Home | Category: Nature, Environment, Animals

NEW ZEALAND PENGUIN SPECIES AND HISTORY

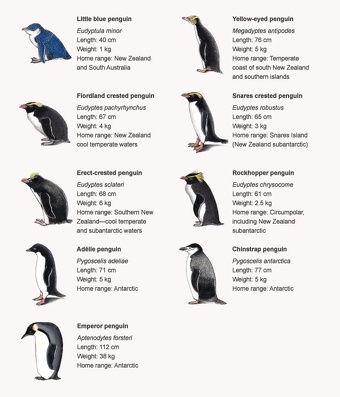

New Zealand is home to about ten penguin species if you include the ones that nest or show up at is remote island territories, some of which are near Antarctica: 1) New Zealand little penguins, 2) Fiordland penguins (crested penguins), 3) yellow-eyed penguins, 4) Australian little penguins, 5) erect-crested penguins, 6) Snares penguins, 7) rockhopper penguins, 8) Western rockhopper penguins, 9) Eastern rockhopper penguins and 10) royal penguins. There is some debate as whether rockhopper penguins are a single species with several subspecies are is three species. Macaroni penguins have been reported in New Zealand waters. Probably other penguin species enter New Zealand waters too.

The penguins for which New Zealand is best known are New Zealand little penguins (Kororā), yellow-eyed penguins (Hoiho), and Fiordland penguins (Tawaki). New Zealand little penguins are smallest penguin in the world, while yellow-eyed penguins are among the world's rarest and most endangered. Few penguins other than little penguin make it to New Zealand’s North Island. Mostly penguins are found along the coasts of the South Island, on Stewart Island (Rakiura), and on New Zealand’s subantarctic islands further south.

In 2019, scientists announced the discovery of a giant penguin that they estimated stood as tall as a person, based on fossil leg bones discovered by an amateur palaeontologist on New Zealand’s South Island. The new species,Crossvallia waiparensis, was 1.6 meters tall and weighed 80 kilograms — four times more and 40 centimeters taller than the emperor penguin, the largest living penguin. The giant penguin was identified as new to science by a team from Canterbury Museum in Christchurch and Senckenberg natural history museum in Frankfurt after bones were found by Leigh Love, an amateur palaeontologist, at Waipara. [Source: Patrick Barkham, The Guardian, August 14, 2019]

Crossvallia waiparensis is thought to have lived in the late Cretaceous and early Paleocene period 66–56 million years ago. It is the fifth pre-historic penguin species described from fossils uncovered at Waipara, where a river cuts into a cliff of greensand sedimentay rock. According to researchers, the penguin’s leg bones suggest its feet played a greater role in swimming than those of modern penguins. The new species is similar to another prehistoric giant penguin, Crossvallia unienwillia, which was identified from a fossilised partial skeleton found in the Cross Valley in Antarctica in 2000.

Many penguin bones found at midden sites — ancient rubbish dumps — indicate that penguins were a popular food among the first human inhabitants of New Zealand, which arrived about A.D. 1250. Today, many commercial operators offer tours for spotting these penguins in their natural habitats. They are mainly in areas with permanent breeding colonies like Dunedin, Ōamaru, and Akaroa. Sites such as Katiki Point Historic Reserve offer viewing opportunities for yellow-eyed penguins. Be cautious of little penguins on coastal roads, as they are often hit by motor vehicles.

RELATED ARTICLES:

PENGUINS: CHARACTERISTICS, HISTORY AND SWIMMING ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

ENDANGERED PENGUINS: DECLINING NUMBERS, THREATS ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

PENGUIN BEHAVIOR, SEXUALITY AND YOUNG ioa.factsanddetails.com

EMPEROR PENGUINS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SWIMMING ioa.factsanddetails.com

