottoms". The dorsal fin is short, only about 35 centimeters. The upper jaw is the widest in the genus, and the rostrum is the bluntest. There are 50-90 throat grooves that extend from the chin to just beyond the navel. Blue whale flukes are so large they leave behind a whirl of water that is surprisingly long-lasting. Bruce Mate of the Marine Mammal Institute at Oregon State University told National Geographic, “It’s a measure of how much energy is in the stroke.” A particularly large flukeprint is a sign that the whale is making a deep dive.

Blue whale blowholes The blue whale’s blow hole, Browser wrote, is “a pair of nostrils countersunk atop the tapering mound of the splash guard, built up almost to a kind of nose on the back of the head. Other baleen whales have splash guards too, but not like this. This nose was almost Roman. It seemed disproportionally large, even for the biggest of whales. Its size explained that loud, concussive exhalation — less a breath than a detonation — and its size explained the 30-foot spout. It was a might blow, followed quickly by a mighty inhalation.” When the whale inhales it sucks in enough air to fill a van in a second and a half. The splash guard of the blue whale is big enough for a small child to climb into. [Source: Kenneth Brower, National Geographic, March 2009]

Blues whales are said to have a nasty blowhole smell but not as nasty as that of gray whales. On the smell of a blue whale, Browser wrote, “Now and again the breeze brought a powerful smell of staleness and mold, mixed sometimes with an alarming flatulence...a blast so powerful, so inhumane and malodorous.”

The “defecation trail” left by a blue whale Browser wrote is a “brick red streak of processed krill, more watery than particulate.” Douglas Chadwick, author several books on whales, said “the loose explosions of dung” he witnessed encompassed “great masses of processed krill that turned acres of sea bright pink.”

Blue Whale Heart — A True Work of Art

The heart of the blue whale is the largest known in any animal. According to whalescientists.com: The blue whale’s large muscular heart keeps the blood flowing when the pressure increases in the deep waters. It takes an extremely powerful muscle to pump 10 tonnes of blood through a huge body at such great depths. A slowly contracting aorta (the artery that moves blood to the rest of the body) is what researchers believe is responsible for the blue whale’s heart rate efficiency. Unlike a straightforward open-and-close valve (like us humans), having elastic contractions could allow the blood to flow in between heartbeats. It is an incredibly efficient way to save energy while diving.

The heart of a 24-meter blue whale stranded North Atlantic in 2014 weighed 180 kilograms (400 pounds) and was two meters (6.5 feet) long, including the aorta and other greater vessels, making it slightly smaller than a Smart Car. This particular heart was frozen, pickled and pumped full of silicon and displayed in Canada’s Royal Ontario Museum. The 24-meter blue whale that died in 2014 was one of nine blue whales in the area that perished after being trapped in ice — a tragic loss that resulted in a decrease of Northwest Atlantic blue whale population by 3 percent.

In 2014,Mark Engstrom, the museum’s curator, received a call from the department of fisheries that two blue whale females frozen in ice and then preserved by frigid seawater had washed ashore in Newfoundland. By the time Engstrom arrived it was a stinky tourist attraction and local newspapers ran stories that people should keep their distance lest the whales explode. He and colleague Jacqueline Miller dressed in fisherman waders, smocks and shower cap cut their way through the 24-meter whale,, with a machete. When Miller reached the heart she had to lie on her side and reach beneath it find the arteries that could be severed . Once the heart was disconnected it was raised and moved from the whale with a digger and placed in a large canvas trash bag purchased at a hardware store and squeezed into a freezer. It took two days to thaw and was sent to Germany for “plastination.” [Source: Jennifer Nalewicki, Smithsonian magazine, July 21, 2017]

The heart was the centerpiece of a 2017 exhibition at the Royal Ontario Museum called “Out of the Depths: The Blue Whale Story.” On her effort to extract the heart from the dead whale, Miller, a mammology technician at the museum, told Smithsonian.com. “It took four staff onsite plus myself to push the heart out of the thoracic cavity, through a window created through the ribs and into a dumpster bag.”

