Home | Category: Nature, Environment, Animals

TUATARAS

Tuataras are found on islands near the New Zealand mainland. They are 60 centimeters (two feet) long and look like lizards but actually belongs to a separate order of reptiles (Rhynchocephalia) that thrived between 70 and 200 million years ago. There are two subspecies of tuatara: the common tuatara (Sphenodon punctatus punctatus) and the Brothers Island tuatara (Sphenodon punctatus guntheri). The Brothers Island tuatara was once believed to be extinct but was rediscovered on North Brother Island and has since been reintroduced to other islands. While the two species look similar, they are genetically distinct.

When the tuatara was discovered by Europeans in the 1830s, it was described as a lizard, but later it was classified as a different order of reptiles because it had distinct non-lizard features such as an upper jaw that overhangs the lower jaw to form a small, beak-like point (the same features have been in fossils of tuatara-like reptiles from the dinosaur era).

Tuataras have olive-colored skin and yellowish markings. They are lethargic creatures that spend much of their time in sea bird burrows, emerging from these burrow at night to feed on insects, worms and small fish. Tuataras reproduce very slowly. They take 10 to 20 years to reach sexual maturity, a long time for a reptile. Female tuataras lay eggs once every four of five years, a long time, and the eggs take 12 to 15 months to incubate, an incredibly long time.

Often featured in Maori legends and art, tuataras were found throughout New Zealand but were nearly wiped out by introduced rats and dogs. Today they are making a comeback thanks to a recovery programs at Victoria University in Wellington, where scientist have learned how to incubate tuatara eggs and raise the small reptiles in a laboratory. Scientists have released the young tuataras on islands where rats have been eradicated. About 400 “Sphenodon guntheri”, the rarer of the two tuatara species, live on ten-acre North Brother Island.

Evolution of Tuataras

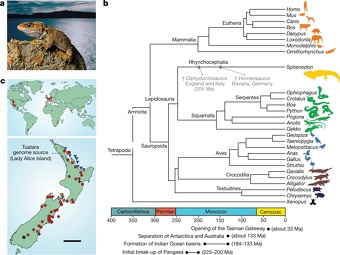

Tuataras are the only living descendents of the Rhynchocephalia order of reptiles. There were a considerable number of Rhynchocephalians species during the Triassic period (252 million years ago to 201 million years ago). By 60 million years ago, in the Late Cretaceous Period (100 million to 66 million years ago), all Rhynchocephalia except for the tuatara appear to have been extinct. [Source: Bruce Musico, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Tuatara belongs to a group of reptiles known as sphenodontians, which are thought to have originated 260 million to 230 million years ago. Navajosphenodon sani is the oldest known direct ancestor of the tuatara. A nearly complete fossil, dated to 190 million years ago, was found in the Kayenta Formation in Coconino County, Arizona by Paleontologist Tiago Simões, who described his findings in a study published 2022 in Communications Biology. [Source: Elizabeth Rayne, SYFY, March 11, 2022]

Rhynchocephalian fossils such as Gephrysaurus, Palacrodon, and Polysphenodon are found as early as the middle Triassic Period (247 to 237 million years ago). By the early Jurassic Period (252 million years ago to 247 million years ago), rhynchocephalians such as Homeosaurus and Opistias had evolved in a form that resemble modern tuataras. Also in the Jurassic, rhynchocephalians acquired a diversity of habit and body form. There were were herbivorous aquatic forms such as Ankylosphenodon. [Source: Jennifer C. Ast, Animal Diversity Web (ADW)]

Between195 million and 70 million to years ago, rhynchocephalians were geographically widespread. Their fossils have been found in Europe, North America, and South Africa. According to the National Museum of Natural History (NMNH) in Washington D.C.: There is no data clarify the original range of tuataras on New Zealand . They were important animals, however, in the culture of indigenous New Zealanders, and their prevalence in art and legend of Maori people there suggests that tuataras had been much more abundant and widely distributed. [Source: Ronald I. Crombie,NMNH, and Robert P. Reynolds, USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, Washington Post November 11, 1998]

Tuataras — Living Fossils?