Little Penguins

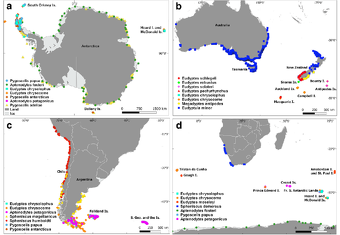

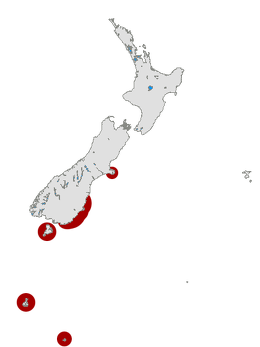

Penguin species nesting sites: a) Antarctica, b) Australia, New Zealand, surrounding sub-Antarctic islands, c) South America, d) South Africa, surrounding sub-Antarctic islands; New Zealand species: royal penguin (Eudyptes schlegeli), Snares Penguin (Eudyptula robustus), Erect-crested Penguin (Eudyptula sclateri), Fiordland Penguin (Eudyptula pachyrhynchus), Macaroni Penguin (Eudyptes chrysolophus), Southern Rockhopper: (Eudyptes chrysocome), yellow-eyed penguin (Megadyptes antipodes), little penguin (Eudyptula minor)

Little penguins are the smallest species of penguin. Also known as fairy penguin, little blue penguin, or blue penguin, owing to its slate-blue plumage, are stand about 30 centimeters (one foot) tall and found along the southern coasts of Australia, from Western Australia to New South Wales, and also breeds in Tasmania and parts of New Zealand, including the Otago region. They were widely known as fairy penguins in Australia, but the name was deemed politically incorrect. The Maori call them kororā.

There are considered to be two species of little penguin: the Australian Little Penguin (Eudyptula novaehollandiae) and the New Zealand Little Penguin (Eudyptula minor), although some authorities still classify them as one species with subspecies. This division is based on mitochondrial DNA analysis, which revealed significant genetic differences between the Australian and New Zealand populations. Australian little penguin are the only penguin species that breeds on the Australian mainland. There are five others that do so in New Zealand.

New Zealand little penguins are found along the entire New Zealand coastline and in the Chatham Islands. They are nocturnal on land, nesting in burrows. They dive for food throughout the day and returns to burrows on the shore at dusk, making them the only nocturnal penguin species on land. Their feathers are dense in melanosomes, which increase water resistance and give them their unique blue color. Little penguins on average live around six years. One banded individual was recaptured at the age of 25 years and eight months old.

See Separate Article: LITTLE PENGUINS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

Yellow-Eyed Penguins

Yellow-eyed penguins (Megadyptes antipodes) are also known as hoiho (their Maori name). Endemic to New Zealand and the sole extant species in the genus Megadyptes, they were previously thought to be closely related to little penguins but molecular research revealed they are more closely related to penguins of the genus Eudyptes (crested penguins). Yellow-eyed penguin are one the shyest and most privacy-loving of all penguins, often seeking refuge in forests when on land. Like most penguins they mainly eat fish.

Yellow-eyed penguins are found in the southern regions of New Zealand, including the South Island, the Otago Peninsula in the South Island, Stewart Island, and a few other islands in the same area. These penguins are not migratory (make seasonal movements between regions, such as between breeding and wintering grounds) and stay in this range just described year round. Yellow-eyed penguins live and nest on shores covered in coastal forest. They hunt in the seas off of New Zealand and the islands they inhabit. [Source: William Wardell, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Studies indicate that yellow-eyed penguin are relatively recent immigrant to New Zealand, arriving about 500 years ago when Waitaha penguins went extinct (see the bottom of the article). Waitaha penguins are believed to have been closely related to yellow-eyed penguins, but smaller. The yellow-eyed penguin filled a niche after the Waitaha became extinct following the arrival of Polynesian settlers between 1300 and 1500 AD. Otago University zoologist Dr Phil Seddon. Seddon said the early yellow-eyed penguin population escaped the same fate because of a unique set of circumstances, including a shift away from the coast by humans, and a growing awareness of the need to preserve natural resources. "You don't hear about yellow-eyed penguins in Maori culture the same way that you do about huia and kiwi for example, so they may have kept a low profile."

