Home | Category: Nature, Environment, Animals

SEALS, SEA LIONS AND FUR SEALS IN NEW ZEALAND

There are three resident pinniped species in New Zealand: 1) endemic New Zealand fur seals (kekeno); 2) New Zealand sea lions (pakake/whakahao), and 3) Southern elephant seal which breeds on subantarctic islands. Leopard seals are often seen in New Zealand waters. They primarily inhabit the Antarctic region but show up in New Zealand's waters during autumn and winter.

New Zealand fur seals are the most common seal in New Zealand, with a growing population, found around the mainland and subantarctic islands. New Zealand sea lions are also known as Hooker's sea lions. They are a rare and endemic species that breeds on the subantarctic islands and is slowly recolonizing the coast of the South and Stewart Islands. New Zealand fur seals can be identified by their smaller size and pointed nose. New Zealand sea lions are larger and are considered one of the world's rarest sea lion species. Southern elephant seals breed on New Zealand's subantarctic islands, with occasional visits to the local coastlines.

Most of the species found in New Zealand are sea lions and fur seals not real seals. Seals have furry, generally stubby front feet — thinly webbed flippers, actually, with a claw on each small toe — that seem petite in comparison to the mostly skin-covered, elongated fore flippers that sea lions possess. Sea lions have small flaps for outer ears. The "earless" or "true" seals lack external ears altogether. You have to get very close to see the tiny holes on the sides of a seal’s sleek head. Sea lions are noisy. Seals are quieter, vocalizing via soft grunts. [Source: NOAA]

While both species spend time both in and out of the water, seals are better adapted to live in the water than on land. Though their bodies can appear chubby, seals are generally smaller and more aquadynamic than sea lions. At the same time, their hind flippers angle backward and don't rotate. This makes them fast in the water but basic belly crawlers on terra firma. Sea lions, on the other hand, are able to "walk" on land by rotating their hind flippers forward and underneath their big bodies. Sea lions congregate in gregarious groups called herds or rafts that can reach upwards of 1,500 individuals. It's common for scores of them to haul out together and loll about in the sand, comprising an amorphous pile in the noonday sun.

All marine mammals of New Zealand are protected by the Marine Mammals Protection Act of 1978. A variety of laws, regulations, protected areas and sanctuaries in New Zealand and Australia help protect them. .In the early 19th century, thousands, perhaps millions of seals were slaughtered. In 1806, a single vessel arriving in Sydney harbor from New Zealand contained 60,000 seal skins. Today, many seals continue to be lost when they drown in fishing nets. A total of 75 females were accidentally drowned in a single year.

Related Articles:

SEALS AND SEA LIONS IN AUSTRALIA: SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

SEALS: CHARACTERISTICS, SENSES, WHISKERS, SPECIES ioa.factsanddetails.com;

SEALS: HISTORY, BEHAVIOR, DIVING, FEEDING, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

SEA LIONS AND FUR SEALS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SPECIES, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

SEALS AS PREY FOR ORCAS, GREAT WHITES AND POLAR BEARS ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

SEALS AND HUMANS: CLOTHES, HUNTS AND THE MILITARY ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

FUR SEALS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SPECIES ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

ELEPHANT SEALS, THEIR BEHAVIOR AND AMAZING DIVING ABILITY ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

SOUTHERN ELEPHANT SEALS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, MATING ioa.factsanddetails.com

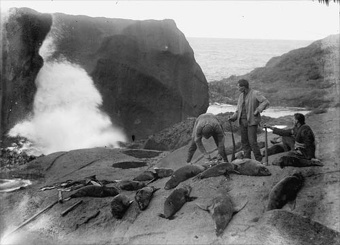

Sealers in New Zealand

Seals and sea lions were hunted another for their meat, oil and fur. Leather is sometimes made from seals. Commercial sealers traditionally drove the seals to a designated area and killed them with blow to soft parts of their skulls. Sealing — the hunting of seals — was widely practiced in the Pacific Ocean in the 19th century.