It is said tuataras are older than dinosaurs and they been called a living fossil like the coelacanth, a fish thought to have become extinct 60 million years ago that was found by a South African fisherman in the Indian Ocean in 1938. There are those that say the living fossil title is undeserved. Though very similar to its extinct ancestors, they have developed features that are different from their ancestors. They have also been likened to a living dinosaur as tuataras have a dinosaur-like diapsid skull and other anatomical features shared with prehistoric reptilians. [Source: Bruce Musico, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

a) a tuatara; b, what the tuatara’s genome says about its eveolutionary origin;

c) rhynchocephalians fossils globally, tuatara fossils in New Zealand (triangle = Triassic; square = Jurassic; circle = Cretaceous; and diamond = Palaeocene; In the map of the New Zealand distribution (c, bottom); asterisk = Miocene; cross = Pleistocene; circle = Holocene; blue triangle = extant population) ; Rhynchocephalians appear to have originated in the early Mesozoic period (about 250–240 million years ago (MA) and were commonand globally distributed for much of that era; The geographical range of the rhynchocephalians progressively contracted after the Early Jurassic epoch (about 200–175 Ma); the most recent fossil record outside of New Zealand is from Argentina in the Late Cretaceous epoch (about 70 Ma); c, The last bastions of the rhynchocephalians are 32 islands off the coast of New Zealand; from Nature

According to the National Museum of Natural History (NMNH) in Washington D.C.: Although externally very lizard-like, this two-foot reptile is the only surviving member of a distinct order of reptiles, Rhynchocephalia. The tuatara originally was described in the early 1830s as a member of the lizard order, but later the distinctiveness of the tuatara was recognized and a separate order was erected for it and its fossil relatives. [Source: Ronald I. Crombie,NMNH, and Robert P. Reynolds, USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, Washington Post November 11, 1998]

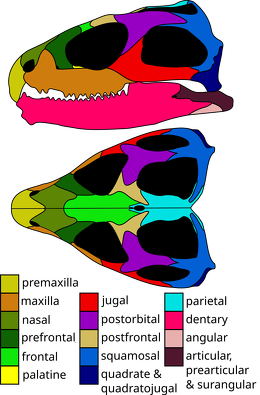

The tuatara's skeleton differs from that of all other living reptiles in that the tip of the upper jaw overhangs the lower, forming a small, beak-like point. This feature gave rise to the common term "beak-heads" for this order. Additional specimens resulted in the description of other species. By 1990, modern systematic techniques had characterized two extant species and one extinct species and had determined that the surviving populations were greatly reduced in numbers and distribution, some going extinct as recently as 1970.

Tuatara Subspecies, Habitats and Where They Are Found

The two recognized species of tuatara (tuataras and Brothers Island tuataras) live on 32 small, relatively inaccessible, islands off the northeastern and northern coast of the North Island of New Zealand and in the Cook Strait between the North and South Islands of New Zealand. The species was once widely distributed throughout New Zealand, but became extinct in some places on the mainland before the arrival of European settlers perhaps as a result of predation by rats. on the first humans on New Zealand . [Source: Bruce Musico, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

There is currently considered to be only one living species of tuatara. Two species were previously identified: 1) the northern, common or spotted tuatara (previously known as Sphenodon punctatus), and 2) the much rarer Brothers Island tuatara (previously known as Sphenodon guntheri) , which is confined to North Brother Island and some neighboring islands in the Cook Strait between the North and South Islands of New Zealand. A 2009 paper re-examined the genetic bases used to distinguish the two supposed species of tuatara, and concluded they represent geographic variants of one species. Despite this study, many researchers and government agencies continue to recognize Brothers Island tuataras as a distinct species. Brothers Island tuataras are smaller and have longer reproductive cycles than common tuataras.

tuatara range: Circles represent the common; North Island tuatara, and squares the Brothers Island tuatara; Symbols may represent up to seven islands

According to the National Museum of Natural History (NMNH) in Washington D.C.: There is no data clarify the original range of tuataras on New Zealand. They were important animals, however, in the culture of indigenous New Zealanders, and their prevalence in art and legend of Maori people there suggests that tuataras had been much more abundant and widely distributed. The decline of tuataras is directly related to habitat destruction by Europeans and predation by animals they introduced — rats, cats and pigs. However, extinction of at least one species predated European arrival, suggesting that other factors may have been involved. It is remarkable that any tuataras survived, considering that all other members of the order had been extinct for tens of millions of years. The few remaining tuataras cling to existence on tiny bleak islands where they share burrows with sea birds, finding sustenance and shelter from the outside. [Source: Ronald I. Crombie,NMNH, and Robert P. Reynolds, USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, Washington Post November 11, 1998]

The chilly, windy islands where tuataras live, are a difficult for most animals to live, particularly reptiles. The islands have cliffs on many shorlines and are frequently buffeted by strong wind., The vegetation is often stunted and comprised largely of salt- and wind-tolerant species. Most islands are also home to several species of sea birds, whose nutrient-rich guano helps support the island's ecosystem.