Yellow-eyed penguins are an endangered species. Some regard them as the most endangered penguin species. There are estimated to be 7,000 of them and they are the focus of an extensive conservation effort in New Zealand. It is estimated that their population declined by 75 percent over a 15 year period in the late 1990s and early 2000s. On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List they are listed as Endangered; on the U.S. Federal List they are classified as Threatened. There are various conservation efforts in place to help yellow-eyed , including penguin reserves, such as privately-owned Penguin Place in Dunedin, New Zealand, which charges a fee for tours, with much of the money going to conservation efforts to help the penguins. Another conservation effort is the Yellow-eyed Penguin Trust. [Source: William Wardell, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

The main threats to yellow-eyed penguins are disease, overfishing in the seas where they hunt and deforestation on the coast of New Zealand. In spring 2004, a previously undescribed disease — diphtheritic stomatitis — killed off 60 percent of yellow-eyed penguin chicks on the Otago Peninsula and in North Otago. The disease has been linked to an infection of Corynebacterium, a genus of bacteria that also causes diphtheria in humans. A similar oubreak occurred on Stewart Island. Treatment of chicks in hospital has proven successful with 88 percent of 41 chicks treated in 2022 surviving. [Source: Wikipedia]

Yellow-Eyed Penguin Characteristics

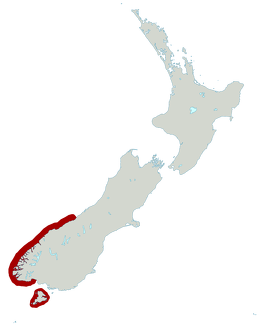

range of yellow-eyed penguins: North to South: Banks Peninsula, Otago Coast, Stewart Island, Auckland Islands, Campbell Islands

Yellow-eyed penguins are relatively large penguins and the largest penguin species that does not live in the Antarctic. They range in weight from five to eight kilograms (11 to 17.6 pounds) and stand 56 to 78 centimeters (22 to 30.7 inches) tall, with their average height being 70 centimeters (27.56 inches). Their height and length are approximately the same thing. Yellow-eyed penguins are endothermic (use their metabolism to generate heat and regulate body temperature independent of the temperatures around them). [Source: William Wardell, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

The defining characteristic of yellow-eyed penguins is their yellow eyes. The main difference between adult and juvenile penguins is the presence of yellow plumage on the adult's heads. Yellow feathers are not present on juvenile penguins until they molt, around the age of one. The average lifespan of yellow-eyed penguins is 23 years. Male yellow-eyed penguins typically live longer than females. Predation does not play a big role in determining their lifespan. One of the main factors that influences lifespan is the amount of breeding, with those who do not or cannot breed typically living longer than those that do breed.

Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present: Sexes are colored or patterned differently with the male being more colorful. Males have bright yellow colorations on their head produced by the pigmentation of their head feathers. Carotenoids (fat-soluble organic pigments) are responsible for the bright yellow coloration of the male's head. It has been hypothesized that bright yellow colorations indicate good health and good genes to a potential mate.

Yellow-Eyed Penguin Behavior, Communication, Diet, Predators

Yellow-eyed penguins are natatorial (equipped for swimming), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary) and sedentary (remain in the same area). They usually stay in one area, except when hunting and are not a colonial (live together in groups or in close proximity to each other) like many other penguin species. These birds typically stay on the shore. When they do forage, they only travel about seven to 13 kilometers offshore and they hunt off the continental shelf. [Source: William Wardell, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Yellow-eyed penguins communicate with sound and sense using vision, touch, sound and chemicals usually detected with smell. Potential mates with shrill calls. Their nest sites are usually well hidden, this call is used by mates to find each other, as well as by juveniles to find their parents. They are pretty solitary for penguins do not have much contact with other penguins and are easily startled by humans.

Yellow-eyed penguins are carnivores (eat meat or animal parts) and primarily piscivores (eat fish). Their foods include fish, eggs. mollusks and aquatic crustaceans and their consists mostly of small prey — fish or sea creatures that juveniles or species whose adults are small. Among the fish species they eat are opalfish (Hemerocoetes monopterygius), red cods (Pseudophycis bachus), blue cods (Parapercis colias), silversides (Argentina elongata) and spats (Sprattus antipodum). Among the mollusks and crustaceans they eat are Nototodarus sloani and Nyctiphanes australis. Most of their hunting occurs off the coast at the edge of the continental shelf. Their foraging behavior depends on the breeding season. Penguins that have not bred successfully travelled greater distances to hunt. Their trips off shore are relatively shorter than trips of other penguins of a similar size.