By that time Sealing was established around the coast of Australia and sealers travelled all around the Pacific. Fur seal skins were sold on the London market but more importantly was a tradeable commodity in China. When China had a monopoly on the international tea trade, sea skins were traded for tea. The Chinese found little of value in the normal trade goods offered by European traders. They demanded payment in gold. Seal skins were a good alternative. [Source: New Zealand History 1800 -1900, A blog to assist the students in Level 3 NCEA History at Wellington High School, February 28, 2008 ]

In New Zealand, the first Sealers set up camp in Dusky Sound (Fiordland) in 1792. Mainly ex-convicts, they were outfitted and supplied by entrepeneurs based in Port Jackson (Sydney). The job was simple. Kill as many Fur Seals as possible, skin them, cure the hide with salt and wait to be picked up. A good crew could return to Sydney with several thousand skins.

See Separate Article: FIRST EUROPEAN IN NEW ZEALAND: EXPLORERS, SETTLERS, SEALERS AND THEIR IMPACT ON THE MAORI ioa.factsanddetails.com

New Zealand Fur Seals

New Zealand fur seals (Arctocephalus forsteri) are also known as Australasian fur seals, South Australian fur seals, Antipodean fur seals and long-nosed fur seals. They are "eared seals," meaning they have visible external ear flaps and can use all four flippers to move on land. Sea lions are also eared seals. The name New Zealand fur seal is used by English speakers in New Zealand; kekeno is used in the Māori language. In 2014, the name long-nosed fur seal has was proposed for the population living in Australia.

New Zealand fur seals are a generally non-migratory coastal species. Before being driven to near extinction during the sealing era, they were were found all around the North and South Islands including many offshore islands and sub-Antarctic islands. Today, they are found in New Zealand mainly on and around the South Island at Big Green Island, Open Bay Islands, West Coast, Cape Foulwind, Cascade Point, Wekakura Point, Three Kings Islands, eastern Bass Strait, the Nelson-northern Marlborough region, Fjordland, New Zealand's sub-Antarctic islands Snares, Campbell, Chatham Islands, Antipodes, Bounty Islands, Stewart Island, and the islands of the Foveaux Strait. [Source: Dorothy Landgren, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

A a small colony lives at Cape Palliser near Wellington on the North Island and near the continental shelf edge of Otago Peninsula. There is also a population in southern and western Australia, Kangaroo Island, Tasmania and Victorian coastal waters. The New Zealand and Australian populations rarely overlap. The distribution of these fur seals is largely tied in with the distribution of their food sources. When New Zealand fur seals do migrate it’s not so far and in the breeding season. In the fall and winter seasons they tend to stay within 162 to 178 kilometers (100 to 110 miles) of their rookery. During the summer, they stay closer, 70 to 80 kilometers (45 to 50 miles)

New Zealand fur seals are typically found in the water at depths between zero to 380 meters (1247 feet) and on land on rocky coastlines and offshore islands that provide protection from strong ocean waves. They seem to prefer beaches with large rocks, reefs just off the coast and smooth rocky ledges to gain easy access to the sea. Warmer islands tend to have rock pools that the seals use for cooling. Vegetation such as tussock and scrub are often in breeding areas and nurseries. Non-breeding colonies are more flexible in where they live.

New Zealand fur seals are not endangered or threatened although they once were.. They are designated as a species of least concern on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List and have been placed by the Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) in Appendix II, which lists species not necessarily threatened with extinction now but that may become so unless trade is closely controlled. New Zealand fur seals were a popular source of food and clothing to the Maori. When European sealers arrived in the 19th century, they nearly wiped the seals out in their pursuit of meat, oil and money. caused the extinction of fur seals.

In 1972, fur seals were given national protection. But even after that their troubles continued Trawling nets entangled and drowned more than 10,000 New Zealand fur seals from 1989 to 1998. This led to the creation of more sea-mammal friendly trawl nets. In recent years, environmentalists have been advising fish farms to build seal-proof barriers or away from fur seal habitats. Today, New Zealand fur seals in New Zealand and Australia are protected by a variety of laws, regulations, protected areas and sanctuaries. They are a tourist attraction and help make a living through that but tourism can disturb the seals. They often abandon tourist spots for quieter island shores.