The climate is cold and damp. Temperatures rarely exceed 21̊C (70̊F). The humidity is usually around 80 percent. The temperature may often dip to near freezing. Tuataras are able to maintain normal activities in temperatures as low as 7̊C (45̊F) . The preferred body temperature is between 15.5 and 21 degrees C (60 and 70 degrees F) — the lowest optimal body temperature of all reptiles. At temperatures above 24̊C (76̊F) degrees. Tuataras show signs of distress at high temperatures, and most will die if the temperature exceeds 28̊C (82̊F) for a prolonged period.

120-Year-Old Tuatara

Tuatara probably have the slowest growth rates of any reptile — continually growing larger at a slow pace for the first 35 years of their lives. The average lifespan is about 60 years, but they can live well over a 100 years, making them one of the longest living animals and the second longest lifespan reptile after tortoisess. Some experts believe that captive tuatara could live as long as 200 years. One of the oldest tuataras, Henry, was at least 123 years old in 2022. He lives at the Southland Museum and Art Gallery, where there's a "Tuatarium" habitat. Henry and his mate Mildred were still laying eggs together as of 2009, when he was already 111 (though Mildred was thought to be in her 70s). [Source: Zoë Miller,Azmi Haroun, Business Insider, December 25, 2022]

Why do tuataras live so long? Tuataras are primarily nocturnal and are unusual for reptiles in their tolerance for cool temperatures. The high humidity and low temperatures of their environment helps tuataras to maintain a healthy shed cycles, slows the aging process and affects their heart and metabolic rates. Tuataras are sluggish nature and have a low body temperature, with an optimal range much lower than other reptiles. They have one of the slowest growth rates of any reptile, taking up to 35 years to reach full size and sexual maturity, which takes around 15-20 years. This slow development is part of their overall slow-aging life history. In addition, Wild tuatara populations are found on islands free of introduced mammalian predators that would prey on their eggs and young, contributing to their high survival rates. [Source: Google AI Amanda Johns, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Tuataras have a a large number of genes that protect against cellular damage and aging. Research has identified a greater number of genes in tuataras that protect them against age-related damage and cellular deterioration compared to other vertebrates. These include selenoproteins, which are vital in this protective process. The tuatara genome is one of the largest of any vertebrate, with a complex and unique structure that contains a high number of repetitive DNA segments and genes that may contribute to their unique biological traits, including their longevity and disease resistance.

Tuatara Characteristics

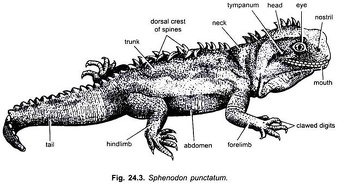

Tuataras differ from lizards in that their teeth are attached to bone and they have two temporal openings in their skull and no external ear. Males lack conventional sexual organs. Tuatara means “bearing spines”, referring to the single row of spines running along their dorsal side. [Source: Amanda Johns, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|] Adult tuataras are range in weight from 0.4 to one kilogram (0.88 to 2.20 pounds) and have a very slow metabolism .They are cold blooded (ectothermic, use heat from the environment and adapt their behavior to regulate body temperature). Their average basal metabolic rate is 0.0605 watts. Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present: Males are larger than females. Females tend to be around 45 centimeters (1.5 feet) in length while males are around 60 centimeters (two feet) long. Male tuataras have a noticeable crest down the back of the neck, and another down the middle of the back. Females have a less developed version of this. The male abdomen is narrower than the female's. [Source: Bruce Musico, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Tuataras are stout reptiles and iguana-like in appearance, with dorsal spines on the neck and head and a thick tail. They may be grey, olive, or brickish red in color, typically matching their environment, and can change over the reptile's lifetime. Adults shed their skin at least once per year as adults, and juveniles do so three or four times a year. The spiny crest on a tuatara's back is made of triangular, soft folds of skin and can be stiffened for display.