The main known predators of yellow-eyed penguins are New Zealand sea lions at sea and introduced ferrets, feral house cats and domestic dogs on land. Ferrets and house cats usually take eggs and young. Dogs are capable of killing adults. Yellow-eyed penguins do not really have defenses against terrestrial mammals as they were not present when these penguins evolved and arrived relatively recently on New Zealand.

Yellow-Eyed Penguin Mating, Reproduction and Offspring

Yellow-eyed penguins are monogamous (have one mate at a time) and breed annually from August through March. The number of eggs laid each season is usually two. The time to hatching ranges from 38 to 54 days, with the average being 43 days. The fledging age ranges from three to 4.5 months, with the average being 3.5 months. Females reach sexual maturity at two to three years. Males reach sexual maturity at three to four years. Yellow-eyed penguins are relatively close relatives with crested penguins and have similar reproductive behavior, [Source: William Wardell, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Yellow-eyed penguins nesting behavior influences their social structure and interactions. Nesting sites are generally very large and isolated. Research suggest that the more isolated the nesting site, the more effective breeding is. Most of their nesting sites are under the cover of surrounding plants in a coastal forest. These isolated nests prevent yellow-eyed penguins from being colonial like many other penguins.

Male and females yellow-eyed penguins partner up each 28-week breeding season. During this time, penguins they build a nest where the eggs are laid and incubated. The two eggs are laid at the same time, usually in September and October. Unlike many other penguin species, yellow-eyed penguins lay two similarly sized eggs that both yield viable offspring. In contrast, many penguin species lay eggs of two different sizes. In the case of yellow-eyed penguin since both eggs yield viable offspring, they must incubate both. This is likely due to the amount of the hormone prolactin that is secreted.

Yellow-eyed penguins eggs to typically hatch in November. Parental care is provided by both males and females. Both males and females incubate the eggs and protect the young and provide food for them. This period of brooding usually takes about six weeks. Parents take turn guarding the newly hatched penguins and hunting for food. After the six week brooding period, protection by parents is less but provisioning is increased until juveniles fledge and fend for themselves.

Snares Penguins

Snares penguins (Eudyptes robustus) are also known as Snares crested penguins and Snares Islands penguins. The Maori call them Pokotiwha. Endemic to New Zealand, they breed on the Snares Islands, a group of islands off the southern coast of the South Island. The average lifespan of the Snares penguin is 15 to 20 years if the survive the first couple of years. The mortality rate among chicks is 50 to 90 percent, with most deaths occurring during the first three weeks after chicks hatch.[Source: Angelina Fisher-Hewett, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

The Snares Islands is a group of uninhabited islands lying about 200 kilometers (120 miles) south of New Zealand's South Island and to the south-southwest of Stewart Island. Wet subantarctic conditions prevail. The Snares penguin's habitat is made up of rocky shores and forest. island. The penguins can be found on bare rocks, open areas surround by tussock grass, forest, or under the canopies of shrubs such as Olearia iyallii, Brachyglottis stewartiae and Hebe elliptica, which provide a sturdy nesting ground for the penguins. The forest provide items to build nests such as twigs, pebbles, peat, leaves, and grass. Snares penguins are not a migratory and stay on or close to the Snares Islands, which are part of the New Zealand Sub-Antarctic Islands UNESCO World Heritage Site. This means among other things that Snares penguins are protected by international conservation laws that forbid hunting of Snares penguins and the collection of their eggs.