After it the heart was frozen it was back to Trenton, Ontario, where it was defrosted. According to Smithsonian.org. The team, along with veterinarians from Lincoln Memorial University’s College of Veterinary Medicine, used anything they could get their hands on — buckets, bottles, even toilet plungers — to seal every last one of the heart’s cavities before pumping a formaldehyde solution into the heart to prevent decomposition. All told, it took 2,800 liters of the preserving liquid to get the job done. It was now ready for the next stop in its journey: Guben, Brandenburg, Germany.

“We chose to plastinate the heart, employing Gunther Von Hagens' company, Gubener Plastinate GmbH,” Miller says. The famed scientist invented plastination, which is the process of preserving a specimen by replacing its water and fat content with different plastics. (If you’ve ever been to a Body Worlds exhibit, you’ve seen plastinated bodies first hand.) “We attempted to dilate (inflate) the heart as [much] as possible, as the goal with fixation is two-fold: arrest further decomposition and then to ‘stiffe' the heart as close to its best natural anatomical conformation as possible,” she says. “For us this was diastole; the condition of the heart when it's fully dilated with blood just before it's ejected with a heart contraction to the body. It’s the moment of largest dimensions for the heart.”

Blue Whale Hearts May Beat Only Twice a Minute During a Dive

Research published in November 2019 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, revealed that the blue heart jump between extremes and may slow to a rate of two beats per minute when it dives really deep. Cara Giaimo wrote in the New York Times: A team of researchers for the first time attached an electrocardiogram tag to a free-diving blue whale to trace its heart rate. They found that the rate ranged as low as two beats per minute and as high as 37. Such numbers paint a picture of an animal frequently pushing its own limits, and suggest that the whale is not only the largest animal ever, but perhaps as large as an animal with a circulatory system can possibly be. [Source: Cara Giaimo, New York Times, November 27, 2019]

“To learn the secrets of the blue whale’s heart, Jeremy Goldbogen, a marine biologist at Stanford University, led a team that attached a noninvasive suction-cup tag to a blue whale in Monterey Bay, California. The tag contains electrodes, a depth measurement sensor and a GPS tracker. It stayed on for eight and a half hours, and recorded data from a number of dives before it detached and floated to the surface. The researchers then tracked it down and reviewed its readings. “Such tags are part of a suite of technologies that make it easier for researchers to study the lives of whales without disturbing them too much. When the tags are attached, a whale likely just feels something akin to a tap on the shoulder, Dr. Goldbogen has said.

The data showed that when this whale descended, its heart rate plummeted, too. At the bottom of the dives, the whale’s heart rate hovered around four to eight beats per minute. At times, it fell all the way down to two. In general, sticking to a slow rhythm while diving lets marine mammals conserve oxygen, so they can stay underwater for longer. But this is “just amazingly low” — far lower than the 11 beats per minute scientists had predicted, said Dr. Goldbogen. And it stays down around 8.5 beats per minute even when the whales are feeding, an energy-intensive process that involves lunging into clouds of krill.

“Dr. Goldbogen credits the blue whale’s flexible aortic arch, which is able to hold about 90 percent of the animals’ blood and slowly release it even when the heart isn’t actively beating.

As a whale climbs back to the surface, its heart rate rises again. By the time it reaches the surface, its blood is moving much more quickly, reoxygenizing in preparation for the next dive. This whale’s heart rate reached a peak of 37 beats per minute. “That’s about as fast as that heart can physically beat,” Dr. Goldbogen said. These rapid shifts happen quite quickly — sometimes within the span of a minute or two — and repeat often. It’s sort of like if you tried moving from a comfortable recliner straight into a set of wind sprints over and over again. “They’re doing this all day long,” said Dr. Goldbogen. “It would be interesting to know how the whale nervous system controls such rapid changes in heart rate,” said Travis Horton, an associate professor at the University of Canterbury in Christchurch, New Zealand.

Image Source: Wikimedia Commons, NOAA, International Whaling Commission, Heart images: Royal Ontario Museum, whalescientists.com

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Wikipedia, National Geographic, Live Science, BBC, Smithsonian, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, Lonely Planet Guides and various books and other publications.

Last Updated May 2023