New Zealand Fur Seal Characteristics

New Zealand fur seals range in weight from 30 to 250 kilograms (66 to 550 pounds) and range in length from one to 2.5 meters (3.3 to 8.20 feet). They have a pointed nose, long whiskers and ear flaps. The adult coat consists of two layers: 1) a thick undercoat; and 2) an upper coat that is a dark grey-brown on the back side, which gradually lightens to a lighter gray-brown on the undersides, providing in seawater and on rocky shores. The dark appearances of New Zealand fur seals comes from their deep chestnut undercoat and the dark gray coarse guard hairs of their topcoat. When the fur is wet, it appears darker, but when it is dry the white tipped guard hairs give off a silvery sheen.[Source: Dorothy Landgren, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is very much present with New Zealand fur seals: Males are three times heavier and and 1.3 times longer than females. Adult males range in length from 1.5 to 2.5 meters (4.9 to 8.20 feet) long and weigh 120 to 180 kilograms (264 to 550 pounds). Adult females average one to 1.5 meters (3.3 to 4.9 feet) long and weigh 30 to 50 kilograms (66 to 110 pounds). The largest male on record weighed 250 kilograms (550 pounds) and the largest female weighed 90 kilograms (198 pounds). Males and females also have different shapes. Bulls are massive throughout their neck and shoulders, while females possess an overall slender physique. Even male pups are significantly larger than female pups, which is due the high lipid reserves of female pups, while the male pups consist of more lean muscle tissue. The bulls have long, thick guard hairs that make up their coarse mane. The females do not develop this mane. ,

New Zealand fur seals are endothermic (use their metabolism to generate heat and regulate body temperature independent of the temperatures around them). Physically there are no differences between the New Zealand fur seals in New Zealand and those in Australia. Only genetic differences distinguish them. The longest-living observed New Zealand fur seals were a 25 year-old female and a 19-year-old male. The average lifespan in the wild is estimated to be 15 years for a male and 12 years for a female. Known predators include sharks, orcas (killer whales), leopard seals, New Zealand sea lions, and humans. The main anti-predator defense of New Zealand fur seal is the camouflage coloring and ability to swim swiftly and maneuver through the water and clamber ashore. Many pups don't make it through their first year. e. During the first 300 days, pup mortality is approximately 40 percent. A captive age of 23.1 years has been recorded.

New Zealand Fur Seal Food and Eating Behavior

New Zealand fur seals are carnivores (eat meat or animal parts) and recognized as piscivores (eat fish) and molluscivores (eat mollusks) as well as birds, crustaceans and other marine invertebrates. The New Zealand fur seals are opportunistic foragers which vary their diet according to what is available in a certain season and at a certain place. They use their whiskers to feel underwater vibrations, which help them locate food. [Source: Dorothy Landgren, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Among the animals New Zealand fur seals have been observed eating or found in their stomachs or scat are small penguins like the rockhopper penguins, short-tailed shearwaters, arrow squid, broad squid, warty squid, Antarctic flying squid, butterfish, New Zealand octopus, krill, lamprey, blind eel, ling, ahuru, crayfish, crab, lanternfish, juvenile red cod, blue cod, flounder, whiptail, kahawai, horse mackerel, redbait, anchovy, ocean jackets, hagfish, spiny dogfish, school shark, sprat, silverside, lightfish, hoki, rattail, tarakihi, opalfish, Graham's gudgeon, barracouta, rostfish, warehou, lemon sole, sole, wary fish, dory, yelloweyed mullet, dwarf cod, Oliver's rattail, yellow weever, silver warehou, Southern blue whiting, javelin fish, deepsea smelt, common roughy, seaperch, and pilchard. Few of these species are commercially fished.

Females are mid-water feeders with the distance and depth depending on the season and the age of their pups. During the breeding season, they feed just beyond the continental shelf. During the fall and winter seasons, they venture out for longer periods of time and dive further depths. Adult males feed over the continental slope and the juvenile seals forage in areas containing migrating lanternfish. Both the adult males and females sometimes forage in shallow waters (0 to 20 meters), but most often do benthic dives to near the sea bottom off continental slopes. Females dive 60 to 80 meters and males dive 100 to 200 meters. The longest dive and deepest dive for males lasted 14.8 minutes and was 380 meters deep; for females it was 9.3 minutes and 312 meters.

