Home | Category: Nature, Environment, Animals

KAKAPO

Kakapo (Strigops habroptila) are the world’s heaviest and only flightless parrot. Also known as owl parrots and owl-faced parrots, they are ground-dwelling birds that can't fly, but are capable of walking long distances and are agile climbers, clambering and leaping on trees and rocks using their shortened wings for balance. The name "kakapo" means "night parrot" in the Māori language, a reference to the birds' nocturnal habits.[Source: Mindy Weisberger, Live Science July 12, 2025]

Kakapo are vegetarians. Their diet varies with the seasons and includes tubers, fruits, seeds, leaf buds, young plant shoots, fungi and moss. As moas did in the past, kakapo feed primarily on leaves and other plant material without much nutrition and thus need a large body to house the large stomach that processes all this fibrous food. To avoid predators such as harriers and eagles, kakapo became nocturnal. They spend their days in their burrows At night they comes out to feed on shoots of plants and occupy a niche occupied by rabbits.

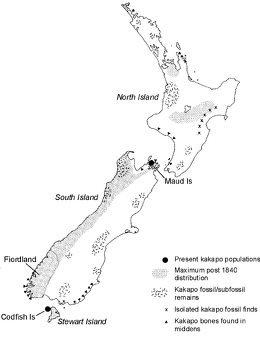

Kakapo are listed as Critically Endangered on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List, meaning they are teetering on the edge of extinction in the wild. There were only 238 individuals left as of August 2025. In 1960, it was believed that kakapo were extinct then some birds were found in Fiordland. Some were trapped and efforts were made to get them to breed but all of those captured turned out to be males. In 1977, a population of about 200 was found in a remote area of Steweart Island. By 1982, some cats somehow reached the valley and killed many birds. Only 86 were left in 2002.[Source: Christina Whiteway, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Kakapo were originally widespread across the North and South Islands of New Zealand, living primarily in forests. The introduction of predators such as cats, dogs and stoats by humans severely depleted the populations, leaving very small relict populations in remote mountains. Remaining populations have been moved onto several offshore islands in a last ditch effort to stave off extinction. Today kakapo are extinct in their original habitat on the North and South Islands of New Zealand and are only found on predator-free Codfish, Little Barrier Islands and Maud, Islands.

Derek Grzelewski encountered a kakapo firsthand during the release of a bird called Sirocco on Codfish Island, located off the southern coast of New Zealand’s South Island. He wrote in Smithsonian magazine: I watched as he climbed out of his box, shuffled up a horizontal branch and stretched his powerful limbs in a ballerina-like posture, using his wings for balance. I reached out my hand slowly, and Sirocco touched it with his stubby beak, then unceremoniously leaped onto my arm as if it were an extension of the branch and climbed up to perch on my shoulder. He put his flat, owl-like face — its wide brown disks around the eyes and a beak nearly obscured by feathery whiskers — next to mine, then stretched out toward a fresh shoot of a fern and began to munch noisily. He reminded me of a Persian cat. [Source: Derek Grzelewski, Smithsonian magazine, October 2002]

RELATED ARTICLES:

KEAS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, PLAYFULNESS, INTELLIGENCE, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

KOKAKOS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

BIRDS OF NEW ZEALAND: SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

KIWIS: EVOLUTION, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

KIWI SPECIES: NORTHERN, SOUTHERN, SPOTTED, LARGEST, SMALLEST ioa.factsanddetails.com

SOUTHERN BROWN KIWI: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

KIWIS, HUMANS AND CONSERVATION ioa.factsanddetails.com

MOAS: HISTORY, CHARACTERISTICS, REPRODUCTION, EXTINCTION, DE-EXTINCTION? ioa.factsanddetails.com

MOA SPECIES: GIANT, SMALL AND HEAVY-FOOTED ONES ioa.factsanddetails.com

Kakapo Characteristics and Diet

Kakapo are very large, rotund parrots, reaching a length of 64 centimeters (2.2 feet) and range in weight from three to four kilograms (6.6 to 8.8 pounds). They have robust but plump bodies, round heads, owl-like faces and strong legs. Kakapo are also one of the longest-lived birds in the world, estimated to reach 90 years. Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present: Females are usually similar to males in coloration but are smaller, more slender and a little greener. The feathers of the male kakapo have a distinctive odor that scientists have described as "sweet and vegetative," and this powerful scent may play a role in males' mating success. [Source: Mindy Weisberger, Live Science July 12, 2025]