On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List, Snares penguins are listed as Vulnerable mainly due to the small size of their island range and its vulnerability to some event such as a disease outbreak or the disappearance of prey fish. For the most part there are few threats that affect Snares penguins as they live in such an isolated place. Threats they do face include commercial fisheries, overfishing, climate change, oceanographic changes, and oil spills. There are no major introduced predators on the Snares Island but there is always the possibility an accident might occur and some rats or cats might be introduced. There is a lot of squid around the islands that attracts commercial fisheries and this could affect the penguins. There is limited Snares penguins ecotourism. The penguins can only viewed from afar. Laws that that protect the penguins prohibit boats from docking on the island. The penguins are viewed from ships from October to February. |=|

Snares Penguin Characteristics, Diet and Predators

Snares penguins range in weight from 2.5 to four kilograms (5.5 to 8.8 pounds) and range in length from 50 to 70 centimeters (19.7 to 27.5 inches). Their height is approximately the same as their length. Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present: Males are larger than females. Their bills are also larger than thos of females. On average males weigh 3.4 kilograms (7.4 pounds) while female on average weigh 2.8 kilograms (6.2 pounds). [Source: Angelina Fisher-Hewett, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Snares penguins are yellow-crested penguins. They have dark blue-black upper parts and white underparts. Their most distinctive characteristic is a bright yellow eyebrow-stripe extends over the eye to form a drooping, bushy crest. The bill of the penguin is red-brown, with a bare pink base that distinguishes Snares penguins from their closest relatives Fiordland penguins.

Snares penguins are carnivores (eat meat or animal parts) and also recognized as piscivores (eat fish) and molluscivores (eat molluscs). Based examinations of the penguins’ stomach and the presence of fish ear bones, custacean shells and cephalopod beaks, the diet of Snares penguins consist of crustaceans, fish, and cephalopods, with the main food source being krill (Nyctiphanes australis).

There are only three known predators of Snares penguin:Hooker's sea lions, brown skuas and giant petrels. Hooker's sea lions mainly consume mainly adult penguins. Eggs and small chicks are preyed on by the skuas and petrels. On land Snares penguin can display very aggressive behavior to defend themselves and their chicks and can produce calls that warn other penguins.

Snares Penguin Behavior

Snares penguins are terricolous (live on the ground), natatorial (equipped for swimming), diurnal (active mainly during the daytime), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), migratory (make seasonal movements between regions, such as between breeding and wintering grounds), territorial (defend an area within the home range), social (associates with others of its species; forms social groups) and colonial (live together in groups or in close proximity to each other). [Source:Angelina Fisher-Hewett, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Angelina Fisher-Hewett wrote in Animal Diversity Web: Typical behaviors by these penguins are huddling and preening. Huddling is what the penguins do to minimize loss of heat in their bodies. Preening is when the penguins gather oil from their preening gland on the rump and applies it to their feathers to maintain the feathers and keep water from penetrating through. |Aggressive behavior is shown when there is an intruder. The Snares penguin will do a point and gape; here the penguin will point its bill at an intruder and open its bill, then will proceed to growl to warn the intruder that it is entering a territory. This penguin also can charge the intruder with its wing extended completely and its beak open. |=|

Snares penguins communicate with vision and sound and sense using vision, touch, sound and chemicals usually detected with smell. Mated pairs and potential mates communicate via visual displays (initially by the male). The male penguin will stand up straight with its wings extended, repeatedly pumping its chest. The mated pairs can respond to one another visually by bowing, or acoustically by trumpeting. Most aggressive encounters are visual displays and chases, with very little tactile responses. |=|

Snares Penguin Mating, Reproduction and Offspring

Snares penguins are monogamous (have one mate at a time), often for life. If one of the pair dies,the surviving penguin seeks a new mate. Studies have indicated that the second monogamous pair has less success reproducing over time. Reproductive success is also higher among pairs that reunite in successive seasons rather than newly-established pairs. Snares penguins engage in seasonal breeding — once a year from September to February. The number of eggs laid each season ranges from one to two, usually two, with only of the hatchlings surviving. The eggs are laid late September into early October with the first egg being smaller and hatching four to six days before the second, larger egg. The time to hatching ranges from 31 to 54 days, with the fledging age ranging from four to 16 weeks. The average fledging age is 11 weeks and the age in which they become independent ranges from two to 72 months. Females and males reach sexual maturity at four to eight years. [Source: Angelina Fisher-Hewett, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

During the first three weeks of the breeding season, males show up at the breeding island, a week before the females arrive. Males try to attract the attention females by standing upright with their wings extended and repeatedly pumping their chest. This behavior is called an ecstatic display. Bowing and trumpeting occurs between pairs. Bowing occurs when males return to the nest, and are performed mutually by males and females. Trumpeting occurs when males are away for an extended period.