New Zealand Fur Seal Behavior and Communication

New Zealand fur seals are terricolous (live on the ground), natatorial (equipped for swimming), diurnal (active mainly during the daytime), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), nomadic (move from place to place, generally within a well-defined range), territorial (defend an area within the home range), social (associates with others of its species; forms social groups), and have dominance hierarchies (ranking systems or pecking orders among members of a long-term social group, where dominance status affects access to resources or mates). [Source: Dorothy Landgren, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

New Zealand fur seals are good swimmers but awkward on land. The home territories of New Zealand fur seals on shore range from zero to 100 square meters. Males form territories during the breeding season. Juvenile seals and non-breeding adults generally stay away from the breeding grounds and choose the less ideal rocky hauling spots during the breeding season. When large adult males on land become frightened they amble as fast as they can to the sea and the entire herd follows. They swim out a few meters before they look back to examine the source of alarm.

Outside of the breeding season male New Zealand fur seals practice comfort behaviors such as scratching, rubbing and grooming for long periods of time. They are able to perform these comfort behaviors with their teeth, wrists of the fore flippers and their nails on their hind flippers. They even rub up against jagged rocks to get the places on their body they otherwise couldn’t reach. Grooming behaviors are most often seen after the seal hauls themselves on to the shore from the water. When the days are cold, fur seals are found sleeping on land with their flippers tucked under them and their bodies slightly curled up to retain heat. The body of New Zealand fur seals contains a large amount of fat for insulation so cold weather is rarely an issue. On warmer days fur seals lay with their body and fins extended for maximum heat loss. In mid-summer fur seal activity slows down and they seek out shade, pools of water, or take dips into the sea to cool off.

New Zealand fur seals and sense using vision, touch, sound, vibrations and chemicals usually detected with smelling or smelling-like senses and communicate with vision, touch, sound, chemicals detected by smelling and pheromones (chemicals released into air or water that are detected by and responded to by other animals of the same species). The seal’s whiskers are useful in sensing, underwater vibrations to locate food. Territory boundaries, status within a group and readiness to fight can be recognized by posture and physical movement. The alert posture shows general awareness, where an open-mouth display is used as an aggressive and a submissive display. Males display their status with a full neck display in which a male sits in an upright, vertical position with his chest protruding out, head tilted back and nose pointed up towards the sky. When smaller-necked males see this they back off to avoid confrontation. If the two males are the same size, the full neck display is done for a long period of time and male’s chests stick out so far they often contact the chest of their rival. In keep the display going, while maneuvering for an attack position neck waving is conducted. When males carry their neck and head in a low dipped position, it indicates submission. The male seal that loses a full neck display confrontation faces away to appease the winner. Young pups have been seen doing these displays during play-fighting with one another. [Source: Dorothy Landgren, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

New Zealand fur seals vocalizations include low intensity threatening calls. Territorial males often bark to demonstrate their status or give a loud, deep, throaty, gruff call known as a choke call. The bark can also show sexual interest. Both males and females whine or squeal to express submissive. Male fur seals also whine or squeal to appease the winning male after a fight or confrontation. Females threaten others by producing a high-pitched raspy growls. When a female needs to locate her pup she uses both vocalization and vision. Once the female leaves the water she holds her body upright, extends and arches her head and neck forward searching, producing a high-pitched, rising screech. The returned call from the pup is also a high-pitched screech, but more monotone. To confirm recognition the female uses her senses of smell to either accept or reject the pup as they sniff each other’s faces and noses.

New Zealand Fur Seal Mating, Reproduction and Offspring

New Zealand fur seals are polygynous (males have more than one female as a mate at one time) and employ delayed implantation (a condition in which a fertilized egg reaches the uterus but delays its implantation in the uterine lining, sometimes for several months). They engage in seasonal breeding — once yearly between late October and early February. To increase breeding opportunities, males remain ashore for as long as possible, surviving off energy reserves. They typically do not eat for the two to three months of breeding season.Around eight days after giving birth, females go into estrus. When the female is in estrus she show interest in the male who occupies the territory she gave birth in by rubbing up against him and displaying very little aggression. Copulation consists of mutual touching, and the male mounting and biting. When the female begins to the resist the male, he soon ejaculates and dismounts the female. Copulation generally takes from five to 30 minutes. The average gestation period is nine months.The number of offspring is one. The average weaning age and time independence is nine to 10 months. Females reach sexual maturity at four to eight years, usually around age five years. Males reach sexual maturity at four to five years. Females can deliver their first pup at this time, but males don’t become strong and big enough to competer for and defend a territory for mating until eight to 10 years. [Source: Dorothy Landgren, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