The feathers of kakapo on their backs are moss-green, mottled with black chevrons, and dark brown blotches. The top of the tail has similar markings on a green-brown background. The feathers of the throat, breast and under the tail are a soft, mottled, yellow-green color. Immature birds are duller in coloration. The scientific name of kakapo — Strigops habroptila — means "owl-like" — reference to the disc of brown, bristle-like feathers around the ivory colored beak, the eyes, and the ears. Wings are present but , are small and insignificant. The sternum lacks a keel, as there is no need for a place for flight muscles to attach. Kakapo usually holds their body in a horizontal position with the bristle feathers on its face nearly touching the ground. If alarmed or feeling like they must defend themselves, they will stand upright. Kakapos have as much as a half-inch layer of fat under their skin, which helps them stay warm in their cold environment. [Source: Christina Whiteway, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Kakapo are strictly herbivores (eat plants or plants parts) and are also recognized as frugivores (eat fruit) and granivores (eat seeds and grain). Among the plant foods they eat are leaves, roots, green shoots, leaf buds, rhizomes, tubers, seeds, grains, nuts, fruit, pollen. flowers and bryophytes (mosses). They also eat fungus. Their diet varies depending on the season. The digestive system of the kakapo is different from other parrots. Their beak is adapted to grind food up in its mouth, and the gizzard, which is used by most birds to grind their food, is small and degenerate. Unique among land birds, kakapo are capable of storing large amounts of energy as body fat.

Kakapo Behavior

Kakapo can’t fly, even a little bit like chickens. Theyhey are scansorial (good at climbing), terricolous (live on the ground), generally solitary, nocturnal (active at night), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), sedentary (remain in the same area), territorial (defend an area within the home range). Kakapo sense using vision, touch, sound and chemicals usually detected with smell. Kakapo are the only nocturnal parrots in the world. They sleep and rest during the day under rocky outcroppings or in shallow burrows between tree roots, emerging in the evening to forage for food. They maintain large territories and, if another kakapo happens to trespass, the resident kakapo warns it to leave by making a loud "kraak". [Source: Christina Whiteway, Animal Diversity Web (ADW); Live Science |=|]

When they sense danger, kakapos freeze in place, and rely on their mottled emerald-green plumage to camouflage them in their leafy forest habitat. Derek Grzelewski wrote in Smithsonian magazine: “The kakapo has excellent camouflage and engages in a “freeze and blend in” strategy. It’s a strategy that works well against eagle-eyed raptors but does little to safeguard it against tree-climbing predators that hunt by smell. “If the bird only knew its powers, it wouldn’t fall such an easy prey to stoats [a kind of weasel] and ferrets,” Douglas wrote in 1899. “One grasp of his powerful claws would crush either of those animals, but he has no idea of attack or defense.” [Source: Derek Grzelewski, Smithsonian magazine, October 2002]

Kakapo are good at climbing trees, using their wings for balance when moving from branch to branch or moving on the ground and as parachutes when they jump from trees to the ground. Male kakapo are the only parrots that have an inflatable thoracic air sac which they use to produce loud, booming calls, which can be heard from one kilometer to five kilometers away if the wind is right. Males may "boom" continuously up to seven hours a night, for three or four months until they attract a female during the mating season. Agitated kakapo make distinctive shrieks and screams that have been described as being “somewhere between a donkey’s bray and a pig’s squeal”.

Kakapo Mating, Reproduction and Offspring

Kakapo engage in seasonal breeding at irregular intervals every two to four years from December through February or March, when rimu trees produce a large amount of fruit, which are rich in calcium and vitamin D, essential nutrients for egg laying and for nourishing growing chicks. The number of eggs laid each season ranges from one to two. The average time to hatching is 30 days. Young kakapo are altricial, meaning they are relatively underdeveloped at birth. Parental care is provided by females, who build the nest, incubate the eggs and raise the chicks once they have hatched. Nests are on the ground in deep burrows under boulders or between tree roots. When two eggs are laid there can be as much as a month between the first and second egg. The average fledging age is 3.5 months. Females reach sexual or reproductive maturity at 9 to 12 years. [Source: Christina Whiteway, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Kakapo are the only parrot species that engage in lekking — a behavior usually associated with birds-of-paradise. Male kakapo create a makeshift stage — a shallow bowl-shaped depression in the ground called a bowl. They then crouch in their bowl and call for females using two different sounds: a series of low-frequency "booms" that sound like a tuba, punctuated by a high-pitched "ching." Males may boom and ching for eight hours at a stretch, continuing nightly for two or three months. [Source: Mindy Weisberger, Live Science July 12, 2025]

If no females respond male have been known to direct their affections elsewhere. Describing an encounter with an amorous kakapo in 1990, Douglas Adams wrote in his book "Last Chance to See": "When one of the rangers who was working in an area where kakapo were booming happened to leave his hat on the ground," he came back later to find a kakapo attempting to ravish it." Scientists who work with kakapo even built a rubber "ejaculation helmet" to accommodate a kakapo named Sirocco, who was notorious for trying to mate with people's heads. The helmet had a dimpled surface, suitable for collecting sperm for use in artificial insemination.