Parental care is provided by both females and males, who build the nest together from peat, twigs, stones, and bones and line it with mud. Pre-birth provisioning is done by males and females and protecting is done by males. The eggs are incubated by both males and females with females doing the bulk of the work while males forage. When the males return they incubate the eggs while females forage but they make sure to return before the eggs hatch. When pairs that have been separated during foraging bouts are reunited, they greet each other with trumpeting and bowing.

Newborn chicks are are altricial, meaning they are relatively underdeveloped at birth. During the pre-weaning stage provisioning and protecting are done by females and males. During the guard stage after hatching male penguins “guard” the chicks while females forage for food to feed them, returning to the nest every day. Two chicks often are born but generally onl one survive due at least part to the difference in eggs size. The second egg weighs an average of 130.4 grams (5.7 ounces), and the first egg averages 102.1 grams (4.7 ounces). The chick that does not survive usually does not make it past the incubation or guard stage.

After the guard stage the chick creche — explore with other chicks in small groups until the chicks reach 11 weeks old. At 11 weeks old they are considered fledglings. During the fledging period juveniles molt, losing their baby fluff, and gaining adult feathers that protect them from the cold. At this time juveniles become active, independent and explore their surroundings more. There is an extended period of juvenile learning. While they are becoming independent they learn to hunt and swim.

Studies have shown that chicks are more responsive to their mother’s calls than any other adult penguins. According to Animal Diversity Web: Calls were more effective with the chicks than visual signals, and their nest were used as a meeting place during the creche stage. The creche stage is where a small group of chicks ranging from three to 20 chicks group together unattended while both parents forage at sea. When the parents return the chicks recognized their mother’s calls not only at the meeting site, but from any other site as well. |=|

Fiordland Penguins

Fiordland penguins (Eudyptes pachyrhynchus) are also known as Fiordland crested penguins. The Maori call them tawaki or pokotiwha. Possessing a yellow stripe that runs across the top of their head and a feathery yellow tuft that come out of the stripe, they are crested penguins endemic to New Zealand, breeding along the southwestern coasts of New Zealand's South Island as well as on Stewart Island (Rakiura) and its outlying islands such as Solander. Because they originally ranged beyond Fiordland, they are sometimes referred to as the New Zealand crested penguin. They are is occasionally found in Australia, usually Tasmania.

Fiordland penguins are open-ocean penguins. They spend the winter and up to 75 percent of their lives in the ocean. They spend so much time there barnacles often attach themselves to the penguins’ tail. The other 25 percent of the Fiordland penguins’ life is spent on secluded land areas during the breeding season. These penguins spend several months at sea at a time and pairs nest alone or in small scattered groups on densely populated slopes. The nests are sheltered from rainfall and storms. Fiordland penguins are sometimes confused with the Snares penguins. The two species look nearly identical but Fiordland penguins have white markings on their cheeks, and the Snares penguins do not. The two penguins also have different lifestyles and breeding cycles. Even though they both occupy the New Zealand area, they are reproductively isolated and do not interbreed. [Source: Tricia Braswell, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Fiordland penguins range in weight from two to five kilograms grams (4.4 to 11 pounds) and range in length (and height) from 40 to 55 centimeters (15.7 to 21 inches). Sometimes called thick-billed penguins, they have a black head and body, with the exception of a white front and white markings on the cheeks. Their crest is composed of brilliant yellow feathers which are visible at the base of the bill and extend over the eyes. Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is not present: Both sexes are roughly equal in size and look similar. Chicks have gray-brown backs with white fronts. |=|

Fiordland penguins are classified as near threatened on the IUCN Red List. Their status was changed from vulnerable to endangered by the Department of Conservation in New Zealand in 2013. There are a estimated 2,500 to 3,000 breeding pairs of Fiordland penguins left. In the mid 1980s, it was estimated that there were 5,000 to 10,000 breeding pairs of Fiordland Penguins. Surveys in the 1990s counted 2,500 pairs, though this was likely an underestimate. Based on historic trends, the population is probably in decline. The main threats are introduced predators such dogs, cats, rats, and especially introduced stoats (weasels). Their eggs are vulnerable to predation from dogs, skuas, stoats and weka (giant insects). They are also vulnerable to human disturbance, fleeing nests and leaving chicks exposed to predators. Natural predators at sea include fur seals and sharks. [Source: Wikipedia]