New Zealand fur seal males defend their territory with a harem of five to eight females. They typically choose an island as a breeding site. When they arrive at their island, males compete with others to establish their territories two weeks before pregnant females come ashore. Successful males with established territories are typically seven to 15 years of age. Both male and female seals that aren’t breeding find other hauling grounds to rest upon during that season. The ideal territory has many shaded areas for the male and his group of females to cool themselves. Sheltered and shaded areas near the sea are frequently fought over throughout the breeding season and seldom left unoccupied. Seals stay at the hauling and breeding from around late October to early February. As the breeding season progresses and the number of territorial males rises and the size of their territory decreases. Much of communication during the breeding season is aggressive as males confront each other keep the females in their territory and away from the other males. The longer a female is on a male’s territory, the higher the chances are that she will mate with him. Each male performs his herding techniques slightly different from the others. Females are allowed to move about the hauling grounds, but the herding territorial males make it difficult by blocking access for up to an hour at a time. Smelling is another key part of their mating behaviors. Males smell the face and perineal regions of females to determine if the female is ready to mate. If the female is not ready to receive the male she displays aggressive behaviors such as growling, snapping and moving away. Females become more aggressive right before and after birth. The male detects the female’s sexual readiness primarily by smell.

Seven to eight days after giving birth, females mate with the bull closest to them. Usually this is the male in territory they reside. Females breed anytime throughout the breeding season. However, only females breeding for the first time or females that didn't birth and rear a pup the year before are early season breeders. After fertilization the embryo goes through a two to four month delayed implantation. This allows females to birth and mate in the same breeding season. It also gives her body some recovery time between birthing and the development of her next pup. The pups are born between late November and mid-January, with an average length of 40 to 55 centimeters (1.3 to 1.8 feet). These pups are precocial, and can start suckling within 60 minutes. There is significant weight variation in the pups at birth, which may be explained by the considerable sexual dimorphism between males and females. Male pups weigh on average 3.9 to 5.6 kilograms at birth and females at birth weigh 3.3 to 4.8 kilograms. At 290 days old the male pups weigh 14.1 kilograms and females weigh 12.6 kilograms. From birth to 240 days of age the pups gained on average 24 grams and 0.86 centimeters a day, but this rate slowed after 240 days.

New Zealand fur seal females protect and nurse their pups. Six to twelve days after giving birth, cows leave their pup with other pups and begin going to sea and feeding for three-to-eight day intervals and then returning to their pup a two-to-seven-day nursing period. As pups gets older, the foraging trips by females gradually become longer and her time ashore becomes shorter. Females often remain with their harems group. When several females simultaneously leave their pups for longer periods to feed, the pups gather into small groups until each hears the call of its mother and returns to her to suckle. The older the pups get, the more adventurous they become. They swim in water pools, play with the other pups, and mimic battles. The birth mass of the pup is related to the changes in yearly conditions such as place of birth, the mother’s age, her experience, prey abundance, and the mother’s foraging efficiency. At five months, the pups shed their black coats for their more adult silvery-grey coats. Pups are capable of swimming at birth, but they spend their time practicing and building confidence when their mother is away on feeding trips. During the weaning period they also practice fishing in calm intertidal pools. At nine months, when the pups have reached independence, they run to hide in the ocean instead of rock crevices. When there is a perceived threat on land and the herd heads to sea, curious pups are often the first venture toward shore.

New Zealand Sea Lions

New Zealand sea lions (Phocarctos hookeri) are a species of sea lion that is endemic to New Zealand and primarily breeds on New Zealand's subantarctic Auckland and Campbell islands. Formerly called Hooker's sea lions, the are an endangered species but recently have been making a modest comeback, slowly breeding and recolonizing around the coast of New Zealand's South and Stewart islands. With their numbers estimated to be around 12,000, New Zealand sea lion are one of the world's rarest sea lion species. They are the only species of the genus Phocarctos. The Maori call them as pakake (for both males and females), whakahao (males) and kake (females). In the past they have been known by the scientific names Otaria flavescens and Otaria byronia.