Tuataras have a diapsid skull with two openings on either side. Unlike all other living toothed reptiles, the tuatara's teeth are fused to the jaw bone (acrodont tooth structure). and is a very long-lived species. The coronoid process of the dentary is prominent, bones in the upper jaw have been modified into teeth-like chisels that overhang the lower jaw, and some of the palatine teeth are enlarged. According to Animal Diversity Web: Their "primitive" morphology and physiology led herpetologists in the early twentieth century to consider the tuatara a living fossil and maladapted relic, but more recent work has suggested on the contrary that tuataras are well-adapted to its current habitat. [Source: Jennifer C. Ast, Animal Diversity Web (ADW)]

The Brothers Island tuatara has olive brown skin with yellowish patches, while the colour of the northern tuatara ranges from olive green through grey to dark pink or brick red, often mottled, and always with white spots. In addition, the Brothers Island tuatara is considerably smaller. Brothers Island tuatara have similar jaw morphology as northern tuatara.

Tuatara Senses and Communication

Tuataras sense using vision, touch, sound and chemicals usually detected with smell and communicate with vision and sound. The pupils of the tuatara readily expand and contract, which helps them see during the daytime and at night. Although they have no external ears, they are still able to hear. They are also able to use touch, smell, and taste to perceive their environment. During breeding season males may croak, which is used as a mating call to alert females to their presence. [Source:Amanda Johns, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Tuatara eyes can focus independently, and have three types of photoreceptive cells, all with fine structural characteristics of retinal cone cells used for both day and night vision, and a tapetum lucidum which reflects onto the retina to enhance vision in the dark. There is also a third eyelid on each eye, the nictitating membrane. Five visual opsin genes are present, suggesting good color vision, possibly even at low light levels. Tuataras posess a "parietal eye" on the top of their head. This pineal spot appears somewhat functional at birth, but becomes covered with skin after several months and does not appear to serve a functional purpose thereafter. Other lizards also have this "third-eye," which contains a retina and is functionally similar to a normal eye, though the function has not been clearly recognized. [Source: Wikipedia]

Tuataras lack external ears. Along with turtles, they have the most primitive hearing organs among the amniotes (most mammals, reptiles and birds). There is no eardrum and no earhole. middle ear cavity is filled with loose mostly fatty tissue. The stapes (small stirrup-shaped bones in the middle ear that transmit vibrations) comes into contact with an immovable quadrate (middle ear bone). The hair cells are unspecialised and respond only to low frequencies. Though the hearing organs are poorly developed and primitive, tuataras can still show a frequency response from 100 to 800 Hz, with peak sensitivity of 40 dB at 200 Hz. Vocalizations within their hearing range suggest that tuataras do aurally communicate with each other, perhaps especially in areas where burrow density reaches a spacing of only two meters.

Tuataras appear to have a fairly good sense of smell. Animals that depend on the sense of smell to capture prey and interact with their environment have many odorant receptors. These receptors are expressed in the dendritic membranes of the neurons for the detection of odors. The tuatara has around 472 such receptors, a number more similar to what birds have than to the large number of receptors that turtles and crocodiles may have.

Tuatara Behavior and Diet

Tuataras are terricolous (live on the ground), nocturnal (active at night), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), territorial (defend an area within the home range). and solitary. Tuataras are active at quite low temperatures, and they sometimes bask in the sun although less than many other reptiles. When they bask tuataras tend do so at the entrance to their burrows when it is sunny.[Source: Bruce Musico, Amanda Johns, Jennifer C. Ast, Animal Diversity Web (ADW)]

Tuataras are carnivores (eat meat or animal parts) and also recognized as insectivores (eat insects). They will eat whatever they can catch and are primarily nocturnal predators of arthropods, especially those associated with sea bird colonies such as beetles, snails and worms. They are found and giant cricket-like wetas (New Zealand orthopterans). Given the opportunity, they do eat small lizards, frogs, bird eggs and juvenile seabirds. Seabird guano helps to maintain invertebrate populations on which tuatara predominantly prey. Wetas can reach the size of a mouse. Young tuataras are also occasionally cannibalized. The diet of tuatara varies seasonally. They consume mainly fairy prions and their eggs in the summer. Due to their low metabolic rate, the tuataras eat much less frequently than other reptiles. |=|

Weather influences tuatara activity levels, with their activity level declining in chillier weather. There is some debate as to whether tuataras hibernate. They seem to at least engage is some kind of torpor (a period of reduced activity, sometimes accompanied by a reduction in the metabolic rate, especially among animals with high metabolic rates). Older tuataras are active from dusk until dawn. Young tuataras are often diurnal (active mainly during the daytime). Their faster speed allows them to escape possible predation. Older tuataras set up territories that they defend with displays or physical attacks.