Fiordland Penguin Behavior, Diet and Reproduction and Offspring

Fiordland penguins are motile (move around as opposed to being stationary) and reside in the ocean during the winter, staying there alone for many months. In July, they come ashore and spend much of their time on land during the breeding season. While on land, these shy and timid penguins are (nocturnal (active at night) and hide at their nesting site, avoiding outsiders and threats the best they can. They sense using vision, touch, sound and chemicals usually detected with smell. [Source: Tricia Braswell, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Fiordland penguins mainly feed in coastal waters, particularly during the breeding season, but do venture far out to sea. Their diet consists mainly of cephalopods (85 percent, primarily arrow squid, Nototodarus sloanii), followed by crustaceans (13 percent, primarily krill, Nyctiphanes australis) and fish (two percent, mainly red cod and Blue grenadier (hoki)). The the importance of cephalopods might be overstated. Prey taken seems to vary between Codfish Island and northern Fiordland. [Source: Wikipedia]

Fiordland penguins nest in loose colonies. They locate their nests fairly far inland from the coast, with some nest sites up to 100 meters above sea level. Nests are located seperate and out of sight of ther nests. Unlike many of other crested penguins, Fiordlands do not nest in the open. Their nests are in caves, under logs, at the base of trees, and under bushes (particularly away from sand flies). |=|

Fiordland males show up at the nesting sites in July, two weeks before females. Shortly after the females arrive they mate. Soon after that, females lay two pale-green eggs, which incubate for four to six weeks. It is unusual for both of the eggs to hatch. If they they do, the parents are unable to forage enough food for both chicks, usually resulting is the death of the smaller sibling. During the first two to three weeks of the chicks life, during the guard period, males stay and guard the nest while female gather food and regurgitate it for the young. After couple of weeks both parents collect food, leaving the chicks either alone or in loose creches (breeding groups). About 75 days after hatching, Fiordland chicks moult and go to sea with their parents.

New Penguin Species Discovered in New Zealand 500 Years after It Went Extinct

In November 2008, researchers studying a rare and endangered species of penguin announced they uncovered a previously unknown species went extinct about 500 years ago. Associated Press reported: The research suggests that the first humans in New Zealand hunted the newly found Waitaha penguin to extinction by 1500, about 250 years after their arrival on the islands. But the loss of the Waitaha allowed another kind of penguin to thrive — the yellow-eyed species that now also faces extinction, Philip Seddon of Otago University, a co-author of the study, said. [Source: Ray Lilley, Associated Press, November 19, 2008]

The team was testing DNA from the bones of prehistoric modern yellow-eyed penguins for genetic changes associated with human settlement when it found some bones that were older — and had different DNA. Tests on the older bones "lead us to describe a new penguin species that became extinct only a few hundred years ago," the team reported in a paper in the biological research journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences.

Polynesian settlers came to New Zealand around 1250 and are known to have hunted species such as the large, flightless moa bird to extinction. Seddon said dating techniques used on bones pulled from old Maori trash pits revealed a gap in time between the disappearance of the Waitaha and the arrival of the yellow-eyed penguin. The gap indicates the extinction of the older bird created the opportunity for the newer to colonize New Zealand's main islands around 500 years ago, said Sanne Boessenkool, an Otago University doctoral student who led the team of researchers, including some from Australia's Adelaide University and New Zealand's Canterbury Museum.

Competition between the two penguin species may have previously prevented the yellow-eyed penguin from expanding north, the researchers noted. David Penny of New Zealand's Massey University, said the Waitaha was an example of another native species that was unable to adapt to a human presence. "In addition, it is vitally important to know how species, such as the yellow-eyed penguin, are able to respond to new opportunities," he said. "It is becoming apparent that some species can respond to things like climate change, and others cannot. The more we know, the more we can help."

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org , National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New Zealand Geographic, New Zealand Tourism, New Zealand Herald, Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various books, websites and other publications

Last updated August 2025