New Zealand sea lions spend most of their lives near the windswept islands where they were born, and are sometimes feasted on by great white sharks. They can be seen occasionally on sandy beaches and cliffsides of the South Island and but more often in the subarctic islands off of southern New Zealand. They mainly inhabit the southern stretches of New Zealand’s territory in the Pacific with their colonies stretching the Foveaux Straight in the north to Macquarie Island in the far south. The main breeding areas are in the Auckland Islands, and to a lesser degree in the Campbell Islands. New Zealand sea lions were thought to have disappeared from mainland New Zealand more than a century ago due to human hunting. The first sighting of one was in 1993. [Source: David Ferland, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

New Zealand sea lions have adapted to a wide range of habitats. They live in polar, saltwater and marine environments and have been found in coastal areas at elevations up to 400 meters (1312 feet) high on hills, and in forests, and fields of the local islands they live on and dive to depths as deep as 600 meters (1968.50 feet). Most individuals though prefer to remain on sandy beaches and hunt primarily at depths of less than 200 meters. When breeding females seek shelter further inland they often hunt mainland birds and take eggs and nestlings.

New Zealand sea lions have been listed as Endangered on the On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List since 2015 due to population decline, a restricted breeding range, and ongoing threats from fisheries. New Zealand's own Department of Conservation (DOC) lists the species as Nationally Critical under its threat classification system, indicating a very high risk of extinction in the wild. The DOC worries about interactions between local fishing vessels and New Zealand seal lions, which rely on arrow squid for food, but are also targeted by fishermen. Similar to how dolphins were caught by tuna fishermen, New Zealand seal lions have been caught accidentally by squid fishermen. The New Zealand Government has put limits on the numbers of New Zealand seal lions that can be caught in fishing nets. Once this limit is reached, the fishery must close operations for the remainder of the season. Another concern for New Zealand seal lions has been bacterial epidemics which have killed hundreds of adults and pups.

The only known predators of New Zealand seal lions are sharks and dogs on the mainland. Humans hunted them but not today and there are New Zealand laws protecting them. species. New Zealand seal lions are dominant predators in their habitat. They hunt endangered species themselves, including Southern Royal Albatrosses, which concerns some scientists. New Zealand seal lions have a mutualist relationship with the red-billed gulls. These birds perch on the backs of the seal lions picking off blowflies and other insects from the sea lion’s back and head.

New Zealand Sea Lion Characteristics and Diet

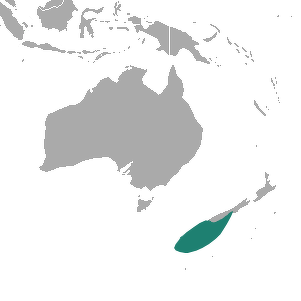

New Zealand sea lion range

New Zealand sea lions range in weight from 100 to 400 kilograms (220 to 880 pounds) and range in length from 1.6 to 3.5 meters (5.25 to 11.5 feet). They are endothermic (use their metabolism to generate heat and regulate body temperature independent of the temperatures around them) and have a very short, blunt head with a length to width ratio of 2:1, compared to an average ratio for fur seals and sea lions of 3:1. New Zealand sea lions are similar to Australian and South African sea lions in appearance. But unlike Australian sea lions, and also most other species of sea lion, New Zealand sea lions have a deep concave palate (2.2 centimeters in males and 1.45 centimeters in females), a dental formula of I: 3/2 C: 1/1 Cheek teeth: 6/5, and a smooth cylindrical projection of the tympanic bulla (an ear bone). The lifespan of New Zealand sea lions in the wild is 23 (high) years. [Source: David Ferland, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present: Males are larger than females. Sexes are colored or patterned differently. Males reach lengths of 3.5 imeters (11.5 feet) and weigh up to 450 kilograms. (990 pounds) Females reach lengths of around two meters (6.6 feet) and weigh up to 160 kilograms (332 pounds). New Zealand sea lion males have a defined mane around their shoulders and a dark brown or black color. Females are a much lighter grey and some are even yellow with some darker shades around the flippers.

