Home | Category: Nature, Environment, Animals

MOA SPECIES

From "The evolutionary history of the extinct ratite moa and New Zealand Neogene paleogeography" PNAS

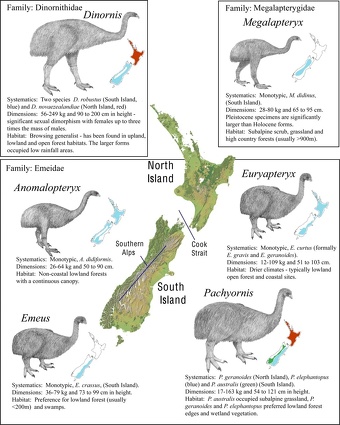

There are nine recognized species of moa, all of which are extinct flightless birds endemic to New Zealand. These birds belonged to the ratite group and included the massive North Island giant moa and South Island giant moa (genus Dinornis), the tallest and heaviest species, as well as smaller birds like the Bush Moa (genus Anomalopteryx) and the Upland Moa (genus Megalapteryx).

The nine recognized species of moa, grouped by their genus:

Anomalopteryx (Bush Moa or Lesser Moa)

1) Bush Moa (Anomalopteryx didiformis)

Dinornis (Giant Moa)

2) North Island Giant Moa (Dinornis novaezealandiae)

3) South Island Giant Moa (Dinornis robustus)

Emeus (Eastern Moa)

4) Eastern Moa (Emeus crassus)

Euryapteryx (Stout-legged Moa)

5) Stout-legged Moa (Euryapteryx curtus)

Megalapteryx (Upland Moa)

6) Upland Moa (Megalapteryx didinus)

Pachyornis (Heavy-footed Moa)

7) Crested Moa (Pachyornis australis)

8) Heavy-footed Moa (Pachyornis elephantopus)

9) Mantell's Moa (Pachyornis geranoides)

Before 11 species were recognized but recent studies using ancient DNA recovered from bones in museum collections suggest that distinct lineages exist within some of these. One factor that has caused much confusion in moa taxonomy is the intraspecific variation of bone sizes, between glacial and interglacial periods.

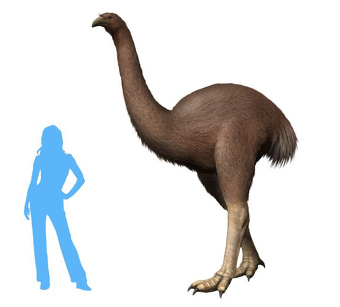

The largest moas were about 3.6 meters (13 feet) tall with their neck outstretched and weighed and about 230 kilograms (510 pounds). The smallest were about the size of a turkey. Medium size moas stood about 1.2 meters (four feet) tall, about the size of a rhea or cassowary. Several species were short and turkey- like. It was once thought that there were three large species but now scientists believe there were only two — one of the North Island and the other on the South Island. After extracting DNA samples from moa fossils it was determined that bones thought to be from different species because their sizes were so different were in fact from the same species in which the females were really big and the males were much smaller. In some cases females were two and half times heavier and 50 percent taller than males of the same species. In most animal species, usually it is the males that are bigger. The smallest species tended to live in high moorlands. The smaller species had hair-like feathers that extended past their legs to their feet. [Source: New York Times]

RELATED ARTICLES:

MOAS: HISTORY, CHARACTERISTICS, REPRODUCTION, EXTINCTION, DE-EXTINCTION? ioa.factsanddetails.com

EMUS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

EMUS AND HUMANS: MEAT, OIL, RANCHING AND WARS ioa.factsanddetails.com

CASSOWARIES: HISTORY, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

CASSOWARIES AND HUMANS: HISTORY, SIDE BY SIDE, ATTACKS ioa.factsanddetails.com

SOUTHERN CASSOWARIES: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

CASSOWARIES OF NEW GUINEA: SPECIES, WHERE THEY LIVE, WHAT THEY'RE LIKE ioa.factsanddetails.com

KIWIS: EVOLUTION, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

KIWI SPECIES: NORTHERN, SOUTHERN, SPOTTED, LARGEST, SMALLEST ioa.factsanddetails.com

SOUTHERN BROWN KIWI: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

KIWIS, HUMANS AND CONSERVATION ioa.factsanddetails.com

KEAS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, PLAYFULNESS, INTELLIGENCE, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