Little is known about the social structure of tuataras. Despite being territorial tuataras typically live in close proximity to each other. The home territories of Brother Island tuataras range from 11.5 to 86.7 square meters. Males become aggressive when other male tuataras enter their territory. Females also become aggressive towards other females, but often permit males into their territory. Female territories are typically half the size of males' and in some cases overlapping territories can occur between sexes.

Tuataras live singly in burrows, usually made by seabirds such as petrels, prions, and shearwaters. During the day, most Brother Island tuataras inhabit burrows along cliff faces in open areas featuring low coastal vegetation, and usually offer both shade and sunlight to aid in heat regulation. Their burrows can measure about five meters in length and 30 centimeters in depth. Some of the small islands of New Zealand are particularly rich in petrels and shearwaters. David Attenborough wrote: “In New Zealand, shearwaters returning after months at sea to nest in tunnels on the tops of cliffs often find that in their absence their holes have been taken over by primitive lizards, tuataras. Once established, a tuatara becomes the permananet year-round caretaker, keeping the hole clear of blockages so that when the birds return the next season, all they have to do is clear out the nest chamber at the far end. A tuatera will eat shearwater eggs and chicks but considerately it never takes those belonging to its landlord that lie at the far end of the shared tunnel.”

Male tuataras show aggression towards other males by inflating their bodies, elevating their crests, and darkening the skin between the shoulders and neck crest. Males also approach females with this display prior to breeding. Territorial displays are similar and may also include approaches, head bobbing from side to side, and mouth gaping. Tuatara of both sexes defend territories, and do threaten and eventually bite intruders. The bite can cause serious injury. Tuatara will bite when approached, and do not let go easily.

Tuatara Reproduction and Offspring

Tuataras are oviparous, meaning that young are hatched from eggs. They have very slow reproduction rates — maybe the longest of any reptile. They take between 10 and to 20 years to reach sexual maturity, and reproduce only once every three to four years, and then toung are not born until two years after the egg-producing process starts. Tuataras usually mate from mid-summer to early autumn (January-March) and the eggs are laid the following spring or early summer (October-December). [Source: Wikipedia, Jennifer C. Ast Bruce Musico, Amanda Johns, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Little is known about the mating systems in tuataras, but males tend to be highly territorial and mate with multiple females if given the chance. Male tuataras generally outnumber females in their native environments.Male tuataras do not have any external sex organs. Copulation is achieved by a meeting of the cloacal regions in what is known as a "cloacal kiss." During courtship, a male makes his skin darker, raises his crests, and parades toward the female. He slowly walks in circles around the female with stiffened legs. The female either allows the male to mount her, or retreats to her burrow. Instead of a penis males have rudimentary hemipenes (paired male reproductive organs that turn outward during mating) that deliver sperm to the female during copulation in which the male lifts the tail of the female and placing his vent over hers — the "cloacal kiss". The sperm is then transferred into the female, much like the mating process in birds. Along with birds, tuatara lost their ancestral penis. They have fast swimming sperm though — two to four times faster than other reptiles studied.

Clutches of five to 18 eggs are deposited in nests that female tuataras dig. Incubation takes from 12 to 15 months, with the development of the embryo stopping during the winter months. Tuatara eggs have a 0.2-millimeter thick shell that consists of calcite crystals embedded in a matrix of fibrous layers. The mean clutch size of Brothers Island tuataras is approximately 6.5 eggs. Each egg has a mean weight of 4.9 grams, and the shell has a white coloration with a rather soft texture. It takes the females between one and three years to provide eggs with yolk, and up to seven months to form the shell. It then takes between 12 and 15 months from copulation to hatching. Survival of embryos appears to be higher in moist conditions. The sex of a hatchling depends on the temperature of the egg, with warmer eggs tending to produce male tuatara, and cooler eggs producing females. Eggs incubated at 21°C (70°F) have an equal chance of being male or female. However, at 22°C (72°F), 80% are likely to be males, and at 20°C (68°F), 80% are likely to be females; at 18 °C (64 °F) all hatchlings will be females.