New Zealand sea lions are carnivores (eat meat or animal parts) and also recognized as piscivores (eat fish) and molluscivores (eat mollusks) They store and cache food. They mainly eat arrow squids and also prey on red cods, opalfishes, other small local fishes, octopuses, rays and sharks. Most dives are to less than 200 meters and last for four to five minutes. Immature sea lions feed on the same type and size of prey as adults. When they feed, New Zealand sea lions travel up to 175 kilometers from their resident haul out area. There have been reports of New Zealand sea lions traveling on land and hunting Southern Royal Albatross. A number of studies have concluded that New Zealand sea lions often forage and function to its physiological limits and this limits reproduction.

New Zealand Sea Lion Behavior and Reproduction

New Zealand sea lions are natatorial (equipped for swimming), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), sedentary (remain in the same area), territorial (defend an area within the home range), social (associates with others of its species; forms social groups), and have dominance hierarchies (ranking systems or pecking orders among members of a long-term social group, where dominance status affects access to resources or mates).[Source: David Ferland, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

New Zealand sea lions are not migratory. Tracking of females has shown that they do not travel between the breeding sites in the Auckland Islands and the Campbell Islands. Their only movement is between the beaches under the control of the bulls with whom they breed and the birthing beaches. Male New Zealand sea lions have social hierarchies in which the dominant territorial male has breeding rights leaving juvenile and bachelor males mostly excluded from mating.

New Zealand sea lions are known for being affectionate. Biologist Martin Cawthorn, who studied the seal lions on remote Enderby Island, told National Geographic, "There were no females on shore when I arrived, so I lay down on the grass to observe the males. Soon a lone adult female emerged from the surf, looked around, and headed straight for me. She sniffed along my leg, then snuggled in to the curve of my body and fell asleep. So did I after counting her pulse and breathing rate." [Source: Roger Gentry, National Geographic, April 1987]

New Zealand sea lions communicate with sound and sense using touch, sound and chemicals detected by smelling. Male California sea lions use vocal communication to indicate territorial ownership, sexual readiness, and readiness to fight. Females use vocal cues to communicate alarm and readiness to suckle to their pups. Pups have an alarm vocalization as well as a vocalization to indicate hunger.

New Zealand sea lions are polygynous (males have more than one female as a mate at one time) and engage in seasonal breeding — once every one to two years between December to early January in New Zealand's summer months. Males are territorial. One dominant male occupies a beach in late November and harems of up to 25 females gather around him in December. Other bulls remain on the perimeter of the territory occasionally challenging the dominant male. By late January, the harems break up and bulls disperse. The average gestation period is 11 months. The number of offspring is one. Females reach sexual maturity as early as three years; males do so at eight to nine years.[Source: David Ferland, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Parental care is provided by females, who move to a breeding beach about two days before giving birth. At birth males are larger than females, with males weighing in at about 10.6 kilograms and females 9.7 kilograms. During their first year, the pups are completely dependent on the mother for food and protection. Body reserves for pups are relatively low at birth. Suckling occurs for eight to nine days before the mother's first foraging trip, which tends to last for only two days. A direct influence on pup mortality is male harassment; females move pups to inland vegetation six weeks after birth, presumably to protect them from adult males. New Zealand sea lion pups play around in the forests and cliffs of their home islands while their mothers are out at sea. The pups can recognizes the mooing sound of their mothers, who in turn can recognize the bleating sounds made by their young. Pups are typically brown in appearance with young males resembling females until full maturation. Young become independence around 12 months.