KAKAPO: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION, SAVING THEM FROM EXTINCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

KOKAKOS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

BIRDS OF NEW ZEALAND: SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

Distribution of North and South Island Moa Species

Moa genuses:

Top row (right to left): 1) Anomalopteryx (Bush Moa or Lesser Moa); 2) Pachyornis (Heavy-footed Moa)

Middle row (right to left): 1) Euryapteryx (Stout-legged Moa); 2) Megalapteryx (Upland Moa)

Bottom: Dinornis (Giant Moa)

The moas found in the high-rainfall west coast beech (Nothofagus) forests of the South Island of New Zealand were bush moas (Anomalopteryx didiformis) and South Island giant moas (Dinornis robustus). Those residing in the the dry rainshadow forests and shrublands east of the Southern Alps included heavy-footed moas (Pachyornis elephantopus), stout-legged moas (Euryapteryx curtus), eastern moas (Emeus crassus) and South Island giant moas. [Source: Wikipedia]

“Subalpine moas” of the South Island may have included widespread South Island giant moas and the two other moa species that existed in the South Island: 1) Crested Moa (Pachyornis australis) was the rarest moa species and the only moa species so far not discovered in Māori middens. Its bones have been found in caves in the northwest Nelson and Karamea districts (such as Honeycomb Hill Cave), and some sites around the Wānaka district. 2) Upland Moas (Megalapteryx didinus) were more widespread and their common name is connected with their bones being commonly found in subalpine areas. However, they also occurred down to sea level in areas with steep and rocky terrain (such as Punakaiki on the west coast and Central Otago). The were present in at least in several coastal locations such as on Kaikōura, Otago Peninsula, and Karitane.

Significantly less is known about the North Island moas than the South Island ones due to the scarcity of fossil sites, but the basic pattern of moa-habitat relationships was the same. The South Island and the North Island shared some moa species — stout-legged moas (Euryapteryx curtus), (Euryapteryx curtus and bush moas (Anomalopteryx didiformis) — but most were exclusive to one island, reflecting divergence over several thousand years since lower sea level in the Ice Age had made a land bridge across the Cook Strait.

In the North Island, North Island giant moas (Dinornis novaezealandiae) and bush moas (Anomalopteryx didiformis) dominated the high-rainfall forest habitat, a similar pattern to the South Island. The other moa species present in the North Island — stout-legged moas (Euryapteryx curtus) and Mantell's moas (Pachyornis geranoides) — tended to inhabit drier forest and shrubland habitats. Mantell's moas occurred throughout the North Island.

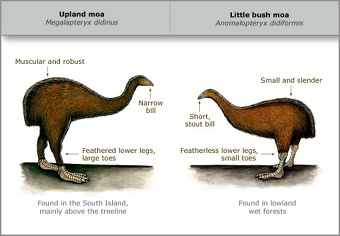

Small Moa Species

Bush moas (Anomalopteryx didiformis) are also known as little bush moas and lesser moa. Members of lesser moa (Emeidae) family, they were one of the smallest moa species and lived in dense lowland conifer forests, broad-leafed southern beech forests and scrubland. They relatively slender were and at 1.3 meters (4.2 feet) were slightly taller than a turkey and is estimated to have weighed around 30 kilograms (66 pounds).

Bush moas were fairly common. They inhabited much of New Zealand's North Island and some small sections of the South Island. They possessed a sturdy, sharp-edged beak, suggesting that their diet was made up of twigs and other tough plant material. Bush moa coprolites (fossilized feces) indicates that ferns were a crucial food source for them.[8]

Mantell's moas (Pachyornis geranoides) are also known as Mappin's moas or moa ruarangi. A relatively small moa, they inhabited lowland environments like shrublands, grasslands, dunelands, and forests on the North Island of New Zealand. Their name honors New Zealand naturalist and politician Walter Mantell. Mantell’s moas ranged in weight from 17 to 36 kilograms (37 to 79 pounds) and were about a a half a meter to a meters (1.7 to 3.3 feet) tall. The bill of heavy-footed moas closely resembled that of Mantell’s moas and features a deeply grooved and pointed mandible (lower jaw bone) and it is assumed the diet of the two species was similar. [Source: Keenan Bailey, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Crested moas weighed around 75 kilograms (165 pounds). They were endemic to the South Island of New Zealand, where they occupied the high altitude sub-alpine forests in the North West, particularly in the Nelson area. Crested moa remains have been found in the Honeycomb Hills Cave and other caves there. Their robust beak with a pointed tip, sturdy jaws, together with large numbers of gizzard stones suggests the diet of crested moas was high in fibrous plant material and included branches of trees and shrubs.