Kakapo don’t form long-term pair-bonds and because their territories are so large the males and females are often separated by great distances away. The male "lek system" consists bowls described above — which are about 15 centimeters (six inches) wide and 12.5 centimeters (five inches) deep — linked by well worn tracks up to 50 meters long. Males dig and maintain the leks, carefully trimming any vegetation around the bowls and along the tracks. When the bowls were first discovered, along a track volunteer Rod Morris, said it was like “stumbling across the ruins of a tiny, ancient civilization.” The males compete for the "best" bowls. Once the ownership of the bowls is decided the males begin to make their very loud, booming calls. If or when a male is successful in attracting a female to his bowl he does a small courtship dance and the couple mates — marking the end of the male's involvement in reproduction.

The kakapo mating system was worked in the 1970s by conservationist Don Merton. Derek Grzelewsk wrote in Smithsonian magazine: Merton knew that Maori lore told of a whawharua — a secret playground where kakapo gathered to perform mysterious nightly rituals. As he and other researchers examined freshly used bowls and tracks, the Maori story began to appear almost plausible. The area, the biologists concluded, was a kakapo nightclub of sorts, where males would gather to prance, display and make loud vocalizations in hopes of attracting elusive females. Merton and his colleagues learned that the male kakapo, puffed up like a feathered balloon, sits inside his bowl, which serves as a small amphitheater, and sends out a pulsing, low-frequency call, known as booming, which sounds at first like someone blowing across the top of an empty milk bottle. As the calls continue, sometimes for as long as eight hours, the intensity increases until it resembles the blast of a foghorn: Ooooom! Ooooom! The long-wave hum can travel up to three miles (five kilometers).[Source: Derek Grzelewski, Smithsonian magazine, October 2002]

Near Extinct of Kakapos, Humans and Introduced Predators

Kakapo thrived for tens of millions of years across New Zealand, where they had no natural predators. After the arrival of Polynesian people around 800 years ago, their numbers began to drop due at least in part to the introduction of the polynesian rats (kiore, Rattus exulans). Ground-dwelling birds had little natural defense against introduced predatory mammals. Females left their chicks unattended in their burrows for long periods of time, while they foraged for food, making the chicks particularly vulnerable. The main defense of kakapos against threats was to freeze and allow their coloration to blend in with the terrain but kakapo males especially had a strong scent allowing mammal predators that use smell to find prey like rats — and later stoats, weasels, cats and dogs — to find them.

Polynesian settlers ate them and used the feathers to make decorative cloaks and other adornments. There were still lots of them when the first Europeans arrived. “The birds used to be in dozens round the camp, screeching and yelling like a lot of demons, and at times it was impossible to sleep for the noise,” wrote the 19th-century explorer Charlie Douglas. On moonlit nights, Douglas went on, one could shake a tree and kakapo dropped like ripe apples. He also said their firm, fruity white flesh made “very good eating.” [Source: Derek Grzelewski, Smithsonian magazine, October 2002]

The decline of kakapos accelerated when European settlers arrived in numbers and colonized New Zealand in the 1800s. They cleared huge areas for farms, destroying the Kakapo habitat, and introduced domestic cats and stoats, and other predators. Humans also killed kakapo by the thousands for food, and used their feathers for everything from decoration to upholstery stuffing. By the 1900s, deforestation and the introduction of predators, such as cats and stoats, brought kakapo to the edge of extinction. [Source: Christina Whiteway, Animal Diversity Web (ADW); [Source: Mindy Weisberger, Live Science July 12, 2025]

Kakapos bring to mind dodos — birds which lived on the island of Mauritius, near Madagascar and went extinct about 300 years ago. Like dodos, kakapo are a large and solitary ground-dwelling birds too heavy to fly. Both nested and were numerous and longlived but were slow and infrequent breeder, making it difficult for their populations to bounce back once its population was diminished.

Today, kakapo are greatly loved in New Zealand and the public largely supports the efforts and money spent on helping them to survive even though few people have ever seen one in the wild. Local newspapers follow their sex lives, and the government sponsors nationwide contests for schoolchildren to name fledglings. [Source: Derek Grzelewski, Smithsonian magazine, October 2002]

Early Efforts to Rescue Kakapo

Between 1949 and 1973, the New Zealand government wildlife conservation agency launched more than 60 search and rescue expeditions aimed at helping kakpo, mainly to the inaccessible mountains of southwestern South Island, the kakapo’s last stronghold, bastion, a region of large beech forests and cliffs. In the 1960s, five birds were trapped in South Island’s Fiordland National Park, but all died in captivity.