There is no parental involvement in the raising of offspring. Young tuataras escape their eggs by using an egg tooth. This structure is located on the tip of their head between the nostrils and is lost after the first couple of weeks. Newly hatched tuataras resemble miniature versions of adults, [Source: Amanda Johns, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Tuatara Become a Father at Age 111

Wild tuatara are known to be still reproducing at about 60 years of age; "Henry", a male tuatara at Southland Museum in Invercargill, New Zealand, became a father (possibly for the first time) on in January 2009, at age 111, with an 80 year-old female. Associated Press reported: Henry the tuatara and his younger mate Mildred produced a dozen eggs last month after mating at the Southland Museum on New Zealand's South Island in March. Tuatara curator Lindsay Hazley said Henry has lived at the museum's special enclosure for Tuatara since 1970 and had shown no interest in sex until he recently had a cancerous growth removed from his genitals. He was now enjoying the company of three females and might breed again next March. [Source: Associated Press, August 8, 2008]]

Mildred laid 12 eggs in June, with 11 surviving. Museum tuatara curator Lindsay Hazley told NZPA 10 babies had hatched and the 11th was half way out of its egg this morning. It was great to see the babies, which ranged in size from wee to medium, hatch, he said. "It's the completion of a love story."

They had had quite a slow hatching process and it was early days, but they all appeared to be doing well. The babies did not need to eat immediately after being hatched and would be offered bugs in about 10 days' time, he said. Tuatara parents did not play an active role in raising babies and were actually likely to eat anything that was small and moved, Mr Hazley said.

Henry had formerly been known for his aggression, was not interested in sex and had to be kept isolated from other tuatara. However, he got his mojo back after a cancer growth was removed from his bottom. He was now living with three female tuatara "in great harmony" and was expected to mate with Lucy this year, Mr Hazley said. "He's had a major personality transplant."

Mr Hazley hoped to enter Henry into the breeding programme regularly. "It adds a whole new genetic diversity into our breeding stock, which is going to be very useful." He expressed relief about Henry "finally getting it together" after looking looking after him for so long. "I thought I'd written him off there for about 20 years." The museum is the home to more than 70 tuatara,

Tuatara Humans and Conservation

On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List tuatara are listed as a species of Least Concern. Natural populations have been augmented by the establishment of about 10 new island or mainland sanctuary populations using translocations. The current global population is estimated to be around 100,000 individuals. The Brother island subspecies is classified as vulnerable. There are 400 to 500 of them. [Source: Bruce Musico, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

In 1895, New Zealand awarded the tuatara strict legal protection. On the U.S. Federal List tuatara are classified as Endangered. In CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild) they are in Appendix I, which lists species that are the most endangered among CITES-listed animals and plants. This is the most restricted classification for a species. In order for a zoo to possess this species, very demanding rules must be followed, and the public display of tuataras has only recently been allowed. Access to the islands that the tuatara inhabit is strictly regulated, and for many years no tuataras have been removed from any island for any reason. |=|

Tuataras were once widespread in New Zealand, but are now highly Endangered, primarily because of human influence. Humans arriving in New Zealand used tuataras as a food source, and perhaps more devastatingly, introduced the rat, which decimated the population by eating eggs and juveniles. Tuataras are currently listed under CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild) places them in Appendix I, and by RedList as Vulnerable. |=|

Sea bird species that inhabit North Brother Island sometimes attack tuataras, often for territorial reasons. Swamp harriers (Circus approximans) and New Zealand falcons (Falco novaezeelandiae) are known to catch and consume younger tuataras. Invasive species like rats can take tuataras. Young tuataras are diurnal, which makes them more vulnerable to birds of prey, but they are also faster than older tuataras, which helps them avoid being prey to raptors as well as older tuataras. Tuataras can drop and regenerate their tails to escape predation. A great effort has been made yo make sure there are no invasive species such as cats, rats, stoats and weasels on islands inhabited by tuataras. [Source: Amanda Johns, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org , National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New Zealand Geographic, New Zealand Tourism, New Zealand Herald, Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various books, websites and other publications

Last updated September 2025