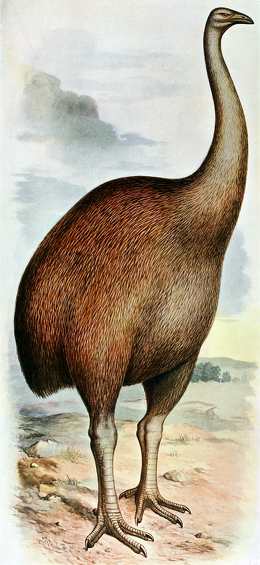

Giant Moas

There were two species of Giant Moa (Dinornis); 1) North Island Giant Moa (Dinornis novaezealandiae) and 2) South Island Giant Moa (Dinornis robustus). Giant moas were taller and bigger than other moas as their name suggests. They also had thinner leg bones than other moas, indicating that they were agile, though they likely moved slowly and cautiously. Giant moas were the only large ratites that sported a hallux (the first digit of the foot). The growth and development of their long bones has been found to be much slower compared to that of other ratites such as ostriches.[Source: Wikipedia]

Giant moas were likely fully feathered, except for their heads and a small portion of the neck, as well as the tarsus and feet. Although they were very tall birds they mostly held their necks horizontally rather than vertically. Giant moas most likely were long-lived birds which took some time to reach full maturity and attain their large size. If giant moas behaved similarly to cassowaries, females likely would have competed for males, as they were much larger, and males would have incubated the eggs and primarily reared the chicks, as females would have been too heavy to incubate the thin-shelled eggs. However, their method of incubation is still unknown. They nested in rock shelters from late spring to early summer. Chicks are speculated to have been striped, like those of other ratites.

It has been said that giant moas were the ecological equivalent of giraffes and even long-necked plant-eating sauropod dinosaurs. Giant moas had a very robust bill, and finds of a relatively large collection of gizzard stone for grinding food indicate a highly fibrous diet. In addition to their bills, moas had stronger neck muscles than other ratite families, which might have given them a stronger pulling, tugging force. They also could have used their necks to reach higher vegetation, if necessary.

South Island Giant Moas

South Island giant moas (Dinornis robustus) were the largest species of moa. Known in Māori by the name moa nunui, they were one of the tallest-known bird species ever known, exceeded in weight only by the heavier but shorter extinct elephant bird of Madagascar. Adult female South Island giant moas were two meters (6.6 feet) tall at the back, and could reach foliage up to 3.6 meters (11.9 feet) off the ground, making them the tallest bird species known. They weighed 200 kilograms (440 pounds) on average, and females may have weighed more than 250 kilograms (550 pounds). Elephant birds weighed more. Only one egg positively assigned to the South Island giant moa has been found — around Kaikōura. This egg — measuring 2.4 centimeters (9.4 inches) in length and 17.8 centimeters (7 inches) in width — was the largest moa egg found in museum collections as of 2006.

South Island giant moas had very large bodies and proportionately small heads — a trait common with all ratites. Analysis of their skull suggests they had somewhat poor eyesight due to their small orbits, rounded bills, and appear to to have had a strongly-developed olfactory system and thus a good sense of smell. Feathers belonging to this species have been found, revealing that its plumage was plain brown or slightly streaked.

Most foraging by South Island giant moas took place in forests or open fields. Their coprolites (fossilized feces) revealed that their diet included twigs, seeds, berries, leaves, flowers, vines, herbs, and shrubs. It is likely that South Island giant moas fed on vegetation that other moas were unable to be digest, and thereby avoided competition with other grazers. Their bill would have allowed them to feed by means of cutting and breaking twigs and stems via lateral shaking.

South Island giant moas lived on the South Island of New Zealand as well as in Rakiura and Native Island. Their habitat appears to have mainly been in lowlands — in shrubland, duneland, grassland, and forests. Along with other moa species, South Island giant moas went extinct due to predation from humans in the 15th century, about 200 years after colonisation by the Māori.