In 1977s, conservationists led by by Don Merton discovered a breeding population of about 200 kakapo on 1,35-square-kilometer (670-square-mile_ Stewart Island, New Zealand’s third largest, about 100 miles south of Fiordland. An all out effort was made to try and rescue them. Sixty-one were caught and moved to four islands cleared of predators but to everyone's dismay nearly all the captured birds were males. After this it was discovered the kakapo males gathered for an elaborate and demanding mating ritual in which they built “bowls” (See Reproduction above), puffed themselves up and made a loud call to attract females. After females choose a mate they went off to a different place to lay their eggs. For their conservation efforts to work they needed to catch some female. Finally in 1980, with the help of a tracking springer spaniel, they found one on Stewart Island. Four other female kakapo, along with their nests and chicks, were discovered in the vicinity soon after.

But not long after that researchers began finding kakapo carcasses. Within two years, the known population of adult kakapo on the island decreased by nearly 70 percent, probably due to feral cats. Stewart Island was not safe. Over a decade starting in 1982, the 61 surviving Stewart Island kakapo were captured and transferred to Little Barrier, Maud and Codfish, three small, nearly predator-free island sanctuaries. There it was discovered that for the both males and females to complete the mating ritual they need to double their weight and needed a lot of food. One reason their numbers had shrunk so low there wasn’t enough for them to eat. It was decided to provide the kakapo with extra food. This was started in 1993 when there were only 19 females left. In 1995, 15 nest were found with 32 eggs but only 13 were fertile and hatched. In 1997, many mating calls were heard. By January 1998 seven young kakapo had successfully been raised.

Stepping Up Efforts to Rescue Kakapo

In 1999, on Maud island, a nest containing three eggs was discovered. “We’ve waited more than 20 years for this nest,” Merton said to his team. “It must succeed!” Derek Grzelewski wrote in , Smithsonian magazine: The nest was perched on a slope so steep that researchers had to cut a winding staircase of 140 steps to reach it. Along with scientist Graeme Elliott and team leader Paul Jansen, Merton organized round-the-clock surveillance of the mother kakapo, whom they named Flossie. Whenever she left the nest at night to forage, a team of researchers moved in. They constructed a three-foot-high wall to prevent any eggs from rolling downhill and a plywood roof over the nest. And they dug a drain above the nest to divert heavy rainwater away from it. Flossie’s movements in and out of the nest set off a door chime that alerted researchers to her comings and goings. A miniature video camera kept an electronic eye on the chicks. Under this intense scrutiny, several broods, totaling 12 chicks in all, grew up over three seasons, raising the overall kakapo population, which had seen several deaths since 1982, to 62 birds. [Source: Derek Grzelewski, Smithsonian magazine, October 2002]

There matters stood until 2001, when researchers on CodfishIsland noticed that the rimu trees there, sources of a nut (encased in a fleshy aril) that they believe somehow triggers kakapo breeding, appeared poised to deliver a bumper crop of fruit. In anticipation of the bounty, they airlifted nine female kakapo from MaudIsland to join 12 females aready on Codfish. “This will be our moment of truth,” said Merton.

While the predictions of rimu plentitude proved accurate, the magnitude of the kakapo baby boom that resulted from it took even Merton by surprise. In 24 nests (four of the females nested twice), the research team found a total of 67 eggs. Once the eggs hatched, researchers got another surprise. Each nestling was eating up to 1,000 rimu nuts every time it was fed, sometimes four times a night. The kakapo mother had to gather rimu nuts furiously, at the pace of some 16 every minute. “This is all the more remarkable,” Merton says, “if you remember that the kakapo is flightless, and that it gathers its food at night, high in the forest canopy.” During the eight-month period between conception and the time when their chicks leave the nest, kakapo mothers were losing as much as a third of their body weight. By summer’s end, 24 new birds, including 15 females, had raised the overall kakapo population to 86. “I think the kakapo have now turned the corner,” Merton said. “They are on the way to recovery.”

Today kakapo conservation, protection and breeding are mainly overseen by the Kākāpō Recovery, a New-Zealand-government-supported organization that combines the efforts of iwi (Maori), rangers, volunteers, scientists and supporters. Among their main concerns are keeping the islands where kakapo live predator-free and making sure the birds have enough food and conditions are ideal for breeding.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org , National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New Zealand Geographic, New Zealand Tourism, New Zealand Herald, Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various books, websites and other publications

Last updated September 2025