Southern Elephant Seals

Southern elephant seals(Scientific name: Mirounga leonina) are slightly larger, more numerous but less studied than northern elephant seals, the other elephant seal species. The range of these species do not overlap. Male southern elephant seals can live to be 14 years old while females can live to be 20 years old. On average, southern elephant seals live about 9.5 years. There are around 325,000 of them, [Source: Maelan Hauswirth, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Southern elephant seals inhabit large portions of the southern hemisphere. This includes coastal areas and islands of Antarctica and islands south of and the southern tips of Africa, South America, Australia and New Zealand. When foraging for food, Southern elephant seals travel between 40º latitude south and the Antarctica mainland. Southern elephant seals inhabit a large portion of the southern hemisphere, but major breeding populations are only in a handful of places sub-Antarctic islands and in Antarctica. They are also found on the Valdes Peninsula in South America. They spend much of their time in the open seas of the Southern Ocean and the southern Pacific, Atlantic, and Indian oceans. They only come to land when they breed, moult, give birth, and take care of their offspring. When on land, they stay on beaches close to the ocean. Southern elephant seals are typically found in deep water at depths of 200 to 1000 meters (656 to 3280 feet). They feed in deep water and can dive up to 1,000 meters (3,300 feet) deep, even reaching the sea floor in areas. When sometimes rest on ice flows.

See Separate Article: SOUTHERN ELEPHANT SEALS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, MATING ioa.factsanddetails.com

Leopard Seals

Leopard seals (Scientific name: Hydrurga leptonyx) are one of the world’s most dangerous animals. Weighing up to 380 kilograms (840 pounds), they rarely attack humans but they have and killed some. Their lifespan in the wild is estimated to be 26 years, with a high of 30 years. The scientific name of leopard seals, Hydrurga leptonyx, literally translated means 'slender-clawed water-worker'. Their common name comes from their patterned skin.[Source: Taiyler Simone Mitchell, Business Insider December 24, 2022]

Leopard seals are apex predators at the top of the Antarctic food chain. Their only known natural predators are killer whales, however leopard seals are rarely eaten. Leopard seals themselves are notorious predators who feed on penguins, fish, squid, krill and other seals, mostly crabeater seal and fur seal pups. They are the only seals that to regularly hunt warm-blooded prey and kill other mammals and seals. Despite their reputation as fearsome predators, leopard seals feed primarily on krill, using their lobodont teeth to filter these small crustaceans from the water. They also eat fish and squid. [Source:Paul Nicklen, Kim. Heacox, National Geographic, November 2006]

Leopard Seals are found throughout the Antarctic and nearby islands and have been seen as far north as Australia, South America and South Africa. They reside mostly on and around the ice packs but are occasionally seen on Antarctic beaches and subantarctic islands if there is enough ice substrate nearby. These seals roam a huge area. Little is known about their biology and even their numbers. Estimates range from 200,000 to 400,000. Because they eat whatever is available scientists track their diets to get a sense of the available food supply in an area. By chemically analyzing their whiskers, scientists can determine roughly three years of feeding patterns.

See Separate Article: LEOPARD SEALS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND PENGUINS ioa.factsanddetails.com

Crabeater Seals

Crabeater seals(Lobodon carcinophaga) are also known as krill-eater seals. True seals with a circumpolar distribution around the coast of Antarctica, they are the only member of the genus Lobodon and are occasionally sighted on the extreme southern coasts of Argentina, South Africa, Australia and New Zealand. They spend the entire year in the pack ice zone as it advances and retreats seasonally, primarily staying within the continental shelf area in waters less than 600 meters (2,000 feet) deep. [Source: Wikipedia]

Crabeater seals are medium to large in size (over 2 meters, 6.6 feet in length), relatively slender and pale-colored.They are far and away the most abundant seal species in the world. Population estimates are very sketchy but it has been determined that there are at least 7 million of them and possibly as many as 75 million. This success of this species is due to their specialized predation on the abundant Antarctic krill of the Southern Ocean, for which it has uniquely adapted, sieve-like tooth structure. Their scientific name means "lobe-toothed (lobodon) crab eater (carcinophaga)" — a reference to their finely lobed teeth adapted to filtering krill.

In spite of their name, crabeater seals do not eat crabs. Especially young are an important food source for leopard seals. Crabeater seals share a common recent ancestor with the other Antarctic seals such as leopard seals, Ross seals and Weddell seals. These species, collectively belonging to the Lobodontini tribe of seals, share teeth adaptations including lobes and cusps useful for straining smaller prey items out of the water column. The large population of crabeater seals is claimed to be a threat to large baleen whales as they both eat krill and crabeater seals .

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, New Zealand government

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org , National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New Zealand Geographic, New Zealand Tourism, New Zealand Herald, Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various books, websites and other publications

Last updated September 2025