North Island Giant Moas

North Island giant moas (Dinornis novaezealandiae) are considered to be a tad smaller than South Island giant moas. Known in Māori as kuranui, North Island giant moas exhibited strong sexual dimorphism, with males weighing between 55 and 88 kilograms (121 to 194 pounds) and females between 78 and 249 kilograms (172 and 549 pounds), with the weights determined using algorithms derived from data in the bones of juvenile Dinornis. They are believed to have been able to stretch their necks so their heads reached a height of about 3 meters (10 feet) compared to 3.6 meters (11.9 feet) for South Island giant moas.

North Island giant moas inhabited the North Island of New Zealand, living in lowland habitats such as shrublands, grasslands and forests. They have been described as being “two-legged, tailless, wingless” and “clad in woolly fibres”. They had had “long, shaggy, hair-like feathers up to 18 centimeters long”. Preserved feathers and skin fragments indicate that all but the legs were fully feathered. Their feathers were brown, sometimes with pale edging. Even though North Island giant moas was largely hunted for consumption by Maori findings have also shown that their bones were used to make many one-piece fish-hooks.

There is some evidence that the Kahikatea-Pukatea-tawa forest, Waikato, was home to the largest concentration of the North Island giant moas. Bone discoveries also reveal that they also inhabited nearby areas, such as Opito, Auckland. North Island giant moas are believed to have had a diet and consumed a wide range of plants similar that of South Island giant moas like beech, seeds and leaves of small shrubs in forest areas. Tracks of North Island giant moas have been found in the Poukawa region that lead to freshwater springs and the bottom of rocky cliffs, where the massive birds might have nested and rested.

Whole moa eggs are rare, however there is an of abundance of fragment. These suggest that eggs of North Island giant moas weighed over 3 kilograms (6.6 pounds) and measured roughly 19 by 15 centimeters (8 by 6 inches). One intact egg — measuring 19.7 x 15.1 centimeters — mm) attributed to this species was found in a a rock shelter in the Mangawhitikau Valley near Waitomo. Analysis of ancient DNA from surfaces of the outer shell of eggs found only male North Island giant moa DNA, suggested that males likely incubated the eggs. Findings from another site reveal female DNA on the inside and outside of egg shells thought to be from the egg laying process. Even though male North Island giant moas were significantly lighter than females, they were still heavy birds and questions have been raised as to how they could have incubated eggs without breaking them. It therefor seems unlikely that larger moas would have been able to incubate their eggs using the same contact method that is practiced by almost all extant birds. It has been speculated that maybe they formed a special nest that would support their body weight in some way.

Heavy-Footed Moas

Heavy-footed moas (Pachyornis elephantopus) were members of the lesser moa family. Widespread across the South Island of New Zealand, they inhabited lowland environments like shrublands, dunelands, grasslands, and forests. Heavy-footed moas were about 1.8 meters (5.9 feet) tall, and weighed as much as 145 kilograms (320 pounds).Three complete or partially complete moa eggs in museum collections are considered eggs of the heavy-footed moa, all from Otago. These eggs have an average length of 22.6 centimeters (8.9 inches) and a width of 15.8 centimeters (6.2 inches), making these the second-largest moa eggs after those of South Island giant moas egg specimen.

Heavy-footed moas are thought to have been less common than other moa species. Their fossils and bones are much rarer than those of other moas. Heavy-footed moas were found only on the South Island of New Zealand, mostly on the eastern side of the island, with northern and southern variants. were absent from sub-alpine and mountain habitats, the home of crested moas (Pachyornis australis).

Heavy-footed moas are named for their particularly large and robust feet, which helped them consume tough vegetation and bulldoze through dense shrubland in their preferred dry and shrubby habitat. “Elephantopus” in their scientific name, means "elephant foot". Heavy-footed moas had differently shaped heads and beaks compared to other moa species, suggesting they had a different diet. In 2007, Jamie Wood described the gizzard contents of a heavy-footed moa for the first time. He found evidence of 21 plant species which included Hebe leaves, various seeds and mosses as well as a large amount of twigs and wood, with some of the pieces being of considerable size.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org , National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New Zealand Geographic, New Zealand Tourism, New Zealand Herald, Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various books, websites and other publications

Last updated September 2025